Access Article In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Schools and Boards Using Etms - October 23, 2020

List of Schools and Boards Using eTMS - October 23, 2020 Board Name School Name Algoma DSB ADSB Virtual Secondary School Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB ALCDSB Summer School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre-Con Ed Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Nicholson Catholic College Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Theresa Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Paul Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Regiopolis/Notre-Dame Catholic High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Holy Cross Catholic Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB South Huron District High School Avon Maitland DSB Stratford Ctr For Employment and Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Wingham Employment And Learning NS Avon Maitland -

Toronto Regional Showcase 2017

Toronto Regional Showcase 2017 April 6, 7 and 8 Hart House Theatre University of Toronto Page 1 Welcomes you to the Regional Showcase of the 71st Annual Sears Ontario Drama Festival! Sears Canada is proud to sponsor this exceptional event and to celebrate remarkable achievements in the arts by talented students, such as those you will see on the stage this evening. These performances are a reflection of the dedicated and talented students and teachers in the drama programs of our Ontario high schools. The Sears Charitable Foundation is a registered Canadian charity focused on the development of children and youth in areas of both health and education. The health component is centered on raising awareness and providing funds for research and treatment for the fight against childhood cancer. The education component is centered on after-school programs and initiatives such as the Sears Ontario Drama Festival, which enrich young people’s lives and allow them to reach their full potential. Please consider making a donation and help us continue to provide meaningful experiences. Together, we can make a difference in the lives of young people. Visit www.searsfoundation.ca Page 2 Welcome... to the 71st Toronto Regional Showcase of the Sears Ontario Drama Festival. The nine productions that you will see during the three evenings of the Showcase represent outstanding achievement in high school theatre from the three Toronto District Festivals. The presentations are accompanied by public and private adjudications that expand the participating students’ -

7 Foundry Ave, Toronto, on M6H 3Z4, Canada

The Christine Cowern Team 7 Foundry Ave 416.291.7372 Toronto, ON ChristineCowernTeam.com HOODQ HIGHLIGHTS ELEMENTARY TRANSIT SAFETY SCHOOLS 9.7 8.5 8.5 HIGH PARKS CONVENIENCE SCHOOLS 8.1 10 8.5 PUBLIC SCHOOLS (ASSIGNED) Your neighbourhood is part of a community of Public Schools offering Elementary, Middle, and High School programming. See the closest Public Schools near you below: 6.2 Regal Road Junior Public School FRASER INSTITUTE about a 12 minute walk - 0.89 KM away Pre-Kindergarten, Kindergarten and Elementary 95 Regal Rd, Toronto, ON M6H 2J6, Canada The mission of Regal Road Public School is to strive for equity and excellence for all students in partnership with the community. Regal Road Public School is situated on the northeast corner of Davenport Road and Dufferin Street. It is a dynamic dual-track school with an enrolment of approximately 550 students. Our students represent diverse ethnocultural and family backgrounds. While two-thirds of the students speak English at home, over 45 language groups are represented. http://www.tdsb.on.ca... Address 95 Regal Rd, Toronto, ON M6H 2J6, Canada Language English Date Opened 01-09-1969 Grade Level Pre-Kindergarten, Kindergarten and Elementary School Code 5268 School Type Public Phone Number 416-393-1390 Rating Trend n/a School Board Toronto DSB School Number 479640 Grades Offered PK to 6 Most Recent Rank 1430 Additional Details French Immersion Most Recent Rating 6.2 School Board Number B66052 District Description Toronto and Area Regional Office Rank in the Most Recent n/a Five Years Fraser Institute School http://ontario.compareschoolrankings.org.. -

Government Series RG 2-219 Ministry of Education Private School Files

List of: Government Series RG 2-219 Ministry of Education private school files Reference File Item Title and Physical Description Date Ordering Information Code Code RG 2-219 1964-1968 1964-1968 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1969 1969 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1970 1970 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1971 1971 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1972 1972 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1971-1972 registrations O-Z [by geographical location] 1971 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1971-1972 registrations G-N [by geographical location] 1971 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1971-1972 registrations A-F and Toronto [by 1971 Item is located in RG 2-219, in geographical location] container B316521 1 file of textual records RG 2-219 1970-1971 registrations T-Z [by geographical location] 1970 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1970-1971 registrations M-S [by geographical location] 1970 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1970-1971 registrations A-L [by geographical location] 1970 Item is located in RG 2-219, in 1 file of textual records container B316521 RG 2-219 1969-1970 registrations -

