4. Kwok Growth and Decline of Chinese Mining on the Turon Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’S Guide

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Important: This Operator’s Guide is for three Notices separated by Part A, Part B and Part C. Please read sections carefully as separate conditions may apply. For enquiries about roads and restrictions listed in this document please contact Transport for NSW Road Access unit: [email protected] 27 October 2020 New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Contents Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 NSW Travel Zones .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Part A – NSW Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicles Notice ................................................................................................ 9 About the Notice ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 1: Travel Conditions ................................................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Pilot and Escort Requirements .......................................................................................................................... -

2013 ANZSI Conference: “Intrepid Indexing: Indexing Without

Intrepid indexing: indexing without boundaries 13–15 March 2013 Wellington, New Zealand Table of Contents Papers • Keynote: Intrepid indexing: from the sea to the stars, Jan Wright • Publishers, Editors and Indexers: a panel discussion, Fergus Barrowman, Mei Yen Chua and Simon Minto • Māori names and terms in indexes, texts and databases, Robin Briggs, Ross Calman, Carol Dawber • EPUB3 Indexes Charter and the future of indexing, Glenda Browne • People and place : the future of database indexing for Indigenous collections in Australia, Judith Cannon and Jenny Wood • Indexing military history, Peter Cooke • Ethics in Indexing, Heather Ebbs • Running an Indexing Business, Heather Ebbs, Pilar Wyman, Mary Coe and Tordis Flath • Archives and indexing history in the Pacific Islands, Uili Fecteau and Margaret Pointer • Typesetting Dilemmas, Tordis Flath and Mary Russell • Can an index be a work of art? Lynn Jenner and Tordis Flath • Advanced SKY Index, Jon Jermey • East Asian names: understanding and indexing Chinese, Japanese and Korean (CJK) names, Lai Lam and Cornelia (Nelly) Bess • Intermediate CINDEX - Patterns for the Plucky, Frances Lennie • Demystifying indexing: keeping the editor sane! Max McMaster (presented by Mary Russell) • Numbers in Indexing, Max McMaster (presented by Mary Russell) • Japan's indexing practice, Takashi Matsuura • Understanding Asian Names, Fiona Price • Indexing Tips and Traps; Practical approaches to improving indexes and achieving ANZSI Accreditation, Sherrey Quinn o Indexing Tip and Traps — slides o Practical -

Portfolio Management Plan Macquarie River Valley

Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan Macquarie River Valley 2018–19 Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Front cover image credit: Sinclairs Lagoon, Photo by Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. Back cover image credit: Lower Macquarie, Photo by Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. Acknowledgement of the traditional owners of the Murray-Darling Basin The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office respectfully acknowledges the traditional owners, their Elders past and present, their Nations of the Murray-Darling Basin, and their cultural, social, environmental, spiritual and economic connection to their lands and waters. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2018. Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan: Macquarie River Valley 2018–19 is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This report should be attributed as ‘Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan: Macquarie River Valley 2018–19, Commonwealth of Australia, 2018’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright’ noting the third party. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Energy. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

How Do Lachlan Valley Cotton Soils Compare to Cotton Soils in Northern NSW?

How do Lachlan Valley cotton soils compare to cotton soils in northern NSW? By Alex Onus, Stephen Cattle, and Inakwu Odeh, The University of Sydney, and the Australian Cotton Cooperative Research Centre Recently, a soil survey project was carried out in the lower Lachlan Valley around the township of Hillston with the aim of identifying current and potential soil limitations to cotton production in this region. Within the lower Lachlan cotton-growing area, three main soil classes were identified, each with distinct features which influence cotton production. Soil features were also compared with other cotton-growing valleys in northern NSW, and it was found that subsoil sodicity and structural instability pose the greatest potential threat to cotton production in the lower Lachlan. Other potential soil limitations which will require consideration in regard to cotton production in the lower Lachlan include subsoil alkalinity and deficiencies in organic carbon and subsoil phosphorus. Cotton production in eastern Australia occurs on the numerous river plains of the Murray-Darling river system. In recent years, the cotton industry has expanded from the more traditional cotton-growing regions of northern NSW and southern Qld into new river plain areas such as the lower Lachlan Valley in southern NSW. Some distinct differences exist, however, between southern and northern growing regions of NSW, particularly with regard to climatic conditions. It is important for the success of cotton production in southern NSW, that management techniques that have been developed in established cotton-growing regions of northern NSW are modified and adapted to southern NSW cotton-growing regions. This article specifically examines features of the soil resource in the lower Lachlan River Valley, particularly around the township of Hillston, with a view to identifying current and potential soil limitations to cotton production in this region. -

