Museum of New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century

Hannigan 1 “Overrun All This Country…” Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century “José Francisco Chavez.” Library of Congress website, “General Nicolás Pino.” Photograph published in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, The History of the Military July 15 2010, https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/congress/chaves.html Occupation of the Territory of New Mexico, 1909. accessed March 16, 2018. Isabel Hannigan Candidate for Honors in History at Oberlin College Advisor: Professor Tamika Nunley April 20, 2018 Hannigan 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2 I. “A populace of soldiers”, 1819 - 1848. ............................................................................................... 10 II. “May the old laws remain in force”, 1848-1860. ............................................................................... 22 III. “[New Mexico] desires to be left alone,” 1860-1862. ...................................................................... 31 IV. “Fighting with the ancient enemy,” 1862-1865. ............................................................................... 53 V. “The utmost efforts…[to] stamp me as anti-American,” 1865 - 1904. ............................................. 59 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 72 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 87 Number 3 Article 4 7-1-2012 Boots on the Ground: A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley James Blackshear Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Blackshear, James. "Boots on the Ground: A History of Fort Bascom in the Canadian River Valley." New Mexico Historical Review 87, 3 (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol87/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Boots on the Ground a history of fort bascom in the canadian river valley James Blackshear n 1863 the Union Army in New Mexico Territory, prompted by fears of a Isecond Rebel invasion from Texas and its desire to check incursions by southern Plains Indians, built Fort Bascom on the south bank of the Canadian River. The U.S. Army placed the fort about eleven miles north of present-day Tucumcari, New Mexico, a day’s ride from the western edge of the Llano Estacado (see map 1). Fort Bascom operated as a permanent post from 1863 to 1870. From late 1870 through most of 1874, it functioned as an extension of Fort Union, and served as a base of operations for patrols in New Mexico and expeditions into Texas. Fort Bascom has garnered little scholarly interest despite its historical signifi cance. -

Edmund G. Ross As Governor of New Mexico Territory: a Reappraisal

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 36 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-1961 Edmund G. Ross as Governor of New Mexico Territory: A Reappraisal Howard R. Lamar Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Lamar, Howard R.. "Edmund G. Ross as Governor of New Mexico Territory: A Reappraisal." New Mexico Historical Review 36, 3 (1961). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol36/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW VOL. XXXVI JULY, 1961 No.3 EDMUND G. ROSS AS GOVERNOR OF NEW MEXICO TERRITORY A REAPPRAISAL By HOWARD R. LAMAR NE evening in the early spring of 1889, Edmund G. Ross O invited the Territorial Secretary of New Mexico, George W. Lane, in for a smoke by a warm fire. As they sat in the family living quarters of the Palace of the Governors and talked over the'day's events, it became obvious that the Gov- , ernor was troubled about something. Unable to keep still he left his chair and paced the floor in silence. Finally he re marked: "I had hoped to induct New Mexico into Statehood."1 In those few words Ross summed up all the frustrations he had experienced in his four tempestuous years as the chief executive of New Mexico Territory. , So briefly, or hostilely, has his career as governor been re ported-both in the press of his own time and in the standard histories of New Mexico-and so little legislation is associated with his name, that one learns with genuine surprise that he had been even an advocate of statehood. -

NPS Form 10 900-B

NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet DRAFT 8/31/2012 Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail Section number G Page 136 GEOGRAPHICAL DATA The geographical data presented provide an important basis for interpreting and understanding the historic resources of the Santa Fe Trail. Establishing the course of the trail and the physical and cultural environment over which it extended are of primary importance. Ideally, such geographical data should encompass a description of the trail and all its branches. An understanding of the physiographic regions through which the trail passes allows a better appreciation of the ease or difficulty of movement across the trail. Relatively level areas provided ease of wagon movement while areas like Raton Pass presented considerable obstacles. The climate also presented challenges ranging from infrequent precipitation over sections of the Cimarron Route to abundant thunderstorms along other portions of the trail. The climate also contributed to other physical processes which molded the landscape, including mechanical and chemical weathering and erosion. The spatial and temporal variations in the physical environment clearly entered into the decision-making process of the Santa Fe Trail traveler. Since many of the historic resources presented in this nomination deal with elements of the physical landscape, an understanding of the resources’ physical and cultural emergence is needed. For the purposes of identification and interpretation, even their physical appearance bears much importance. Vegetation and soils provide an epidermis for the physical landscape, and in doing so, often hide the remains of resources important to a better understanding of the trail. -

