Download Guidebook to Richmond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Form

VLR Listing - 9/6/2006 Vi-/-· 11/1,/1, NRHP Listing - 11/3/2006 ,·~ (-µ{ :.,1(1-i C ' ,ps Form 10·900 0."\18 :\'o. !024-4018 \Ill',·. 10·90) 11. S. Department or the lnh.·:r-ior Town of Bermuda Hundred Historic District ~ational Park Sen'ice Chesterfield Co .. VA '.\TATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This ronn is for use in nomir,ating or requesting d~enninations for individual properties and districts. See instruction.~ in l-lo~vto Complete the National Rcg1sler ofHi~tor1c Places Registration Forrn {National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each Hem by marking "x" in the appropnate box or bycntcnng :he information requcs!cd IC any item does not apply to the property bein~ documented, enter "NIA" for "no: applicable." For functions, architectural ,·las.~ification, nrnteriu!s, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative •terns on con1inuat1011 sheets (NPS Form J 0·900a). Use a t)i)ewflter, word processor, or eompuler, lo complete all items. I. Name of Pro ert ' Historic t<ame: Town ofBennuda Hundred Historic District other names/site number VDHR #020-0064 2. Location street & number_~B~o~t~h~s~id~e~s~o=f~B~e~nn=u~d~•~H=u~n~d~re~d~•n~d~A~l~li~e~d~R~o~a~d~s~______ not for publication ___ _ city or town Chester vicinity_,~X~-- :itate Virginia code VA eounty Chesterfield ____ code 041 Zip _2382 J 3. State/Federal Agency Certification !\s the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, J hereby certify that lhis _x_ nomina11on __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering propenies in the Narional Register ofHmoric Place~ and meets the procedural and professional requirements sel forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

VMI History Fact Sheet

VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE Founded in 1839, Virginia Military Institute is the nation’s first state-supported military college. U.S. News & World Report has ranked VMI among the nation’s top undergraduate public liberal arts colleges since 2001. For 2018, Money magazine ranked VMI 14th among the top 50 small colleges in the country. VMI is part of the state-supported system of higher education in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The governor appoints the Board of Visitors, the Institute’s governing body. The superintendent is the chief executive officer. WWW.VMI.EDU HISTORY OF VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE 540-464-7230 INSTITUTE OFFICERS On Nov. 11, 1839, 23 young Virginians were history. On May 15, 1863, the Corps of mustered into the service of the state and, in Cadets escorted Jackson’s remains to his Superintendent a falling snow, the first cadet sentry – John grave in Lexington. Just before the Battle of Gen. J.H. Binford Peay III B. Strange of Scottsville, Va. – took his post. Chancellorsville, in which he died, Jackson, U.S. Army (retired) Today the duty of walking guard duty is the after surveying the field and seeing so many oldest tradition of the Institute, a tradition VMI men around him in key positions, spoke Deputy Superintendent for experienced by every cadet. the oft-quoted words: “The Institute will be Academics and Dean of Faculty Col. J.T.L. Preston, a lawyer in Lexington heard from today.” Brig. Gen. Robert W. Moreschi and one of the founders of VMI, declared With the outbreak of the war, the Cadet Virginia Militia that the Institute’s unique program would Corps trained recruits for the Confederate Deputy Superintendent for produce “fair specimens of citizen-soldiers,” Army in Richmond. -

Environmental Assessment for a Marketing Order for a New Combusted, Filtered Cigarette Manufactured by Philip Morris USA Inc

Environmental Assessment for a Marketing Order for a New Combusted, Filtered Cigarette Manufactured by Philip Morris USA Inc. Prepared by Center for Tobacco Products U.S. Food and Drug Administration May 7, 2019 Table of Contents 1. Applicant and Manufacturer Information .......................................................................................... 3 2. Product Information ............................................................................................................................ 3 3. The Need for the Proposed Action ...................................................................................................... 3 4. Alternative to the Proposed Action .................................................................................................... 3 5. Potential Environmental Impacts of the Proposed Action and Alternative - Manufacturing the New Product ............................................................................................................................................. 4 5.1 Affected Environment.. ....................................................................................................... 4 5.2 Air Quality ........................................................................................................................... 5 5.3 Water Resources ................................................................................................................. 5 5.4 Soil, Land Use, and Zoning ................................................................................................. -

