January 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VMI History Fact Sheet

VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE Founded in 1839, Virginia Military Institute is the nation’s first state-supported military college. U.S. News & World Report has ranked VMI among the nation’s top undergraduate public liberal arts colleges since 2001. For 2018, Money magazine ranked VMI 14th among the top 50 small colleges in the country. VMI is part of the state-supported system of higher education in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The governor appoints the Board of Visitors, the Institute’s governing body. The superintendent is the chief executive officer. WWW.VMI.EDU HISTORY OF VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE 540-464-7230 INSTITUTE OFFICERS On Nov. 11, 1839, 23 young Virginians were history. On May 15, 1863, the Corps of mustered into the service of the state and, in Cadets escorted Jackson’s remains to his Superintendent a falling snow, the first cadet sentry – John grave in Lexington. Just before the Battle of Gen. J.H. Binford Peay III B. Strange of Scottsville, Va. – took his post. Chancellorsville, in which he died, Jackson, U.S. Army (retired) Today the duty of walking guard duty is the after surveying the field and seeing so many oldest tradition of the Institute, a tradition VMI men around him in key positions, spoke Deputy Superintendent for experienced by every cadet. the oft-quoted words: “The Institute will be Academics and Dean of Faculty Col. J.T.L. Preston, a lawyer in Lexington heard from today.” Brig. Gen. Robert W. Moreschi and one of the founders of VMI, declared With the outbreak of the war, the Cadet Virginia Militia that the Institute’s unique program would Corps trained recruits for the Confederate Deputy Superintendent for produce “fair specimens of citizen-soldiers,” Army in Richmond. -

The Institute Report

THE INSTITUTE REPORT Volume XVII October27,l989 Number 3 An occasional publication of the Public Information Office, Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia 24450. Tel (703) 464-7207. VMI to Celebrate 150th with Cake, Cannonade, and Convocation While its focus is clearly set on the 21st century, Events ofthe landmark year began last January VMI will spend the Nov. 10-12 weekend in celebration after several years of planning by a 17-member ofits 150th birthday and the accomplishments that VIRGINIA M1UTARY INSTITUTE Sesquicentennial Committee composed of Institute have marked the years since its opening on Nov. 11, wide representatives, including members ofthe Corps 1839. Hundreds ofalumni and special guests will joi n ofCadets. The committee has been headed by Col. intheculminating events ofthe sesquicentennial year. George M. Brooke, Jr., '36, of Lexington, emeritus The weekend program, which is listed in detail professor of history, with Col. Leonard L. Lewane, elsewhere is this publication, includes a three-day '50B, also of Lexington, as executive director of the schedule ofactivities beginning Friday, Nov. 10, with sesquicentennial office. burial of a time capsule, parade, and what promises The year-long anniversary events leading up to that evening to be a stirring and memorable concert. Founders Day November's grand finale have included special memorial observances; on Saturday will include the dedication ofthe new science hall; a con concerts; lectures; exhibits; a play; a leadership conference; several vocation; post-wide luncheons; and an afternoon football game. commemorative items, including a limited edition sesquicentennial Popular NBC weatherman Willard Scott has also been invited to medallion; and thepublication ofthree books. -

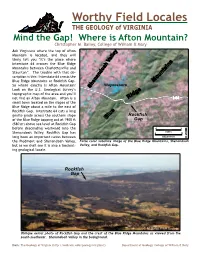

Where Is Afton Mountain? Christopher M

Worthy Field Locales THE GEOLOGY of VIRGINIA Mind the Gap! Where is Afton Mountain? Christopher M. Bailey, College of William & Mary Ask Virginians where the top of Afton y e Mountain is located, and they will ll likely tell you “it’s the place where a V s Interstate 64 crosses the Blue Ridge h n Mountains between Charlottesville and a i o ta Staunton”. The trouble with that de- d n n u scription is this: Interstate 64 crests the a o Blue Ridge Mountains at Rockfish Gap. n M e So where exactly is Afton Mountain? h Waynesboro S Look on the U.S. Geological Survey’s ge topographic map of the area and you’ll id not find an Afton Mountain. Afton is a R I-64 small town located on the slopes of the Blue Ridge about a mile to the east of Rockfish Gap. Interstate 64 cuts a long e gentle grade across the southern slope lu Rockfish of the Blue Ridge topping out at 1900 ft B Gap (580 m) above sea level at Rockfish Gap before descending westward into the 0 3 miles Shenandoah Valley. Rockfish Gap has 0 5 N long been an important nexus between kilometers the Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley, False color satellite image of the Blue Ridge Mountains, Shenandoah but as we shall see it is also a fascinat- Valley, and Rockfish Gap. ing geological locale. Rockfish Gap C. M. Bailey, W&M Geology Oblique aerial photo of Rockfish Gap and the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains as viewed from the south-southeast. -

