University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy the Poetics Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Badminton

Facts and Records History of Badminton In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort held a lawn party at his country house in the village of Badminton, Gloucestershire. A game of Poona was played on that day and became popular among British society’s elite. The new party sport became known as “the Badminton game”. In 1877, the Bath Badminton Club was formed and developed the first official set of rules. The Badminton Association was formed at a meeting in Southsea on 13th September 1893. It was the first National Association in the world and framed the rules for the Association and for the game. The popularity of the sport increased rapidly with 300 clubs being introduced by the 1920’s. Rising to 9,000 shortly after World War Π. The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was formed in 1934 with nine founding members: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Holland, Canada, New Zealand and France and as a consequence the Badminton Association became the Badminton Association of England. From nine founding members, the IBF, now called the Badminton World Federation (BWF), has over 160 member countries. The future of Badminton looks bright. Badminton was officially granted Olympic status in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Indonesia was the dominant force in that first Olympic tournament, winning two golds, a silver and a bronze; the country’s first Olympic medals in its history. More than 1.1 billion people watched the 1992 Olympic Badminton competition on television. Eight years later, and more than a century after introducing Badminton to the world, Britain claimed their first medal in the Olympics when Simon Archer and Jo Goode achieved Mixed Doubles Bronze in Sydney. -

The Grave (Illuminated Manuscript with the Original Illustrations of William Blake to Robert Blair's the Grave) Online

EQTfi [Download pdf ebook] The Grave (Illuminated Manuscript with the Original Illustrations of William Blake to Robert Blair's The Grave) Online [EQTfi.ebook] The Grave (Illuminated Manuscript with the Original Illustrations of William Blake to Robert Blair's The Grave) Pdf Free William Blake audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2095897 in eBooks 2013-07-10 2013-07-10File Name: B00FMWE2Z0 | File size: 64.Mb William Blake : The Grave (Illuminated Manuscript with the Original Illustrations of William Blake to Robert Blair's The Grave) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Grave (Illuminated Manuscript with the Original Illustrations of William Blake to Robert Blair's The Grave): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. AmaseBy Katherine lawLooking forward to see my LordHope to tell everyone how great God is to me. If you could feel the respect for life.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. No contentBy Will ToledoDoes not contain the actual poem by Blair, only poorly-resized images of Blake's drawings. What's the point? This carefully crafted ebook: "The Grave (Illuminated Manuscript with the Original Illustrations of William Blake to Robert Blair's The Grave)" is formatted for your eReader with a functional and detailed table of contents. Robert Blair (1699 – 1746) was a Scottish poet. Blair published only three poems. One was a commemoration of his father-in-law and another was a translation. His reputation rests entirely on his third work, The Grave (published in 1743), which is a poem written in blank verse on the subject of death and the graveyard. -

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage Phoebe S. Spinrad Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright© 1987 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. A shorter version of chapter 4 appeared, along with part of chapter 2, as "The Last Temptation of Everyman, in Philological Quarterly 64 (1985): 185-94. Chapter 8 originally appeared as "Measure for Measure and the Art of Not Dying," in Texas Studies in Literature and Language 26 (1984): 74-93. Parts of Chapter 9 are adapted from m y "Coping with Uncertainty in The Duchess of Malfi," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 6 (1980): 47-63. A shorter version of chapter 10 appeared as "Memento Mockery: Some Skulls on the Renaissance Stage," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 10 (1984): 1-11. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spinrad, Phoebe S. The summons of death on the medieval and Renaissance English stage. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. English drama—Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500-1700—History and criticism. 2. English drama— To 1500—History and criticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Death- History. I. Title. PR658.D4S64 1987 822'.009'354 87-5487 ISBN 0-8142-0443-0 To Karl Snyder and Marjorie Lewis without who m none of this would have been Contents Preface ix I Death Takes a Grisly Shape Medieval and Renaissance Iconography 1 II Answering the Summon s The Art of Dying 27 III Death Takes to the Stage The Mystery Cycles and Early Moralities 50 IV Death -