Director's Bulletin

Validating our Mission/Vision September 25, 2006 IFITH Subjects: 1. MESSAGE TO ALL STAFF REGARDING TCDSB BUDGET 2. SAINTS OF THE TORONTO CATHOLIC DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD T 3. ANNUAL EDUCATION MASS H DIRECTOR’S E 4. CATEGORY UPGRADING FORM--revised BULLETIN 5. DEFERRED SALARY PLANS 2006-2007 - Management Employee Group - CUPE Local 1328 - OCT - CUPE Local 1280 In a school community 6. FALL CLEAN-UP AND TREE PLANTING & REGISTRATION FORM formed by Catholic 7. THE TEACHER & THE SOUL beliefs and traditions, our Mission is to 8. SCHOOL ANNIVERSARIES, OFFICIAL OPENINGS & BLESSINGS - St. Henry’s 25th Anniversary educate students - Our Lady of the Assumption’s 50th Anniversary to their full potential - St. Jane Frances Solemn Blessing & Official Opening 9. AWARDS, SCHOLARSHIP, BURSARIES & CONTESTS - Barry Diemert Staff Arts Award 10. EVENT NOTICES A Community of Faith - Carr’s Homecoming Football Game - MTCEF ‘Evening to Feed the Soul’ 11. SHARING OUR GOOD NEWS - Holy Name Catholic School & Cardinal Carter Academy for the Arts - Father John Redmond Catholic Secondary School With Heart in Charity 12. MEMORIALS 13. BIRTHS AND ADOPTIONS 14. CURRICULUM & ACCOUNTABILITY Anchored in Hope - Statistics Canada Learning Resources - Leadership Course in Race & Ethnic Relations Multiculturalism - Morley S. Wolfe Youth Book Competition - Art Ideas for the Classroom Workshop - TCDSB & OBEA Board Results - Human Rights & Race Relations Centre Essay Competition 15. CSAC NEWS - Catholic School Advisory Council Conference 16 BENEFITS CORNER - Claims for orthotics, -

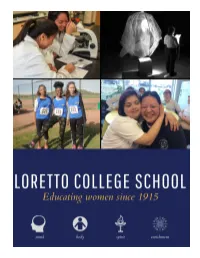

Vision of a Loretto Student

Join the Legacy of the Loretto Sisters FROM THE EARLIEST YEARS of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary (IBVM), our founder, Mary Ward, and her companions engaged in the works of education, particularly education of women—no easy feat in the 1600s! The five Loretto Sisters who first came to Toronto from Ireland in 1847 opened the first Loretto School in North America with nine initial boarders. The traditional “free school” for the children of St. Paul’s Parish followed soon after. The Loretto Sisters became “There is no such difference between known for excellence in education and went on to establish men and women that women private schools in various areas of Ontario. Schools were may not do great things… established in Toronto, Guelph, Niagara Falls, Hamilton, and women in time to come will do much.” Lindsay and in Sedley, Saskatchewan. ~ Mary Ward After the Separate School Act of 1863, the Loretto Sisters went out daily to teach in a variety of urban and rural Separate Schools throughout Ontario and Saskatchewan. TODAY, the IBVM ministry of education continues to evolve in response to the needs of the times. Loretto Sisters continue to be educators in very diverse settings; these include: Education for justice, peace and integrity of creation, Educating for personal growth and leadership through workshops and presentations in various community and parish settings, Serving the Catholic Community as Diocesan Directors of Religious Education, Teaching in University and Seminary settings, Educating for Christian formation through RCIA and scripture study, Teaching English as a second language to refugees and newcomers to Canada LORETTO COLLEGE SCHOOL is very proud to be part of this over 400 year educational legacy and are proud to be partnered in sisterhood with over 100 schools worldwide. -

