Japan Studies Review Volume Five 2001 Contents Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia No. 27 Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia

ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 27 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA Editor-in-Chief Board of Advisory Editors MARIA ROMAN S£AWIÑSKI NGUYEN QUANG THUAN KENNETH OLENIK Subject Editor ABDULRAHMAN AL-SALIMI OLGA BARBASIEWICZ JOLANTA SIERAKOWSKA-DYNDO BOGDAN SK£ADANEK Statistical Editor LEE MING-HUEI MARTA LUTY-MICHALAK ZHANG HAIPENG Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures Polish Academy of Sciences ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 27 ASKON Publishers Warsaw 2014 Secretary Nicolas Levi English Text Consultant James Todd © Copyright by Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 2014 Printed in Poland This edition prepared, set and published by Wydawnictwo Naukowe ASKON Sp. z o.o. Stawki 3/1, 00193 Warszawa tel./fax: (+48) 22 635 99 37 www.askon.waw.pl [email protected] PL ISSN 08606102 ISBN 978837452080–5 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA is abstracted in The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Index Copernicus To the memory of Professor Karin Tomala Whom we lost for ever Contents ARTICLES OLGA BARBASIEWICZ, The Cooperation of Jacob Schiff and Takahashi Korekiyo Regarding the Financial Support for the War with Russia (19041905). Analysis of Schiff and Takahashis Private Correspondence and Diaries ............................................................................ 9 KAROLINA BROMA-SMENDA, Enjo-kôsai (compensated dating) in Contemporary Japanese Society as Seen through the Lens of the Play Call Me Komachi ....................................................................... -

Back Roads to Far Towns, 15

■ ■— M •• ■ . *:T /- :A A- BACK ROADS gflTif;::,: TO FAR TOWNS i Basko’s 0 K U-NO-HOS 0 MICHI - i ■ \ ’ 1 ■v j> - iS§ : i1 if £i mf■ - •V ■;;! $SjK A . ; *4. I - ■- ■ ■■ -i ■ :: Y& 0 ■ 1A with a translation and. notes by - '■-'A--- $8? CID CORMAN and KAMAIKE SUSUMU $ 1 ;vr-: m \ I mm5 is f i f BACK ROADS TO FAR TOWNS Bashd’s 0 K U-NO -HO SO MICHI with a translation and notes by CID CORMAN and KAMAIKE SUSUMU • • • • A Mushinsha Limited Book Published by Grossman Publishers : Distributed in Japan by Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc. Suido 1-chome, 2-6, Bunkyo-ku, > Tokyo, Japan i First published in The United States of America in 1968 by Grossman Publishers Inc. 125 A East 19th Street New York, New York 10003 ; Designed and produced by Mushinsha Limited, IRM/Rosei Bldg., 4, Higashi Azabu 1-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Copyright, 1968, by Cid ! Corman. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan. First edition, 1968 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 67-26108 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction, 7 Translators’ Preface, 11 Pronunciation Guide, 12 Back Roads to Far Towns, 15 Notes, 157 Map, 174 : m im mi t INTRODUCTION early one spring morning in 1689 basho Ac companied by his friend and disciple Sora set forth from Edo (old Tokyo) on the long nine-month journey which was to take them through the backlands and highlands north of the capital and then west to the Japan Sea coast and along it until they turned inland again towards Lake Biwa (near Kyoto). -