The Institute Report

THE INSTITUTE REPORT Volume XVII October27,l989 Number 3 An occasional publication of the Public Information Office, Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia 24450. Tel (703) 464-7207. VMI to Celebrate 150th with Cake, Cannonade, and Convocation While its focus is clearly set on the 21st century, Events ofthe landmark year began last January VMI will spend the Nov. 10-12 weekend in celebration after several years of planning by a 17-member ofits 150th birthday and the accomplishments that VIRGINIA M1UTARY INSTITUTE Sesquicentennial Committee composed of Institute have marked the years since its opening on Nov. 11, wide representatives, including members ofthe Corps 1839. Hundreds ofalumni and special guests will joi n ofCadets. The committee has been headed by Col. intheculminating events ofthe sesquicentennial year. George M. Brooke, Jr., '36, of Lexington, emeritus The weekend program, which is listed in detail professor of history, with Col. Leonard L. Lewane, elsewhere is this publication, includes a three-day '50B, also of Lexington, as executive director of the schedule ofactivities beginning Friday, Nov. 10, with sesquicentennial office. burial of a time capsule, parade, and what promises The year-long anniversary events leading up to that evening to be a stirring and memorable concert. Founders Day November's grand finale have included special memorial observances; on Saturday will include the dedication ofthe new science hall; a con concerts; lectures; exhibits; a play; a leadership conference; several vocation; post-wide luncheons; and an afternoon football game. commemorative items, including a limited edition sesquicentennial Popular NBC weatherman Willard Scott has also been invited to medallion; and thepublication ofthree books. -

Directory for Cigarettes and Roll-Your-Own Tobacco

DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL STATE OF HAWAI‘I DIRECTORY FOR CIGARETTES AND ROLL-YOUR-OWN TOBACCO of (Available at: http://ag.hawaii.gov/cjd/tobacco-enforcement-unit/) Certified Tobacco Product Manufacturers Their Brands and Brand Families DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL TOBACCO ENFORCEMENT UNIT 425 QUEEN STREET HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I 96813 (808) 586-1203 INDEX I. Directory: Cigarettes and Roll-Your-Own Tobacco Page 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. DEFINITIONS 3 3. NOTICES 5 II. Update Summary For September 22, 2017 Posting III. Alphabetical Brand List IV. Compliant Participating Manufacturers List V. Compliant Non-Participating Manufacturers List Posted: September 22, 2017 2 1. INTRODUCTION Pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat. §245-22.5(a), beginning December 1, 2003, it shall be unlawful for an entity (1) to affix a stamp to a package or other container of cigarettes belonging to a tobacco product manufacturer or brand family not included in this directory, or (2) to import, sell, offer, keep, store, acquire, transport, distribute, receive, or possess for sale or distribution cigarettes1 belonging to a tobacco product manufacturer or brand family not included in this directory. Pursuant to §245-22.5(b), any entity that knowingly violates subsection (a) shall be guilty of a class C felony. Pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat. §§245-40 and 245-41, any cigarettes unlawfully possessed, kept, stored, acquired, transported, or sold in violation of Haw. Rev. Stat. §245-22.5 may be ordered forfeited pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat., Chapter 712A. In addition, the attorney general may apply for a temporary or permanent injunction restraining any person from violating or continuing to violate Haw. -

Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity by Kiun H

Title Page Framing, Walking, and Reimagining Landscapes in a Post-Soviet St. Petersburg: Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity by Kiun Hwang Undergraduate degree, Yonsei University, 2005 Master degree, Yonsei University, 2008 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Kiun Hwang It was defended on November 8, 2019 and approved by David Birnbaum, Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of History of Art & Architecture Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Condee, Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures ii Copyright © by Kiun Hwang 2019 Abstract iii Framing, Walking, and Reimagining Landscapes in a Post-Soviet St. Petersburg: Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity Kiun Hwang, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 St. Petersburg’s image and identity have long been determined by its geographical location and socio-cultural foreignness. But St. Petersburg’s three centuries have matured its material authenticity, recognizable tableaux and unique urban narratives, chiefly the Petersburg Text. The three of these, intertwined in their formation and development, created a distinctive place-identity. The aura arising from this distinctiveness functioned as a marketable code not only for St. Petersburg’s heritage industry, but also for a future-oriented engagement with post-Soviet hypercapitalism. Reflecting on both up-to-date scholarship and the actual cityscapes themselves, my dissertation will focus on the imaginative landscapes in the historic center of St. -

Michael Pearson, the Sealed Train

Michael Pearson, The Sealed Train The Sealed Train There is little doubt that his decision for the immediate leap into the second stage of revolution was made after leaving Switzerland ● Foreword and before arriving in Russia. ● Chapter 1 ● Chapter 2 ● Chapter 3 ● Arrange for train ● Get on train The ● Into Germany SEALED TRAIN ● Berlin big idea ● Chapter 8 ● Chapter 9 ● Chapter 10 Michael Pearson ● Chapter 11 ● Chapter 12 ● Chapter 13 ● Chapter 14 ● Chapter 15 ● Chapter 16 ● Chapter 17 Pearson, Michael ● Afterword The sealed train New York : Putnam, [1975] ISBN 0399112626 Lenin : The Compulsive Revolutionary ● German contact ● Lenin Realizes His Power ● The Sealed Car and the idea of Leninism ● Accusation Treason ● Armed Uprising http://www.yamaguchy.netfirms.com/pearson/oktszocforr.html29.10.2005 19:24:19 Pearson, Sealed Train, Foreword Michael Pearson : The Sealed Train New York : Putnam, 1975, 320 p. ISBN : 0399112626 Foreword IN MARCH, 1917, Lenin was living in Zurich in poverty, the exiled head of a small extremist revolutionary party that had relatively little following even within Russia. Eight months later, he assumed the rule of 160,000,000 people occupying one-sixth of the inhabited surface of the world. The Sealed Train is the story of those thirty-four fantastic weeks. The train itself and the bizarre journey across Germany, then at war with Russia, are a vital and dramatic link in the story. For without the train, Lenin could not have reached St. Petersburg when he did, and if Lenin had not returned to Russia, the history of the world would have been very different. For not one of his comrades had the sense of timing, the strength of will, the mental agility, the subtle understanding of the ever-changing mood of the people and the sheer intellectual power of Lenin. -

Springfield Railroad Underpass Project Hampshire County State Project # S314-SBV-RR-6.50 Federal Project # N/A FR#: 15-479-HM

Springfield Railroad Underpass Project Hampshire County State Project # S314-SBV-RR-6.50 Federal Project # N/A FR#: 15-479-HM HISTORIC DOCUMENTATION July 2015 West Virginia Department of Transportation Division of Highways Engineering Division Environmental Section (304) 558-2885 HISTORIC DOCUMENTATION SPRINGFIELD RAILROAD UNDERPASS BRIDGE Location: West Virginia State Route 28 and Abernathy Run Springfield Hampshire County West Virginia USGS Springfield Quadrangle Date of Construction: circa 1880 Builder: South Branch Railroad Company Present Owner: West Virginia State Rail Authority 120 Water Plant Drive Moorefield, WV 26836 Present Use: Railroad Bridge Significance: The Springfield Railroad Underpass is significant on the local level with a period of significance 1890 to 1952. Project Information: The project has been undertaken due to the poor condition of the Underpass bridge. Any future deterioration of the underpass bridge will result in its closure, the existing underpass warrants replacement. The documentation was undertaken in July 2015 in accordance with a Memorandum of Agreement among the West Virginia Department of Transportation and West Virginia State Historic Preservation Office. These measures are required prior to replacement of this National Register eligible structure. Sondra L. Mullins, Structural Historian West Virginia Division of Highways Charleston, WV 25301 July 10, 2015 Springfield Railroad Underpass Page 2 BALTIMORE & OHIO RAILROAD HISTORY The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company (B & O) was chartered on February 28, 1827 by businessmen from Baltimore, Maryland. The goal of the businessmen was to ensure that traffic was not lost to the proposed Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. By the end of the 19th century the B & O had almost 5,800 miles of track connecting Chicago and St. -

