ANIMAL POETICS in LITERARY MODERNISM By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT of GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected]

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected] POSITIONS Bowdoin College George Taylor Files Professor of Modern Languages, 07/2017 – present Assistant (2002), Associate (2007), Full Professor (2016) in the Department of German, 2002 – present Affiliate Professor, Program in Cinema Studies, 2012 – present Chair of German, 2008 – 2011, fall 2012, 2014 – 2017, 2019 – Acting Chair of Film Studies, 2010 – 2011 Lawrence University Assistant Professor of German, 1998 – 2002 St. Olaf College Visiting Instructor/Assistant Professor, 1997 – 1998 EDUCATION Ph.D. German, Comparative Literature, University of MN, Minneapolis, 1998 M.A. German, University of WI, Madison, 1992 Diplomgermanistik University of Leipzig, Germany, 1991 RESEARCH Books (*peer-review; +editorial board review) 1. Translating the World: Toward a New History of German Literature around 1800, University Park: Penn State UP, 2018; paperback December 2018, also as e-book.* Winner of the SAMLA Studies Book Award – Monograph, 2019 Shortlisted for the Kenshur Prize for the Best Book in Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2019 [reviewed in Choice Jan. 2018; German Quarterly 91.3 (2018) 337-339; The Modern Language Review 113.4 (2018): 297-299; German Studies Review 42.1(2-19): 151-153; Comparative Literary Studies 56.1 (2019): e25-e27, online; Eighteenth Century Studies 52.3 (2019) 371-373; MLQ (2019)80.2: 227-229.; Seminar (2019) 3: 298-301; Lessing Yearbook XLVI (2019): 208-210] 2. Reading and Seeing Ethnic Differences in the Enlightenment: From China to Africa New York: Palgrave, 2007; available as e-book, including by chapter, and paperback.* unofficial Finalist DAAD/GSA Book Prize 2008 [reviewed in Choice Nov. -

Georg Trakl. Dichter Im Jahrzehnt Der Extreme

Leseprobe aus: Rüdiger Görner Georg Trakl Dichter im Jahrzehnt der Extreme Mehr Informationen zum Buch finden Sie auf www.hanser-literaturverlage.de © Paul Zsolnay Verlag Wien 2014 Rüdiger Görner Georg Trakl Dichter im Jahrzehnt der Extreme Paul Zsolnay Verlag 1 2 3 4 5 18 17 16 15 14 ISBN 978-3-552-05697-8 Alle Rechte vorbehalten © Paul Zsolnay Verlag Wien 2014 Satz: Eva Kaltenbrunner-Dorfinger, Wien Druck und Bindung: GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck Printed in Germany für Oliver Kohler Puis j’expliquai mes sophismes magiques avec l’hallucination des mots! (Dann erklärte ich mir meine magischen Sophismen mit der Halluzination der Worte!) Arthur Rimbaud, Délires (1872/73) Die Gegenwart oktroyiert Formen. Diesen Bannkreis zu überschreiten und andere Formen zu gewinnen, ist das Schöpferische. Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Buch der Freunde (1922) Das Wort des Dichters macht die Dinge schwebend […] Das ist der wahre Rhythmus des Gedichts: daß es das Ding hinträgt zum Menschen, aber daß es zugleich das Ding wieder zurückschweben läßt zum Schöpfer. Max Picard, Wort und Wortgeräusch (1963) Das Böse und das Schöne sind die beiden Heraus- forderungen, die wir annehmen müssen. François Cheng, Meditationen über die Schönheit (2008) Inhalt Vorworthafter Dreiklang . 11 Tagebucheintrag 11 – Zugänge zu Trakl 14 – … und ein einleitendes de profundis 17 Finale Anfänge: Die Sammlung 1909 . 33 Lyrische Stimmungsumfelder 45 – Die Sammlung 1909 oder Das Unverlorne meiner jungen Jahre 52 »Im Rausch begreifst du alles.« Trakls toxisches Schaffen . 64 Entgrenzungsversuche: Wien – Innsbruck – Venedig – Berlin oder Ist überall Salzburg? . 80 Trakls Salzburg-Gedichte 89 – Ein politischer Trakl? 113 Gedichte, 1913 . .. 121 Vorklärungen 121 – Gedichte oder Romanzen mit Raben und Ratten 127 Poetische Farbwelten oder Schwierigkeiten mit dem (lyrischen) Ich . -