First Canadian National Missionary Exhibition and Convention to Be

First Canadian National Souven ir Handbook Missionary Exhibition 'rice 10( liiiinniminimtmiTFmTreg ^« mmmmimfm^mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm L^ ii\rifi*r '^dWNWSNP' w ^^^^KP^gfwmw m W'SHHWi^Br w < y z s Q i $> ! ^ mat z <j un ^ ** 1 ^ 1 • ** 5 « O Wlu\ X H W 5 ' iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiini^ H O (7 55 ^o ^ o §)^^^[^t^t^t^^^t^^^^^ Compliments of ®f)e 3fastttute of Wi)t Plesseb #trgm jffflarp tn America Loretto Abbey Toronto, Ontario Loretto College Toronto, Ontario Loretto College School Toronto, Ontario Loretto Secretarial College Toronto, Ontario St. Cecilia's Convent Toronto, Ontario Loretto Academy Niagara Falls, Ontario Loretto Academy Stratford, Ontario Loretto Academy Guelph, Ontario Loretto Academy Hamilton, Ontario St. Theresa's Convent Port Colborne, Ontario Loretto Academy, East 65th St Chicago, Illinois Loretto Convent, Stewart Avenue . Chicago, Illinois Loretto High School, Stewart Ave. Chicago, Dlinois St. Bride's Convent, South Shore Dr. Chicago, Illinois Loretto Academy Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan 1 Loretto Academy • * Sedley, Saskatchewan Loretto Convent . Regina, Saskatchewan Loretto High School Regina, Saskatchewan hrwr^rygflriwrrwryw>ifrwr^ —I— Save Money ON OUTDOOR DISPLAY Use De Luxe Service SPECIAL SIGN WORK All work by professionals. Quotations given freely. CONVENTION DISPLAYS All facilities for quick service for exhibitors and other special displays. THE COTTON BANNERS ROYAL YORK is Glad to be De Luxe Advertising Your Host Co., Ltd. 340 Dufferin St., Toronto. LL. 6682 It is our ambition during these dif- The only Independent Poster ficult times to maintain our usual Company in Canada high standard of service and keep our good friends, so that when this conflict is over and business be- comes more nearly normal they will think of us in a kindly way. -

List of Schools and Boards Using Etms - July 16, 2019

List of Schools and Boards Using eTMS - July 16, 2019 Board Name School Name Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB ALCDSB Summer School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre-Con Ed Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Nicholson Catholic College Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Theresa Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Paul Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Regiopolis/Notre-Dame Catholic High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Holy Cross Catholic Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB South Huron District High School Avon Maitland DSB Stratford Ctr For Employment and Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Wingham Employment And Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Seaforth DHS Night School - CLOSED -

Etobicoke & York RTO-ERO District 22 Tea & Trivia Silent Auction

50th Anniversary 45th Anniversary Etobicoke & York RTO-ERO District 22 Tea & Trivia Silent Auction Catalogue Wednesday April 11, 2018 Markland Wood Golf Club Registration: 12:15 p.m. Bidding Closes: 3:00 p.m. Reserved Bids in Place 50th Anniversary Celebration Tea & Trivia Organizing Committee Maryanne Chard Marilyn Jones Sharon Kular Claudia Mang Joel Nasimok Rose Ramundi Mary Jean Ricci We would like to thank the following artists who graciously donated their works for the Silent Auction to benefit the TCDSB and TDSB Breakfast Programs and the RTO-ERO Foundation. (Listed Alphabetically) Joyce Carter Norma Clarke Donna Duplak Carol Howe Elizabeth Jay Barbara Laplante Claudia Mang Romana Marconi Jax Nasimok Jane Shaw Judi Waymark ____________________________________ An art piece by Ina Puchala donated by Karl Sprogis An art piece by Jean Townsend donated by Linda Rodegard Luncheon Menu for 50th Anniversary Tea and Trivia Event Wednesday April 11, 2018 Assorted Tea Sandwiches An assortment of wraps and tea sandwiches (white and whole wheat) Egg and tuna salad, cucumber and cream cheese, Ham and cheddar cheese Domestic cheese board served with crackers and cheese biscuits Vegetable crudités and dip Fresh fruit platter House baked cookies, lemon squares, and decadent brownies Regular and decaffeinated coffee and tea On-site Bidding Procedures: 1. Registration will open at 12:15 p.m. 2. Bidding Sheets will be in front of each piece of art. 3. Reserved bids are in place. 4. Bidding will proceed in increments of $5.00. 5. Bidding will continue throughout the luncheon and the trivia game. 6. Bidding will close at 3 p.m. -

