Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from Indomalaya and Australasia, with a Redescription of P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Field Ecology 2009

Journal of Field Ecology 2009 FOREST DYNAMICS Species-independent, Scale-invariant self-similarity in the Daniel Poon 7 allometry of branches and trunks within a heterogeneous forest Disturbance and fire refugia: deviations from invariant scaling Jane Remfert 14 relations across plant communities Looking for a DBH power function in Cassandra Bog Woods Elizabeth Hood 20 Testing for self thinning in oaks and comparing results in the Melissa Brady 25 presence of Gayluccacia Biases in spatial sampling for size frequency distributions Theresa Ong 31 Neutral theory and the predictions of the species distribution of an Melissa Brady 43 edge habitat Seedling establishment over a disturbance gradient exposes a Daniel Poon 47 species dominance shift within an oak-hickory forest SPATIAL PATTERN FORMATION Examining ant mosaic in the Big Woods of the E.S. George Hyunmin Han 55 Reserve Adventures in self-organization: spatial distribution of Japanese Amanda Grimm 63 Barberry in the E.S. George Reserve Distribution of Sarracenia purpurea clusters in Hidden Lake Hyunmin Han 68 Bog of the E.S. George Reserve BOTANY A survey of host-liana relationships in a Michigan oak-hickory Jane Remfert 74 forest: specificity and overwhelmedness Vine distribution and colonization preferences in the Big Woods Alexa Unruh 81 Examining the relationship between growth and reproduction in Megan Banka 88 perennial forbs Ramets and rhizomes: trade-offs in clonal plants in relation to Elizabeth Hood 96 water availability Hybridization among Quercus veluntina and Quercus rubra is Semoya Phillips 100 evident but a pattern of organization is not COMMUNITY COMPOSITION The halo of life: patterns in ant species richness in a Michigan Leslie McGinnis 105 scrubland The effect of an environmental gradient on species abundance in Jane Skillman 111 Cassandra Bog Stands of Typha sp. -

Predicting Future Coexistence in a North American Ant Community Sharon Bewick1,2, Katharine L

Predicting future coexistence in a North American ant community Sharon Bewick1,2, Katharine L. Stuble1, Jean-Phillipe Lessard3,4, Robert R. Dunn5, Frederick R. Adler6,7 & Nathan J. Sanders1,3 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 2National Institute for Mathematical and Biological Synthesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 3Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark 4Quebec Centre for Biodiversity Science, Department of Biology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 5Department of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 6Department of Mathematics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 7Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah Keywords Abstract Ant communities, climate change, differential equations, mechanistic models, species Global climate change will remodel ecological communities worldwide. How- interactions. ever, as a consequence of biotic interactions, communities may respond to cli- mate change in idiosyncratic ways. This makes predictive models that Correspondence incorporate biotic interactions necessary. We show how such models can be Sharon Bewick, Department of Biology, constructed based on empirical studies in combination with predictions or University of Maryland, College Park, MD assumptions regarding the abiotic consequences of climate change. Specifically, 20742, USA. Tel: 724-833-4459; we consider a well-studied ant community in North America. First, we use his- Fax: 301-314-9358; E-mail: [email protected] torical data to parameterize a basic model for species coexistence. Using this model, we determine the importance of various factors, including thermal Funding Information niches, food discovery rates, and food removal rates, to historical species coexis- RRD and NJS were supported by DOE-PER tence. -

Arthropods of Public Health Significance in California

ARTHROPODS OF PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE IN CALIFORNIA California Department of Public Health Vector Control Technician Certification Training Manual Category C ARTHROPODS OF PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE IN CALIFORNIA Category C: Arthropods A Training Manual for Vector Control Technician’s Certification Examination Administered by the California Department of Health Services Edited by Richard P. Meyer, Ph.D. and Minoo B. Madon M V C A s s o c i a t i o n of C a l i f o r n i a MOSQUITO and VECTOR CONTROL ASSOCIATION of CALIFORNIA 660 J Street, Suite 480, Sacramento, CA 95814 Date of Publication - 2002 This is a publication of the MOSQUITO and VECTOR CONTROL ASSOCIATION of CALIFORNIA For other MVCAC publications or further informaiton, contact: MVCAC 660 J Street, Suite 480 Sacramento, CA 95814 Telephone: (916) 440-0826 Fax: (916) 442-4182 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.mvcac.org Copyright © MVCAC 2002. All rights reserved. ii Arthropods of Public Health Significance CONTENTS PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................ v DIRECTORY OF CONTRIBUTORS.............................................................................................. vii 1 EPIDEMIOLOGY OF VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES ..................................... Bruce F. Eldridge 1 2 FUNDAMENTALS OF ENTOMOLOGY.......................................................... Richard P. Meyer 11 3 COCKROACHES ........................................................................................... -

