Evolutionary Implications on Contextualism John Mark Gowan University of Missouri-St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolutionäre Erkenntnistheorie Als Grundlage Eines Aufgeklärten Kritischen Rationalismus

Evolutionäre Erkenntnistheorie als Grundlage eines aufgeklärten Kritischen Rationalismus Peter Kappelhoff Februar 2003 1. Einleitung „Der sogenannte „Konstruktivismus“ ist ... die gefährlichste moderne geistige Tendenz, und, so darf man wohl sagen, eine der am weitesten verbreiteten Auffassungen. Er verbindet zwei Kantsche Ideen mit dem modernen Relativismus, nämlich die Idee, daß wir die uns bekannte Welt mit Hilfe unserer Begriffe herstellen, und die, daß wir eine von uns unabhängige Welt durch unsere Erkenntnis nicht erreichen können.“ (Hans Albert 1996, S. 14 f) Der in den Sozialwissenschaften gegenwärtig zu beobachtende cultural turn kann als Ausdruck des von Hans Albert beklagten modernen Relativismus verstanden werden, zumindest dann, wenn sich der darauf berufende kultursoziologische Ansatz in deutlicher Frontstellung zum naturalistischen Theorieverständnis positioniert (vgl. Reckwitz 2000, Kap. 1, und die dort angegebene umfangreiche Literatur). Dieses in der Geschichte der Sozialwissenschaften nicht unbedingt neue Bemühen um Abgrenzung auf der Grundlage einer dualistischen Methodologie ist in der aktuellen Variante auch als Abwehrhaltung gegenüber wahrgenommenen naturalistischen Übergriffen, insbesondere auf den Gebieten der soziobiologischen Erklärung menschlichen Verhaltens, der neurowissenschaftlichen Erforschung des menschlichen Geistes und der Simulation von geistanalogen Steuerungsleistungen auf algorithmisch-kybernetischer Grundlage von der Künstlichen Intelligenz über Künstliches Leben bis hin zu Künstlichen Gesellschaften, -

-

New Arguments in Evolutionary Epistemology

NEW ARGUMENTS IN EVOLUTIONARY EPISTEMOLOGY GERHARD VOLLMER METAPHYSICAL IMPLICATIONS OF DARWINISM? Most implications of Darwinism are antimetaphysical. This is one of the reasons why Darwin’s theory was resisted and why it is still regarded as a scientific revolution. To be sure, it was not Darwin’s intention to become a revolutionary, but rather to solve interesting scientific problems. But his intention did not help him. In that respect, he may be likened to Nicolas Copernicus, Martin Luther, or Max Planck. Copernicus is characterized by Arthur Koestler as “the timid canon,” and Planck by Helge Kragh as “the reluctant revolutionary” 1. In a similar vein, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, writing about Werner Heisenberg, submits “that only the conservative can be a revolutionary” 2. Metaphysical or not, there is no doubt that Darwin’s theory has philo- sophical consequences. Some of these consequences refer to epistemology. Darwin himself was well aware of this. Already in 1838, he wrote in his notebook M: “Plato says in his Phaedo that our ‘necessary ideas’ arise from the preexistence of the soul, are not derived from experience—read mon- keys for pre-existence” 3. Even in this short note it becomes plain that Darwin replaces a metaphysical concept, preexistence, by a biological one, monkeys as man’s predecessors. Whether our ideas remain “necessary” in that move is another interesting problem. Cognition takes place in our heads. From the signals flowing from our sense organs our brain builds a picture of the world up to a whole world view. We construe the world as three-dimensional, ordered and directed in time, regular, even structured by laws of nature, causally connected. -

„Natürliche Einheit Des Wissens“? Von Der Metaphysik Als Wissenschaft Zur Metaphysischen Naturwissenschaft