Appendix 1 - Fish Species Occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins 271

Appendix 1 - Fish species occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins 271 Appendix 1 - Fish species occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins Table 1 Fish species recorded in the Richmond River drainage basin (DWR catchment code 203) in the NSW Rivers Survey ("1996 Survey") and a previous study (Llewellyn 1983)("1983 Survey"). Site code Site name Stream Nearest town NCRL46 Casino Richmond River Casino NCRL50 Dunoon Rocky Creek Lismore NCRL48 Tintenbar Emigrant Creek Tintenbar NCUL60 Lismore Leycester Creek Lismore Species 1996 Survey* 1983 Survey Acanthopagrus australis 10 Ambassis agassizii 10 Ambassis nigripinnis 11 Anguilla australis 01 Anguilla reinhardtii 10 Arius graeffei 10 Arrhamphus sclerolepis 10 Carcharhinus leucas 10 Gambusia holbrooki 11 Gnathanodon speciosus 10 Gobiomorphus australis 11 Gobiomorphus coxii 01 Herklotsichthys castelnaui 10 Hypseleotris compressa 11 Hypseleotris galii 11 Hypseleotris spp 1 0 Liza argentea 10 Macquaria colonorum 10 Macquaria novemaculeata 10 Melanotaenia duboulayi 11 Mugil cephalus 11 Myxus petardi 11 Notesthes robusta 11 Philypnodon grandiceps 10 Philypnodon sp1 1 0 Platycephalus fuscus 10 Potamalosa richmondia 10 Pseudomugil signifer 11 Retropinna semoni 11 Tandanus tandanus 11 Total 28 14 *1 - Species recorded, 0 - Species not recorded (Details of fish records at individual sites and times are given in Harris et al. (1996). CRC For Freshwater Ecology RACAC NSW Fisheries 272 NSW Rivers Survey Table 2 Fish species recorded in the Clarence River drainage basin (DWR catchment code 204) in the NSW Rivers -

Gemstones and Geosciences in Space and Time Digital Maps to the “Chessboard Classification Scheme of Mineral Deposits”

Earth-Science Reviews 127 (2013) 262–299 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Gemstones and geosciences in space and time Digital maps to the “Chessboard classification scheme of mineral deposits” Harald G. Dill a,b,⁎,BertholdWeberc,1 a Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, P.O. Box 510163, D-30631 Hannover, Germany b Institute of Geosciences — Gem-Materials Research and Economic Geology, Johannes-Gutenberg-University, Becherweg 21, D-55099 Mainz, Germany c Bürgermeister-Knorr Str. 8, D-92637 Weiden i.d.OPf., Germany article info abstract Article history: The gemstones, covering the spectrum from jeweler's to showcase quality, have been presented in a tripartite Received 27 April 2012 subdivision, by country, geology and geomorphology realized in 99 digital maps with more than 2600 mineral- Accepted 16 July 2013 ized sites. The various maps were designed based on the “Chessboard classification scheme of mineral deposits” Available online 25 July 2013 proposed by Dill (2010a, 2010b) to reveal the interrelations between gemstone deposits and mineral deposits of other commodities and direct our thoughts to potential new target areas for exploration. A number of 33 categories Keywords: were used for these digital maps: chromium, nickel, titanium, iron, manganese, copper, tin–tungsten, beryllium, Gemstones fl Country lithium, zinc, calcium, boron, uorine, strontium, phosphorus, zirconium, silica, feldspar, feldspathoids, zeolite, Geology amphibole (tiger's eye), olivine, pyroxenoid, garnet, epidote, sillimanite–andalusite, corundum–spinel−diaspore, Geomorphology diamond, vermiculite–pagodite, prehnite, sepiolite, jet, and amber. Besides the political base map (gems Digital maps by country) the mineral deposit is drawn on a geological map, illustrating the main lithologies, stratigraphic Chessboard classification scheme units and tectonic structure to unravel the evolution of primary gemstone deposits in time and space. -

