Ithaca 2018 Abstract Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wines of Chile

PREVIEWCOPY Wines of South America: Chile Version 1.0 by David Raezer and Jennifer Raezer © 2012 by Approach Guides (text, images, & illustrations, except those to which specific attribution is given) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Further, this book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This book may not be resold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Approach Guides and the Approach Guides logo are the property of Approach Guides LLC. Other marks are the prop- erty of their respective owners. Although every effort was made to ensure that the information was as accurate as possible, we accept no responsibility for any loss, damage, injury, or inconvenience sustained by anyone using this guidebook. Approach Guides New York, NY www.approachguides.com PREVIEWISBN: 978-1-936614-36-3COPY This Approach Guide was produced in collaboration with Wines of Chile. Contents Introduction Primary Grape Varieties Map of Winegrowing Regions NORTH Elqui Valley Limarí Valley CENTRAL Aconcagua Valley * Cachapoal Valley Casablanca Valley * Colchagua Valley * Curicó Valley Maipo Valley * Maule Valley San Antonio Valley * SOUTH PREVIEWCOPY Bío Bío Valley * Itata Valley Malleco Valley Vintages About Approach Guides Contact Free Updates and Enhancements More from Approach Guides More from Approach Guides Introduction Previewing this book? Please check out our enhanced preview, which offers a deeper look at this guidebook. The wines of South America continue to garner global recognition, fueled by ongoing quality im- provements and continued attractive price points. -

Peter Richards MW on Chile for Imbibe

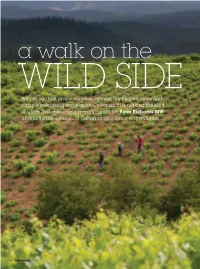

a walk on the WILD SIDE With its oddball grape varieties, ancient dry-farmed vines and funky winemaking techniques, Chile’s south is making the kind of wines that restaurants are crying out for. Peter Richards MW abandons the comforts of Cabernet Sauvignon to investigate 64 imbibe.com Chile2.indd 64 4/23/2015 4:15:29 PM SOUTHERN CHILE MAIN & ABOVE: EXPLORING THE VINEYARDS OF ITATA. FAR RIGHT: HARVEST TIME AT GARCIA + SCHWADERER s Chile really worth the effort? It’s out via Carmenère, Pinot Noir and Syrah. host of other (often unidentifi ed) varieties a question – often expressed as a Yet still, the perception persists of a grew on granite soils amid rolling hills Iresigned reaction – that is fairly country that delivers solid, maybe ever- and a milder, more temperate climate widespread in the on-trade. Perhaps improving wines but which neither make than warmer areas to the north. it’s understandable, given how many the fi nest partners for food, nor have the The hills around the port city of brilliant wines from all over the globe capacity to get people excited – be they Concepción are considered Chile’s longest vie for attention in our bustling and sommeliers or diners. established vineyard, and it’s a sobering colourful marketplace, including tried This, of course, begs the question: thought that, given it was fi rst developed and tested favourites. what does get people excited when it in the mid- to late-16th century by Jesuit But it’s also based on a missionaries, this area has more conception of Chile as somewhat winemaking history than the predictable and limited in both great estates of the Médoc. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

Talking About Wine 11

11 Talking about wine 1 Put the conversation in the correct order. a 1 waiter: Would you like to order some wine with your meal? b woman: Yes, a glass of Pinot Grigio, please. c waiter: The Chardonnay is sweeter than the Sauvignon Blanc. d man: We’d like two glasses of red to go with our main course. Which is smoother, the Chianti or the Bordeaux? e waiter: Well, they are both excellent wines. I recommend the Bordeaux. It’s more full-bodied than the Chianti and it isn’t as expensive. f man: Yes, please. Which is sweeter, the Chardonnay or the Sauvignon Blanc? g man: Right. I’ll have a glass of Chardonnay, then. Sarah, you prefer something drier, don’t you? h man: OK then, let’s have the Bordeaux. i waiter: Certainly, madam. And what would you like with your main course? j woman: Yes, a bottle of sparkling water, please. k waiter: Thank you, sir. Would you like some mineral water? l 12 waiter: OK, so that’s a glass of Chardonnay, a glass of Pinot Grigio, two glasses of Bordeaux and a bottle of sparkling mineral water. 2 Find the mistakes in each sentence and correct them. 1 The Chilean Merlot is not more as expensive as the French. 2 The Riesling is sweet than the Chardonnay. 3 The Pinot Grigio is drier as the Sauvignon Blanc. 4 Chilean wine is most popular than Spanish. 5 A Chianti is no as full-bodied as a good Bordeaux. 6 Champagne is more famous the sherry. -