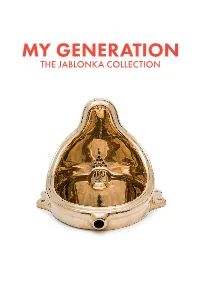

My Generation the Jablonka Collection

MY GENERATION THE JABLONKA COLLECTION Exhibition Facts Duration 2 October 2020 – 21 February 2021 Venue Bastion Hall & Colonade Hall Curators Rafael Jablonka Elsy Lahner, ALBERTINA Works ca. 110 Catalogue Available for EUR 32.90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Wednesdays & Fridays 10 am – 9pm Press contact Fiona Sara Schmidt T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] My Generation The Jablonka Collection 2 October 2020 – 21. February 2021 With this exhibition, the Albertina Museum presents the most recent addition to its holdings: the collection of Rafael and Teresa Jablonka, which, comprising more than 400 works, ranks among the most distinguished collections of American and German art of the 1980s. Rafael Jablonka was born in Poland in 1952. After moving to Germany and taking the detour of working as an exhibition curator, he subsequently founded Galerie Jablonka with venues in Cologne, Berlin, and Zurich, eventually turning from a renowned art dealer into an important and passionate collector. Featuring, among others, Francesco Clemente, Roni Horn, Mike Kelley, Sherrie Levine, and Andreas Slominski, the Jablonka Collection includes artists with whom Rafael Jablonka has worked over the years, whom he promoted, and some of whom he discovered. However, he also collected works by artists beyond the program of his gallery—artists he greatly admired and whose works he ultimately wished to conserve for posterity. -

From Address to Debate: Generic Considerations in the Debate Between Soul and Body

FROM ADDRESS TO DEBATE: GENERIC CONSIDERATIONS IN THE DEBATE BETWEEN SOUL AND BODY by J. Justin Brent Although many scholars think of debate as a distinctively medieval genre,1 just about every culture known to man has composed verbal contests of wit that might be termed debates.2 Their universal appeal results at least in part from two inherent features. One is the excitement and suspense that comes from observing a contest between two skillful opponents. Like spectator sports, verbal contests provide a vicarious pleasure for the audience, which shares the suspense of the contest with the two or more opponents. The second aspect, more frequently dis- cussed by students of medieval debate, is the tendency towards opposi- tion. Because a contest cannot take place without opponents, verbal contests tend to produce philosophical perspectives that are both op- 1Thomas Reed, for instance, claims that debate is “as ‘distinctly medieval’ as a genre can be” (Middle English Debate Poetry [Columbia 1990] 2); and John W. Conlee sug- gests that no other age was more preoccupied with “the interaction of opposites,” which furnishes the generating principle of debates (Middle English Debate Poetry: A Critical Anthology [East Lansing 1991] xi–xii). The medieval poets’ intense fascination or spe- cial fondness for debate poetry often receives mention in studies of this genre. 2As evidence of their existence in some of the earliest writing cultures, scholars have pointed out several debates in ancient Sumerian culture. See S. N. Kramer, The Sumer- ians (Chicago 1963) 265; and H. Van Stiphout, “On the Sumerian Disputation between the Hoe and the Plough,” Aula Orientalis 2 (1984) 239–251. -

MARK HADDON Is the Author of Three Novels, Including the Curious

MARK HADDON is the author of three novels, including The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and The Red House , and a volume of poetry, The Talking Horse and the Sad Girl and the Village Under the Sea . He has written drama for stage, TV and radio. His latest book, a collection of short stories, is The Pier Falls , published by Jonathan Cape. STATES OF MIND: Tracing the Edges of Consciousness is an exhibition developed by Wellcome Collection to interrogate our understanding of the conscious experience. Exploring phenomena such as somnambu- lism, synaesthesia and disorders of memory, the exhibition examines ideas around the nature of consciousness, and in particular what can happen when our typical conscious experience is interrupted, damaged or undermined. WELLCOME COLLECTION is the free visitor destination for the incurably curious. It explores the connections between medicine, life and art in the past, present and future. Wellcome Collection is part of the Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation dedicated to improving health by supporting bright minds in science, the human- ities and social sciences, and public engagement. A collection of literature, science, philosophy and art Introduction by Mark Haddon Edited by Anna Faherty First published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by Wellcome Collection, part of The Wellcome Trust 215 Euston Road London NW1 2BE. Published for the Wellcome Collection exhibition States of Mind: Tracing the Edges of Consciousness, curated by Emily Sargent. www.wellcomecollection.org Wellcome Collection is part of the Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation dedicated to achieving extraordinary improvements in human and animal health. -

Ubi Sunt Dracones? the Inward Evolution of Monstrosity from Monstrous Births to Iain Banks’ the Wasp Factory