I. Petiole Node II. Tip of Abdomen IV. Length of Antennae Guide to Vineyard Ant Identification III. Shape of Thorax

Guide to Vineyard Ant Identification head abdomen Monica L. Cooper, Viticulture Farm Advisor, Napa County Lucia G. Varela, North Coast IPM Advisor thorax I. Petiole node One Node Two nodes Go to II Subfamily Myrmicinae Go to V II. Tip of abdomen Circle of small hairs present Circle of small hairs absent Subfamily Formicinae Subfamily Dolichoderinae Go to III Argentine Ant (Linepithema humile) III. Shape of thorax Thorax uneven Thorax smooth and rounded Go to IV Subfamily Formicinae Carpenter ant (Camponotus spp.) IV. Length of antennae Antennae not much longer than length of head Antennae much longer than length of head Subfamily Formicinae Subfamily Formicinae Field or Gray Ant (Formica spp.) False honey ant (Prenolepis imparis) head abdomen Petiole with two nodes Subfamily Myrmicinae (V-VIII) thorax V. Dorsal side of Thorax & Antennae One pair of spines on thorax No spines on thorax 12 segmented antennae 10 segmented antennae Go to VI Solenopsis molesta and Solenopsis xyloni VI. Underside of head No brush of bristles Brush of long bristles Go to VII Harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex californicus and P. brevispinosis) VII. Head and Thorax With hairs Without hairs Go to VIII Cardiocondyla mauritanica VIII. Head and Thorax With many parallel furrows Without parallel furrows Profile of thorax rounded Profile of thorax not evenly rounded Pavement ant (Tetramorium “species E”) Pheidole californica Argentine Ant (Linepithema humile), subfamily Dolichoderinae Exotic species 3-4 mm in length Deep brown to light black Move rapidly in distinct trails Feed on honeydew Shallow nests (2 inches from soil surface) Alex Wild Does not bite or sting Carpenter Ant (Camponotus spp.), subfamily Formicinae Large ant: >6 mm in length Dark color with smooth, rounded thorax Workers most active at dusk and night One of most abundant and widespread genera worldwide Generalist scavengers and predators: feed on dead and living insects, nectar, fruit juices and Jack K. -

Pollination Biology of Ailanthus Altissima (Mill.) Swingle (Tree-Of-Heaven) in the Mid- Atlantic United States

Pollination Biology of Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle (Tree-of-Heaven) in the Mid- Atlantic United States Jessica S. Thompson Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Life Sciences In Entomology Richard D. Fell Carlyle C. Brewster P. Lloyd Hipkins R. Jay Stipes May 6, 2008 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: pollination, Ailanthus altissima, tree-of-heaven, nectar Copyright 2008 Pollination Biology of Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle (Tree-of-Heaven) in the Mid- Atlantic United States Jessica S. Thompson ABSTRACT To date little information has been collected on the pollination biology of Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle (tree-of-heaven), an invasive exotic in the U.S. This study was conducted to determine the insect pollinator fauna visiting A. altissima and to study general pollinator visitation patterns associated with the tree’s nectar profile. A list of taxa visiting trees within each of three sites was developed from collected insects. Overall, visitor assemblage was dominated by the soldier beetle Chauliognathus marginatus with large numbers of ants in the genera Formica, Prenolepis, and Camponotus. No major diurnal pattern was found for visitation of insect pollinators using instantaneous counts. The nectar composition, concentration, and amount of total sugars in the flowers of A. altissima and how these are related to tree gender and time of day were determined. Nectar was found to be sucrose-dominant with lower, but nearly equal amounts of fructose and glucose. Total amounts of sugar in male and female blossoms were not statistically different, however higher concentrations of sugar were found in males (40.7%) than in females (35.3%). -