History of Virginia

14 Facts & Photos Profiles of Virginia History of Virginia For thousands of years before the arrival of the English, vari- other native peoples to form the powerful confederacy that con- ous societies of indigenous peoples inhabited the portion of the trolled the area that is now West Virginia until the Shawnee New World later designated by the English as “Virginia.” Ar- Wars (1811-1813). By only 1646, very few Powhatans re- chaeological and historical research by anthropologist Helen C. mained and were policed harshly by the English, no longer Rountree and others has established 3,000 years of settlement even allowed to choose their own leaders. They were organized in much of the Tidewater. Even so, a historical marker dedi- into the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes. They eventually cated in 2015 states that recent archaeological work at dissolved altogether and merged into Colonial society. Pocahontas Island has revealed prehistoric habitation dating to about 6500 BCE. The Piscataway were pushed north on the Potomac River early in their history, coming to be cut off from the rest of their peo- Native Americans ple. While some stayed, others chose to migrate west. Their movements are generally unrecorded in the historical record, As of the 16th Century, what is now the state of Virginia was but they reappear at Fort Detroit in modern-day Michigan by occupied by three main culture groups: the Iroquoian, the East- the end of the 18th century. These Piscataways are said to have ern Siouan and the Algonquian. The tip of the Delmarva Penin- moved to Canada and probably merged with the Mississaugas, sula south of the Indian River was controlled by the who had broken away from the Anishinaabeg and migrated Algonquian Nanticoke. -

Charles Olivier and the Rise of Meteor Science

Springer Biographies Charles Olivier and the Rise of Meteor Science RICHARD TAIBI Springer Biographies More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/13617 Richard Taibi Charles Olivier and the Rise of Meteor Science 123 Richard Taibi Temple Hills, MD USA ISSN 2365-0613 ISSN 2365-0621 (electronic) Springer Biographies ISBN 978-3-319-44517-5 ISBN 978-3-319-44518-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-44518-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016949123 © Richard Taibi 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors -

At Pocahontas Island City of Petersburg, Virginia

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF SIX SITES (44PG5, 44PG470, 44PG471, 44PG472, 44PG473, and 44PG474) AT POCAHONTAS ISLAND CITY OF PETERSBURG, VIRGINIA VOLUME I: RESULTS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL TESTING Prepared For: Department of Planning and Community Development City of Petersburg 135 N. Union Street Petersburg, Virginia 23803 Prepared By: Matthew Laird (Ph.D.) James River Institute for Archaeology, Inc. 223 McLaws Circle, Suite 1 Williamsburg, Virginia 23185 (757) 229-9485 September 2006 ABSTRACT Between December 2005 and April 2006, the James River Institute for Archaeology, Inc. (JRIA), conducted intensive archaeological testing of six sites within the Pocahontas Island Historic District. The objective of the testing, which focused primarily on properties owned by the City of Petersburg, was to evaluate the integrity and research potential of a representative sample of site types encompassing both the prehistoric- and historic-period occupations of Pocahontas Island. The resources examined included the archaeological components of the extant Jarratt House (44PG470) and “Underground Railroad House” (44PG471); the site of the former Richmond & Petersburg Railroad depot (44PG472); a domestic site spanning the eighteenth- through twentieth centuries in the vacant lot at 301 Rolfe Street (44PG473); the former site of the early twentieth- century Pocahontas Distilling Co. whiskey distillery at 343 Rolfe Street, which also included a nineteenth-/twentieth-century domestic component (44PG474); and one previously inventoried site (44PG5) with prehistoric Native-American and historic domestic components. In general, the investigated sites retained a high degree of physical integrity, and yielded significant concentrations of artifacts and evidence of intact cultural layers and features. Individually, the six sites retained sufficient integrity and research potential to be considered eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion D. -