NPS Form 10 900-B

NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) Section number Appendices Page 159 ADDITIONAL DOCUMENTATION Figure 1. William Buckles, “Map showing official SFT Routes…,” Journal of the West (April 1989): 80. Note: The locations of Bent’s Old Fort and New Fort Lyon are reversed; New Fort Lyon was west of Bent’s Old Fort. NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) Section number Appendices Page 160 Figure 2. Susan Calafate Boyle, “Comerciantes, Arrieros, Y Peones: The Hispanos and the Santa Fe Trade,” Southwest Cultural Resources Center: Professional Papers No. 54: Division of History Southwest Region, National Park Service, 1994 [electronic copy on-line]; available from National Park Service, <http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/safe/shs3.htm> (accessed 11 August 2011). NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) Section number Appendices Page 161 Figure 3. “The Southwest 1820-1835,” National Geographic Magazine, Supplement of the National Geographic November 1982, 630A. NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. -

1892 Southern Pacific New Mexico

Poole Brothers: The Correct Map of Railway and Steamship Lines Operated by the Southern Pacific Company 1892 11 10 9 8 6 5 7 3 4 2 Rumsey1 Collection Image Number 3565144 - Terms of Use 1: Southern Pacific Company 1870 William Emory noted the route that a southern transcontinental railroad must follow, while he surveyed the boundary between the U.S. and Mexico. No matter which boundary line determined by the the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was correct, neither included this route, and so the U.S. purchased an additional chunk from Mexico, adding New Mexico's distinctive "bootheel". The Gadsden Purchase paved the way for the Southern Pacific Railway Company to build its transcontinental line through southern New Mexico. This bill gave hundreds of thousands of acres of land in New Mexico, sales of which were to generate revenue, to the Southern Pacific Railway Company, as well as generous giveaways of mineral and timber. In order to move real estate in what had been viewed as the "Great American Desert," and which was indeed still a wild west frontier, Southern Pacific created Sunset Magazine, to promote the idyllic life a venturesome homesteader could find out west. 04 April 1870 Senate Bill ...Whereas the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, (of Texas,) a company duly organized and established by the legislature of the State of Texas, with the right of way, land grant, and chartered privileges, extending from the eastern to the western boundary lines of said State, is now building its line of railway across said State, and operating same to Hallsville, Texas: Now, therefore, in order to afford said company the right to extend its line to the Pacific Ocean, Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress Assembled, That the owners and stockholders of said Southern Pacific Railroad Company of Texas, are hereby created a body corporate and politic, by the name and title of the Southern Pacific Railway Company... -

On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of "Underdevelopment" Alyosha Goldstein

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies Faculty and Staff ubP lications American Studies 2008 On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of "Underdevelopment" Alyosha Goldstein Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_fsp Recommended Citation Comparative Studies in Society and History 2008;50(1):26-56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the American Studies at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Studies in Society and History 2008;50(1):26–56. 0010-4175/08 $15.00 # 2008 Society for Comparative Study of Society and History DOI: 10.1017/S0010417508000042 On the Internal Border: Colonial Difference, the Cold War, and the Locations of “Underdevelopment” ALYOSHA GOLDSTEIN American Studies, University of New Mexico In 1962, the recently established Peace Corps announced plans for an intensive field training initiative that would acclimate the agency’s burgeoning multitude of volunteers to the conditions of poverty in “underdeveloped” countries and immerse them in “foreign” cultures ostensibly similar to where they would be later stationed. This training was designed to be “as realistic as possible, to give volunteers a ‘feel’ of the situation they will face.” With this purpose in mind, the Second Annual Report of the Peace Corps recounted, “Trainees bound for social work in Colombian city slums were given on-the-job training in New York City’s Spanish Harlem... -

