Frederick Dalton (1815–80): Uncovering a Life in Gold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’S Guide

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Important: This Operator’s Guide is for three Notices separated by Part A, Part B and Part C. Please read sections carefully as separate conditions may apply. For enquiries about roads and restrictions listed in this document please contact Transport for NSW Road Access unit: [email protected] 27 October 2020 New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Contents Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 NSW Travel Zones .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Part A – NSW Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicles Notice ................................................................................................ 9 About the Notice ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 1: Travel Conditions ................................................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Pilot and Escort Requirements .......................................................................................................................... -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

Portfolio Management Plan Macquarie River Valley

Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan Macquarie River Valley 2018–19 Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Front cover image credit: Sinclairs Lagoon, Photo by Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. Back cover image credit: Lower Macquarie, Photo by Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. Acknowledgement of the traditional owners of the Murray-Darling Basin The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office respectfully acknowledges the traditional owners, their Elders past and present, their Nations of the Murray-Darling Basin, and their cultural, social, environmental, spiritual and economic connection to their lands and waters. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2018. Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan: Macquarie River Valley 2018–19 is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This report should be attributed as ‘Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan: Macquarie River Valley 2018–19, Commonwealth of Australia, 2018’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright’ noting the third party. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Energy. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

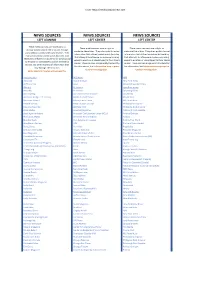

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon -

Sydney Is Singularly Fortunate in That, Unlike Other Australian Cities, Its Newspaper History Has Been Well Documented

Two hundred years of Sydney newspapers: A SHORT HISTORY By Victor Isaacs and Rod Kirkpatrick 1 This booklet, Two Hundreds Years of Sydney Newspapers: A Short History, has been produced to mark the bicentenary of publication of the first Australian newspaper, the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, on 5 March 1803 and to provide a souvenir for those attending the Australian Newspaper Press Bicentenary Symposium at the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, on 1 March 2003. The Australian Newspaper History Group convened the symposium and records it gratitude to the following sponsors: • John Fairfax Holdings Ltd, publisher of Australia’s oldest newspaper, the Sydney Morning Herald • Paper World Pty Ltd, of Melbourne, suppliers of original newspapers from the past • RMIT University’s School of Applied Communication, Melbourne • The Printing Industries Association of Australia • The Graphic Arts Merchants Association of Australia • Rural Press Ltd, the major publisher of regional newspapers throughout Australia • The State Library of New South Wales Printed in February 2003 by Rural Press Ltd, North Richmond, New South Wales, with the assistance of the Printing Industries Association of Australia. 2 Introduction Sydney is singularly fortunate in that, unlike other Australian cities, its newspaper history has been well documented. Hence, most of this short history of Sydney’s newspapers is derived from secondary sources, not from original research. Through the comprehensive listing of relevant books at the end of this booklet, grateful acknowledgement is made to the writers, and especially to Robin Walker, Gavin Souter and Bridget Griffen-Foley whose work has been used extensively. -

James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 179O—I821

I JAMES PERRY AND THE MORNING CHRONICLE- 179O—I821 By l yon Asquith Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London 1973 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Preface 5 1. 1790-1794 6 2. 1795-1 805 75 3. 1806-1812 (i) ThB Ministry of the Talents 184 (ii) Reform, Radicalism and the War 1808-12 210 (iii) The Whigs arid the Morning Chronicle 269 4. Perry's Advertising Policy 314 Appendix A: Costs of Production 363 Appendix B: Advertising Profits 365 Appendix C: Government Advertisements 367 5. 1813-1821 368 Conclusion 459 Bibliography 467 3 A BSTRACT This thesis is a study of the career of James Perry, editor and proprietor of the Morning Chronicle, from 1790-1821. Based on an examination of the correspondence of whig and radical polit- icians, and of the files of the morning Chronicle, it illustrates the impact which Perry made on the world of politics and journalism. The main questions discussed are how Perry responded, as a Foxite journalist, to the chief political issues of the day; the extent to which the whigs attempted to influence his editorial policy and the degree to which he reconciled his independence with obedience to their wishes4 the difficulties he encountered as the spokesman of an often divided party; his considerable involvement, which was remarkable for a journalist, in party activity and in the social life of whig politicians; and his success as a newspaper proprietor concerned not only with political propaganda, but with conducting a paper which was distinguished for the quality of its miscellaneous features and for its profitability as a business enterprise. -

How Do Lachlan Valley Cotton Soils Compare to Cotton Soils in Northern NSW?

How do Lachlan Valley cotton soils compare to cotton soils in northern NSW? By Alex Onus, Stephen Cattle, and Inakwu Odeh, The University of Sydney, and the Australian Cotton Cooperative Research Centre Recently, a soil survey project was carried out in the lower Lachlan Valley around the township of Hillston with the aim of identifying current and potential soil limitations to cotton production in this region. Within the lower Lachlan cotton-growing area, three main soil classes were identified, each with distinct features which influence cotton production. Soil features were also compared with other cotton-growing valleys in northern NSW, and it was found that subsoil sodicity and structural instability pose the greatest potential threat to cotton production in the lower Lachlan. Other potential soil limitations which will require consideration in regard to cotton production in the lower Lachlan include subsoil alkalinity and deficiencies in organic carbon and subsoil phosphorus. Cotton production in eastern Australia occurs on the numerous river plains of the Murray-Darling river system. In recent years, the cotton industry has expanded from the more traditional cotton-growing regions of northern NSW and southern Qld into new river plain areas such as the lower Lachlan Valley in southern NSW. Some distinct differences exist, however, between southern and northern growing regions of NSW, particularly with regard to climatic conditions. It is important for the success of cotton production in southern NSW, that management techniques that have been developed in established cotton-growing regions of northern NSW are modified and adapted to southern NSW cotton-growing regions. This article specifically examines features of the soil resource in the lower Lachlan River Valley, particularly around the township of Hillston, with a view to identifying current and potential soil limitations to cotton production in this region. -

