Convcultcoursetext.8.23.09 Jp Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monsters & Miscellanea

Monsters & Miscellanea Volume 1-02: Skeletons by Barry Dore https://www.dmsguild.com/browse.php?author=Barry_Dore Title Art: Magz Wiseman https://www.yellowphonebox.com Cover Image: DMs Guild Creator Resource 3. Flesh Stealer Flesh Stealer, Undeath Dog 4. Skeletal Priests Skeletal Priest, Skeletal Priest of Orcus 5. Skeletons Skeleton: Crocodile, Giant Rat, Hill Giant, Wolf 6. Skeletons, Energy-Infused Cold-Infused; Skeleton, Mammoth Skeleton 7. Fire-Infused; Skeleton, Mastiff Skeleton 8. Lightning-Infused; Skeleton, Velociraptor Skeleton 9. Skeletons, Mold-Infested Mold-Infested; Skeleton, Hook Horror Skeleton 10. Bard Bard College: College of Bones 11. Magic Items Potions, Shodrom's Armaments DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, Ravenloft, Eberron, the dragon ampersand, Ravnica and all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. This work contains material that is copyright Wizards of the Coast and/or other authors. Such material is used with permission under the Community Content Agreement for Dungeon Masters Guild. All other original material in this Samplework is copyright 2019 by Barry Dore and file published under the Community Content Agreement for Dungeon Masters Guild. Not for resale. Permission granted to print or photocopy this document for personal use only. Monsters & Miscellanea 1-02 2 Flesh Stealer Undeath Dog This foul variant of the flesh stealer takes the form of a The flesh stealer appears at first glance to be a typical death dog's two-headed skeleton, empowered with a life humanoid skeleton, but it is far from the norm. -

Rachel Barton Violin Patrick Sinozich, Piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 041 INSTRUMENT of the DEVIL 1 Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op

Cedille Records CDR 90000 041 Rachel Barton violin Patrick Sinozich, piano DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 041 INSTRUMENT OF THE DEVIL 1 Saint-Saëns: Danse Macabre, Op. 40 (7:07) Tartini: Sonata in G minor, “The Devil’s Trill”* (15:57) 2 I. Larghetto Affectuoso (5:16) 3 II. Tempo guisto della Scuola Tartinista (5:12) 4 III. Sogni dellautore: Andante (5:25) 5 Liszt/Milstein: Mephisto Waltz (7:21) 6 Bazzini: Round of the Goblins, Op. 25 (5:05) 7 Berlioz/Barton-Sinozich: Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath from Symphonie Fantastique, Op. 14 (10:51) 8 De Falla/Kochanski: Dance of Terror from El Amor Brujo (2:11) 9 Ernst: Grand Caprice on Schubert’s Der Erlkönig, Op. 26 (4:11) 10 Paganini: The Witches, Op. 8 (10:02) 1 1 Stravinsky: The Devil’s Dance from L’Histoire du Soldat (trio version)** (1:21) 12 Sarasate: Faust Fantasy (13:30) Rachel Barton, violin Patrick Sinozich, piano *David Schrader, harpsichord; John Mark Rozendaal, cello **with John Bruce Yeh, clarinet TT: (78:30) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foun- dation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by grants from the WPWR-TV Chan- nel 50 Foundation and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. Zig and zig and zig, Death in cadence Knocking on a tomb with his heel, Death at midnight plays a dance tune Zig and zig and zig, on his violin. -

Original Paper Leonardo's Skull and the Complex Symbolism Of

Journal of Research in Philosophy and History Vo l . 4, No. 1, 2021 www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/jrph ISSN 2576-2451 (Print) ISSN 2576-2435 (Online) Original Paper Leonardo’s Skull and the Complex Symbolism of Holbein’s “Ambassadors” Christopher W. Tyler, Ph.D., D.Sc.1 1 San Francisco, CA, USA Received: January 31, 2021 Accepted: February 10, 2021 Online Published: February 19, 2021 doi:10.22158/jrph.v4n1p36 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.22158/jrph.v4n1p36 Abstract The depiction of memento mori such as skulls was a niche artistic trend symbolizing the contemplation of mortality that can be traced back to the privations of the Black Death in the 1340s, but became popular in the mid-16th century. Nevertheless, the anamorphism of the floating skull in Hans Holbein’s ‘The Ambassadors’ of 1533, though much discussed as a clandestine wedding commemoration, has never been satisfactorily explained in its historical context as a diplomatic gift to the French ambassadors to the court of Henry VIII who were in the process of negotiations with the Pope for his divorce. Consideration of Holbein’s youthful trips to Italy and France suggest that he may have been substantially influenced by exposure to Leonardo da Vinci’s works, and that the skull may have been an explicit reference to Leonardo’s anamorphic demonstrations for the French court at Amboise, and hence a homage to the cultural interests of the French ambassadors of the notable Dinteville family for whom the painting was destined. This hypothesis is supported by iconographic analysis of works by Holbein and Leonardo’s followers in the School of Fontainebleau in combination with literary references to its implicit symbolism. -