Italian Wine Spanish Wine Chilean Wine

I T A L I A N W I N E Tere Nere Brunello -750ml Ilpumo Primitivo -750ml Tere Di Bio Barbaresco -750ml Casata Parini Montepulciano -750 ml Neirano Barolo -750ml Gorotti Sangiovese Merlot - 750ml Argano Toscana -750ml Primaverina Rosso -750ml Borgo Bella Toscana -750ml Nine 17 Sangiovese -750ml Barone Montalto -750ml Barone Ricasoli Chianti - 750ml Brico Al Sole Montepulciano -750ml Sermann Pinot Grigio -750ml Castorani Montepulciano -750ml Oko Organic Pinot Grigio -750 ml Terranosta Primitivo -750ml S P A N I S H W I N E La Maltida Rioja -750ml Castilo De Fuente Monastrell -750ml Lan Rioja -750ml Broken Ass Red Blend -750ml Sin Complejos Rioja -750ml Gran Vinaio -750ml Terra Unica Tempranillo -750ml Honoro Vera Granacha -750ml Miyone Granacha -750ml Xenys Monastrell -750ml Taja Monastrell -750ml Altos Rosal -750ml Campo Viejo Rioja -750ml Foresta Sauvignon Blanc -750ml C H I L E A N W I N E Toro De Piedra Cabernet Sauvignon 2015 -750ml Casa Del Toro Pinot Noir 2018 -1750 ml & 750ml Casa Del Toro Cabernet Sauvignon 1750 ml & 750ml Lanzur Merlot 2017 -750ml Lanzur Shiraz 2015 -750ml Sassy Chardonnay 2016 -750ml Sassy Merlot 2016 -750ml Layla Merlot 2015 -750ml Don Tony Perez Chardonnay -750ml Layla Chardonnay -750ml Marchigue Gran Reserva -750ml Puerto Viejo Merlot - 750ml F R E N C H W I N E Chateau Bellevue Bordeaux 2018 - 750ml Chateau De Lavagnac Bordeaux 2016 -750ml Cotes Du Rhone Loiseau 2017 -750ml Macon Vilages Mommessin 2013 -750ml Chateauneuf-Du- Pape E. Chambellan 2016 -750ml Guigal Hermitage -750ml Beaujolais- Villages Vieilles Vignes 2019 -750ml Magali Mathray Fleurie 2015 -750ml Cotes -Du _ Rhone Bonpass -750ml Bourgogne Grand Ordinare 2014 -750 ml Beaujolais - Villages Chameroy L. -

HLSR Rodeouncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results

HLSR RodeoUncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region Grand Champion Best of Show, Marchesi Antinori Srl Guado al Tasso, Bolgheri DOC Superiore, 2009 Old World Bordeaux-Blend Red Double-Gold Italy Class Champion Reserve Grand Champion, Class Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards Estate Bottled Pinot Noir, Russian River New World Pinot Noir ($23-$35) Double-Gold U.S. Champion Valley, 2010 Top Texas, Class Champion, Bending Branch Winery Estate Grown Tannat, Texas Hill Country, 2011 Tannat Double-Gold Texas Texas Class Champion Top Chilean, Class Champion, Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon ($16 and La Playa Vineyards Axel Cabernet Sauvignon, Colchagua Valley, 2011 Double-Gold Chile Chile Class Champion higher) Top Red, Class Champion Fess Parker Winery The Big Easy, Santa Barbara County, 2011 Other Rhone-Style Varietals/Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top White, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling, Finger Lakes, 2011 Riesling - Semi-Dry Double-Gold U.S. Top Sparkling, Class Champion Sophora Sparkling Rose, New Zealand, NV Sparkling Rose Double-Gold New Zealand Top Sweet, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling Ice Wine, Finger Lakes, 2010 Riesling-Sweet Double-Gold U.S. Top Value, Class Champion Vigilance Red Blend " Cimarron", Red Hills Lake County, 2011 Cab-Syrah/Syrah-Cab Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top Winery Michael David Winery Top Wine Outfit Trinchero Family Estates Top Chilean Wine Outfit Concha Y Toro AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region 10 Span Chardonnay, Central Coast, California, 2012 Chardonnay wooded ($10 -$12) Silver U.S. 10 Span Pinot Gris, Monterey, California, 2012 Pinot Gris/Pinot Grigio ($11-$15) Silver U.S. -