Einheit des Selbstbewußtseins oder „natürliche Einheit des Wissens“? Von der Metaphysik als Wissenschaft zur metaphysischen Naturwissenschaft. Von der Philosophischen Fakultät der Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover zur Erlangung des Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von Christiane Müller, geboren am 14.04.1971 in Hannover 2013 Referent: Prof. Dr. Günther Mensching Korreferentin: Apl. Prof. Dr. Myriam Gerhard Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 19. April 2013 Abstract In dieser Arbeit wird die Frage thematisiert, welche ursprüngliche Einheit der Erkenntnis besser geeignet ist die Existenz wissenschaftlicher Objektivität zu begründen: Die Einheit eines transzendentalen Selbstbewußtseins oder eine ontologische Welteinheit. Das Interesse an dieser formalen Frage ist dabei vor allem durch die Konsequenzen für eine objektive Bestimmung des Menschen motiviert, die aus der jeweiligen Einheitsvorstellung resultieren. Um diesen Zusammenhang darzustellen, wird die Transzendentalphilosophie Immanuel Kants mit verschiedenen Ansätzen verglichen, die sich alle unter dem Begriff „metaphysische Naturwissenschaft“ zusammenfassen lassen, es handelt sich dabei um den Monismus Ernst Haeckels, die Evolutionäre Erkenntnistheorie von Konrad Lorenz, Gerhard Vollmer und anderen sowie die Soziobiologie und ihren jüngsten Ableger, die Evolutionspsychologie. Anhand der berühmten vier Fragen Kants: „Was kann ich wissen?“, „Was soll ich tun?“, „Was darf ich hoffen?“ und „Was ist der Mensch?“ gliedert sich eine Untersuchung, die am Ende aufzeigen wird, daß die vermeintlich moderneren Autoren keine „Revision der Transzendentalphilosophie“ (Vollmer) im „Lichte der gegenwärtigen Biologie“ (Lorenz) vollziehen, sondern tatsächlich bloß hinter den von Kant im 18. Jahrhundert erreichten Stand in der Erkenntnistheorie zurückfallen und damit letztlich einem „Menschenbild“ Vorschub leisten, das in seiner Willkürlichkeit und Relativität einen angestrebten „biologisch untermauerten Humanismus“ (Pinker) ad absurdum führt. -

Philosophy of Science in Germany, 1992–2012: Survey-Based Overview and Quantitative Analysis

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by RERO DOC Digital Library J Gen Philos Sci (2014) 45:71–160 DOI 10.1007/s10838-014-9270-8 REPORT Philosophy of Science in Germany, 1992–2012: Survey-Based Overview and Quantitative Analysis Matthias Unterhuber • Alexander Gebharter • Gerhard Schurz Published online: 9 November 2014 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 Abstract An overview of the German philosophy of science community is given for the years 1992–2012, based on a survey in which 159 philosophers of science in Germany par- ticipated. To this end, the institutional background of the German philosophy of science community is examined in terms of journals, centers, and associations. Furthermore, a quali- tative description and a quantitative analysis of our survey results are presented. Quantitative estimates are given for: (a) academic positions, (b) research foci, (c) philosophers’ of science most important publications, and (d) externally funded projects, where for (c) all survey participants had indicated their five most important publications in philosophy of science. In addition, the survey results for (a)–(c) are also qualitatively described, as they are interesting in their own right. With respect to (a), we estimated the gender distribution among academic positions. Concerning (c), we quantified philosophers’ of science preference for (i) journals and publishers, (ii) publication format, (iii) language, and (iv) coauthorship for their most important publications. With regard to research projects, we determined their (i) prevalence, (ii) length, and (iii) trend (an increase in number?) as well as their most frequent (iv) research foci and (v) funding organizations. -

A Defence of Non-Adaptationist Evolutionary Epistemology

Evolution, Knowledge, and Reality: A Defence of Non-Adaptationist Evolutionary Epistemology. Marta Facoetti 5595657 Master Thesis in History and Philosophy of Science Utrecht University, The Netherlands Supervisor: dr. Niels van Miltenburg Second Reviewer: dr. Jesse Mulder 1 “We cannot look around our corner…” Nietzsche, F. The Gay Science. Aphorism 374 2 Table of contents Acknowledgments 4 Preface 5 1. Introduction 8 2. State of the debate 16 2.1. Two theories of biological evolution ............................................................................ 17 2.2. Adaptationist approaches to EE .................................................................................... 21 2.3. Non-adaptationist approaches to EE ............................................................................. 25 2.3.1. Common-sense realism: between functional realism, internal realism, and non- realism .............................................................................................................................. 26 2.3.2. Complete Constructivist Evolutionary Epistemology (CCEE) .............................. 32 2.4. Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 39 3. Two reasons for preferring non-adaptationist approaches over adaptationist ones 43 3.1. The redundancy of hypothetical realism ....................................................................... 45 3.2. A question of epistemic circularity .............................................................................. -