68 Harvard Ave 416.788.1823 Toronto, on Kimkehoe.Com HOODQ HIGHLIGHTS

Kim Kehoe 68 Harvard Ave 416.788.1823 Toronto, ON kimkehoe.com HOODQ HIGHLIGHTS ELEMENTARY TRANSIT SAFETY SCHOOLS HIGH PARKS CONVENIENCE SCHOOLS PUBLIC SCHOOLS (ASSIGNED) Your neighbourhood is part of a community of Public Schools offering Elementary, Middle, and High School programming. See the closest Public Schools near you below: Parkdale Junior and Senior Public School about a 10 minute walk - 0.75 KM away Pre-Kindergarten, Kindergarten, Elementary and Middle 78 Seaforth Ave, Toronto, ON M6K 3L2, Canada Parkdale Public School, commonly known as "the jewel of the south" is proud to be an inner city model school. The school works in partnership with the Parkdale Community Centre, the George Brown College Childcare Centre, the Parkdale Parenting Centre and the International Language Program to ensure that our students develop strong literacy and numeracy skills while placing an emphasis on critical thinking, character development and global citizenship. We focus on cross-curricular planning with curriculum that is culturally relevant in order for our students to develop the knowledge, skills and values they need to become responsible members of our democratic society. http://www.tdsb.on.ca... Address 78 Seaforth Ave, Toronto, ON M6K 3L2, Canada Language English Date Opened 01-09-1969 Grade Level Pre-Kindergarten, Kindergarten, Elementary and Middle School Type Public Phone Number 416-393-1280 School Board Toronto DSB School Number 434140 Grades Offered PK to 8 Most Recent Rank 2904 Most Recent Rating 2.8 School Board Number B66052 District Description Toronto and Area Regional Office Rank in the Most Recent n/a Five Years Fraser Institute School http://ontario.compareschoolrankings.org.. -

1969/70 5 /'/' Date= OA# 848 Dri? ’ \,’ Y,,,Mber 1, 1969

/ I’ A= UW T= UW - Student Statistical Informatio n 1969/70 5 /'/' Date= OA# 848 drI? ’ \,’ Y,,,mber 1, 1969 UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO REPORT OF THE REGISTRAR TO THE SENATE AND BOARD OF GOVERNORS I am pleased to submit statistical information for the University of Waterloo and its Federated and Affiliated Institutions. The forms used are as follows: TABLE NO. 1 - DISTRIBUTION OF TOTAL ENROLMENT TABLE NO. 2 - UNDERGRADUATE ENROLMENT IN REGULAR HONOURS AND GENERAL PROGRAMMES TABLE NO. 3 - BASIS FOR ADMISSION TO YEAR I TABLE NO. 4 - DISTRIBUTION OF FIRST YEAR ENROLMENT BY SCHOOLS TABLE NO. 5 - RELIGIOUS DENOMINATIONS OF STUDENTS TABLE NO. 6 - DISTRIBUTION OF STUDENT BY YEAR OF BIRTH TABLE NO. 7 - MARRIED STUDENT INFORMATION (ON & OFF CAMPUS) TABLE NO. 8 - GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF STUDENTS TABLENO. - STUDENT AID TABLE NO.10 - DEGREES GRANTED 1960-69 C.T. Boyes, ' REGISTRAR. i , ~PERATIONQ ANALYSIS 1_ __-.-- December 1, 1969. Table No. 1 Page 1 of 6 UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO DISTRIBUTION OF TOTAL ENROLMENT UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS FACULTY AND PROGRAMME FULL-TIME STUDENTS PT. TIME OTHERS ALL FAC. STUDENTS STUDENTS TOTAL I II III IV ALL M. F. M. F. M. F. M. F. M. F. M. F. M. F. M. F. FACULTY OF ARTS University - General 475 380 168 145 132 78 775 603 94 132 869 735 Honours 113 104 85 43 60 24 258 171 6 8 264 179 Special Prog. 52 50 21 9 73 59 St. Jerome's - General 71 42 33 15 31 23 135 80 25 39 160 119 Honours 24 13 18 11 12 6 54 30 1 55 30 Special Prog. -

Bishop Marrocco/Thomas Merton Catholic Marshall Mcluhan Catholic Secondary School

TDCSB-Calendr09:Layout 1 12/5/08 1:56 PM Page 1 TDCSB-Calendr09:Layout 112/5/081:56PMPage2 Design: Lynn Stanley, Graphic Directions Message from the Director of Education Dear Toronto Catholic District School Board Student: Welcome! Secondary school is an important and exciting stage of your life. You will be faced with choices about what you will study and learn how to lay a strong foundation for your life’s pursuits after high school. This Program and Course Calendar provides important information to assist you and your parents to make informed choices to meet your individual and academic needs as well as interests in support of your future goals. The Toronto Catholic District School Board is committed to meeting the needs of all students. We continue to offer innovative and creative programs; supports and pathways that will help take you toward graduation and your chosen path. As a Catholic school board, we are a hope filled community and it is with hope that we continue to grow and move forward to educate our students to be citizens of the world. Social justice, human rights and the preservation of our environment are only a few examples of our obligations that flow from our faith and the richness of our learning environment. I encourage you to examine your personal goals, consult with your family and work with your school’s guidance counsellors and teachers before making course selections as they can provide you with added support to ensure that your secondary school experience is a successful one. We are confident that you will enjoy your secondary school experience as you prepare yourself for your future.