Chilean Whites

CHILE Chilean whites: ‘The important thing on the up is sticking to your guns and following what you Breaking free from Chile’s long association with red wines, the country’s winemakers are going to extremes to find a greater believe in’ Rafael Tirado, Laberinto diversity of terroir, in a quest for enhanced complexity and quality in their white wines, as Peter Richards MW reports emerging, which is much more diverse and interesting. This new Chile will produce more white wines.’ A path less trodden Chile’s best white wines are all about extremes. The country’s top white producers have left the comfort zone of the Central Valley and climbed high into the Andes foothills, struck out for the coast, or headed south in search of cooler, more marginal conditions and diverse soils. And it’s not just about points of the compass, either – it’s also about mindset. ‘Today, technology has supplanted imagination in many winemakers,’ asserts Pablo Morandé, a pioneer of Chilean whites who originally developed Casablanca and now produces mould-breaking wines at Bodegas Re. ‘But to make great whites, you need to be absolutely free with your winemaking.’ The southern extremities of Chilean wine country are producing some particularly exciting whites, often majoring on brisk acidity and restrained, ageworthy characteristics. SoldeSol is an excellent line of wines made at Viña Aquitania in the Traiguén area of Malleco, by thoughtful winemaker Felipe de Solminihac. ‘People know Chile as a warm country, a red wine producer,’ muses de Solminihac. ‘But SoldeSol wines are different, even from other IMAGine THE Scene. -

Sparkling Wine

N ITALIA KITCHEN WINE selection ITALY Italy is home to some of the oldest wine-producing regions in the world, and Italian wines are known worldwide for their broad variety. Italy, closely followed by France, is the world’s largest wine producer by volume. Its contribution is about 45–50 million hl per year, and represents about 1/3 of global production. Italian wine is exported around the world and is also extremely popular in Italy: Italians rank fifth on the world wine consumption list by volume with 42 litres per capita consumption. Grapes are grown in almost every region of the country and there are more than one million vineyards under cultivation. Wikipedia contributors. “Italian wine.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 17 Jun. 2017. Web. 18 Jul. 2017 Italian wines Gabbiano | Chianti DOCG 895 The Gabbiano Chianti DOCG is a deep ruby red color in the glass, while the nose exhibits floral aromas of violets and a ripe array of red wild berries. The dry, full-bodied palate is perfectly balanced with flavors that echo the nose. The tannins are sweet, smooth and mouth-filling, and the finish is clean. Our recommended pairings: great with your favorite pasta, pizza dish Gabbiano | Chianti Classico DOCG 1,200 Brilliant ruby red color accented by aromas of cherry, red berries and plum. Well-balanced palate full of ripe red fruit notes, highlighted by round, persistent tannins and a long, intense finish. Our recommended pairings: great with most pomodoro base pasta, steak, Salpicao, Osso Buco, pizza Fantini Farnese | Montepulciano D’Abruzzo 895 Plum, cranberry, little strawberry. -

Vinoetceterajanuary 2020 MAGAZINE | WINE | TRAVEL | COMMUNITY | FOOD | TRENDS

vinoetceteraJANUARY 2020 MAGAZINE | WINE | TRAVEL | COMMUNITY | FOOD | TRENDS HOLA SOUTH AMERICA EDITORIAL New Year | New Decade Zoé Cappe, Editor-in-Chief Argentina is a country of altitudes, while Chile is all about latitudes. The two wine giants from South America MASTER PIECE are as dynamic as ever. New wine regions have been emerging and producing great wines. Find out Go Organic? | One why Opimian’s new Argentinian Size Does Not Fit All producers, Finca Ferrer and Bodegas los Toneles, Jane Masters MW is Opimian’s Master of Wine chose to grow vines in this beautiful country. Continue your South American journey with asado, Argentina’s best-known barbecue dish, and discover how Quebecer Wayne McGurk came to be an Opimian member. Jane Masters MW tells us all about organic wine, a trend that is here to stay. But are organic wines really harmless? Our new feature, Wine Tips, gives you advice and tips on what truly matters: wine! Find out how weather can affect a vintage on page 10. As wine drinkers, we increasingly desire not only Here’s to 2020—happy reading! wines that taste great, but ones that also fit within a healthy lifestyle. Wine producers want to consider the land they farm, protect their families and wildlife from chemical sprays, and encourage biodiversity. But are the good intentions all they are cracked up to be? And if so, why aren’t all wine producers going organic? In the 1970s, vine growers started to notice the negative impact the heavy use of agrochemicals was having on their soils. -

