Viewed by the Culture of the Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bella Hadid in Elie Saab

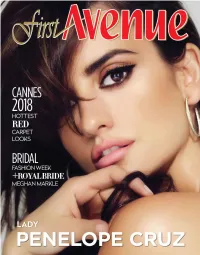

Editor’s LETTER We have weddings on the brain this issue. Not only do we have the brand new season of Bridal Fashion Week to fawn over, but a certain former First Avenue cover star only went and married herself a Prince… and we’re making pretty big deal out of it! Once you’re done with staring at pictures of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s glorious Royal Wedding, we invite you to cast your eyes over to Hollywood royalty in the form of the sparkling Cannes Film Festival red carpet. Is it just us, or do the looks get better and better each year? And that’s not all – from gushing over cover star Penelope Cruz and her glorious style, to showing you how to steal a very simple but oh so chic Burberry-heavy celeb look, it’s a jam-packed issue to say the least! Plus, keep the sun out in style with our selection of the most fashionable, statement-making sunglasses around. And we haven’t even mentioned our trendy leopard print edit yet… “Myles Mellor PENELOPE CRUZ - PAGE 38 6 CONTENTS June - July 2018 Style Crushing on… 38 Penelope Cruz Bridal Fashion Week… 12 Spring 2019 Eye Spy… 64 Stunning new season sunnies 10 38 Trend to Try… 32 Leopard print Cannes Film Festival 2018 52 Our most glamorous red carpet looks Get the Look… 10 Dove Cameron 12 52 www.firstavenuemagazine.com First Avenue Magazine @firstavenuemagazine 8 Publisher Hares Fayad Editor Myles Mellor Senior writer Maria Pierides Art Director Ahmad Yazbek Overseas Contributers Nabil Massad, Paris Kristina Rolland, Italy Samo Suleiman, Lebanon Isabel Harsh, New York Kamilia Al Osta, London Offices (U.A.E.), Dubai Jumeirah Lakes Towers, JBC 2 P.O. -

Grimm's Fairy Stories

Grimm's Fairy Stories Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm The Project Gutenberg eBook, Grimm's Fairy Stories, by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm, Illustrated by John B Gruelle and R. Emmett Owen This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Grimm's Fairy Stories Author: Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm Release Date: February 10, 2004 [eBook #11027] Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES*** E-text prepared by Internet Archive, University of Florida, Children, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Note: Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this file which includes the original illustrations. See 11027-h.htm or 11027-h.zip: (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h/11027-h.htm) or (http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/1/1/0/2/11027/11027-h.zip) GRIMM'S FAIRY STORIES Colored Illustrations by JOHN B. GRUELLE Pen and Ink Sketches by R. EMMETT OWEN 1922 CONTENTS THE GOOSE-GIRL THE LITTLE BROTHER AND SISTER HANSEL AND GRETHEL OH, IF I COULD BUT SHIVER! DUMMLING AND THE THREE FEATHERS LITTLE SNOW-WHITE CATHERINE AND FREDERICK THE VALIANT LITTLE TAILOR LITTLE RED-CAP THE GOLDEN GOOSE BEARSKIN CINDERELLA FAITHFUL JOHN THE WATER OF LIFE THUMBLING BRIAR ROSE THE SIX SWANS RAPUNZEL MOTHER HOLLE THE FROG PRINCE THE TRAVELS OF TOM THUMB SNOW-WHITE AND ROSE-RED THE THREE LITTLE MEN IN THE WOOD RUMPELSTILTSKIN LITTLE ONE-EYE, TWO-EYES AND THREE-EYES [Illustration: Grimm's Fairy Stories] THE GOOSE-GIRL An old queen, whose husband had been dead some years, had a beautiful daughter. -