Scenic Landforms of Virginia

Vol. 34 August 1988 No. 3 SCENIC LANDFORMS OF VIRGINIA Harry Webb . Virginia has a wide variety of scenic landforms, such State Highway, SR - State Road, GWNF.R(T) - George as mountains, waterfalls, gorges, islands, water and Washington National Forest Road (Trail), JNFR(T) - wind gaps, caves, valleys, hills, and cliffs. These land- Jefferson National Forest Road (Trail), BRPMP - Blue forms, some with interesting names such as Hanging Ridge Parkway mile post, and SNPMP - Shenandoah Rock, Devils Backbone, Striped Rock, and Lovers Leap, National Park mile post. range in elevation from Mt. Rogers at 5729 feet to As- This listing is primarily of those landforms named on sateague and Tangier islands near sea level. Two nat- topographic maps. It is hoped that the reader will advise ural lakes occur in Virginia, Mountain Lake in Giles the Division of other noteworthy landforms in the st& County and Lake Drummond in the City of Chesapeake. that are not mentioned. For those features on private Gaps through the mountains were important routes for land always obtain the owner's permission before vis- early settlers and positions for military movements dur- iting. Some particularly interesting features are de- ing the Civil War. Today, many gaps are still important scribed in more detail below. locations of roads and highways. For this report, landforms are listed alphabetically Dismal Swamp (see Chesapeake, City of) by county or city. Features along county lines are de- The Dismal Swamp, located in southeastern Virginia, scribed in only one county with references in other ap- is about 10 to 11 miles wide and 15 miles long, and propriate counties. -

Acid Rain in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia

Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Acid Rain in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia Visitors to Shenandoah National Park (SNP) enjoy the animal and plant The pH scale is a measure of how acidic (low pH) or alkaline life and the scenery but may not real- (high pH) a solution is. Rainwater is considered normal at 5.6 pH ize how vulnerable these features are to units. Shenandoah National Park rain typically is 10 times more various threats, such as invasion of exotic acidic than normal rain. plants and insects, improper use of park resources by humans, and air and water pollution. The National Park Service rain (currently about 4.6 pH units) falling mic, which means that each whole-num- strives to protect natural resources from onto an environment that has little inher- ber change indicates a 10-fold change in such threats to ensure that the resources ent ability to neutralize the acidic input acidity or alkalinity. For example, a pH of will be available for enjoyment now and and decades of exposure to acid rain have 4 is 10 times more acidic than a pH of 5. in the future. Because SNP has limited resulted in a fragile environment. When Rainwater is considered normal at 5.6 pH influence over the air pollution that the effects of acid rain are combined units; therefore, rain with a pH of 4.6, envelops the region, acidic deposition— with stressors, such as forest defoliation which typically occurs in SNP, is about commonly known as acid rain—is one of caused by the gypsy moth or conifer- 10 times more acidic than normal rain. -

History of Virginia

14 Facts & Photos Profiles of Virginia History of Virginia For thousands of years before the arrival of the English, vari- other native peoples to form the powerful confederacy that con- ous societies of indigenous peoples inhabited the portion of the trolled the area that is now West Virginia until the Shawnee New World later designated by the English as “Virginia.” Ar- Wars (1811-1813). By only 1646, very few Powhatans re- chaeological and historical research by anthropologist Helen C. mained and were policed harshly by the English, no longer Rountree and others has established 3,000 years of settlement even allowed to choose their own leaders. They were organized in much of the Tidewater. Even so, a historical marker dedi- into the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes. They eventually cated in 2015 states that recent archaeological work at dissolved altogether and merged into Colonial society. Pocahontas Island has revealed prehistoric habitation dating to about 6500 BCE. The Piscataway were pushed north on the Potomac River early in their history, coming to be cut off from the rest of their peo- Native Americans ple. While some stayed, others chose to migrate west. Their movements are generally unrecorded in the historical record, As of the 16th Century, what is now the state of Virginia was but they reappear at Fort Detroit in modern-day Michigan by occupied by three main culture groups: the Iroquoian, the East- the end of the 18th century. These Piscataways are said to have ern Siouan and the Algonquian. The tip of the Delmarva Penin- moved to Canada and probably merged with the Mississaugas, sula south of the Indian River was controlled by the who had broken away from the Anishinaabeg and migrated Algonquian Nanticoke. -