Natural Organism, Artificial Organism, and Their Brains List of Participants

Natural Organism, Artificial Organism, and Their Brains List of Participants with Fields of Research Emilio Bizzi Nicolas Franceschini Massachusetts Institute of Technology CNRS/L.N.B. Department of Brain Cognitive Sciences 31, Ch. J. Aiguier 77 Massachusetts Avenue F-13402 Marseille Cedex 20 Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 USA Insect visuo-motor control; visually guided naviga Motor control; motor learning; formation of in tion; active vision; electrophysiology (neuroanat ternal models; motor cortex; spinal cord; modular omy/behavior); biology-derived robots; feedback organization of the motor system from robots to biology Neil Burgess Joaquin M. Fuster University College London Neuropsychiatric Institute Department of Anatomy Department of Psychiatry Gower Street 760 Westwood Plaza London, WC1E 6BT UK Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA Hippocampus; representation of space; navigation; Memory; frontal lobe; primates; cortex networks; neural networks; robots; rats; humans neurons; computational modeling; imaging Wolfgang Buschlinger Alfred Gierer TU Braunschweig MPI für Entwicklungsbiologie Seminar für Philosophie Spemannstr. 35 Geysostr. 7 D-72076 Tübingen D-38106 Braunschweig Pattern formation; axonal guidance in neural devel Philosophy of mathematics; artificial intelligence; opment; philosophy and history of science epistemology; philosophy of mind Mike Kilgard Hoik Cruse University of California Universität Bielefeld San Francisco Fakultät für Biologie Department of Otolaryngology Abt. Biologische Kybernetik Box 0732 Postfach 100131 513 Parnassus -

Radical Constructivism and Evolutionary Epistemology

Like cats and dogs: Radical constructivism and evolutionary epistemology Alexander Riegler Centrum Leo Apostel Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium, [email protected] Abstract I identify two similarities between evolutionary epistemology (EE) and radical constructivism (RC): (1) They were founded primarily by biologists and (2) their respective claims can be related to Kant. Despite this fact there seems to be an abyss between them. I present an attempt to reconcile this gap and characterize EE as the approach that focuses on external behaviour, while RC emphasizes the perspective from within. The central concept of hypothetical realism is criticized as unnecessarily narrowing down the scope of EE. Finally, methodological and philosophical conclusions are drawn. 1. INTRODUCTION In 1912, philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote: “There is no logical impossibility in the supposition that the whole of life is a dream, in which we ourselves create all the objects that come before us. But although this is not logically impossible, there is no reason whatever to suppose that it is true” (Russell, 1912: 35). Almost 90 years later, neurophysiologist Rudolfo Llin´as seemed to contradict Russell’s view. He argued that the mind is primarily a self- activating system, “one whose organization is geared toward the generation of intrinsic images” (Llin´as, 2001: 57) and this makes us “dreaming machines that construct virtual models” (Llin´as, 2001: 94). In some sense these statements could be considered the respective epistemo- logical mottos of evolutionary epistemology (EE)1 and radical constructivism 1 In the present context EE refers to evolutionary epistemology of mechanisms rather than evolutionary epistemology of theories—the classical distinction proposed by Michael Bradie (1986). -

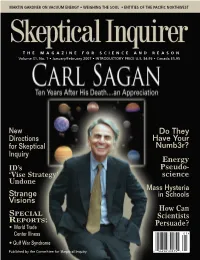

Do They Have Your Numb3r? Strange Visions

SI J-F 07 Cover V1 11/13/06 12:32 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON VACUUM ENERGY • WEIGHING THE SOUL • ENTITIES OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST THE MAGAZINE FOR SCIENCE AND REASON Volume 31, No. 1 • January/February 2007 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. $4.95 • Canada $5.95 New Do They Directions Have Your for Skeptical Numb3r? Inquiry Energy ID’s Pseudo- ‘Vise Strategy’ science Undone Mass Hysteria Strange in Schools Visions How Can SPECIAL Scientists REPORTS: Persuade? • World Trade Center Illness 01> • Gulf War Syndrome Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry 0556698 80575 SI J-F 2007 pgs 11/13/06 11:24 AM Page 2 THE COMMITTEE FOR SKEPTICAL INQUIRY AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY–TRANSNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO) AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, University at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto and Sciences, Professor of Philosophy and Robert L. Park, professor of physics, Univ. of Maryland Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Oregon Professor of Law, University of Miami John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist, Harvard England Journal of Medicine David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Columbia Univ. executive director CICAP, Italy consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human under- Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. -