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples Mittelalter (1150- Wolfram von Eschenbach Epik Parzival (1200/1210) 1450) Gottfried von Straßburg Tristan (ca. 1210) Hartmann von Aue Der arme Heinrich (ca. 1195) Johannes von Tepl Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (ca. 1400) Walther von der Vogelweide Lieder, Oskar von Wolkenstein Minnelyrik, Spruchdichtung Gedichte Renaissance Martin Luther Prosa Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) (1400-1600) Von der Freyheit eynis Christen Menschen (1521) Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) Das Volksbuch vom Eulenspiegel (1515) Der ewige Jude (1602) Sebastian Brant Das Narrenschiff (1494) Barock (1600- H.J.C. von Grimmelshausen Prosa Der abenteuerliche Simplizissimus Teutsch (1669) 1720) Schelmenroman Martin Opitz Lyrik Andreas Gryphius Paul Fleming Sonett Christian v. Hofmannswaldau Paul Gerhard Aufklärung (1720- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Prosa Fabeln 1785) Christian Fürchtegott Gellert Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Drama Nathan der Weise (1779) Bürgerliches Emilia Galotti (1772) Trauerspiel Miss Sara Samson (1755) Lustspiel Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück (1767) 2 Sturm und Drang Johann Wolfgang Goethe Prosa Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) (1767-1785) Johann Gottfried Herder Von deutscher Art und Kunst (selections; 1773) Karl Philipp Moritz Anton Reiser (selections; 1785-90) Sophie von Laroche Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771/72) Johann Wolfgang Goethe Drama Götz von Berlichingen (1773) Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz Der Hofmeister oder die Vorteile der Privaterziehung (1774) -

Staging Memory: the Drama Inside the Language of Elfriede Jelinek

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 31 Issue 1 Austrian Literature: Gender, History, and Article 13 Memory 1-1-2007 Staging Memory: The Drama Inside the Language of Elfriede Jelinek Gita Honegger Arizona State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the German Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Honegger, Gita (2007) "Staging Memory: The Drama Inside the Language of Elfriede Jelinek," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 31: Iss. 1, Article 13. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1653 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Staging Memory: The Drama Inside the Language of Elfriede Jelinek Abstract This essay focuses on Jelinek's problematic relationship to her native Austria, as it is reflected in some of her most recent plays: Ein Sportstück (A Piece About Sports), In den Alpen (In the Alps) and Das Werk (The Plant). Taking her acceptance speech for the 2004 Nobel Prize for Literature as a starting point, my essay explores Jelinek's unique approach to her native language, which carries both the burden of historic guilt and the challenge of a distinguished, if tortured literary legacy. Furthermore, I examine the performative force of her language. Jelinek's "Dramas" do not unfold in action and dialogue, rather, they are embedded in the grammar itself. -

Poetry, Poetics and the Spiritual Life

Theological Trends POETRY, POETICS AND THE SPIRITUAL LIFE Robert E. Doud Y THOUGHTS HERE have mostly to do with appreciating the M dynamics of theology and spirituality as analogous to the dynamics of poetry. They flow from meditations on the poetic ideas of the philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), and they reflect some aspects of the theology of Karl Rahner (1904–1984) as well. Poetics is the theory of poetry; and it is connected with philosophical issues concerning language, expression and communication as basic prerogatives and possibilities of human beings. For Heidegger, poetry is not a late-emerging use of language to embellish direct expression, but rather constitutes the original basis of language in the way humans complete the natural world by giving things names and descriptions. Heidegger saw poetic or meditative thought as the chief prerogative of the human mind and the chief means of finding and achieving fulfilment for human beings. But Heidegger also perceived that the prevailing values of the modern world were inimical to this fulfilment. Exploring the implications of a poem or of a verse in scripture may seem to be a waste of time in a culture where material needs compete urgently for time with spiritual rest and growth. Parents need to build a home and acquire temporal goods, while managers need to hire efficient people, keep down costs and show profits. Moreover we live in a time when the reality of technology needs continuously to be faced and evaluated. The use of technology is advancing, and while it brings progress and success, it also threatens to take the control of many things out of the hands of human beings, who ought to be free to write their own destiny. -

I Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity Through the Oeuvre of Strauss And

Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity through the Oeuvre of Strauss and Hofmannsthal by Solveig M. Heinz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Germanic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Vanessa H. Agnew, Chair Associate Professor Naomi A. André Associate Professor Andreas Gailus Professor Julia C. Hell i For John ii Acknowledgements Writing this dissertation was an intensive journey. Many people have helped along the way. Vanessa Agnew was the most wonderful Doktormutter a graduate student could have. Her kindness, wit, and support were matched only by her knowledge, resourcefulness, and incisive critique. She took my work seriously, carefully reading and weighing everything I wrote. It was because of this that I knew my work and ideas were in good hands. Thank you Vannessa, for taking me on as a doctoral rookie, for our countless conversations, your smile during Skype sessions, coffee in Berlin, dinners in Ann Arbor, and the encouragement to make choices that felt right. Many thanks to my committee members, Naomi André, Andreas Gailus, and Julia Hell, who supported the decision to work with the challenging field of opera and gave me the necessary tools to succeed. Their open doors, email accounts, good mood, and guiding feedback made this process a joy. Mostly, I thank them for their faith that I would continue to work and explore as I wrote remotely. Not on my committee, but just as important was Hartmut. So many students have written countless praises of this man. I can only concur, he is simply the best. -

Modern Austrian Literature

MODERN AUSTRIAN LITERATURE Journal of the International Arthur Schnitzler Research Association Volume 33, Number 1, 2000 CONTENTS From the Editors..................................................................................i Acknowledgments .............................................................................. iv Contributors........................................................................................v Articles CHRISTINE ANTON Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach und die Realismusdebatte: Schreiben als Auseinandersetzung mit den Kunstansichten ihrer Zeit...............................................................1 The term "Poetic Realism” reflects the basic thrust of nineteenth-century German realist theory and its attempted synthesis of the two predominant poles of aes- thetics, Idealism and Realism. Prose narratives about artists and their creative work show the balancing act between an idealized outlook and representing em- pirical reality. This study elucidates the interrelationship of Ebner-Eschenbach’s aesthetic theory and its reflection in the literary text. AGATA SCHWARTZ Zwischen dem “noch nicht” und “nicht mehr”: Österreichische und ungarische Frauenliteratur der Jahrhundertwende ...................................................................16 This analysis of texts by selected Austrian and Hungarian women writers from around 1900 discovers an interplay of Bakhtin’s “authoritative” and “internally persuasive” discourses that elucidates the Doppelexistenz (Sigrid Weigel) of the MODERN AUSTRIAN LITERATURE -

Im Nonnengarten : an Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907 Michelle Stott Aj Mes

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Resources Supplementary Information 1997 Im Nonnengarten : An Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907 Michelle Stott aJ mes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophsupp_resources Part of the German Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation James, Michelle Stott, "Im Nonnengarten : An Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907" (1997). Resources. 2. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophsupp_resources/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Supplementary Information at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Resources by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. lm N onnengarten An Anthology of German Women's Writing I850-I907 edited by MICHELLE STOTT and JOSEPH 0. BAKER WAVELAND PRESS, INC. Prospect Heights, Illinois For information about this book, write or call: Waveland Press, Inc. P.O. Box400 Prospect Heights, Illinois 60070 (847) 634-0081 Copyright © 1997 by Waveland Press ISBN 0-88133-963-6 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 765432 Contents Preface, vii Sources for further study, xv MALVIDA VON MEYSENBUG 1 Indisches Marchen MARIE VON EBNER-ESCHENBACH 13 Die Poesie des UnbewuBten ADA CHRISTEN 29 Echte Wiener BERTHA VON -

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition <UN> Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik Die Reihe wurde 1972 gegründet von Gerd Labroisse Herausgegeben von William Collins Donahue Norbert Otto Eke Martha B. Helfer Sven Kramer VOLUME 86 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/abng <UN> Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition Edited by Lydia Jones Bodo Plachta Gaby Pailer Catherine Karen Roy LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Cover illustration: Korrekturbögen des “Deutschen Wörterbuchs” aus dem Besitz von Wilhelm Grimm; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Wilhelm Grimm’s proofs of the “Deutsches Wörterbuch” [German Dictionary]; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jones, Lydia, 1982- editor. | Plachta, Bodo, editor. | Pailer, Gaby, editor. Title: Scholarly editing and German literature : revision, revaluation, edition / edited by Lydia Jones, Bodo Plachta, Gaby Pailer, Catherine Karen Roy. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2015. | Series: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik ; volume 86 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015032933 | ISBN 9789004305441 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: German literature--Criticism, Textual. | Editing--History--20th century. Classification: LCC PT74 .S365 2015 | DDC 808.02/7--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032933 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0304-6257 isbn 978-90-04-30544-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30547-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