Master’s Degree in European, American and Postcolonial Languages and Literatures Final Thesis Ubi Sunt Dracones? The Inward Evolution of Monstrosity from Monstrous Births to Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory Supervisor Ch. Prof. Flavio Gregori Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Shaul Bassi Graduand Martina Nati 857253 Academic Year 2019 / 2020 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter 1 – Monstrous Bodies 12 1.1 Monstrosity and Deformity from the Middle Ages to the 12 Enlightenment 1.2 The Abnormal Body in the 18th and 19th Centuries 36 Chapter 2 – Monstrous Minds 41 2.1 Monstrous Anxiety at the Turn of the 20th Century 41 2.2 The Monster Within 57 2.3 A Contemporary Monster: the Serial Killer 63 Chapter 3 – The Monstrous in Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory 70 3.1 Frank’s Monstrous Body 73 3.2 Frank as a Moral Monster 81 3.3 Frank’s Uncanny Double 88 3.4 Monstrous Beliefs 91 Conclusion 96 Acknowledgements 104 Bibliography 105 “if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you” Friedrich Nietzsche INTRODUCTION There is something fascinating about the aesthetics of monstrosity, which is not always understandable but undeniably universal. It is something dark, twisted and daunting which, nevertheless, lures us into its depths. Monsters scare, petrify and make one feel vulnerable and exposed; yet, they never disappear, they can never truly be annihilated. They lurk in the most obscure corners of one‘s mind, festering, dormant until summoned, and then they emerge from the shadows ready to wreak havoc. They embody terrific possibilities, violation, transgression and liminality: all that is dangerous, yet all that is unavoidable. -

Minutes: Badmintonscotland Board Meeting Conference Call Wednesday 11Th November 2020 at 6:30Pm

Minutes: BADMINTONscotland Board Meeting Conference Call Wednesday 11th November 2020 at 6:30pm Board: David Gilmour Chair Frank Turnbull President Carolyn Young Vice President Keith Russell Chief Executive Morag McCulloch Events Committee Chair Jill O’Neil Engagement Committee Chair Christine Black Performance Committee Chair Gordon Haldane Finance Committee Chair Invited: Keith Farrell Ewen Cameron sportscotland Partnership Manager Colleen Walker Finance Manager, Badminton Scotland Nicky Waterson Head of Engagement, Badminton Scotland Penny Dougray Minute Taker David Gilmour welcomed Ewen Cameron (sportscotland Partnership Manager) to his first Board meeting, with board members introducing themselves thereafter; 1 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies had been received from Ian Campbell. 2 MINUTES OF MEETING HELD ON 16 SEPTEMBER 2020 (previously circulated) The minutes of the meeting held on 16 September 2020 were approved. 3 DECLARATION OF ANY INTEREST Both David Gilmour and Gordon Haldane received payments for coaching services. 4 MATTERS ARISING/OUTSTANDING ITEMS A meeting planned between Keith Russell, David Gilmour, Jill O’Neil and Nicky Waterson (NW) to progress a plan for Equality and Integrity had not taken place: KR would rearrange this. 5 CEO Report Complaints. One complaint had been received regarding the entries made by Badminton Scotland for the 2020 European Juniors Individual event. KR has replied and the matter was concluded from a Badminton Scotland perspective. DG advised that Badminton Scotland had followed robust processes, in what was a challenging time, given lack of tournament results and lack of training opportunities. Staffing. Malou Guldbaek had submitted her notice, following her decision to return to her native Denmark. Her significant contribution over the last 15 months was recognised. -

The Meeting of the Three Living and the Three Dead

THE MEETING OF THE THREE LIVING AND THE THREE DEAD The meeting of the three living and the three dead shows an occasional meeting of three carefree very relevant men (normally three kings or a priest, a nobleman and a member or the upper-middle class) who enjoy life in their adulthood. These three men, apparently not acquainted with pain, go hunting and, on turning a curve or reaching a crossroads marked by a landmark, come up against three dead whose corpses are rotten and eaten by maggots. In some versions the dead ones regain consciousness for a moment to warn the living ones, we once were as you are, as we are so shall you be. However, in others the dead ones lie lifeless inside their coffins and it is a hermit that warns the living ones about the expiry of earthly goods. The living ones, impressed by the vision, change their existential attitude and, from that moment on, look after their souls, afraid of death’s proximity. The topic comes from the Buddhist sapiential literature by which the Prince Siddhartha Gautama had four meetings, one of them with a dead, before becoming Buddha. It must have passed to both the Persian and Abbasid literature through the trading routes and it reached the West deeply transformed, with the main characters tripled to gain dramatic intensity. Keywords: Dead, living, skeletons, hermitage, hermit, hawk, hunter, harnessed horses, noblemen, princes, kings, crossroads, landmark, cemetery, crown. Subject: The meeting of the three living and the three dead is found in French literature and bibliography under the expression: le dit des trois morts et des trois vifs or les trois vivant et trois mortis. -