Chile Wine Brief 2013 by Peter Richards MW

PETER RICHARDS MW ISSUE 01 : 2013 CHILE WINE BRIEF PETER RICHARDS MW CONTENTS Introduction 02 Talking points 04 Facts AND figures 09 Grape varieties 13 Regions 17 2013 vintage report 22 Producer rankings AND REVIEwS 24 WiNE RATINGS 35 a-z summary of wine ratings 47 ILLUSTRATION by HELEN RICHARDS ISSUE 01 : 2013 01 intro- CHILE I’ve been captivated by personal. It’s therefore Chile since working inevitably limited and duc- WINE as a journalist there in somewhat homespun – tion BRIEF the late 1990s, when I but hopefully this is what started covering the wine makes it worthwhile scene. I’ve visited almost too. It is intended for annually since, to keep everyone from producers up to date (and enjoy to the global wine trade some proper pisco sours). to students and everyday A book (The Wines of wine lovers: anyone with Chile), a Master of Wine an interest in being ahead Dissertation, thousands of the curve and enjoying of wines and words later, delicious Chilean wine. and I still can’t dance the The design and marketing cueca. But I do have a feel is deliberately different, ‘Chile lies at for Chilean wine in the as is my approach to global context – hence my rating wines, for reasons opening remarks. I outline in that section. The idea is to make this the end of Consider this document a regular publication, to like a peek behind keep up with the rapid the scenes of Chilean pace of change in Chilean wine: a well informed wine. all roads’ briefing dossier that brings you bang up to I very much hope you THE AUTHOR date with all the latest enjoy it. -

A Chilean Wine Primer the ‘Global Financial Crisis’ Has Not Stopped People from Enjoying Wine, but It Has Made Many People More Price- Sensitive

First published online at www.nicks.com.au Chile's geography is amongst the most spectacular in the world. Its wines are fast catching up to the scenery. Above: Arboleda's vineyards in the Aconcagua Valley. A Chilean Wine Primer The ‘Global Financial Crisis’ has not stopped people from enjoying wine, but it has made many people more price- sensitive. Reports from retailers, restauranteurs and industry analysts indicate that consumers are buying as much wine as they did a year ago, though they’re spending much less. Naturally, the big beneficiaries are those that can offer outstanding wines at bargain prices. Chile is one of these. The last five or six vintages have been very good, with many believing that the 2007 vintage reds will surpass the exceptional 2005 and 2003 vintages in quality. As challenging as this might make things for Australian and New Zealand producers, it presents an opportunity for Chilean wines to move up the scale in price and prestige, and enter the middle segment of the market, at least so long as Chile’s winemakers can resist the temptation to return to the ‘bargain basement’. With land and labour costs still far below those of ‘premier’ regions like Bordeaux or the Barossa, Chilean winemakers have known for some time that if they can focus on quality, they can over-deliver at almost any price point. The perception of Chile as a producer solely of inexpensive but pleasant, value for money wines has been difficult to shrug off. It was abruptly skewed with the release of Eduardo Chadwick’s ‘Sena’ in 1995. -

Brotherhood America's Oldest Winery

Brotherhood Team Pictured L-R: Hernan Donoso, Bob Barrow, Daniel Alcorso, Philip Dunsmore & Mark Daigle. Written By Allison Levine inemaking in the United States dates native grapes in 1809 in the backyard of his Emerson continued to sell wines branded Wback to the early 1800s. Today, almost shoe store. Under the label “Blooming Grove as the “Finest Medicinal and Sacramental 175 years later, located in Washingtonville, Winery,” he produced wine for sacramental Wines in America.” During the thirteen New York (an hour north of Manhattan), use. In 1863 Jaques passed the winery on to years of Prohibition, Brotherhood contin- Brotherhood Winery, America’s oldest win- his sons who renamed it the “Jaques Brothers’ ued operation, maintaining its vineyards and ery, is still producing wine. From sacramental Winery.” A few years later, wine merchant coast-to-coast distribution. After Prohibition, wines to commercial production, Brother- J.M. Emerson & Son purchased the winery the Farrell family took over the winery and hood Winery is the oldest continuing winery and renamed it “Brotherhood Wine Com- ran it until 1987. During the period between in the United States. pany.” Prohibition and 1987, Brotherhood also Brotherhood Winery was first established Prohibition was enacted in 1919 and became a tourist destination, drawing thou- in 1839 by Jean Jaques who began growing while most American wineries shut down, sands of guests annually to visit the under- 18 BIN 2013 ground cellars, the wine production and the Brotherhood continues to produce the Grand Monarque catering hall, to the mod- picturesque site. traditional wines, such as Holiday Spice, May ern wine production facility, Brotherhood is a In 1987, Brotherhood Winery was pur- wine and Rosario, but their main focus is journey from the past to the present.