The in Racism Discussing Nagab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research the Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research The Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies Evolution of settlement typologies in rural Israel Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of "Master of Science" By: Keren Shalev November, 2016 “Human settlements are a product of their community. They are the most truthful expression of a community’s structure, its expectations, dreams and achievements. A settlement is but a symbol of the community and the essence of its creation. ”D. Bar Or” ~ III ~ תקציר למשבר הדיור בישראל השלכות מרחיקות לכת הן על המרחב העירוני והן על המרחב הכפרי אשר עובר תהליכי עיור מואצים בעשורים האחרונים. ישובים כפריים כגון קיבוצים ומושבים אשר התבססו בעבר בעיקר על חקלאות, מאבדים מאופיים הכפרי ומייחודם המקורי ומקבלים צביון עירוני יותר. נופי המרחב הכפרי הישראלי נעלמים ומפנים מקום לשכונות הרחבה פרבריות סמי- עירוניות, בעוד זהותה ודמותה הייחודית של ישראל הכפרית משתנה ללא היכר. תופעת העיור המואץ משפיעה לא רק על נופים כפריים, אלא במידה רבה גם על מרחבים עירוניים המפתחים שכונות פרבריות עם בתים צמודי קרקע על מנת להתחרות בכוח המשיכה של ישובים כפריים ולמשוך משפחות צעירות חזקות. כתוצאה מכך, סובלים המרחבים העירוניים, הסמי עירוניים והכפריים מאובדן המבנה והזהות המקוריים שלהם והשוני ביניהם הולך ומיטשטש. על אף שהנושא מעלה לא מעט סוגיות תכנוניות חשובות ונחקר רבות בעולם, מעט מאד מחקר נעשה בנושא בישראל. מחקר מקומי אשר בוחן את תהליכי העיור של המרחב הכפרי דרך ההיסטוריה והתרבות המקומית ולוקח בחשבון את התנאים המקומיים המשתנים, מאפשר התבוננות ואבחנה מדויקים יותר על ההשלכות מרחיקות הלכת. על מנת להתגבר על הבסיס המחקרי הדל בנושא, המחקר הנוכחי החל בבניית בסיס נתונים רחב של 84 ישובים כפריים (קיבוצים, מושבים וישובים קהילתיים( ומצייר תמונה כללית על תהליכי העיור של המרחב הכפרי ומאפייניה. -

Introduction Really, 'Human Dust'?

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Peck, The Lost Heritage of the Holocaust Survivors, Gesher, 106 (1982) p.107. 2. For 'Herut's' place in this matter, see H. T. Yablonka, 'The Commander of the Yizkor Order, Herut, Shoa and Survivors', in I. Troen and N. Lucas (eds.) Israel the First Decade, New York: SUNY Press, 1995. 3. Heller, On Struggling for Nationhood, p. 66. 4. Z. Mankowitz, Zionism and the Holocaust Survivors; Y. Gutman and A. Drechsler (eds.) She'erit Haplita, 1944-1948. Proceedings of the Sixth Yad Vas hem International Historical Conference, Jerusalem 1991, pp. 189-90. 5. Proudfoot, 'European Refugees', pp. 238-9, 339-41; Grossman, The Exiles, pp. 10-11. 6. Gutman, Jews in Poland, pp. 65-103. 7. Dinnerstein, America and the Survivors, pp. 39-71. 8. Slutsky, Annals of the Haganah, B, p. 1114. 9. Heller The Struggle for the Jewish State, pp. 82-5. 10. Bauer, Survivors; Tsemerion, Holocaust Survivors Press. 11. Mankowitz, op. cit., p. 190. REALLY, 'HUMAN DUST'? 1. Many of the sources posed problems concerning numerical data on immi gration, especially for the months leading up to the end of the British Mandate, January-April 1948, and the first few months of the state, May August 1948. The researchers point out that 7,574 immigrant data cards are missing from the records and believe this to be due to the 'circumstances of the times'. Records are complete from September 1948 onward, and an important population census was held in November 1948. A parallel record ing system conducted by the Jewish Agency, which continued to operate after that of the Mandatory Government, provided us with statistical data for immigration during 1948-9 and made it possible to analyse the part taken by the Holocaust survivors. -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