The Louisa Railroad (1836-1850) Charles W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1937 The Louisa Railroad (1836-1850) Charles W. Turner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Turner, Charles W., "The Louisa Railroad (1836-1850)" (1937). Honors Theses. 1051. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1051 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITYOF RIC HMONDLIB RARIES llllll~llll~~iililllllllm~llll~IIIIII _ . 3 3082 01028 3231 THE· 'LOUISA RAILROAD (1836-1850) History Thesis May 24 ,1937. Presented by Charles w. Turner. (In this paper, there will be found facts concerning the lives of many of the characters connected with the railroad.) BIBLIOGRAPHY Books 1. Freeman, D.S., R. E. Lee, Vol. II, III, IV, Charles Scribners Sons, NewYork, N. Y., l934-36. 2. Harris, Malcohn H., ~ History of Louisa County, Virg~n1a, The Dietz Presa, Ric~mond, V1rg1n1a, 1937. 3. Morton, R. L., Historx of V1r5lnia, Vol. III, Amertcan Historical Society, New York, N. Y. 1924. 4. Nelson, James P., Hlstor~ of the c. and o. Ra11 a~ Co., I.ew1e Printing Company, R1cnmond, -VirginTa, -r~ 7. -- Newspapers and Magazines 6. Reli6ious He~ald, ~eb. 13, 1873~ 7. Richmond Ingui-rer, 1835-50• 8. Stanard, W. G. ed., Virginia Historical Magazine, Vol. XXIX, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia, 1921. · 9. Stanard, w. -

Railroad Building in Virginia (1827 to 1860)

Railroad Building in Virginia (1827 to 1860) Virginia History Series #10-08 © 2008 Major Railroads in Virginia (from 1827-1860) • Baltimore and Ohio (1827) – Winchester & Potomac (at Harpers Ferry) – Winchester & Strasburg • South Side or “Petersburg & -- North Western to Lynchburg RR” (1849-54) Parkersburg, WV • Richmond & Danville (1847-1856) • Manassas Gap (1850-54) • Petersburg & Roanoke (river in NC) • Orange & Alexandria (1848) (1833) -- Richmond & Petersburg (1838) • Virginia Central (1836) -- Blue Ridge (1858) • Norfolk and Petersburg (1853) • Virginia & Tennessee (1850s) • Seaboard & Roanoke (river in NC) or “Portsmouth and Weldon RR” (1835) • Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac to Alexandria (1834) & Fredericksburg & Charlottesville RR Major RR Routes in Virginia by 1860 Wheeling●, Ohio River Parkersburg ● ● Grafton Maryland & York RR+ + ++++++/ + Norfolk Stn + Petersburg & + Norfolk RR + + + + Suffolk Stn + + Bristol ● + + + + Norfolk & + Roanoke RR Weldon ■ On March 8, 1827, the Commonwealth of Virginia joined Maryland in giving the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road (B&O RR) the task of building a railroad from the port of Baltimore, MD West to a suitable point on the Ohio River. The railroad was intended to provide a faster route for Midwestern goods to reach the East Coast than the successful Erie Canal across upstate NY. Construction began on July 4th, 1828. It was decided to follow the Patapsco River to a point near where the railroad would cross the “fall line” and descend into the valley of the Monocacy and Potomac Rivers. Thomas Viaduct (on the B&O RR) spans the Patapsco River and Patapsco Valley between Relay and Elkridge, MD (1833-35) It was the largest bridge in the nation and today its still the world's oldest multiple arched stone railroad bridge Further extensions of the B&O RR soon opened to Frederick and Point of Rocks on the Potomac river. -

Addendum No. 2

Addendum No. 2 Issue Date: 22 May 2017 To: Bidding Contractors - Plan Holders Project: Blue Ridge (Crozet) Tunnel Rehabilitation and Trail Project Nelson County Board of Supervisors The following items are being issued here for clarification, addition or deletion and have been incorporated into the Construction Documents and Project Manual, and shall be included as part of the bid documents. All Contractors shall acknowledge this Addendum No. 2 in the Bid Form. Failure of acknowledgment may result in rejection of your bid. All Bidders shall be responsible for seeing that their subcontractors are properly apprised of the contents of this addendum. BID DATE AND TIME: 1. The sign in sheet from the pre-bid meeting held on Friday May 12 th is included with Addenda 2. 2. At this time, the bid opening remains May 31 st at 2.00 PM. CLARIFICATIONS / CONTRACTOR QUESTIONS: 1. Q: The unit of measurement for the aggregate base material is in cubic yards. Can the units be revised to reflect the number of tons? A: Section 607.12 Unit Costs and Measures provides for the acceptable units for measurement. The quantity reflected in the bid form is based upon the area x thickness of the material. Please note that the volume is measured as “in-place and does not account for any volumetric loss due to compaction. The conversion from cubic yards to tons is based upon the unit weight of the material. For example, assuming a unit weight of 130 lbs/ft 3, which may be considered normal for VDOT 21B material, the conversion to tons would be 1 CY x (27 ft 3 / yd 3) x (130 lbs/ft 3) x (1 ton/2000 lbs). -