Volume XI Number 2 CONTENTS Fall 2003

Volume XI Number 2 CONTENTS Fall 2003 From the Editors' Desk 編纂者から 1 EMJ Renewals, Call for Proposals, EMJNet at the AAS 2004 (with abstracts of presentations) Articles 論文 Collaboration In Haikai: Chōmu, Buson, Issa Collaboration In Haikai: Chōmu, Buson, Issa: An Introduction Cheryl Crowley 3 Collaboration in the "Back to Bashō" Movement: The Susuki Mitsu Sequence of Buson's Yahantei School Cheryl Crowley 5 Collaboration of Buson and Kitō in Their Cultural Production Toshiko Yokota 15 The Evening Banter of Two Tanu-ki: Reading the Tobi Hiyoro Sequence Scot Hislop 22 Collaborating with the Ancients: Issues of Collaboration and Canonization in the Illustrated Biography of Master Bashō Scott A. Lineberger 32 Editors Philip C. Brown Ohio State University Lawrence Marceau University of Delaware Editorial Board Sumie Jones Indiana University Ronald Toby University of Illinois For subscription information, please see end page. The editors welcome preliminary inquiries about manuscripts for publication in Early Modern Japan. Please send queries to Philip Brown, Early Modern Japan, Department of History, 230 West 17th Avenue, Colmbus, OH 43210 USA or, via e-mail to [email protected]. All scholarly articles are sent to referees for review. Books for review and inquiries regarding book reviews should be sent to Law- rence Marceau, Review Editor, Early Modern Japan, Foreign Languages & Lit- eratures, Smith Hall 326, University of Deleware, Newark, DE 19716-2550. E-mail correspondence may be sent to [email protected]. Subscribers wishing to review books are encouraged to specify their interests on the subscriber information form at the end of this volume. The Early Modern Japan Network maintains a web site at http://emjnet.history.ohio-state.edu/. -

Basho's Haikus

Basho¯’s Haiku Basho¯’s Haiku Selected Poems by Matsuo Basho¯ Matsuo Basho¯ Translated by, annotated, and with an Introduction by David Landis Barnhill STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Matsuo Basho¯, 1644–1694. [Poems. English. Selections] Basho¯’s haiku : selected poems by Matsuo Basho¯ / translated by David Landis Barnhill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6165-3 — 0-7914-6166-1 1. Haiku—Translations into English. 2. Japanese poetry—Edo period, 1600–1868—Translations into English. I. Barnhill, David Landis. II. Title. PL794.4.A227 2004 891.6’132—dc22 2004005954 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 for Phyllis Jean Schuit spruce fir trail up through endless mist into White Pass sky Contents Preface ix Selected Chronology of the Life of Matsuo Basho¯ xi Introduction: The Haiku Poetry of Matsuo Basho¯ 1 Translation of the Hokku 19 Notes 155 Major Nature Images in Basho¯’s Hokku 269 Glossary 279 Bibliography 283 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Translation 287 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Japanese 311 Index of Names 329 vii Preface “You know, Basho¯ is almost too appealing.” I remember this remark, made quietly, offhand, during a graduate seminar on haiku poetry. -

Representations of Travel in Medieval Japan by Kendra D. Strand A

Aesthetics of Space: Representations of Travel in Medieval Japan by Kendra D. Strand A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Asian Languages and Cultures) in The University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Emerita Professor Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen, Chair Associate Professor Kevin Gray Carr Professor Ken K. Ito, University of Hawai‘i Manoa Associate Professor Jonathan E. Zwicker © Kendra D. Strand 2015 Dedication To Gregory, whose adventurous spirit has made this work possible, and to Emma, whose good humor has made it a joy. ii Acknowledgements Kind regards are due to a great many people I have encountered throughout my graduate career, but to my advisors in particular. Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen has offered her wisdom and support unfalteringly over the years. Under her guidance, I have begun to learn the complexities in the spare words of medieval Japanese poetry, and more importantly to appreciate the rich silences in the spaces between those words. I only hope that I can some day attain the subtlety and dexterity with which she is able to do so. Ken Ito and Jonathan Zwicker have encouraged me to think about Japanese literature and to develop my voice in ways that would never have been possible otherwise, and Kevin Carr has always been incredibly generous with his time and knowledge in discussing visual cultural materials of medieval Japan. I am indebted to them for their patience, their attention, and for initiating me into their respective fields. I am grateful to all of the other professors and mentors with whom I have had the honor of working at the University of Michigan and elsewhere: Markus Nornes, Micah Auerback, Hitomi Tonomura, Leslie Pinkus, William Baxter, David Rolston, Miranda Brown, Laura Grande, Youngju Ryu, Christi Merrill, Celeste Brusati, Martin Powers, Mariko Okada, Keith Vincent, Catherine Ryu, Edith Sarra, Keller Kimbrough, Maggie Childs, and Dennis Washburn. -