Nylanderia (=Paratrechina) Pubens (Forel) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Formicinae)1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. EENY284 Caribbean Crazy Ant (proposed common name), Nylanderia (=Paratrechina) pubens (Forel) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Formicinae)1 John Warner and Rudolph H. Scheffrahn2 Introduction Samples of N. pubens collected in Coral Gables and Miami, Florida, date from 1953 (Trager 1984). Beginning about 2000, reports have escalated of Klotz et al. (1995) report infestations in Boca Raton, a golden-brown to reddish-brown "crazy ant" Homestead, and Miami and state that "in 1990, infesting properties in and around West Palm Beach, hundreds of these ants were found on the second Florida. Thick foraging trails with thousands of ants floor of a large Miami hospital." Deyrup et al. (2000) occur along sidewalks, around buildings, and on trees report that it "is abundant on the campus of the and shrubs. Pest control operators using liquid and/or University of Miami, where it resembles a pale N. granular broad-range insecticides appear unable to bourbonica, foraging on sidewalks and running up control this nuisance ant. and down tree trunks." L. Davis, Jr. (2003 personal communication) has seen these ants from Everglades Synonymy National Park, Fort Lauderdale, Jacksonville, and Port St. Lucie. Specimens from Sarasota (F. Santana Paratrechina pubens Forel 1893 2003, personal communication) were also confirmed. Distribution These ants seem to have large populations where they occur and are considered a pest in Colombia (Davis Nylanderia pubens (Forel) was originally 2003, personal communication). described as Paratrechina pubens Forel from St. Vincent, Lesser Antilles, and has been found on other In the West Palm Beach area, two heavily West Indian islands, including Anguilla, Guadeloupe, infested sites were observed about 3 miles west of the and Puerto Rico (Trager 1984). -

Effect of Gland Extracts on Digging and Residing Preferences of Red Imported fire Ant Workers (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

Insect Science (2013) 20, 456–466, DOI 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01553.x ORIGINAL ARTICLE Effect of gland extracts on digging and residing preferences of red imported fire ant workers (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Jian Chen and Guangmei Zhang USDA-ARS, National Biological Control Laboratory, Biological Control of Pests Research Unit, Stoneville, MS 38776, USA Abstract There is evidence that ant-derived chemical stimuli are involved in regulat- ing the digging behavior in Solenopsis invicta Buren. However, the source gland(s) and chemistry of such stimuli have never been revealed. In this study, extracts of mandibular, Dufour’s, postpharyngeal, and poison glands were evaluated for their effect on ant digging and residing preferences of S. invicta workers from three colonies. In the intracolonial bioassays, workers showed significant digging preferences to mandibular gland extracts in 2 of 3 colonies and significant residing preferences in 1 of 3 colonies; significant digging preferences to Dufour’sgland extracts in 1 of 3 colonies and significant residing preferences in 2 of 3 colonies. No digging and residing preferences were found for postpharyngeal and poison gland extracts. In intercolonial bioassays, significant digging and residing prefer- ences were found for mandibular gland extracts in 3 of 6 colony combinations. Significant digging preferences to Dufour’s gland extracts were found in 4 of 6 colony combinations and significant residing preferences in all 6 colony combinations. For postpharyngeal gland extracts, significant digging preferences were found only in 1 of 6 colonial combinations and no significant residing preferences were found. For poison gland extracts, no signif- icant digging preferences were found; significant residing preferences were found in 1 of 6 colony combinations. -

Increased Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Incidence and Richness Are Associated with Alien Plant Cover in a Small Mid-Atlantic Riparian Forest

