EPISODES from the EARLY HISTORY of MATHEMATICS By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

Arc Length. Surface Area

Calculus 2 Lia Vas Arc Length. Surface Area. Arc Length. Suppose that y = f(x) is a continuous function with a continuous derivative on [a; b]: The arc length L of f(x) for a ≤ x ≤ b can be obtained by integrating the length element ds from a to b: The length element ds on a sufficiently small interval can be approximated by the hypotenuse of a triangle with sides dx and dy: p Thus ds2 = dx2 + dy2 ) ds = dx2 + dy2 and so s s Z b Z b q Z b dy2 Z b dy2 L = ds = dx2 + dy2 = (1 + )dx2 = (1 + )dx: a a a dx2 a dx2 2 dy2 dy 0 2 Note that dx2 = dx = (y ) : So the formula for the arc length becomes Z b q L = 1 + (y0)2 dx: a Area of a surface of revolution. Suppose that y = f(x) is a continuous function with a continuous derivative on [a; b]: To compute the surface area Sx of the surface obtained by rotating f(x) about x-axis on [a; b]; we can integrate the surface area element dS which can be approximated as the product of the circumference 2πy of the circle with radius y and the height that is given by q the arc length element ds: Since ds is 1 + (y0)2dx; the formula that computes the surface area is Z b q 0 2 Sx = 2πy 1 + (y ) dx: a If y = f(x) is rotated about y-axis on [a; b]; then dS is the product of the circumference 2πx of the circle with radius x and the height that is given by the arc length element ds: Thus, the formula that computes the surface area is Z b q 0 2 Sy = 2πx 1 + (y ) dx: a Practice Problems. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

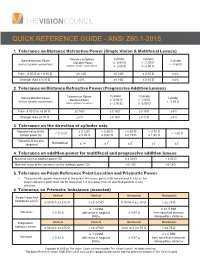

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

Cones, Pyramids and Spheres

The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 12 CONES, PYRAMIDS AND SPHERES A guide for teachers - Years 9–10 June 2011 YEARS 910 Cones, Pyramids and Spheres (Measurement and Geometry : Module 12) For teachers of Primary and Secondary Mathematics 510 Cover design, Layout design and Typesetting by Claire Ho The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project 2009‑2011 was funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. © The University of Melbourne on behalf of the International Centre of Excellence for Education in Mathematics (ICE‑EM), the education division of the Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute (AMSI), 2010 (except where otherwise indicated). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. 2011. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‑nc‑nd/3.0/ The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 12 CONES, PYRAMIDS AND SPHERES A guide for teachers - Years 9–10 June 2011 Peter Brown Michael Evans David Hunt Janine McIntosh Bill Pender Jacqui Ramagge YEARS 910 {4} A guide for teachers CONES, PYRAMIDS AND SPHERES ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE • Familiarity with calculating the areas of the standard plane figures including circles. • Familiarity with calculating the volume of a prism and a cylinder. • Familiarity with calculating the surface area of a prism. • Facility with visualizing and sketching simple three‑dimensional shapes. • Facility with using Pythagoras’ theorem. • Facility with rounding numbers to a given number of decimal places or significant figures. -

Lateral and Surface Area of Right Prisms 1 Jorge Is Trying to Wrap a Present That Is in a Box Shaped As a Right Prism

CHAPTER 11 You will need Lateral and Surface • a ruler A • a calculator Area of Right Prisms c GOAL Calculate lateral area and surface area of right prisms. Learn about the Math A prism is a polyhedron (solid whose faces are polygons) whose bases are congruent and parallel. When trying to identify a right prism, ask yourself if this solid could have right prism been created by placing many congruent sheets of paper on prism that has bases aligned one above the top of each other. If so, this is a right prism. Some examples other and has lateral of right prisms are shown below. faces that are rectangles Triangular prism Rectangular prism The surface area of a right prism can be calculated using the following formula: SA 5 2B 1 hP, where B is the area of the base, h is the height of the prism, and P is the perimeter of the base. The lateral area of a figure is the area of the non-base faces lateral area only. When a prism has its bases facing up and down, the area of the non-base faces of a figure lateral area is the area of the vertical faces. (For a rectangular prism, any pair of opposite faces can be bases.) The lateral area of a right prism can be calculated by multiplying the perimeter of the base by the height of the prism. This is summarized by the formula: LA 5 hP. Copyright © 2009 by Nelson Education Ltd. Reproduction permitted for classrooms 11A Lateral and Surface Area of Right Prisms 1 Jorge is trying to wrap a present that is in a box shaped as a right prism. -

Unit 3, Lesson 1: How Well Can You Measure?