Four Japanese Travel Diaries of the Middle Ages

FOUR JAPANESE TRAVEL DIARIES OF THE MIDDLE AGES Translated from the Japanese with NOTES by Herbert PJutschow and Hideichi Fukuda and INTRODUCfION by Herbert Plutschow East Asia Program Cornell University Ithaca, New York 14853 The CornellEast Asia Series is published by the Cornell University East Asia Program (distinctfromCornell University Press). We publish affordablypriced books on a variety of scholarly topics relating to East Asia as a service to the academic community and the general public. Standing orders, which provide for automatic notification and invoicing of each title in the series upon publication, are accepted. Ifafter review byinternal and externalreaders a manuscript isaccepted for publication, it ispublished on the basisof camera-ready copy provided by the volume author. Each author is thus responsible for any necessary copy-editingand for manuscript fo1·111atting.Address submission inquiries to CEAS Editorial Board, East Asia Program, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-7601. Number 25 in the Cornell East Asia Series Online edition copyright© 2007, print edition copyright© 1981 Herbert Plutschow & Hideichi Fukuda. All rights reserved ISSN 1050-2955 (for1nerly 8756-5293) ISBN-13 978-0-939657-25-4 / ISBN-to 0-939657-25-2 CAU'I'ION: Except for brief quotations in a review, no part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any for1n without per1nissionin writing from theauthor. Please address inquiries to Herbert Plutschow & Hideichi Fukuda in care of the EastAsia Program, CornellUniversity, 140 Uris Hall, Ithaca, -

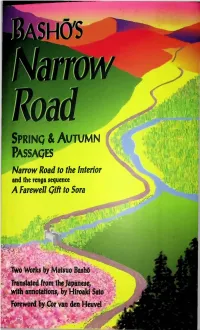

Spring &Autumn

Spring & Autumn Passages Narrow Road to the Interior and the renga sequence A Farewell Qift to Sora iV-y, . p^: Two Works by Matsuo BasM Translated from the Japanese, with annotations, by Hiroaki Sato Foreword by Cor van den Heuvel '-f BASHO'S NARROW ROAD i j i ; ! ! : : ! I THE ROCK SPRING COLLECTION OF JAPANESE LITERATURE ; BaSHO'S Narrow Road SPRINQ & AUTUMN PASSAQES Narrow Road to the Interior AND THE RENGA SEQUENCE A Farewell Gift to Sora TWO WORKS BY MATSUO BASHO TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE, WITH ANNOTATIONS, BY Hiroaki Sato FOREWORD BY Cor van den Heuvel STONE BRIDGE PRESS • Berkeley,, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O, Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www.stoncbridgc.com Cover design by Linda Thurston. Text design by Peter Goodman. Text copyright © 1996 by Hiroaki Sato. Signature of the author on front part-title page: “Basho.” Illustrations by Yosa Buson reproduced by permission of Itsuo Museum. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG1NG-1N-PUBL1 CATION DATA Matsuo, BashO, 1644-1694. [Oku no hosomichi. English] Basho’s Narrow road: spring and autumn passages: two works / by Matsuo Basho: translated from the Japanese, with annotations by Hiroaki Sato. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Narrow road to the interior and the renga sequence—A farewell gift to Sora. ISBN 1-880656-20-5 (pbk.) 1- Matsuo, Basho, 1644-1694—Journeys—Japan. -

Ready, Set, Nihongo!