Abstract Rereading Female Bodies in Little Snow-White

ABSTRACT REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISIBILITY By Dianne Graf In this thesis, the circumstances and events that motivate the Queen to murder Snow-White are reexamined. Instead of confirming the Queen as wicked, she becomes the protagonist. The Queen’s actions reveal her intent to protect her physical autonomy in a patriarchal controlled society, as well as attempting to prevent patriarchy from using Snow-White as their reproductive property. REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISffiILITY by Dianne Graf A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts-English at The University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Oshkosh WI 54901-8621 December 2008 INTERIM PROVOST AND VICE CHANCELLOR t:::;:;:::.'-H.~"""-"k.. Ad visor t 1.. - )' - i Date Approved Date Approved CCLs~ Member FORMAT APPROVAL 1~-05~ Date Approved ~~ I • ~&1L Member Date Approved _ ......1 .1::>.2,-·_5,",--' ...L.O.LJ?~__ Date Approved To Amanda Dianne Graf, my daughter. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Dr. Loren PQ Baybrook, Dr. Karl Boehler, Dr. Christine Roth, Dr. Alan Lareau, and Amelia Winslow Crane for your interest and support in my quest to explore and challenge the fairy tale world. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER I – BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE LITERARY FAIRY TALE AND THE TRADITIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE FEMALE CHARACTERS………………..………………………. 3 CHAPTER II – THE QUEEN STEP/MOTHER………………………………….. 19 CHAPTER III – THE OLD PEDDLER WOMAN…………..…………………… 34 CHAPTER IV – SNOW-WHITE…………………………………………….…… 41 CHAPTER V – THE QUEEN’S LAST DANCE…………………………....….... 60 CHAPTER VI – CONCLUSION……………………………………………..…… 67 WORKS CONSULTED………..…………………………….………………..…… 70 iv 1 INTRODUCTION In this thesis, the design, framing, and behaviors of female bodies in Little Snow- White, as recorded by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm will be analyzed. -

Dragon Magazine #158

S PECIAL ATTRACTIONS Issue #158 Vol. XV, No. 1 9 Weve waited for you: DRAGONS! June 1990 A collection of lore about our most favorite monster. The Mightiest of Dragons George Ziets Publisher 10 In the D&D® game, no one fools with the dragon rulers and lives for James M. Ward long. Editor A Spell of Conversation Ed Friedlander Roger E. Moore 18 If youd rather talk with a dragon than fight it, use this spell. The Dragons Bestiary The readers Fiction editor Barbara G. Young 20 The gorynych (very gory) and the (uncommon) common dragonet. Thats Not in the Monstrous Compendium! Aaron McGruder Assistant editor 24 Remember those neutral dragons with gemstone names? Theyre 2nd Dale A. Donovan Edition now! Art director Larry W. Smith O THER FEATURES Production staff The Game Wizards James M. Ward Gaye OKeefe Angelika Lokotz 8 Should we ban the demon? The readers respondand how! Subscriptions Also Known As... the Orc Ethan Ham Janet L. Winters 30 Renaming a monster has more of an effect than you think. U.S. advertising The Rules of the Game Thomas M. Kane Sheila Gailloreto Tammy Volp 36 If you really want more gamers, then create them! The Voyage of the Princess Ark Bruce A. Heard U.K. correspondent 41 Sometimes its better not to know what you are eating. and U.K. advertising Sue Lilley A Role-players Best Friend Michael J. DAlfonsi 45 Give your computer the job of assistant Dungeon Master. The Role of Computers Hartley, Patricia and Kirk Lesser 47 The world of warfare, from the past to the future. -