Reprocessing Tender

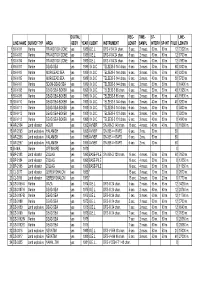

DIGITAL REC- TIME- ST- LINE- LINE-NAME SURVEY-TYP AREA -SEGY YEAR CLIENT INSTRUMENT LENGT SAMPL INTERV SP-INT FOLD LENGTH 1 80-M-01 Marine TRANSITION ZONE yes 1980 O.E.L. DFS-V-84 24 chan. 5 sec. 2 msec. 60 m. 60 m. 12 73320 m. 2 80-M-03 Marine TRANSITION ZONE yes 1980 O.E.L. DFS-V-84 24 chan. 5 sec. 2 msec. 60 m. 60 m. 12 8700 m. 3 80-M-04 Marine TRANSITION ZONE yes 1980 O.E.L. DFS-V-84 24 chan. 5 sec. 2 msec. 60 m. 60 m. 12 7980 m. 4 89-M-01 Marine DEAD SEA yes 1989 I.N.O.C TELSEIS-5 144 chan. 6 sec. 2 msec. 50 m. 50 m. 60 9300 m. 5 89-M-03 Marine MOR-DEAD SEA yes 1989 I.N.O.C TELSEIS-5 144 chan. 6 sec. 2 msec. 50 m. 50 m. 60 8300 m. 6 89-M-05 Marine MOR-DEAD SEA yes 1989 I.N.O.C TELSEIS-5 144 chan. 6 sec. 2 msec. 40 m. 80 m. 30 5720 m. 7 89-M-07 Marine SDOM-DEAD SEA yes 1989 I.N.O.C TELSEIS-5 144 chan. 6 sec. 2 msec. 50 m. 50 m. 0 16400 m. 8 90-M-08 Marine DEAD SEA-BOKEK yes 1990 I.N.O.C. TELSEIS-5 96 chan. 6 sec. 2 msec. 50 m. 50 m. 48 13950 m. 9 90-M-09 Marine DEAD SEA-BOKEK yes 1990 I.N.O.C. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Infrastructure for Growth 2020 Government of Israel TABLE of CONTENTS

Infrastructure for Growth 2020 Government of Israel TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Acting Director-General, Prime Minister’s Office, Ronen Peretz ............................................ 3 Reader’s Guide ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Summary of infrastructure projects for the years 2020-2024 Ministry of Transportation and Road Safety ................................................................................................ 8 Ministry of Energy ...................................................................................................................................... 28 Ministry of Water Resources ....................................................................................................................... 38 Ministry of Finance ..................................................................................................................................... 48 Ministry of Defense .................................................................................................................................... 50 Ministry of Health ...................................................................................................................................... 53 Ministry of Environmental Protection ......................................................................................................... 57 Ministry of Education ................................................................................................................................ -

Historical Assessment of the Transformation of Kibbutzim of Israel's

Historical Assessment of the Transformation of Kibbutzim of Israel’s Southern Arava By: Morgan E. Reisinger Project Advisors: Professor Bland Addison Professor Peter Hansen April 2019 A Major Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfilment of the requirement for degrees of Bachelor of Science This report represents work of WPI undergraduate learners submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see https://www.wpi.edu/project-based-learning Abstract Kibbutzim of Israel are utopia-driven communal settlements that spearheaded the return of Zionist Jews to Palestine in the early 1900s. Traditional kibbutzim are completely collective, meaning everything is shared equally, but make up roughly 10% of Israel’s 270 current kibbutzim. Political and financial crises compounded throughout the end of the twentieth century to initiate widespread privatization throughout Israeli kibbutzim. The purpose of this project was to assess degree to which the kibbutzim of the southern Arava transformed individually and collectively. ii Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................... ii Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. -

