The Identity of Mexican Sign As a Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

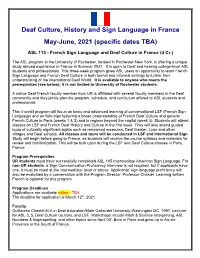

Deaf Culture, History and Sign Language in France May-June, 2021 (Specific Dates TBA)

Deaf Culture, History and Sign Language in France May-June, 2021 (specific dates TBA) ASL 113 - French Sign Language and Deaf Culture in France (4 Cr.) The ASL program at the University of Rochester, located in Rochester New York, is offering a unique study abroad experience in France in Summer 2021. It is open to Deaf and hearing college-level ASL students and professionals. This three-week program gives ASL users an opportunity to learn French Sign Language and French Deaf Culture in both formal and informal settings to further their understanding of the international Deaf World. It is available to anyone who meets the prerequisites (see below); it is not limited to University of Rochester students. A native Deaf French faculty member from UR is affiliated with several faculty members in the Deaf community and they jointly plan the program, schedule, and curriculum offered to ASL students and professionals. This 4-credit program will focus on basic and advanced learning of conversational LSF (French Sign Language) and on field trips fostering a broad understanding of French Deaf Culture and general French Culture in Paris (weeks 1 & 2) and in regions beyond the capital (week 3). Students will attend classes on LSF and French Deaf History and Culture in the first week. They will also attend guided tours of culturally significant sights such as renowned museums, Deaf theater, Lyon and other villages and Deaf schools. All classes and tours will be conducted in LSF and International Sign. Study will begin before going to France, as students will receive the course syllabus and materials for review and familiarization. -

Sign Language Endangerment and Linguistic Diversity Ben Braithwaite

RESEARCH REPORT Sign language endangerment and linguistic diversity Ben Braithwaite University of the West Indies at St. Augustine It has become increasingly clear that current threats to global linguistic diversity are not re - stricted to the loss of spoken languages. Signed languages are vulnerable to familiar patterns of language shift and the global spread of a few influential languages. But the ecologies of signed languages are also affected by genetics, social attitudes toward deafness, educational and public health policies, and a widespread modality chauvinism that views spoken languages as inherently superior or more desirable. This research report reviews what is known about sign language vi - tality and endangerment globally, and considers the responses from communities, governments, and linguists. It is striking how little attention has been paid to sign language vitality, endangerment, and re - vitalization, even as research on signed languages has occupied an increasingly prominent posi - tion in linguistic theory. It is time for linguists from a broader range of backgrounds to consider the causes, consequences, and appropriate responses to current threats to sign language diversity. In doing so, we must articulate more clearly the value of this diversity to the field of linguistics and the responsibilities the field has toward preserving it.* Keywords : language endangerment, language vitality, language documentation, signed languages 1. Introduction. Concerns about sign language endangerment are not new. Almost immediately after the invention of film, the US National Association of the Deaf began producing films to capture American Sign Language (ASL), motivated by a fear within the deaf community that their language was endangered (Schuchman 2004). -

The Guardian (UK)

9/16/2016 The race to save a dying language | Ross Perlin | News | The Guardian T he race to save a dying language The discovery of Hawaii Sign Language in 2013 amazed linguists. But as the number of users dwindles, can it survive the twin threats of globalisation and a rift in the community? by Wednesday 10 August 2016 01.00 EDT 4726 Shares 52 Comments n 2013, at a conference on endangered languages, a retired teacher named Linda Lambrecht announced the extraordinary discovery of a previously unknown language. Lambrecht – who is Chinese-Hawaiian, 71 years old, warm but no- nonsense – called it Hawaii Sign Language, or HSL. In front of a room full of linguists, she demonstrated that its core vocabulary – words such as “mother”, “pig” and I “small” – was distinct from that of other sign languages. The linguists were immediately convinced. William O’Grady, the chair of the linguistics department at the University of Hawaii, called it “the first time in 80 years that a new language has been discovered in the United States — and maybe the last time.” But the new language found 80 years ago was in remote Alaska, whereas HSL was hiding in plain sight in Honolulu, a metropolitan area of nearly a million people. It was the kind of discovery that made the world seem larger. The last-minute arrival of recognition and support for HSL was a powerful, almost surreal vindication for Lambrecht, whose first language is HSL. For decades, it was stigmatised or ignored; now the language has acquired an agreed-upon name, an official “language code” from the International Organization for Standardization, the attention of linguists around the world, and a three-year grant from the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. -