Frederick Dalton (1815–80): Uncovering a Life in Gold

Frederick Dalton (1815–80): Uncovering a life in gold BRENDAN DALTON My father died in 1997 at 70 years of age. He had grown up without a father. In 1927, a few months after my father’s birth, my grandfather Herbert Arthur Dalton died. The male influences in my father’s early life were his maternal uncles— the Leonards—and the Christian Brothers. He grew up with a very strong sense of his own history as fundamentally Irish Australian, Catholic, working class and, in spite of his name, as a Leonard. Dalton being a fairly common Irish name, he assumed that his father’s family had the same background. For my father there was pride in this ancestry; pride based in the love he felt for the unpretentious, deeply religious, funny, heroic (World War I being a very big part of his family story) and loving people, the aunts and uncles that he had known. While he may have been comfortable with this story, my father felt its contradictions, at times deeply. We have one photograph of my Dalton grandfather, bending to reward a happy and well-trained dog: an Airedale. The man is already 50, tall, in a dark suit and moustachioed in the style of Henry Lawson, almost stereotypically ‘Australian’ from the period before World War I. His look could not be more different to the big-eared, long faces and shorter statures of the Leonard males. I have known this photograph all my life and I also know that my father rarely looked at it. Perhaps the mystery of his father was too great and the need to know more, too profoundly insatiable. -

The Gold Colonies of Australia Than Has Ever Before Been Brought Within So Moderate a Com Pass and Price

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

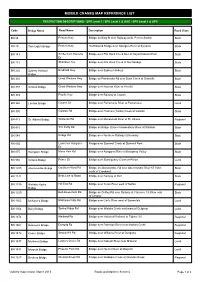

Mobile Crane Network

MOBILE CRANES MAP REFERENCE LIST RESTRICTION DESCRIPTIONS - SPV Level 1 / SPV Level 1 & UAC / SPV Level 1 & UPC Code Bridge Name Road Name Description Road Class BN 24 Princes Hwy Bridge on King St over Railway at St. Peter's Station State BN 29 Tom Ugly's Bridge Princes Hwy Northbound Bridge over George's River at Sylvania State BN 143 Sir Bertram Stevens Bridge over Flat Rock Creek No2 at Royal National Park State Dr BN 172 Stahallen Ave Bridge over Flat Rock Creek at Northbridge State BN 226 Sydney Harbour Bradfield Hwy Bridge over Sydney Harbour State Bridge BN 316 Great Western Hwy Bridge on Parramatta Rd over Duck Creek at Granville State BN 333 Victoria Bridge Great Western Hwy Bridge over Nepean River at Penrith State BN 339 Pacific Hwy Bridge over Railway at Cowan State BN 360 Lennox Bridge Church St Bridge over Parramatta River at Parramatta Local BN 390 Galston Rd Bridge over Pearces (Tunks) Creek at Galston State BN 413 St. Albans Bridge Wollombi Rd Bridge over Macdonald River at St. Albans Regional BN 415 The Putty Rd Bridge on Bridge St over Hawkesbury River at Windsor State BN 548 Bridge Rd Bridge over Northern Railway at Hornsby State BN 856 Lawrence Hargrave Bridge over Stanwell Creek at Stanwell Park State Dr BN 875 Hampden Bridge Moss Vale Rd Bridge over Kangaroo River at Kangaroo Valley State BN 965 Victoria Bridge Prince St Bridge over Stonequarry Creek at Picton Local BN 1015 Abercrombie Bridge Goulburn-Ilford Rd Bridge on Abercrombie Rd over Abercrombie River 67.16km State north of Crookwell BN 1141 Bells Line of -

Strategic Representations of Chinese Cultural Elements in Maxine Hong Kingston's and Amy Tan's Works