Name:Prof. Hanna Soker-Schwager Date: September 2020

Name: Prof. Hanna Soker-Schwager Date: September 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE AND LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Personal Details Name: Hanna Soker-Schwager Place of birth: Kibbutz Mishmar Hanegev, Israel. Regular military service: 1974-1976 Address and telephone number at work: Department of Hebrew Literature, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, POB 653, Beer Sheva 84105; Tel: 972-8-6477045 Address and telephone number at home: Kehilat Pozna 5, Tel Aviv 69989, Israel. Tel: 972-3-6473033 Education B.A.: 1977–1980 - Tel Aviv University - Hebrew Literature Department and Philosophy Department (with distinction). M.A.: 1990–1994 - Tel Aviv University - Department of Poetics and Comparative Literature (with special distinction). Name of advisor: Prof. Hanan Hever. Title of thesis: “Past Continuous by Yaakov Shabtai – Interpretation/ Problematization of Representation”. Ph.D.: 1997–2004 - Tel Aviv University - Department of Poetics and Comparative Literature. Name of Ph.D. advisor: Prof. Hannan Hever Title of Ph.D. Thesis: “Between Text and Context - Yaakov Shabtai in Israeli Culture”. Employment History 2019 – present: Associate Prof., the Department of Hebrew Literature, Ben Gurion University. 2011-present: Senior Lecturer, the Department of Hebrew Literature, Ben Gurion University. 2005-2011: Lecturer (tenure track position), the Department of Hebrew Literature, Ben Gurion University. 2005-2010: Teaching a seminar in the excellent student’s program Ofakim – Judaism as Culture –Tel Aviv University. 2005: Adjunct Professor at School of Media Studies, College of Management (Tel-Aviv). 2004-2005: Adjunct Professor at Tel Aviv University, Department of Poetics and Comparative Literature and the Department of Israeli Cultural Studies; 1999-2003: Instructor at Tel Aviv University, Department of Poetics and Comparative Literature. -

The Beduin Of the Negev

Background The Bedouin population of the Negev is 155,000, of which Israel provides its citizens with high quality public 60% lives in seven permanent townships, and the remainder services in sanitation, health and education, and in illegal homes spread over hundreds of thousands of municipal services. These services can only be provided dunams (these scattered Bedouin localities are referred to as to those living in permanent housing, and the fact that the the Bedouin “dispersal”). Bedouin are dispersed over an extensive area prevents the state from offering these public services. The rate of growth of the Negev Bedouin is the highest in the world – the Bedouin population doubles its size every Israel is currently building 13 new villages or towns 15 years. By 2020, the Bedouin population of the Negev will for the Negev Bedouin. These townships are intended to be 300,000. meet all the present and future needs of this population. The government of Israel has allocated more than [ 1 NIS1 billion for the benefit of this population. Aside from building new townships for the Bedouin in the Negev, the Israeli government plans to invest more than NIS 1 billion in a multi-phased program to improve the infrastructure of existing Bedouin towns and to develop their public facilities. Negev Bedouin claim the ownership of land that 12 times the size of Tel Aviv. In recent years, some of the Bedouin residing in the dispersed areas have started claiming ownership of land areas totaling some 600,000 dunams (60,000 hectares or 230 square miles) in the Negev – over 12 times the area of Tel Aviv! "Houses in the "dispersal ׀׀׀׀׀׀ The Israel Land Administration (ILA) is doing everything in its power to resolve the problems of the landless Bedouin in the Negev. -

Der Dornbusch, Der Nicht Verbrannte Überlebende Der Shoah in Israel

Der Dornbusch, der nicht verbrannte Überlebende der Shoah in Israel Herausgeberin: Miri Freilich Deutsche Ausgabe: Anita Haviv und Ralf Hexel Der Dornbusch, der nicht verbrannte Überlebende der Shoah in Israel Herausgeberin: Miri Freilich Deutsche Ausgabe: Anita Haviv und Ralf Hexel Übersetzung aus dem Hebräischen Rachel Grünberger-Elbaz Im Auftrag der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Israel und des Beit Berl Academic College Für die Inhalte der Beiträge tragen allein die Autorinnen und Autoren die Verantwortung. Diese stellen keine Meinungsäußerung der Herausgeber, der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung und des Beit Berl Academic College, dar. Herausgeberin: Miri Freilich Deutsche Ausgabe: Anita Haviv und Ralf Hexel Lektorat: Astrid Roth Umschlag und graphische Gestaltung: Esther Pila Satz: A.R. Print Ltd. Israel Deutsche Ausgabe 2012: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Israel P.O.Box 12235 Herzliya 46733 Israel Tel. +972 9 951 47 60 Fax +972 9 951 47 64 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Berlin Hiroshimastraße 17 D - 10785 Berlin Tel. +49 (0)30 26 935 7420 Fax +49 (0)30 26 935 9233 ISBN 978-3-86498-300-9 Hebräische Ausgabe: © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Israel 2011 Printed in Israel Inhalt Ralf Hexel Vorwort zur deutschen Ausgabe 6 Tamar Ariav Vorwort 9 Wladimir Struminski Der Optimist – Erinnerung an Noach Flug 11 Anita Haviv In memoriam Moshe Sanbar 14 Eliezer Ben-Rafael Die Shoah in der kollektiven Identität und politischen Kultur Israels 16 Hanna Yablonka Shoah-Überlebende in Israel – Schlüsselereignisse und wichtige Integrationsphasen 32 Eyal Zandberg Zwischen Privatem -