Toward a Comprehensive Model For

Toward a Comprehensive Model for Nahuatl Language Research and Revitalization JUSTYNA OLKO,a JOHN SULLIVANa, b, c University of Warsaw;a Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas;b Universidad Autonóma de Zacatecasc 1 Introduction Nahuatl, a Uto-Aztecan language, enjoyed great political and cultural importance in the pre-Hispanic and colonial world over a long stretch of time and has survived to the present day.1 With an estimated 1.376 million speakers currently inhabiting several regions of Mexico,2 it would not seem to be in danger of extinction, but in fact it is. Formerly the language of the Aztec empire and a lingua franca across Mesoamerica, after the Spanish conquest Nahuatl thrived in the new colonial contexts and was widely used for administrative and religious purposes across New Spain, including areas where other native languages prevailed. Although the colonial language policy and prolonged Hispanicization are often blamed today as the main cause of language shift and the gradual displacement of Nahuatl, legal steps reinforced its importance in Spanish Mesoamerica; these include the decision by the king Philip II in 1570 to make Nahuatl the linguistic medium for religious conversion and for the training of ecclesiastics working with the native people in different regions. Members of the nobility belonging to other ethnic groups, as well as numerous non-elite figures of different backgrounds, including Spaniards, and especially friars and priests, used spoken and written Nahuatl to facilitate communication in different aspects of colonial life and religious instruction (Yannanakis 2012:669-670; Nesvig 2012:739-758; Schwaller 2012:678-687). -

Language Resources for Spanish - Spanish Sign Language (LSE) Translation

Language Resources for Spanish - Spanish Sign Language (LSE) translation Rubén San-Segundo 1, Verónica López 1, Raquel Martín 1, David Sánchez 2, Adolfo García 2 1Grupo de Tecnología del Habla-Universidad Politécnica de Madrid 2Fundación CNSE Abstract This paper describes the development of a Spanish-Spanish Sign Language (LSE) translation system. Firstly, it describes the first Spanish-Spanish Sign Language (LSE) parallel corpus focused on two specific domains: the renewal of the Identity Document and Driver’s License. This corpus includes more than 4,000 Spanish sentences (in these domains), their LSE translation and a video for each LSE sentence with the sign language representation. This corpus also contains more than 700 sign descriptions in several sign-writing specifications. The translation system developed with this corpus consists of two modules: a Spanish into LSE translation module that is composed of a speech recognizer (for decoding the spoken utterance into a word sequence), a natural language translator (for converting a word sequence into a sequence of signs) and a 3D avatar animation module (for playing back the signs). The second module is a Spanish generator from LSE made up of a visual interface (for specifying a sequence of signs in sign-writing), a language translator (for generating the sequence of words in Spanish) and a text to speech converter. For each language translation, the system uses three technologies: an example-based strategy, a rule-based translation method and a statistical translator. collected -

What Sign Language Creation Teaches Us About Language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3

Focus Article What sign language creation teaches us about language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3 How do languages emerge? What are the necessary ingredients and circumstances that permit new languages to form? Various researchers within the disciplines of primatology, anthropology, psychology, and linguistics have offered different answers to this question depending on their perspective. Language acquisition, language evolution, primate communication, and the study of spoken varieties of pidgin and creoles address these issues, but in this article we describe a relatively new and important area that contributes to our understanding of language creation and emergence. Three types of communication systems that use the hands and body to communicate will be the focus of this article: gesture, homesign systems, and sign languages. The focus of this article is to explain why mapping the path from gesture to homesign to sign language has become an important research topic for understanding language emergence, not only for the field of sign languages, but also for language in general. © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. How to cite this article: WIREs Cogn Sci 2012. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1212 INTRODUCTION linguistic community, a language model, and a 21st century mind/brain that well-equip the child for this esearchers in a variety of disciplines offer task. When the very first languages were created different, mostly partial, answers to the question, R the social and physiological conditions were very ‘What are the stages of language creation?’ Language different. Spoken language pidgin varieties can also creation can refer to any number of phylogenic and shed some light on the question of language creation. -