Annals of the History and Philosophy of Biology

he name DGGTB (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Deutsche Gesellschaft für Theorie der Biologie; German Society for the History and Philosophy of BioT logy) refl ects recent history as well as German traditi- Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie on. The Society is a relatively late addition to a series of German societies of science and medicine that began with the „Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Medizin und der Naturwissenschaften“, Annals of the History founded in 1910 by Leipzig University‘s Karl Sudhoff (1853-1938), who wrote: „We want to establish a ‚German‘ society in order to gather Ger- and Philosophy of Biology man-speaking historians together in our special disciplines so that they form the core of an international society…“. Yet Sudhoff, at this Volume 11 (2006) time of burgeoning academic internationalism, was „quite willing“ to accommodate the wishes of a number of founding members and formerly Jahrbuch für „drop the word German in the title of the Society and have it merge Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie with an international society“. The founding and naming of the Society at that time derived from a specifi c set of histori- cal circumstances, and the same was true some 80 years later when in 1991, in the wake of German reunifi cation, the „Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie“ was founded. From the start, the Society has been committed to bringing stu- dies in the history and philosophy of biology to a wide audience, using for this purpose its Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie. Parallel to the Jahrbuch, the Verhandlungen zur Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie has become the by now traditional medi- (2006) 11 Vol. -

Gott Und Die Welt. Atheismus, Metaphysik, Evolution

Prof. Dr. Dr. Gerhard Vollmer (Neuburg) Gott und die Welt Atheismus, Metaphysik, Evolution 1. Atheismus die Existenz (eines) Gottes in der Regel Der Atheist glaubt nicht an Gott. Das kann bejaht. Gibt es nach meiner Überzeugung unterschiedliche Gründe haben. Entweder nur einen Gott, so bin ich Monotheist; gibt hat er noch nie etwas von Gott gehört; es mehrere, so bin ich Polytheist. das ist sicher nur selten der Fall. Oder er Im Folgenden gehen wir davon aus, dass ist der Meinung, das Wort ‚Gott’ habe es möglich ist, dem Wort ‚Gott’ eine inter- überhaupt keine mitteilbare Bedeutung, subjektiv annehmbare Bedeutung zu ge- sodass alle Sätze, in denen dieses Wort ben. Danach ist (ein) Gott ein höheres oder wesentlich vorkommt, unverständlich oder höchstes personales Wesen, Urgrund, sinnlos seien. Oder er billigt dem Wort Schöpfer und Erhalter der Welt, mäch- ‚Gott’ durchaus eine Bedeutung zu, ist aber tig, klug, gut, gerecht. In der Regel hat er der Meinung, dass es einen solchen Gott noch viele weitere Eigenschaften, die aber oder Götter nicht gebe. Er wird deshalb nicht in allen Religionen dieselben sein auch keine Anstrengungen unternehmen, müssen. darüber etwas herauszufinden. Selbst die genannten Eigenschaften kom- Der Agnostiker dagegen lässt die Frage men nicht allen Göttern zu. So haben die nach der Existenz (eines) Gottes bewusst altgriechischen Götter, so mächtig sie sein offen. Er traut sich nicht zu, über die Exis- mögen, doch auch sehr menschliche und tenz und die Eigenschaften Gottes Aus- durchaus endliche Eigenschaften: Sie ver- sagen zu machen, die sich durch Argu- lieben sich, sind eifersüchtig, parteiisch, mente stützen ließen. -

Introduction to the Proceedings of the Workshop" Natural Organisms

Introduction to the Proceedings of the Workshop “Natural Organisms, Artificial Organisms, and Their Brains” at the Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Forschung (ZiF) der Universität Bielefeld, March 8-12,1998 Hennig Stieve Institut für Biologie II, RWTH Aachen, D-52074 Aachen, Germany Z. Naturforsch. 53c, 439-444 (1998); received May 18, 1998 There have been many meetings in recent years bingen, Hans Flohr, Bremen, Hans-Joachim on “Brain and Computer” topics under a number Freund, Düsseldorf, Karl Georg Götz, Tübingen, of different aspects. Although it is not my own Klaus Hausen, Köln, Wolfgang Prinz, München, field of experimental work, I have been discussing Helge Ritter, Bielefeld, Jürgen Schnakenberg, this subject with brain- and computer scientists, ro Aachen, Werner von Seelen, Bochum, Jan-Dieter boticists, psychologists, and scholars of the human Spalink, Durham, Gerhard Vollmer, Braun ities for several years (Stieve, 1995). The confer schweig and Reto Weiler, Osnabrück. ences about mind and brain which I attended or At first I tried to organize a one year research read about were often characterized by a lack of group at the Zentrum für interdisziplinäre true discussion, i.e. disputation of differing argu Forschung (ZiF) in Bielefeld. But this seemed not ments, and did not seem to have an impact on on to work. Later I became convinced that an intense going research. People presented their data, find workshop would be a better frame for such a dis ings and opinions in monologues without seriously cussion. discussing their grounding and the reasons for the For such a workshop it seemed necessary to disagreements with others.