Appendix 1 - Fish Species Occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins 271

Appendix 1 - Fish species occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins 271 Appendix 1 - Fish species occurrence in NSW River Drainage Basins Table 1 Fish species recorded in the Richmond River drainage basin (DWR catchment code 203) in the NSW Rivers Survey ("1996 Survey") and a previous study (Llewellyn 1983)("1983 Survey"). Site code Site name Stream Nearest town NCRL46 Casino Richmond River Casino NCRL50 Dunoon Rocky Creek Lismore NCRL48 Tintenbar Emigrant Creek Tintenbar NCUL60 Lismore Leycester Creek Lismore Species 1996 Survey* 1983 Survey Acanthopagrus australis 10 Ambassis agassizii 10 Ambassis nigripinnis 11 Anguilla australis 01 Anguilla reinhardtii 10 Arius graeffei 10 Arrhamphus sclerolepis 10 Carcharhinus leucas 10 Gambusia holbrooki 11 Gnathanodon speciosus 10 Gobiomorphus australis 11 Gobiomorphus coxii 01 Herklotsichthys castelnaui 10 Hypseleotris compressa 11 Hypseleotris galii 11 Hypseleotris spp 1 0 Liza argentea 10 Macquaria colonorum 10 Macquaria novemaculeata 10 Melanotaenia duboulayi 11 Mugil cephalus 11 Myxus petardi 11 Notesthes robusta 11 Philypnodon grandiceps 10 Philypnodon sp1 1 0 Platycephalus fuscus 10 Potamalosa richmondia 10 Pseudomugil signifer 11 Retropinna semoni 11 Tandanus tandanus 11 Total 28 14 *1 - Species recorded, 0 - Species not recorded (Details of fish records at individual sites and times are given in Harris et al. (1996). CRC For Freshwater Ecology RACAC NSW Fisheries 272 NSW Rivers Survey Table 2 Fish species recorded in the Clarence River drainage basin (DWR catchment code 204) in the NSW Rivers -

Gemstones and Geosciences in Space and Time Digital Maps to the “Chessboard Classification Scheme of Mineral Deposits”

Earth-Science Reviews 127 (2013) 262–299 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Gemstones and geosciences in space and time Digital maps to the “Chessboard classification scheme of mineral deposits” Harald G. Dill a,b,⁎,BertholdWeberc,1 a Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, P.O. Box 510163, D-30631 Hannover, Germany b Institute of Geosciences — Gem-Materials Research and Economic Geology, Johannes-Gutenberg-University, Becherweg 21, D-55099 Mainz, Germany c Bürgermeister-Knorr Str. 8, D-92637 Weiden i.d.OPf., Germany article info abstract Article history: The gemstones, covering the spectrum from jeweler's to showcase quality, have been presented in a tripartite Received 27 April 2012 subdivision, by country, geology and geomorphology realized in 99 digital maps with more than 2600 mineral- Accepted 16 July 2013 ized sites. The various maps were designed based on the “Chessboard classification scheme of mineral deposits” Available online 25 July 2013 proposed by Dill (2010a, 2010b) to reveal the interrelations between gemstone deposits and mineral deposits of other commodities and direct our thoughts to potential new target areas for exploration. A number of 33 categories Keywords: were used for these digital maps: chromium, nickel, titanium, iron, manganese, copper, tin–tungsten, beryllium, Gemstones fl Country lithium, zinc, calcium, boron, uorine, strontium, phosphorus, zirconium, silica, feldspar, feldspathoids, zeolite, Geology amphibole (tiger's eye), olivine, pyroxenoid, garnet, epidote, sillimanite–andalusite, corundum–spinel−diaspore, Geomorphology diamond, vermiculite–pagodite, prehnite, sepiolite, jet, and amber. Besides the political base map (gems Digital maps by country) the mineral deposit is drawn on a geological map, illustrating the main lithologies, stratigraphic Chessboard classification scheme units and tectonic structure to unravel the evolution of primary gemstone deposits in time and space. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

An early photo of the Gippsland Standard production room. The newspaper—initially called the Gippsland Standard and Alberton, Foster, Port Albert, Tarraville, Woodside, Woranga and Yarram Representative— began at Port Albert, Victoria, on 5 March 1875. It later moved to Yarram and continued publication until 29 September 1971. It amalgamated with the Yarram News and became the Yarram Standard News. In 2009, it became the Yarram Standard. It ceased publication, during COVID-19, in March 2020. The photo shows John Rossiter (white beard), and a son, Augustus John (centre), with two employees. Some of the old type cases, make-up benches and machinery remained in the office in 1975. This image was featured in publicity material at the centenary celebration of the Victorian Country Press Association in 2010. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 112 May 2021 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, F. R. Hist. S. Q., of U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected]/ Published in memory of Victor Mark Isaacs (1949-2019), founding editor. Back copies of the Newsletter and copies of some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 15 July 2021. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000; the Newsletter has appeared five times a year since 2001. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 112.1.1 Shift in Fairfax emphasis on Nine board, and new CEO Board: Fairfax Media’s influence in the Nine Entertainment Co boardroom is close to ending with the resignation of a key director and uncertainty over the future of two other directors with ties to the historic publisher (Sydney Morning Herald, 1 March 2021). -

The Gold Colonies of Australia Than Has Ever Before Been Brought Within So Moderate a Com Pass and Price

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us.