Rio Grande Project

Rio Grande Project Robert Autobee Bureau of Reclamation 1994 Table of Contents Rio Grande Project.............................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................3 Project Authorization.....................................................6 Construction History .....................................................7 Post-Construction History................................................15 Settlement of the Project .................................................19 Uses of Project Water ...................................................22 Conclusion............................................................25 Suggested Readings ...........................................................25 About the Author .............................................................25 Bibliography ................................................................27 Manuscript and Archival Collections .......................................27 Government Documents .................................................27 Articles...............................................................27 Books ................................................................29 Newspapers ...........................................................29 Other Sources..........................................................29 Index ......................................................................30 1 Rio Grande Project At the twentieth -

Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised)

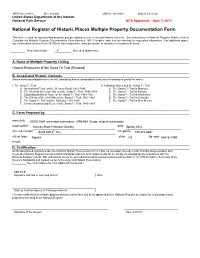

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NPS Approved – April 3, 2013 National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items New Submission X Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. The Santa Fe Trail II. Individual States and the Santa Fe Trail A. International Trade on the Mexican Road, 1821-1846 A. The Santa Fe Trail in Missouri B. The Mexican-American War and the Santa Fe Trail, 1846-1848 B. The Santa Fe Trail in Kansas C. Expanding National Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1848-1861 C. The Santa Fe Trail in Oklahoma D. The Effects of the Civil War on the Santa Fe Trail, 1861-1865 D. The Santa Fe Trail in Colorado E. The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad, 1865-1880 E. The Santa Fe Trail in New Mexico F. Commemoration and Reuse of the Santa Fe Trail, 1880-1987 C. Form Prepared by name/title KSHS Staff, amended submission; URBANA Group, original submission organization Kansas State Historical Society date Spring 2012 street & number 6425 SW 6th Ave. -

The Last Conquistador” a Film by John J

Delve Deeper into “The Last Conquistador” A film by John J. Valadez & Cristina Ibarra This multi-media resource list, John, Elizabeth Ann Harper. Riley, Carroll L. Rio del Norte: compiled by Shaun Briley of the Storms Brewed in Other Men's People of the Upper Rio Grande San Diego Public Library, Worlds: The Confrontation of from the Earliest Times to the provides a range of perspectives Indians, Spanish, and French in Pueblo Revolt. Salt Lake City: on the issues raised by the the Southwest, 1540-1795. University of Utah Press, 1995. upcoming P.O.V. documentary Norman, OK: University of A book about Pueblo Indian culture “The Last Conquistador” that Oklahoma Press, 1996. John and history. premieres on July 15th, 2008 at describes the Spanish, the French, 10 PM (check local listings at and American colonization spanning Roberts, David. The Pueblo www.pbs.org/pov/). from the Red River to the Colorado Revolt: The Secret Rebellion Plateau. That Drove the Spaniards Out of Renowned sculptor John Houser has the Southwest. New York: a dream: to build the world’s tallest Kammen, Michael. Visual Shock: Simon & Schuster, 2004. Roberts bronze equestrian statue for the city A History of Art Controversies in describes the Pueblo revolt of 1680, of El Paso, Texas. He envisions a American Culture. New York: which resulted in a decade of stunning monument to the Spanish Vintage, 2007. Pulitzer Prize independence before the Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate that winner Kammen examines how reasserted dominion over the area. will pay tribute to the contributions particular pieces of public art in Hispanic people made to building America’s history have sparked Schama, Simon.