18 Au 23 Février

18 au 23 février 2019 Librairie polonaise Centre culturel suisse Paris Goethe-Institut Paris Organisateur : Les Amis du roi des Aulnes www.leroidesaulnes.org Coordination: Katja Petrovic Assistante : Maria Bodmer Lettres d’Europe et d’ailleurs L’écrivain et les bêtes Force est de constater que l’homme et la bête ont en commun un certain nombre de savoir-faire, comme chercher la nourriture et se nourrir, dormir, s’orienter, se reproduire. Comme l’homme, la bête est mue par le désir de survivre, et connaît la finitude. Mais sa présence au monde, non verbale et quasi silencieuse, signifie-t-elle que les bêtes n’ont rien à nous dire ? Que donne à entendre leur présence silencieuse ? Dans le débat contemporain sur la condition de l’animal, son statut dans la société et son comportement, il paraît important d’interroger les littératures européennes sur les représentations des animaux qu’elles transmettent. AR les Amis A des Aulnes du Roi LUNDI 18 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h JEUDI 21 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h LA PAROLE DES ÉCRIVAINS FACE LA PLACE DES BÊTES DANS LA AU SILENCE DES BÊTES LITTÉRATURE Table ronde avec Jean-Christophe Table ronde avec Yiğit Bener, Dorothee Bailly, Eva Meijer, Uwe Timm. Elmiger, Virginie Nuyen. Modération : Francesca Isidori Modération : Norbert Czarny Le plus souvent les hommes voient dans la Entre Les Fables de La Fontaine, bête une espèce silencieuse. Mais cela signi- La Méta morphose de Kafka, les loups qui fie-t-il que les bêtes n’ont rien à dire, à nous hantent les polars de Fred Vargas ou encore dire ? Comment s’articule la parole autour les chats nazis qui persécutent les souris chez de ces êtres sans langage ? Comment les Art Spiegelman, les animaux occupent une écrivains parlent-ils des bêtes ? Quelles voix, place importante dans la littérature. -

Georg Trakl - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Georg Trakl - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Georg Trakl(3 February 1887 - 3 November 1914) Georg Trakl was an Austrian poet. He is considered one of the most important Austrian Expressionists. <b>Life and Work</b> Trakl was born and lived the first 18 years of his life in Salzburg, Austria. His father, Tobias Trakl (11 June 1837, Ödenburg/Sopron – 1910), was a dealer of hardware from Hungary, while his mother, Maria Catharina Halik (17 May 1852, Wiener Neustadt – 1925), was a housewife of Czech descent with strong interests in art and music. Trakl attended a Catholic elementary school, although his parents were Protestants. He matriculated in 1897 at the Salzburg Staatsgymnasium, where he studied Latin, Greek, and mathematics. At age 13, Trakl began to write poetry. As a high school student, he began visiting brothels, where he enjoyed giving rambling monologues to the aging prostitutes. At age 15, he began drinking alcohol, and using opium, chloroform, and other drugs. By the time he was forced to quit school in 1905, he was a drug addict. Many critics think that Trakl suffered from undiagnosed schizophrenia. After quitting high school, Trakl worked for a pharmacist for three years and decided to adopt pharmacy as a career. It was during this time that he experimented with playwriting, but his two short plays, All Souls' Day and Fata Morgana, were not successful. In 1908, Trakl moved to Vienna to study pharmacy, and became acquainted with some local artists who helped him publish some of his poems. -

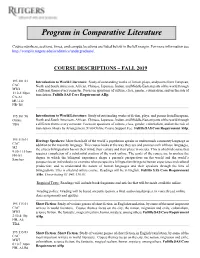

Program in Comparative Literature

Program in Comparative Literature Course numbers, sections, times, and campus locations are listed below in the left margin. For more information see http://complit.rutgers.edu/academics/undergraduate/. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS – FALL 2019 195:101:01 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, CAC North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through MW4 a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of 1:10-2:30pm translation. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. CA-A1 MU-212 HB- B5 195:101:90 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, Online North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through TBA a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of translation. Hours by Arrangement. $100 Online Course Support Fee. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. 195:110:01 Heritage Speakers: More than half of the world’s population speaks or understands a minority language in CAC addition to the majority language. This course looks at the way they use and process each of those languages, M2 the effects bilingualism has on their mind, their culture and their place in society. This is a hybrid course that 9:50-11:10am requires completion of a substantial portion of the work online. The goals of the course are to analyze the FH-A1 degree to which the bilingual experience shape a person's perspectives on the world and the world’s Sanchez perspective on individuals; to examine what perspective bilingualism brings to human experience and cultural production; and to understand the nature of human languages and their speakers through the lens of bilingualism.