The United States Of

SAAB’S BIG THE BATTLE FOR PUSH DOWNTOWN ELIE SAAB IS AMONG A WAVE OF LEBANESE DESIGNERS RAISING THEIR PROFILES IN THE WESTFIELD WORLD TRADE CENTER UNVEILS U.S. AND ABROAD. PAGE 8 ITS FIRST LIST OF TENANTS AT LAST. PAGE 3 WWDMONDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2014 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY THE UNITED STATES OF LUXURY By MILES SOCHA and SAMANTHA CONTI 16 percent; Hermès’ jumped 16.9 percent at constant exchange, and Gucci’s increased 8 percent at its own stores. AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL. The data are unequivocal: In the third quarter, the U.S. That seems to be the song luxury brands are singing these days. notched 3.5 percent growth in gross domestic product, With the Chinese market cooling and Europe in the doldrums, demonstrating broad-based improvement across the economy. the U.S. is looking more like the luxury El Dorado it used to The most recent study by Bain & Co. and Fondazione be. Simply scanning the third-quarter, or nine-month, results of Altagamma, the Italian luxury goods association, confi rmed the leading luxury brands is proof of the market’s buoyancy: Saint Americas as a key growth driver, accounting for 32 percent of a Laurent’s North American sales leaped 47 percent in the third global market for personal luxury goods estimated at 223 billion quarter; Moncler’s were up 32 percent; Brunello Cucinelli’s rose SEE PAGE 4 2 WWD MONDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2014 WWD.COM Kors’ Instagram Adds ‘Buy’ THE BRIEFING BOX most social engagement to date one of the fi rst brands to imple- IN TODAY’S WWD By RACHEL STRUGATZ — handbags, such as the Dillon ment an initiative like this. -

“Our World with One Step to the Side”: YALSA Teen's Top Ten Author

Shannon Hale “Our World with One Step to the Side”: YALSA Teen’s Top Ten Author Shannon Hale Talks about Her Fiction TAR: This quotation in the Salt Lake City Deseret News the workshopping experience is helpful because I would probably be of interest to inspiring creative learned to accept feedback on my own work, even writing majors: “Hale found the creative-writing if ultimately it didn’t take me where I want to go program at Montana to be very structured. ‘You get (it’s all for practice at that point!). As well, reading in a room with 15 people and they come at you and giving feedback on early drafts of other with razors. I became really tired of the death- people’s work was crucial for training me to be a oriented, drug-related, hopeless, minimalist, better editor of my own writing. existential terror stories people were writing.’” This What I don’t like (and I don’t think this is a seems to be the fashion in university creative writing program-specific problem) is the mob mentality programs, but it is contrary to the philosophy of that springs from a workshop-style setting. Any secondary English ed methods of teaching composi thing experimental, anything too different, is going tion classes (building a community of writers to get questioned or criticized. I found myself where the environment is trusting and risk-taking is changing what I wrote, trying to find what I encouraged as opposed to looking for a weakness thought would please my professors and col and attempting to draw blood). -

Of Magical Beings and Where to Find Them. Scripta Islandica 72/2021

Of Magical Beings and Where to Find Them On the Concept of álfar in the Translated riddarasǫgur FELIX LUMMER 1. Introduction The process of translation attempts to enable the understanding of for eign concepts and ideas, something which naturally involves the use of both words and concepts that are already extant in the receiving culture. This natu rally involves linguistic problems, but more interestingly often results in the overlapping, alteration and merging of concepts, something that can have longterm consequences on language and cultural under standing. This article aims to explore how the Old Norse mythological concept of the álfar in the Nordic countries (especially Iceland due to its preservedmanuscripts)mayhavebeenalteredthroughtheinfluenceofthe trans lation of Old French romances into Norwegian and Icelandic during the Middle Ages. As will be shown below, the mythological concept that lies behind the introduction and use of the female variant of álfar (sg. álfr) known as álfkonur (sg. álfkona) in Old Norse literature (and culture) appears to have been that of the Old French fée (pl. fées). Indeed, prior to the translation of foreign (especially Continental) works, some of which appear to have been initiated by the Norwegian King Hákon Hákonar son (1204–1263) in the early thirteenth century, the álfkona (and motifs associated with her) seem to have been mostly absent in Old Norse Lummer, Felix. 2021. Of Magical Beings and Where to Find Them: On the Concept of álfar in the Translated riddarasǫgur. Scripta Islandica 72: 5–42. © Felix Lummer (CC BY) DOI: 10.33063/diva439400 6 Felix Lummer literature and folk belief (one minor exception is, for example, Fáfnis mál st. -