General Overview of the Puerto Rican Signed Language Interpreter Katia Y

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Master's of Arts in Interpreting Studies (MAIS) Interpreting Studies Theses Spring 3-24-2017 General overview of the Puerto Rican signed language interpreter Katia Y. Rivera Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/theses Part of the Education Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Rivera, K. Y. (2017). General overview of the Puerto Rican signed language interpreter (master's thesis). Western Oregon University, Monmouth, Oregon. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/theses/34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Interpreting Studies at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's of Arts in Interpreting Studies (MAIS) Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. General Overview of the Puerto Rican Signed Language Interpreter By Katia Y. Rivera Hernández In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in Interpreting Studies Western Oregon University Signatures Redacted for Privacy ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to the amazing team of teachers I’ve had through this program. Elisa Maroney, Erin Trine, Amanda Smith, Vicki Darden, and Erica West Oyedele, you have inspired me in my academic, professional, and personal life. Thank you for believing in me and pushing me to give my best. You have been a great example to follow, and I aim to be as dedicated and kind as you have been. Elisa Maroney, my committee chair, thank you for guiding me through this process; you helped me go forward the many times I felt stuck. -

The French Belgian Sign Language Corpus a User-Friendly Searchable Online Corpus

The French Belgian Sign Language Corpus A User-Friendly Searchable Online Corpus Laurence Meurant, Aurelie´ Sinte, Eric Bernagou FRS-FNRS, University of Namur Rue de Bruxelles, 61 - 5000 Namur - Belgium [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper presents the first large-scale corpus of French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) available via an open access website (www.corpus-lsfb.be). Visitors can search within the data and the metadata. Various tools allow the users to find sign language video clips by searching through the annotations and the lexical database, and to filter the data by signer, by region, by task or by keyword. The website includes a lexicon linked to an online LSFB dictionary. Keywords: French Belgian Sign Language, searchable corpus, lexical database. 1. The LSFB corpus Pro HD 3 CCD cameras recorded the participants: one for 1.1. The project an upper body view of each informant (Cam 1 and 2 in Fig- ure 1), and one for a wide-shot of both of them (Cam 3 in In Brussels and Wallonia, i.e. the French-speaking part of Figure 1). Additionally, a Sony DV Handycam was used to Belgium, significant advances have recently been made record the moderator (Cam 4 in Figure 1). The positions of of the development of LSFB. It was officially recognised the participants and the cameras are illustrated in Figure 1. in 2003 by the Parliament of the Communaute´ franc¸aise de Belgique. Since 2000, a bilingual (LSFB-French) education programme has been developed in Namur that includes deaf pupils within ordinary classes (Ghesquiere` et al., 2015; Ghesquiere` et Meurant, 2016). -

JCR Thesis Dec 2011

PARTICIPATORY METHODS IN SOCIOLINGUISTIC SIGN LANGUAGE SURVEY: A CASE STUDY IN EL SALVADOR by Julia Ciupek-Reed Bachelor of Arts, Fresno Pacific University, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2012 This thesis, submitted by Julia Ciupek-Reed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done and is hereby approved. ___________________________________ Chair ___________________________________ ___________________________________ This thesis meets the standards for appearance, conforms to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of North Dakota, and is hereby approved. __________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School __________________________________ Date ii PERMISSION Title Participatory Methods in Sociolinguistic Sign Language Survey: A Case Study in El Salvador Department Linguistics Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my thesis work or, in his absence, by the chairperson of the department or the dean of the Graduate School. It is understood that any copying or publication or other use of this thesis or part thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Quintopozosd022.Pdf

Copyright by David Gilbert Quinto-Pozos 2002 The Dissertation Committee for David Gilbert Quinto-Pozos Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Contact Between Mexican Sign Language and American Sign Language in Two Texas Border Areas Committee: Richard P. Meier, Supervisor Susan Fischer Lisa Green Madeline Maxwell Keith Walters Contact Between Mexican Sign Language and American Sign Language in Two Texas Border Areas by David Gilbert Quinto-Pozos, B.S., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2002 Dedication To Mannie, who has been there every step of the way. Also, to my parents, Gilbert and Gloria, for their undying love and support. Acknowledgements This research has been supported by a grant (F 31 DC00352-01) from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), to the author. I am eternally grateful to many people who have contributed to this project. Without the involvement of Deaf participants, language consultants, colleagues who have discussed this work with me, and the love and support of my family and friends, this work would not have been possible. In particular, I would like to express my thanks to the Deaf participants, who graciously agreed to share samples of their language use with me. Clearly, without the willingness of these individuals to be involved in data collection, I could not have conducted this study. -

Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation Through Kinship Terminology Erin Wilkinson

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Mexico University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Linguistics ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2009 Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation through Kinship Terminology Erin Wilkinson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds Recommended Citation Wilkinson, Erin. "Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation through Kinship Terminology." (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds/40 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TYPOLOGY OF SIGNED LANGUAGES: DIFFERENTIATION THROUGH KINSHIP TERMINOLOGY BY ERIN LAINE WILKINSON B.A., Language Studies, Wellesley College, 1999 M.A., Linguistics, Gallaudet University, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Linguistics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico August, 2009 ©2009, Erin Laine Wilkinson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii DEDICATION To my mother iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many thanks to Barbara Pennacchi for kick starting me on my dissertation by giving me a room at her house, cooking me dinner, and making Italian coffee in Rome during November 2007. Your endless support, patience, and thoughtful discussions are gratefully taken into my heart, and I truly appreciate what you have done for me. I heartily acknowledge Dr. William Croft, my advisor, for continuing to encourage me through the long number of months writing and rewriting these chapters. -

Sign Language, Sign Bilingualism, and Deaf Education in Spain

THE STUDY: SIGN LANGUAGE, SIGN BILINGUALISM, AND DEAF EDUCATION IN SPAIN THEORETICAL BACKGROUND: SIGN LINGUISTICS, DEAF EDUCATION AND LANGUAGE PLANNING AIMS OF THE STUDY SIGN BILINGUAL EDUCATION: THE CONTRIBUTION OF LINGUISTICS SIGN BILINGUALISM * THE IMPLEMENTATION AND ASSESSMENT OF SIGN BILINGUAL EDUCATION SIGN BILINGUAL EDUCATION NEEDS TO BE BASED ON A CLEAR UNDERSTANDING OF SIGN BILINGUALISM. IN SPAIN * THE CONTRIBUTION OF LINGUISTICS AND ITS SUB-DISCIPLINES IS ESSENTIAL SIGN LANGUAGE TO THE SUCCESS OF SIGN BILINGUAL EDUCATION PROGRAMMES: PLANNING IMPLEMENTATION OUTCOME FUTURE * THEORETICAL LINGUISTICS: INFORMS ABOUT GRAMMATICAL PROPERTIES OF SIGN LANGUAGE TO DATE THERE IS NO SYSTEMATIC STUDY OF SIGN BILINGUALISM IN SPAIN. THE RECENT * SOCIOLINGUISTICS: IDENTIFIES THE FACTORS THAT DETERMINE IMPLEMENTATION OF SIGN BILINGUAL EDUCATION PROGRAMMES OPENS A NEW PERSPECTIVE IN THE BILINGUAL EDUCATION BILINGUALISM IN THE DEAF COMMUNITIES PATH TOWARDS BILINGUALISM IN THE DEAF COMMUNITY. IN ORDER TO ASSESS THE RESULTS OF THIS * DEVELOPMENTAL LINGUISTICS: PROVIDES CRUCIAL INSIGHTS INTO THE SIGN ORAL/ NEW OPTION IN DEAF EDUCATION A SYSTEMATIC INVESTIGATION IS NEEDED. SIGN LINGUISTICS LEARNING TASKS AND MAJOR MILESTONES IN BILINGUAL DEVELOPMENT LANGUAGE WRITTEN OUR STUDY CONCERNS THE DIFFERENT DIMENSIONS THAT ARE RELEVANT FOR A COMPREHENSIVE LANGUAGE (INCLUDING CONTACT PHENOMENA) PEDAGOGY UNDERSTANDING OF SIGN BILINGUALISM FROM A LINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE: SIGN LANGUAGE GRAMMAR, SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE DEAF COMMUNITY AND THE ACQUISITION OF THE ORAL