Century West Point and the Invention of the Blackboard

An Officer and a Scholar: Nineteenth-Century West Point and the Invention of the Blackboard Christopher J. Phillips Over two centuries after the invention of blackboards, they still fea- ture prominently in many American classrooms. The blackboard has outlasted most other educational innovations and technologies, and has always been more than an aide memoire. Students and teachers have long assumed inscriptions on its surface made mental processes visible. As early as 1880, in fact, the A.H. Andrews & Co. catalog described the blackboard as a “mirror reflecting the workings, character, and quality of the individual mind.”1 The blackboard’s ultimate origins are un- clear but in North America one institution, the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, played a particularly important Christopher J. Phillips is an Assistant Professor & Faculty Fellow at the NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study and has been appointed assistant professor in Carnegie Mellon University’s Department of History. For help with the preparation of this arti- cle, he would like to especially acknowledge Michael Barany, Bruno Belhoste, Stephanie Dick, Peggy Kidwell, Fred Rickey, David Roberts, Brittany Shields, and Alma Steingart, as well as audiences at meetings of the History of Science Society and American Math- ematical Society, and the anonymous referees for History of Education Quarterly. He also wishes to thank the librarians and archivists of the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. 1A.H. Andrews & Co., Illustrated Catalogue of School Merchandise (Chicago, IL: A.H. Andrews & Co.,1881), 73, quoted in David Tyack and Larry Cuban, Tinkering Toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 121. -

Download Guidebook to Richmond

SIA RVA SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY 47th ANNUAL CONFERENCE MAY 31 - JUNE 3, 2018 RICHMOND, VIRGINIA GUIDEBOOK TO RICHMOND SIA RVA SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY 47th ANNUAL CONFERENCE MAY 31 - JUNE 3, 2018 RICHMOND, VIRGINIA OMNI RICHMOND HOTEL GUIDEBOOK TO RICHMOND SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHEOLOGY MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 1400 TOWNSEND DRIVE HOUGHTON, MI 49931-1295 www.sia-web.org i GUIDEBOOK EDITORS Christopher H. Marston Nathan Vernon Madison LAYOUT Daniel Schneider COVER IMAGE Philip Morris Leaf Storage Ware house on Richmond’s Tobacco Row. HABS VA-849-31 Edward F. Heite, photog rapher, 1969. ii CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION Richmond’s Industrial Heritage .............................................................. 3 THURSDAY, MAY 31, 2018 T1 - The University of Virginia ................................................................19 T1 - The Blue Ridge Tunnel ....................................................................22 T2 - Richmond Waterfront Walking Tour ..............................................24 T3 - The Library of Virginia .....................................................................26 FRIDAY, JUNE 1, 2018 F1 - Strickland Machine Company ........................................................27 F1 - O.K. Foundry .....................................................................................29 F1 & F2 - Tobacco Row / Philip Morris USA .......................................32 F1 & -

HISTORIC SITE FILE: 13\AC.-K L°'-Nd \It ?Ftj R-1 ~ !);- 5Ft-;

HISTORIC SITE FILE: 13\AC.-K l°'-nd \it ?ftJ r-1~ !);-_5ft-; c r -PRINCE WILLIAM PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM'l!>1=111!J=r :!. !J!J!J RELIC/Bull Run Reg Lib, Manassas, VA A LESSON IN "In my opinion, properly protected and n an area rife with American history researched. Buckland has the unique I - monuments, President's homes, potential to teach generations to come Civil War battlefields - there is one place nearby that can hold its own much about American values. especially wirh anything anybody else has to offer. the role of free enterprise, in the develop You've probably never heard of it, but if ment and growth of the U.S. during its you've lived in the area for any length founding years between the American of time, you've probably driven past Revolution and the Civil War Era. Too it hundreds of times, maybe - if you often, as at Jamestown. no architectural commute to work in Northern Virginia evidence and few documents survive to - even thousands of times. The place? help tell significant pieces of the story as It's Buckland, just over the county line it does at Buckland." in Prince William County. So, exactly what kind of history are William M. Kelso, Ph.D. we talking about here? Well, how about APVA Director of Archeology Jamestown Rediscovery Native American burial mounds to start. Then add in all the luminaries from the birth of this nation - George Washingron, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson. Toss in a couple of foreigners The landscape has not changed much from this October I8 1 1863 drawing by Alfred Waud (scene of calvary engagement with Stuart) and the Buckland Preservation like the Marquis de Lafayette and Society is working hard to keep it that way.