Greenwashing the Naqab: the Israeli Industry of Solar

Greenwashing the Naqab The Israeli Industry of Solar Energy February, 2017 Greenwashing the Naqab The Israeli Industry of Solar Energy February, 2017 Who Profits from the Occupation is a research center dedicated to exposing the commercial involvement of Israeli and international companies in the continued Israeli control over Palestinian and Syrian land. Who Profits operates an online database, which includes information concerning companies that are commercially complicit in the occupation. In addition, the center publishes in-depth reports and flash reports about industries, projects and specific companies. Who Profits also serves as an information center for queries regarding corporate involvement in the occupation. In this capacity, Who Profits assists individuals and civil society organizations working to end the Israeli occupation and to promote international law, corporate social responsibility, social justice and labor rights. www.whoprofits.org | [email protected] Contents Methodology 7 Greenwashing the Naqab Desert 8 Solar fields and Corporate Involvement in the Naqab Desert 10 Ketura Sun Solar Field 11 Arava Power Company 11 Ramat Hovav Solar Field 12 Energix Renewable Energies 12 First Solar 14 Zmorot Solar Field 14 EDF 15 Sde Boker and Hatzerim Solar Fields 16 Suntech Power 16 Enerpoint and Enerpoint Israel 17 Un-electri ed Bedouin communities, 19 Impoverishment, and Forced Displacement Conclusion 21 Methodology This flash report is based on both desk and field research, as well as the research conducted for the in depth report “Greenwashing the Israeli Occupation: The Solar Energy Industry and the Israeli Occupation” published by Who Profits in February 2017. The desk research includes the collection and analysis of information from various public sources, such as company records and publications, public tenders, documents of the Registrar of Companies, newspapers and other media sources, archives of photography agencies and publications by various state authorities (including Israeli government ministries). -

INVISIBLE CITIZENS Israel Government Policy Toward The

INVISIBLE CITIZENS Israel Government Policy Toward the Negev Bedouin Shlomo Swirski Yael Hasson Copyright © Adva Center 2006 All rights reserved Translation: Ruth Morris Adva Center, POB 36529 Tel Aviv 61364 Israel Tel. 03-5608871, Fax. 03-5602205 e-mail: [email protected] web site: http://www.adva.org The Center for Bedouin Studies & Development Research Unit Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva 84105 Israel Tel. 972-8-6461725 Fax. 972-8-6472897 e-mail: [email protected] web site: http://www.bgu.ac.il/bedouin Negev Center for Regional Developmnet Ben Gurion University of the Negev P.O.B. 653 Beer Sheva 84105 Israel e-mail: [email protected] web site: http://www.bgu.ac.il/NCRD Designed and typeset by Roni Bluestein-Livnon Printed in HaMachpil LTD, Beer Sheva, Israel CONTENTS Israelis without solid ground beneath their feet: From lords of the Negev to inhabitants of a reservation 7 The 1948 upheavals 8 Displacement and expropriation 11 The State and the Bedouin lands 13 Concentrating the Bedouin in townships 15 The land question 18 1975: The Albeck Committee recommendations 20 The Bedouin put forward their own proposal for a settlement 23 1980: “The Peace Law” 24 1984: The judicial branch of government falls into line with the executive and legislative branches 26 New proposals for a settlement 28 2005: The state submits counterclaims 29 Interim summary 30 A unique and distinct civic status 32 Unique mechanisms of control 32 The military government 33 Special government committees 35 The Israel Land Administration (ILA) 37 The