Myrmecological News 22 109-117 Online Earlier, for print 2016 Increased ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) incidence and richness are associated with alien plant cover in a small mid-Atlantic riparian forest Daniel KJAR & Zachory PARK Abstract Alien plants have invaded forest habitats throughout the eastern United States (US) and may be altering native ant communities through changes in disturbance regimes, microclimate, and native plant communities. To determine if ant communities differ among sites with varying alien plant cover, we analyzed pitfall-traps and soil-core samples from a mid-Atlantic riparian forest located within a US National Park. Only one alien ant species, Vollenhovia emeryi WHEELER , 1906 was found in this study. Total ant incidence and, to a lesser extent, richness were positively associated with the amount of alien plant cover. Species richness estimators also predicted more ant species within sites of greater alien plant cover. Increased ant incidence and ant richness appear to be the result of greater numbers of foraging ants in areas with greater alien plant cover rather than changes in the ant species composition. We suggest alien plant presence or other factors associated with alien plant cover have led to greater ant incidence and richness in these sites. Key words: Alien invasive plants, ant community, riparian forest, Lonicera japonica. Myrmecol. News 22: 109-117 (online xxx 2014) ISSN 1994-4136 (print), ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Received 7 April 2015; revision received 28 July 2015; accepted 3 August 2015 Subject Editor: Nicholas J. Gotelli Daniel Kjar (contact author) & Zachory Park , Elmira College , 1 Park Place , Elmira, NY 14905 , USA. -

Prenolepis Fisheri , an Intriguing New Ant Species, with a Re-Description

J. Entomol. Res. Soc., 14(1): 119-126, 2012 ISSN:1302-0250 Prenolepis fisheri, an Intriguing New Ant Species, with a Re-description of Prenolepis naoroji (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from India Himender BHARTI* Aijaz Ahmad WACHKOO Department of Zoology and Environmental Sciences, Punjabi University, Patiala, 147002, INDIA. *Corresponding author. e-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT The taxonomy of Indian Prenolepis is discussed here for the first time in detail. Prenolepis fisheri sp. n., an intriguing species described as new, is the second species of the genus known from India, with only Prenolepis naoroji Forel, 1902 reported earlier. P. fisheri sp. n. resembles the Antillean Prenolepis albimaculata Santschi, 1930; Prenolepis gibberosa Roger, 1863 and Prenolepis karstica Fontenla, 2000, sharing with them the presence of ocelli in the worker caste. All castes of Prenolepis naoroji are addressed and a key is provided to separate the Indian species. Key words: taxonomy, new species, ants, Formicinae, key, Prenolepis fisheri sp. n., Shivalik. INTRODUCTION Prenolepis Mayr is a small genus with 20 described species and six subspecies distributed widely all over the globe, but the genus reaches its highest species diversity levels in southeastern Asia and southern China (Bolton, 2011). Prenolepis awaits a global taxonomic revision, however, important taxonomic contributions in terms of species/subspecies additions to this genus include: Say (1836), Mayr (1853), Roger (1863), Emery (1893; 1900), Forel (1894; 1902; 1911; 1916), Santschi (1920; 1930), Crawley (1923), Wheeler (1930), Xu (1995), Zhou and Zheng (1998), Fontenla (2000), Zhou (2001) and Wang and Wu (2007). More recently, LaPolla et al. (2010) carried out a significant work on phylogeny and taxonomy of the Prenolepis genus group. -

The Invasive Argentine Ant Linepithema Humile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Northern California Reserves: from Foraging Behavior to Local Spread

Myrmecological News 19 103-110 Online Earlier, for print 2014 The invasive Argentine ant Linepithema humile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Northern California reserves: from foraging behavior to local spread Deborah M. GORDON & Nicole E. HELLER Abstract We review the results from a 20-year study of the spread of the invasive Argentine ant, Linepithema humile (MAYR, 1868), in a reserve in Northern California. Ecological studies show that Argentine ants disrupt native ant communities. The best predictor of Argentine ant distribution is proximity to human disturbance, because buildings and irrigation provide water in the dry season and warm, dry refuges during the rainy season. Our studies of the effects of habitat and climatic factors suggest that human disturbance promotes spread, while lack of rainfall and interactions with native species, espe- cially the native winter ant, Prenolepis imparis (SAY, 1836), slows spread in areas further from human disturbance. Genetic and behavioral studies indicate that seasonally polydomous colonies span 300 - 600 m2 in the summer when they are most dispersed, and contract to one or a few large nests in the winter. There is no evidence of mixing between nests of different colonies. Studies of foraging behavior show that searching behavior adjusts to local density, that arriving first at a food resource provides an advantage over native species, and that recruitment to food occurs from nearby existing trails rather than from more distant nests. We continue to monitor the spread and impact of the Argentine ant at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve in collaboration with citizen scientists. We are investigating how Argentine ants modify and expand their trail networks, the interactions that allow the winter ant to displace Argentine ants, and the role of human disturbance on the impact of Argentine and other invasive ants in native communities. -