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage Phoebe S. Spinrad Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright© 1987 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. A shorter version of chapter 4 appeared, along with part of chapter 2, as "The Last Temptation of Everyman, in Philological Quarterly 64 (1985): 185-94. Chapter 8 originally appeared as "Measure for Measure and the Art of Not Dying," in Texas Studies in Literature and Language 26 (1984): 74-93. Parts of Chapter 9 are adapted from m y "Coping with Uncertainty in The Duchess of Malfi," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 6 (1980): 47-63. A shorter version of chapter 10 appeared as "Memento Mockery: Some Skulls on the Renaissance Stage," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 10 (1984): 1-11. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spinrad, Phoebe S. The summons of death on the medieval and Renaissance English stage. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. English drama—Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500-1700—History and criticism. 2. English drama— To 1500—History and criticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Death- History. I. Title. PR658.D4S64 1987 822'.009'354 87-5487 ISBN 0-8142-0443-0 To Karl Snyder and Marjorie Lewis without who m none of this would have been Contents Preface ix I Death Takes a Grisly Shape Medieval and Renaissance Iconography 1 II Answering the Summon s The Art of Dying 27 III Death Takes to the Stage The Mystery Cycles and Early Moralities 50 IV Death -

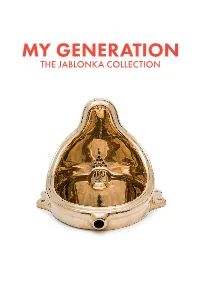

My Generation the Jablonka Collection

MY GENERATION THE JABLONKA COLLECTION Exhibition Facts Duration 2 October 2020 – 21 February 2021 Venue Bastion Hall & Colonade Hall Curators Rafael Jablonka Elsy Lahner, ALBERTINA Works ca. 110 Catalogue Available for EUR 32.90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Wednesdays & Fridays 10 am – 9pm Press contact Fiona Sara Schmidt T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] My Generation The Jablonka Collection 2 October 2020 – 21. February 2021 With this exhibition, the Albertina Museum presents the most recent addition to its holdings: the collection of Rafael and Teresa Jablonka, which, comprising more than 400 works, ranks among the most distinguished collections of American and German art of the 1980s. Rafael Jablonka was born in Poland in 1952. After moving to Germany and taking the detour of working as an exhibition curator, he subsequently founded Galerie Jablonka with venues in Cologne, Berlin, and Zurich, eventually turning from a renowned art dealer into an important and passionate collector. Featuring, among others, Francesco Clemente, Roni Horn, Mike Kelley, Sherrie Levine, and Andreas Slominski, the Jablonka Collection includes artists with whom Rafael Jablonka has worked over the years, whom he promoted, and some of whom he discovered. However, he also collected works by artists beyond the program of his gallery—artists he greatly admired and whose works he ultimately wished to conserve for posterity. -

Performance Research Tissue to Text: Ars Moriendi and the Theatre

This article was downloaded by: [Swansea Metropolitan University] On: 10 May 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 917209572] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Performance Research Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t716100720 Tissue to Text: Ars moriendi and the theatre of anatomy Karen Ingham Online publication date: 06 May 2010 To cite this Article Ingham, Karen(2010) 'Tissue to Text: Ars moriendi and the theatre of anatomy', Performance Research, 15: 1, 48 — 57 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/13528165.2010.485763 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2010.485763 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Graduate Recital Final Draft

Oh the Horror of Song! Louis Tiemann, baritone Sung-Soo Cho, piano Bard Conservatory of Music Sunday, May 9th 2021, 3pm Graduate Degree Recital Murderous Bookends The Peculiar Case of Dr. H.H. Holmes (2010) Libby Larsen (b.1950) I. I state my case II. As a young man III. I build my business (a polka) IV. Thirteen ladies and three who got away (grand waltz macabre) V. Evidence Requiescat A Kingdom by the Sea (1901) Arthur Somervell (1863-1937) The clock of the years Gerald Finzi (1901-1956) from Earth and Air and Rain (1936) The choirmaster’s burial Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) from Winter Words (1956) short 10min pause Die Volksgeschichten Waldesgespräch Robert Schumann (1810-1856) from Liederkreis, Op. 39 (1840) Der Feuerreiter Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) from Mörikelieder (1888) Der Erlkönig Carl Loewe (1796-1869) from Drei Balladen (1817) Der Doppelgänger Franz Schubert (1797-1828) from Schwanengesang (1828) Horreur La vague et la cloche (1871) Henri Duparc (1848-1933) Danse macabre (1872) Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Murderous Bookends After Hearing a Waltz by Bartók (2013) Zachary Wadsworth (b.1983) Oh the Horror of Song! When I was a child, I was deeply afraid of the dark. So much so that I refused to sleep in my own room, opting instead to sleep in the living room, always with a light or the TV on. One day during my undergraduate studies I decided that I was going to overcome my fears. One night, when I was alone in my dorm, I turned off all of the lights, ordered a pizza, and put on the scariest movie I could think of at that time: The Evil Dead. -