GRADE 7 MATHEMATICS NAME DATE PERIOD Unit 3, Lesson 1: How Well Can You Measure? 1. Estimate the side length of a square that has a 9 cm long diagonal. 2. Select all quantities that are proportional to the diagonal length of a square. A. Area of a square B. Perimeter of a square C. Side length of a square 3. Diego made a graph of two quantities that he measured and said, “The points all lie on a line except one, which is a little bit above the line. This means that the quantities can’t be proportional.” Do you agree with Diego? Explain. 4. The graph shows that while it was being filled, the amount of water in gallons in a swimming pool was approximately proportional to the time that has passed in minutes. a. About how much water was in the pool after 25 minutes? b. Approximately when were there 500 gallons of water in the pool? c. Estimate the constant of proportionality for the number of gallons of water per minute going into the pool. Unit 3: Measuring Circles Lesson 1: How Well Can You Measure? 1 GRADE 7 MATHEMATICS NAME DATE PERIOD Unit 3: Measuring Circles Lesson 1: How Well Can You Measure? 2 GRADE 7 MATHEMATICS NAME DATE PERIOD Unit 3, Lesson 2: Exploring Circles 1. Use a geometric tool to draw a circle. Draw and measure a radius and a diameter of the circle. 2. Here is a circle with center and some line segments and curves joining points on the circle. Identify examples of the following. -

Archimedes and Pi

Archimedes and Pi Burton Rosenberg September 7, 2003 Introduction Proposition 3 of Archimedes’ Measurement of a Circle states that π is less than 22/7 and greater than 223/71. The approximation πa ≈ 22/7 is referred to as Archimedes Approximation and is very good. It has been reported that a 2000 B.C. Babylonian approximation is πb ≈ 25/8. We will compare these two approximations. The author, in the spirit of idiot’s advocate, will venture his own approximation of πc ≈ 19/6. The Babylonian approximation is good to one part in 189, the author’s, one part in 125, and Archimedes an astonishing one part in 2484. Archimedes’ approach is to circumscribe and inscribe regular n-gons around a unit circle. He begins with a hexagon and repeatedly subdivides the side to get 12, 24, 48 and 96-gons. The semi-circumference of these polygons converge on π from above and below. In modern terms, Archimede’s derives and uses the cotangent half-angle formula, cot x/2 = cot x + csc x. In application, the cosecant will be calculated from the cotangent according to the (modern) iden- tity, csc2 x = 1 + cot2 x Greek mathematics dealt with ratio’s more than with numbers. Among the often used ratios are the proportions among the sides of a triangle. Although Greek mathematics is said to not know trigonometric functions, we shall see how conversant it was with these ratios and the formal manipulation of ratios, resulting in a theory essentially equivalent to that of trigonometry. For the circumscribed polygon We use the notation of the Dijksterhuis translation of Archimedes. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

He One and the Dyad: the Foundations of Ancient Mathematics1 What Exists Instead of Ininite Space in Euclid’S Elements?

ARCHIWUM HISTORII FILOZOFII I MYŚLI SPOŁECZNEJ • ARCHIVE OF THE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY AND SOCIAL THOUGHT VOL. 59/2014 • ISSN 0066–6874 Zbigniew Król he One and the Dyad: the Foundations of Ancient Mathematics1 What Exists Instead of Ininite Space in Euclid’s Elements? ABSTRACT: his paper contains a new interpretation of Euclidean geometry. It is argued that ancient Euclidean geometry was created in a quite diferent intuitive model (or frame), without ininite space, ininite lines and surfaces. his ancient intuitive model of Euclidean geometry is reconstructed in connection with Plato’s unwritten doctrine. he model cre- ates a kind of “hermeneutical horizon” determining the explicit content and mathematical methods used. In the irst section of the paper, it is argued that there are no actually ininite concepts in Euclid’s Elements. In the second section, it is argued that ancient mathematics is based on Plato’s highest principles: the One and the Dyad and the role of agrapha dogmata is unveiled. KEYWORDS: Euclidean geometry • Euclid’s Elements • ancient mathematics • Plato’s unwrit- ten doctrine • philosophical hermeneutics • history of science and mathematics • philosophy of mathematics • philosophy of science he possibility to imagine all of the theorems from Euclid’s Elements in a Tquite diferent intuitive framework is interesting from the philosophical point of view. I can give one example showing how it was possible to lose the genuine image of Euclidean geometry. In many translations into Latin (Heiberg) and English (Heath) of the theorems from Book X, the term “area” (spatium) is used. For instance, the translations of X. 26 are as follows: ,,Spatium medium non excedit medium spatio rationali” and “A medial area does not exceed a medial area by a rational area”2.