nihongo-pro.com Issue 19 October 1, 2016 Ready, Set, NihonGO! ふくしまけん し ら か わ し わ た 私 し の 福島県 白河市 ま 町 ち わたし ふ く し ま けん し ら か わ し いま ・ わ 私 のふるさとは、福島県の白河市です。今やこのFUKUSHIMA”は た 私 し げ ん ぱ つ じ こ せ か いじ ゅう ゆうめい う こ き ょ う の 原発事故で、世界中で有名になってしまいましたが、生まれ故郷としての ふ く し ま しょうかい ふ 福島を紹介します。 ASAI Yukiko る わたし う こ う こ う そつぎょう まち く いま おお Nihongo-Pro Teacher 私 は生まれてから高校を卒業するまで、この町で暮らしました。今では大 さ しょうぎょうしせつ た なら まちなみ か なつ Asai-sensei teaches と きな商業施設が立ち並び、ずいぶん街並も変わりましたが、夏になると private lessons at all いちめんあおあお た ひろ ふうけい いま み levels except 《 一面青々とした田んぼが広がっている風景を今でも見ることができます。 6 introductory, as well し ら か わ し ちい こ み ね じ ょ う しろ ひがしにほんだいしんさい as JLPT N1 and N2 》 白河市には、小さいですが、小峰城という城があります。東日本大震災の preparation. She uses とき いしが き くず きょ ねん なつ かえ しゅうふくちゅう なか はい the direct method of 時に石垣が崩れてしまい、去年の夏に帰ったときは修復中で中に入ること teaching, with みなみ いち なづ な ん こ こ う え ん instruction and はできませんでした。その 南 に位置していることから名付けられた南湖公園は、 explanation in なん に ほ ん いちばんふる こ う え ん みずうみ まわ さくら き う わたし 何と日本で一番古い公園なんですよ! 湖 の周りに桜の木が植えてあり、 私 は Japanese as much as さくら け し き い ち ば ん す possible. ここの桜の景色が一番好きです。 し な い すこ はな ま つ お ば し ょ う は い く よ しらかわ せき ゆうめい また、市内から少し離れますが、松尾芭蕉が俳句を詠んだ「白河の関」も有名で ちか なつ な ん ど かよ や めん ふと ちぢ す。その近くに、ひと夏に何度も通ったおいしいラーメン屋があります。麺は太い縮 めん とくちょう れ麺、もちもちしているのが特徴です。 し ら か わ し まつ ねん い ち ど がつ かいさい ちょうちんまつ じ ん じ ゃ 白河市にはお祭りもあります。2年に一度9月に開催される「提灯祭り」は、神社 しゅっぱつ み こ し み っ か か ん ま ち ね ある じ ん じ ゃ もど かいがい す から出発した神輿が、三日間町を練り歩いて、また神社に戻ります。海外に住ん し ら か わ し み い こ ど も み こ し 白河市 でからはなかなか見に行けませんが、子供のころは神輿を Shirakawa City ひ ぱ ちょうない い せ い か ごえ 引っ張っていました。いろいろな町内の威勢のいい掛け声は、 (Continued on page 4) nihongo-pro.com 1 こみねじょう -

Learning with Waka Poetry: Transmission and Production Of

Learning with Waka Poetry: Transmission and Production of Social Knowledge and Cultural Memory in Premodern Japan Ariel G. Stilerman Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Ariel G. Stilerman All rights reserved ABSTRACT Learning with Waka Poetry: Transmission and Production of Knowledge and Cultural Memory in Premodern Japan Ariel G. Stilerman This dissertation argues that throughout premodern Japan, classical Japanese poetry (waka) served as a vehicle for the transmission of social knowledge, cultural memory, and specialized information. Waka was originally indispensable to private and public social interactions among aristocrats, but it came to play a diversity of functions for warriors, monks, farmers, merchants, and other social groups at each and every level of premodern society and over many centuries, particularly from the late Heian period (785- 1185) through the Edo period (1600-1868). To trace the changes in the social functions of waka, this dissertation explores several moments in the history of waka: the development of a pedagogy for waka in the poetic treatises of the Heian period; the reception of these works in anecdotal collections of the Kamakura period (1192-1333), particularly those geared towards warriors; the use of humorous waka (kyôka), in particular those with satiric and parodic intent, in Muromachi-period (1333-1467) narratives for commoners; and the use of waka as pedagogical instruments -

The Mumyosho of K a M 0 No Chomei and Its Significance

THE MUMYOSHO OF K A M 0 NO CHOMEI AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE IN JAPANESE LITERATURE by HILDA KATO Doktorand der Universitat Miinchen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFIIIMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of ASIAN STUDIES We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1964 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of • British Columbia,, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study, I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission* Department of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada ii Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the significance of Japanese theoretical writing on poetry of the Heian period (794 - 1192) (as manifested in the distinctive literary genre known as the karon) with special reference to the development of esthetic concepts in general and the influence of this kind of writing on the Japanese literature of later periods. An attempts is made to show through the presentation of one of the major works in this field, which is here translated into English, what factors were responsible for the distinctive characteristics of Japanese poetry. This kind of study has never been undertaken in English and no source material is available in translation; I therefore thought it best to make a start in this field-.with a complete translation of the Mumyosho by Kamo no Chomei, one of the most important Japanese theoretical works on poetry. -