Download The

The House of an Artist Recognized as one of the world’s most celebrated perfumers, Francis Kurkdjian has created over the past 20 years more than 40 world famous perfumes for fashion houses such as Dior, Kenzo, Burberry, Elie Saab, Armani, Narciso Rodriguez… Instead of settling comfortably into the beginnings of a brilliant career started with the creation of ”Le Mâle” for Jean Paul Gaultier in 1993, he opened the pathways to a new vision. He was the first in 2001 to open his bespoke fragrances atelier, going against the trend of perfume democratization. He has created gigantic olfactory installations in emblematic spaces, making people dream with his ephemeral and spectacular perfumed performances. All this, while continuing to create perfumes for world famous fashion brands and designers, as fresh as ever. Maison Francis Kurkdjian was a natural move in 2009, born from the encounter between Francis Kurkdjian and Marc Chaya, Co-founder and President of the fragrance house. Together, they fulfilled their desire for a sensual, generous and multi-facetted landscape of free expression, creating a new emblem of French know-how and lifestyle. A high-end fragrance house Maison Francis Kurkdjian’s unique personality is fostered by the creative power of a man who has a taste for precision. The Maison is guided by enchanting yet precise codes: purity, sophistication, timelessness and the boldness of a classicism reinvented. Designed in the tradition of luxury French perfumery, the Maison Francis Kurkdjian collection advocates nevertheless a contemporary vision of the art of creating and wearing perfume. Francis Kurkdjian creations were sketched like a fragrance wardrobe, with myriad facets of emotions. -

Fairy Tales on the Big and Small Screen

9 Fairy Tales on the Big and Fairy tale movies have appeal because they Small Screen provide a point of familiarity for a developing teen audience; the plot lines of by Pia Dewar modern remakes like The Brothers’ Grimm The realm of fairy tales and storytelling has (2005), or Red Riding Hood (2011) are been with us for hundreds of years. Fairy familiar to what we remember from tales have evolved over time, but have not children’s stories even though the visual lost their appeal (especially to children, and presentation and the tone can be very young adults). Fairy tales in particular have different (Kroll, 2011, p. 1). This alteration proven adaptive in the ever-growing variety to presentation has been popular, given the of media and modern movie remakes. Kroll string of popular remake movies in recent comments in his article, “studios are years as Wood notes, “modern fantasy film endlessly searching for familiar properties audiences frequently come to them first as with name recognition and spinoff children and keep returning to them potential” and with several remakes throughout adolescence and adulthood, and released in the last few years (all of which this blurs the child/adult distinctions,” are listed at the end of this article as (2006, p. 287). Beginning with the Twilight pertinent examples) this certainly seems to franchise that “put a modern twist on overly be true (2011, p. 4). Fairy tales are so familiar characters,” this shows how we are malleable, that they allow movie producers attracted to novelty with a touch of the to make motion picture remakes that are familiar (Kroll, 2011, p. -

Movies July & August

ENTERTAINMENT Pick your blockbuster! Who better to decide which movies are included in our inflight Language Selection entertainment programme than our passengers? Every month, you get to pick the blockbusters shown on English (EN), French (FR), German (DE), Dutch (NL), Italian (IT), Spanish (ES), Movies July & August Available in Business Class & Economy Class our long haul flights. Simply go to our Facebook page and cast your votes!facebook.com/brusselsairlines Portuguese (PT), Dutch subtitles (NL), English subtitles (EN) ˜ ACTION ˜ Oblivion Jack the Giant Slayer I Don’t Know The Hangover Part II ˜ DRAMA ˜ Hugo Mama Africa Ice Age: Dawn Ever After: PG PG R 13 13 PG NR A Good Day to Die Hard 125mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 114mins (2012) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL How She Does It 102 mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 42 120mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 90 mins (2011) EN, FR Of The Dinosaurs A Cinderella Story R PG PG PG PG 97 mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Tom Cruise, Morgan Freeman Ewan McGregor, Ian McShane 13 96 mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Bradley Cooper, Ed Helms 13 128 mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Ben Kingsley, Asa Butterfield Miriam Makeba 94 mins (2009) EN, FR, NL, DE, ES, IT 13 121 mins (1998) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT Bruce Willis, Jai Courtney Sarah Jessica Parker, Pierce Brosnan Chadwick Boseman, Harrison Ford Ray Romano, Denis Leary Drew Barrymore, Anjelica Huston JULY FROM JULY FROM FROM JULY ONLY AUGUST ONLY AUGUST AUGUST ONLY From Russia With Love Tomorrow Never Dies Percy -

TEACHER RESOURCE PACK for Teachers Working with Pupils in Years 4 - 6 PHILIP PULLMAN’S GRIMM TALES