Danse Macabre in Text and Image in Late- Medieval England Oosterwijk, S

'Fro Paris to Inglond'? The danse macabre in text and image in late- medieval England Oosterwijk, S. Citation Oosterwijk, S. (2009, June 25). 'Fro Paris to Inglond'? The danse macabre in text and image in late-medieval England. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13873 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13873 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER 3 ‘Owte of the frensshe’: John Lydgate and the Dance of Death John Lydgate’s poem The Dance of Death was a translation ‘Owte of the frensshe’, as the author himself stated in his translator’s ‘Envoye’ at the end of the poem, yet ‘Not wordebeworde / but folwyng the substaunce’ (E:665-66) – an ancient topos.1 Even so, Lydgate’s poem was indeed no slavish imitation but an adaptation of a French poem that had been attracting attention since its incorporation in a wall-painting at the cemetery of Les Innocents in Paris not long before Lydgate’s presumed visit in 1426. Despite being an early adaptation of a popular French text, Lydgate’s Middle English Dance of Death has received less notice than it deserves, due to a number of factors. First of all, Lydgate’s reputation greatly declined after the sixteenth century and his ‘aureate’ style is no longer admired, which has affected the study of his work, although there has recently been a revival of Lydgate studies.2 Secondly, the poem is only a minor work in Lydgate’s huge oeuvre of well over 140,000 lines, and its didactic character has not endeared it to many literary scholars. -

Ulster-Scots

Ulster-Scots Biographies 2 Contents 1 Introduction The ‘founding fathers’ of the Ulster-Scots Sir Hugh Montgomery (1560-1636) 2 Sir James Hamilton (1559-1644) Major landowning families The Colvilles 3 The Stewarts The Blackwoods The Montgomerys Lady Elizabeth Montgomery 4 Hugh Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Sir James Montgomery of Rosemount Lady Jean Alexander/Montgomery William Montgomery of Rosemount Notable individuals and families Patrick Montgomery 5 The Shaws The Coopers James Traill David Boyd The Ross family Bishops and ministers Robert Blair 6 Robert Cunningham Robert Echlin James Hamilton Henry Leslie John Livingstone David McGill John MacLellan 7 Researching your Ulster-Scots roots www.northdowntourism.com www.visitstrangfordlough.co.uk This publication sets out biographies of some of the part. Anyone interested in researching their roots in 3 most prominent individuals in the early Ulster-Scots the region may refer to the short guide included at story of the Ards and north Down. It is not intended to section 7. The guide is also available to download at be a comprehensive record of all those who played a northdowntourism.com and visitstrangfordlough.co.uk Contents Montgomery A2 Estate boundaries McLellan Anderson approximate. Austin Dunlop Kyle Blackwood McDowell Kyle Kennedy Hamilton Wilson McMillin Hamilton Stevenson Murray Aicken A2 Belfast Road Adams Ross Pollock Hamilton Cunningham Nesbit Reynolds Stevenson Stennors Allen Harper Bayly Kennedy HAMILTON Hamilton WatsonBangor to A21 Boyd Montgomery Frazer Gibson Moore Cunningham -

Robert N. Essick and Morton D. Paley, Robert Blair's the Grave

REVIEW Robert N. Essick and Morton D. Paley, Robert Blair’s The irave, Illustrated by William Blake Andrew Wilton Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 18, Issue 1, Summer 1984, pp. 54-56 PAGE 54 BLAKE AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY SUMMER 1984 ly the black cloth boards of the binding which seem a tri- fle coarse when one thinks of the early nineteenth-cen- tury leather and marbled boards so vividly evoked by the contents. The facsimile is preceded by a series of essays: on the tradition of graveyard poetry to which Blair's poem be- longs; on the circumstances in which Blake collaborated with Robert Hartley Cromek in the publication; and on the designs that Blake made for it. There are detailed notes on the plates, and on the numerous drawings asso- ciated with The Grave but not published. By way of ap- pendices Essick and Paley add full catalogues of all these designs, referring systematically to every watercolor and sketch in Blake's oeuvre that can by any possibility be considered relevant. All these images are reproduced in adequate (though sometimes rather grey) monochrome. There is a compendium of "early references to Blake's Grave designs," largely drawn from advertisements and correspondence, taking the survey of contemporary docu- mentation up to 1813, but not including reviews, which are discussed at length in the main text. A facsimile of Cromek's advertisement for the Canterbury Pilgrims plate that Schiavonetti engraved after Stothard is also supplied, reminding us concretely of the work that caused Blake's bitter rupture with both publisher and painter.