Ties of Resentment, Drifting Clouds: Two Stories from Tsuga Teishō's Shigeshige Yawa

Ties of Resentment, Drifting Clouds: Two Stories from Tsuga Teishō’s Shigeshige yawa by Alicia Foley BA, College of William and Mary, 2003 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Asian Languages and Civilizations, Japanese 2011 This thesis entitled Ties of Resentment, Drifting Clouds: Two Stories from Tsuga Teishō’s Shigeshige yawa written by Alicia Foley Has been approved by the Department of Asian Languages and Civilizations ______________________________________________ Satoko Shimazaki, Thesis Chair _______________________________________________ Laurel Rasplica Rodd ________________________________________________ Keller Kimbrough The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Foley, Alicia (MA, Department of Asian Languages and Civilizations) Ties of Resentment, Drifting Clouds: Two Stories from Tsuga Teishō’s Shigeshige yawa Thesis directed by Satoko Shimazaki, Assistant Professor of Japanese Tsuga Teishō, a writer and intellectual from 18th century Japan, is known for his yomihon – complex adaptations of Chinese vernacular fiction. This thesis offers annotated translations of two tales from Teishō’s second collection of adaptations, Kokon kidan shigeshige yawa 古今 奇談繁野話 (Strange Tales Then and Now of a Thriving Field, 1766). The stories are titled: “Unkon unjō o katatsute hisashiki o chikau koto” 雲魂雲情を語て久しきを誓ふ話 (The Tale of Cloud Spirits Speaking of Their Clouded Feelings, and Making a Long-Term Promise) and “Nakatsugawa nyūdō yamabushizuka o tsukashimuru koto” 中津川入道山伏塚を築しむる話 (The Tale of How the Nakatsugawa Lay Priest had the Mountain Ascetic Mound Built). -

SAM HAMILL . * • I

-■? *• J f‘ m . r*0 ^ ■ •- <;*w k , <*•'/ • *. ‘: v-.r. s 1 ? \y* ^\\i ■v^Vk Vw>'>v■v-'iiv translated ; « * SAM HAMILL . * • i. 4 V* . vv- FPT $25.00 (Canada $38.00) he Essential Basho is the most complete single-volume collection of the writ Tings of one of the great luminaries of Asian literature. Basho (1644-1694)—who elevated the haiku to an art form of utter simplicity and intense spiritual beauty—is best known in the West as the author of Narrow Road to the Interior, a travel diary of linked prose and haiku that recounts his journey through the far northern provinces of Japan. Included here is a masterful trans lation of this celebrated work, along with three other less well-known but important works by Basho: Travelogue of Weather-Beaten Bones, The Knapsack Notebook, and Sarashina Travelogue. There is also a selection of over 250 of Basho’s finest haiku. In addition, the translator has provided an introduction detailing Basho’s life and work and an essay on the art of haiku. Praise for Sam Hamill’s translation of Basho’s Narrow Road to the Interior “In the spirit of Basho and all the poets before him, Hamill has given us some thing of lasting importance and beauty.” — Leza Lowitz, The Japan Times I ! E 1 . ; ? . T h c Essential B a s h o : > 1 ■ ALSO BY SAM HAMILL Published by Shambhala Publications The Essential Chuang Tzu, translated with J. P. Seaton 1998 The Spring of My Life and Selected Haiku, by Kobayashi Issa 1997 Only Companion: Japanese Poems of Love and Longing 1997 The Erotic Spirit: An Anthology of Poems of Sensuality, Love, and Longing 1996 River of Stars: Selected Poems ofYosano Alako, I translated with Keiko Matsui Gibson 1996 i ! M ■! : » THE ESSENTIAL BASHO smBSt&rJtI Matsuo Basho Translated from the Japanese by Sam Hamill SHAMBHALA Boston & London 1999 ' i Shambhala Publications, Inc.