PHILIP PUllMAn’S gRiMM TAlES TEACHER RESOURCE PACK FOR teachers wORKing wiTH pupilS in YEARS 4 - 6 PHILIP PUllMAn’S gRiMM TAlES Adapted for the stage by Philip Wilson Directed by Kirsty Housley from 13 nOv 2018 - 6 jAn 2019 FOR PUPILS IN SCHOOl years 4 - 6 OnCE upon A christmas... A most delicious selection of Philip Pullman’s favourite fairytales by the Brothers Grimm, re-told and re-worked for this Christmas. Enter a world of powerful witches, enchanted forest creatures, careless parents and fearless children as they embark on adventures full of magic, gore, friendship, and bravery. But beware, these gleefully dark and much-loved tales won’t be quite what you expect… Duration: Approx 2 hrs 10 mins (incl. interval) Grimm Tales For Young and Old Copyright © 2012, Phillip Pullman. All rights reserved. First published by Penguin Classics in 2012. Page 2 TEACHER RESOURCES COnTEnTS introdUCTiOn TO the pack p. 4 AbOUT the Play p. 6 MAKing the Play: interviEw wiTH director Kirsty HOUSlEY p. 8 dRAMA activiTiES - OverviEw p. 11 SEQUEnCE OnE - “OnCE UPOn A TiME” TO “HAPPILY EvER AFTER” p. 12 sequenCE TwO - the bEginning OF the story p. 15 sequenCE THREE - RAPUnZEl STORY wHOOSH p. 22 sequenCE FOUR - RAPUnZEl’S dREAM p. 24 sequenCE FivE - THE WITCH’S PROMiSES: wRiTING IN ROlE p. 26 RESOURCES FOR ACTiviTiES p. 29 Page 3 TEACHER RESOURCES INTROdUCTiOn This is the primary school pack for the Unicorn’s production of Philip Pullman’s Grimm Tales in Autumn 2018. The Unicorn production is an adaptation by Philip Wilson of Philip Pullman’s retelling of the classic fairytales collected in 19th century Germany by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. -

Folklife Sourcebook: a Directory of Folklife Resources in the United States

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 380 257 RC 019 998 AUTHOR Bartis, Peter T.; Glatt, Hillary TITLE Folklife Sourcebook: A Directory of Folklife Resources in the United States. Second Edition. Publications of the American Folklife Center, No. 14. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. American Folklife Center. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0521-3 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 172p.; For the first edition, see ED 285 813. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, P.O. Box 371954, Pittsburgh, PA 15250-7954 ($11, include stock no. S/N 030-001-00152-1 or U.S. Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-93280. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *College Programs; Cultural Education; Cultural Maintenance; Elementary Secondary Education; *Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Library Collections; *Organizations (Groups); *Primary Sources; Private Agencies; Public Agencies; *Publications; Rural Education IDENTIFIERS Ethnomusicology; *Folklorists; Folk Music ABSTRACT This directory lists professional folklore networks and other resources involved in folklife programming in the arts and social sciences, public programs, and educational institutions. The directory covers:(1) federal agencies; (2) folklife programming in public agencies and organizations, by state; (3)a listing by state of archives and special collections of folklore, folklife, and ethnomusicology, including date of establishment, access, research facilities, services, -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee. -

Working Title

Three Drops of Blood: Fairy Tales and Their Significance for Constructed Families Carol Ann Lefevre Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative Writing Discipline of English School of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide South Australia June 2009 Contents 1. Abstract.……………………………………………………………iii 2. Statement of Originality…………………………………………..v 3. Introduction………………………………………………………...1 4. Identity and Maternal Blood in “The Goose Girl”………………9 5 “Cinderella”: The Parented Orphan and the ‘Motherline’….....19 6. Abandonment, Exploitation and the Unconscious Woman in “Sleeping Beauty”………………………………………….30 7. The Adoptive Mother and Maternal Gaze in “Little Snow White”………………………………………..44 8. “Rapunzel”: The Adoptee as Captive and Commodity………..56 9. Adoption and Difference in “The Ugly Duckling”……………..65 10. Conclusion……………………………………………………...…71 11. Appendix – The Child in the Red Coat: Notes on an Intuitive Writing Process………………………………....76 12. Bibliography................................................……………………...86 13. List of Images in the Text…..……………………………………89 ii Abstract In an outback town, Esther Hayes looks out of a schoolhouse window and sees three children struck by lightning; one of them is her son, Michael. Silenced by grief, Esther leaves her young daughter, Aurora, to fend for herself; against a backdrop of an absent father and maternal neglect, the child takes comfort wherever she can, but the fierce attachments she forms never seem to last until, as an adult, she travels to her father’s native Ireland. If You Were Mine employs elements of well-known fairy tales and explores themes of maternal abandonment and loss, as well as the consequences of adoption, in a narrative that laments the perilous nature of children’s lives.