School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts When Tiger Mothers Meet Sugar Sisters: Strategic Representations of Chinese Cultural Elements in Maxine Hong Kingston's and Amy Tan's Works Sheng Huang This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University December 2017 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: …………………………………………. Date: ………………………... i Abstract This thesis examines how two successful Chinese American writers, Maxine Hong Kingston and Amy Tan, use Chinese cultural elements as a strategy to challenge stereotypes of Chinese Americans in the United States. Chinese cultural elements can include institutions, language, religion, arts and literature, martial arts, cuisine, stock characters, and so on, and are seen to reflect the national identity and spirit of China. The thesis begins with a brief critical review of the Chinese elements used in Kingston’s and Tan’s works, followed by an analysis of how they created their distinctive own genre informed by Chinese literary traditions. The central chapters of the thesis elaborate on how three Chinese elements used in their works go on to interact with American mainstream culture: the character of the woman warrior, Fa Mu Lan, who became the inspiration for the popular Disney movie; the archetype of the Tiger Mother, since taken up in Amy Chua’s successful book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother; and Chinese style sisterhood which, I argue, is very different from the ‘sugar sisterhood’ sometimes attributed to Tan’s work. -

23 Aug 2018 (Jil. 62, No. 17, TMA No

M A L A Y S I A Warta Kerajaan S E R I P A D U K A B A G I N D A DITERBITKAN DENGAN KUASA HIS MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Jil. 62 TAMBAHAN No. 17 23hb Ogos 2018 TMA No. 34 No. TMA 104. AKTA CAP DAGANGAN 1976 (Akta 175) PENGIKLANAN PERMOHONAN UNTUK MENDAFTARKAN CAP DAGANGAN Menurut seksyen 27 Akta Cap Dagangan 1976, permohonan-permohonan untuk mendaftarkan cap dagangan yang berikut telah disetuju terima dan adalah dengan ini diiklankan. Jika sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan disetuju terima dengan tertakluk kepada apa-apa syarat, pindaan, ubahsuaian atau batasan, syarat, pindaan, ubahsuaian atau batasan tersebut hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan. Jika sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan di bawah perenggan 10(1)(e) Akta diiklankan sebelum penyetujuterimaan menurut subseksyen 27(2) Akta itu, perkataan-perkataan “Permohonan di bawah perenggan 10(1)(e) yang diiklankan sebelum penyetujuterimaan menurut subseksyen 27(2)” hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan itu. Jika keizinan bertulis kepada pendaftaran yang dicadangkan daripada tuanpunya berdaftar cap dagangan yang lain atau daripada pemohon yang lain telah diserahkan, perkataan-perkataan “Dengan Keizinan” hendaklah dinyatakan dalam iklan, menurut peraturan 33(3). WARTA KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN WARTA KERAJAAN PERSEKUTUAN 12742 [23hb Ogos 2018 23hb Ogos 2018] PB Notis bangkangan terhadap sesuatu permohonan untuk mendaftarkan suatu cap dagangan boleh diserahkan, melainkan jika dilanjutkan atas budi bicara Pendaftar, dalam tempoh dua bulan dari tarikh Warta ini, menggunakan Borang CD 7 berserta fi yang ditetapkan. TRADE MARKS ACT 1976 (Act 175) ADVERTISEMENT OF APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF TRADE MARKS Pursuant to section 27 of the Trade Marks Act 1976, the following applications for registration of trade marks have been accepted and are hereby advertised. -

Turon National Park 1

Statement of Management Intent Turon National Park 1. Introduction This statement outlines the main values, issues, management directions and priorities of the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) for managing Turon National Park. This statement, together with relevant NPWS policies, will guide the management of the park until a plan of management has been prepared in accordance with the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NPW Act). The NPWS Managing Parks Prior to Plan of Management Policy states that parks and reserves without a plan of management are to be managed in a manner consistent with the intent of the NPW Act and the ‘precautionary principle’ (see Principle 15). 2. Management principles National parks are reserved under the NPW Act to protect and conserve areas containing outstanding or representative ecosystems, natural or cultural features or landscapes or phenomena that provide opportunities for public appreciation, inspiration and sustainable visitor or tourist use and enjoyment. Under the NPW Act (section 30E), national parks are managed to: • conserve biodiversity, maintain ecosystem functions, and protect geological and geomorphological features and natural phenomena and maintain natural landscapes • conserve places, objects, features and landscapes of cultural value • protect the ecological integrity of one or more ecosystems for present and future generations • promote public appreciation and understanding of the park’s natural and cultural values • provide for sustainable visitor or tourist use and enjoyment that is compatible with conservation of natural and cultural values • provide for sustainable use (including adaptive reuse) of any buildings or structures or modified natural areas having regard to conservation of natural and cultural values • provide for appropriate research and monitoring.