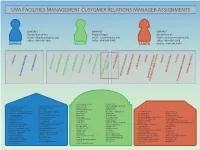

Uva Facilities Management Customer Relations Manager Assignments

UVA FACILITIES MANAGEMENT CUSTOMER RELATIONS MANAGER ASSIGNMENTS CONTACT CONTACT CONTACT Dennis Bianchetto Reggie Steppe Sarita Herman email - [email protected] email - [email protected] email - [email protected] oce - 434-243-1092 oce - 434-243-2442 oce - 434-924-1958 DENNIS REGGIE SARITA mobile - 434-981-0647 LIBRARY FINANCE IT VP/CIO PROVOST ATHLETICS CURRY SCHOOL ARTS GROUNDS BATTEN SCHOOL SCIENCES STUDENT AFFAIRS MCINTIRE SCHOOL EXECUTIVE VP/COO HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT & UR PRESIDENT’S OFFICE RES & PUBLIC SERVICE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND ENGINEERING SCHOOL BUSINESS OPERATIONS DIVERSITY AND EQUITY ARCHITECTURE SCHOOL SCHOOL OF CONTINUING VP MANAGEMENT & BUDGET AND PROFESSIONAL STUDIES ASTRONOMY BUILDING KERCHOF HALL AQUATIC & FITNESS CENTER NORTH GROUNDS RECREATION CTR BAYLY BUILDING LORNA SUNDBERG INT’L CTR ARENA PARKING GARAGE OHILL DINING FACILITY BEMISS HOUSE MADISON HALL BASEBALL STADIUM ONESTY HALL BIOLOGY GREENHOUSE MAURY HALL BOOKSTORE/CENTRAL GROUNDS PRKG OUTDOOR RECREATION CENTER BOOKER HOUSE MCCORMICK OBSERVATORY 2200 OLD IVY ROAD LAMBETH HOUSE CARR'S HILL FIELD SUPPORT FACILITY PARKING & TRANSIT BROOKS HALL MINOR HALL 315 OLD IVY WAY MADISON HOUSE CHILD CARE CENTER PAVILION VII/COLONNADE CLUB BRYAN HALL MONROE HALL 350 OLD IVY WAY MATERIALS SCIENCE CULBRETH ROAD GARAGE PRINTING SERVICE CENTER CARR’S HILL NEW CABELL HALL AEROSPACE RESEARCH LABORATORY MECHANICAL ENGINEERING EMMET/IVY GARAGE RUNK DINING HALL CHEMISTRY BUILDING OLD CABELL HALL ALBERT H SMALL BUILDING MICHIE BUILDINGS ERN COMMONS SCOTT STADIUM CLARK HALL PEABODY HALL ALDERMAN LIBRARY MUSIC LIBRARY - OLD CABELL HALL FONTANA FOOD CENTER SHELBURNE HALL/HIGHWAY RESEARCH COCKE HALL PHYSICAL AND LIFE SCIENCES BAVARO HALL OBSERVATORY MTN ENGINEERING RESEARCH FORESTRY BUILDING GARAGE SLAUGHTER RECREATION CENTER DAWSON'S ROW PHYSICS/J BEAMS LAB BROWN LIBRARY - CLARK HALL OLSSON HALL FRANK C.