Of Santa Cruz Island, California

Bull. Southern California Acad. Sei. 99(1), 2000, pp. 25-31 © Southern California Academy of Sciences, 2000 Ants (Hymenoptera: Formiddae) of Santa Cruz Island, California James K. Wetterer', Philip S. Ward^, Andrea L. Weiterer', John T. Longino^, James C. Träger^ and Scott E. Miller' ^Center for Environmental Research and Conservation, 1200 Amsterdam Ave., Columbia University, New York, New York 10027 ^Department of Entomology, University of California, Davis, California 95616 ^The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington 98505 '^Shaw Arboretum, P.O. Box 38, Gray Summit, Missouri 63039 ^International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, Box 30772, Nairobi, Kenya and National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 Abstract.•^We conducted ant surveys on Santa Cruz Island, the largest of the CaUfomia Channel Islands, in 1975/6, 1984, 1993, and 1998. Our surveys yielded a combined total of 34 different ant species: Brachymyrmex cf. depilis, Campon- otus anthrax, C. clarithorax, C. hyatti, C. semitestaceus, C. vicinus, C. sp. near vicinus, C yogi, Cardiocondyla ectopia, Crematogaster califomica, C héspera, C. marioni, C. mormonum, Dorymyrmex bicolor, D. insanus (s.l.), Formica la- sioides, F. moki, Hypoponera opacior, Leptothorax andrei, L. nevadensis, Line- pithema humile, Messor chamberlini, Monomorium ergatogyna, Pheidole califor- nica, P. hyatti, Pogonomyrmex subdentatus, Polyergus sp., Prenolepis imparis, Pseudomyrmex apache, Solenopsis molesta (s.l.), Stenamma diecki, S. snellingi, S. cf. diecki, and Tapinoma sessile. The ant species form a substantial subset of the mainland California ant fauna. "We found only two ant species that are not native to North America, C ectopia and L. humile. Linepithema humile, the Ar- gentine ant, is a destructive tramp ant that poses a serious threat to native ants. -

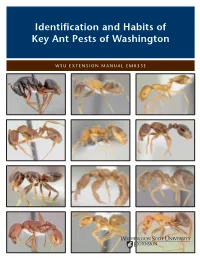

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington WSU EXTENSION MANUAL EM033E Cover images are from www.antweb.org, as photographed by April Nobile. Top row (left to right): Carpenter ant, Camponotus modoc; Velvety tree ant, Liometopum occidentale; Pharaoh ant, Monomorium pharaonis. Second row (left to right): Aphaenogaster spp.; Thief ant, Solenopsis molesta; Pavement ant, Tetramorium spp. Third row (left to right): Odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile; Ponerine ant, Hypoponera punctatissima; False honey ant, Prenolepis imparis. Bottom row (left to right): Harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex spp.; Moisture ant, Lasius pallitarsis; Thatching ant, Formica rufa. By Laurel Hansen, adjunct entomologist, Washington State University, Department of Entomology; and Art Antonelli, emeritus entomologist, WSU Extension. Originally written in 1976 by Roger Akre (deceased), WSU entomologist; and Art Antonelli. Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) are an easily anywhere from several hundred to millions of recognized group of social insects. The workers individuals. Among the largest ant colonies are are wingless, have elbowed antennae, and have a the army ants of the American tropics, with up petiole (narrow constriction) of one or two segments to several million workers, and the driver ants of between the mesosoma (middle section) and the Africa, with 30 million to 40 million workers. A gaster (last section) (Fig. 1). thatching ant (Formica) colony in Japan covering many acres was estimated to have 348 million Ants are one of the most common and abundant workers. However, most ant colonies probably fall insects. A 1990 count revealed 8,800 species of ants within the range of 300 to 50,000 individuals.