Modern Teachers of Ars Moriendi

religions Article Modern Teachers of Ars moriendi Agnieszka Janiak 1 and Marcin Gierczyk 2,* 1 Department of Media and Communication, University of Lower Silesia, 53-611 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Social Sciences, Institute of Pedagogy, University of Silesia in Katowice, 40-007 Katowice, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: It is evident that a change is happening, a breakthrough, in perceptions of death; the next episode is being unveiled. After the stages Philippe Aries named death of the tame and then death of the wild, people today are finally experiencing the humanizing of death, which we call sharing death, whose influence is worth deep analysis. Our hypothesis is that today, Ars moriendi, meeting the needs of the dying, may be learned from the so-called death teachers, whose message is growing noticeably in society. This research shows a certain reversal of social roles that are worth noting and accepting. In the past, a priest was a guide and a teacher in the face of dying and death; today, he has the opportunity to learn Ars moriendi from contemporary teachers of dying, to imagine an empty chair standing by a dying person. Keywords: priest; Ars moriendi; sharing death; death teacher 1. Introduction One of religion’s fundamental functions is the existential one. Each religious system Citation: Janiak, Agnieszka, and facilitates facing existential dilemmas and provides tools to deal with the most incompre- Marcin Gierczyk. 2021. Modern Teachers of Ars moriendi. Religions 12: hensible and tragic aspects of human existence. J.M. Yinger, the American psychologist of 695. -

Midrashic Commentaries on the Phantasmagoria That Is History

Tide and Time: Midrashic Commentaries on the Phantasmagoria that is History Norman Simms Introduction A midrashic story is not conceived as something that exists outside of the text; rather, it is continuous with it. Midrash implies the failure of the sources from which it comes to evoke a final answer, As metonymy, rather than metaphor—extension rather than representation—midrash reveals the gaps it seeks to fill and extends the primary text in which they exist. It reminds us of the voids that precede it.1 What Nietzsche saw as a barbaric tide of cultural erasure, Wagner saw as a tide of cultural renewal.2 The phantasmagoria, an elaborated magic lantern show developed in the final years of the eighteenth century, quickly became a metaphorical model for insights into human character, psychology and social relationship at the same time. It drew deeply from folklore and popular entertainments and helped to shape the genres to come in an industrial age. By projecting old- fashioned imagery of Monarchy, Church and Science, emotions suppressed by the French Revolution of 1789 as superstition and rural stupidity, re- emerged under controlled conditions, forming moments of entertainment, since audiences understood this was an artful illusion. The spectacle—with music, flashing lights, shuddering furniture and eerie speeches—was able to present the mind as something more and other than merely a bourgeois field of conscious activities. The once familiar fears and desires now felt as uncanny phantoms themselves could be assigned to mechanical tricks and, at the same, experienced as originating in the dark recesses of self. -

Developing an Ars Moriendi (The Art of Dying) for the 21 Century

Developing an Ars Moriendi (The Art of Dying) for the 21st Century Study Leave Project for the Kaimai Presbytery August to September 2018 By Rev Donald Hegan Dedication Dedicated to the memory of a dear friend and mentor Pastor Jim Hurn. What sweet fellowship I enjoyed with you and your lovey wife Kaye in your dying days. Jim was determined to commit his dying days into the hands of a living and loving God. He trusted that God would take him on his last great journey. For Jim death was not the opposite of life but just the anaesthetic that God used to change his body. Please be there to greet me at those “Pearly Gates” my dear friend. Rest in Peace. Index I. Introduction page 1-2 1.Let us speak of Death pages 3-9 2.Current Attitudes towards Death pages 10-21 3.Portraits of a Good Death from Scripture and History pages 22-37 4.Developing a Healthy View of Death/ Memento Mori pages 38-42 5.The Churches Traditional Response to Death and Dying pages 43-51 6.Current Societal Trends in Death and Dying pages 52-64 II. Adieu page 65 III. Appendices 1. Short Stories page 66-68 2. Web Resources Worthy of Note page 69 3. Last Rites pages 70-71 4. Printed Resources -Christian Reflection, A series in Faith and Ethics, Study Guides for Death pages 72-93 -My Future Care Plan pages 94-103 IV. Bibliography pages 104-108 Introduction My first encounter with death was when I was eight years old.