Spring Ephemerals)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighborwoods Right Plant, Right Place Plant Selection Guide

“Right Plant, Right Place” Plant Selection Guide Compiled by Samuel Kelleher, ASLA April 2014 - Shrubs - Sweet Shrub - Calycanthus floridus Description: Deciduous shrub; Native; leaves opposite, simple, smooth margined, oblong; flowers axillary, with many brown-maroon, strap-like petals, aromatic; brown seeds enclosed in an elongated, fibrous sac. Sometimes called “Sweet Bubba” or “Sweet Bubby”. Height: 6-9 ft. Width: 6-12 ft. Exposure: Sun to partial shade; range of soil types Sasanqua Camellia - Camellia sasanqua Comment: Evergreen. Drought tolerant Height: 6-10 ft. Width: 5-7 ft. Flower: 2-3 in. single or double white, pink or red flowers in fall Site: Sun to partial shade; prefers acidic, moist, well-drained soil high in organic matter Yaupon Holly - Ilex vomitoria Description: Evergreen shrub or small tree; Native; leaves alternate, simple, elliptical, shallowly toothed; flowers axillary, small, white; fruit a red or rarely yellow berry Height: 15-20 ft. (if allowed to grow without heavy pruning) Width: 10-20 ft. Site: Sun to partial shade; tolerates a range of soil types (dry, moist) Loropetalum ‘ZhuZhou’-Loropetalum chinense ‘ZhuZhou’ Description: Evergreen; It has a loose, slightly open habit and a roughly rounded to vase- shaped form with a medium-fine texture. Height: 10-15 ft. Width: 10-15ft. Site: Preferred growing conditions include sun to partial shade (especially afternoon shade) and moist, well-drained, acidic soil with plenty of organic matter Japanese Ternstroemia - Ternstroemia gymnanthera Comment: Evergreen; Salt spray tolerant; often sold as Cleyera japonica; can be severely pruned. Form is upright oval to rounded; densely branched. Height: 8-10 ft. Width: 5-6 ft. -

Texas Trillium Arlington, Texas Ecological Services Field Office

U.S. FishU.S &. FishWildlife & Wildlife Service Service Texas Trillium Arlington, Texas Ecological Services Field Office Texas Trillium Trillium texanum Description Texas trillium belongs to the Liliaceae (lily) family and are rhizomatous herbs with unbranched stems. Trillium plants produce no true leaves or stems aboveground. Texas trillium has solitary white to pale pink flowers on a short stalk, situated above three bracteal leaves. It is the only trillium species in Texas with numerous stomata (specialized cells which open and close to regulate gas and water movement into/out of the plant) on Trillium pusillum var. texanum - (Photo Credit- Jason Singhurst) upper and lower surfaces of its bracts. Longevity is unknown, but one study fern (Woodwardia areolata), and showed that white trillium (Trillium green rein orchid (Platanthera grandiflorum) lives at least 30 years clavellata). based on estimates calculated from the number of constrictions on rhizomes. Conservation Although not listed as endangered or Habitat threatened by the State of Texas, Texas trillium habitat is characterized Texas trillium is ranked as a G2 by a shaded, forest understory. It (imperiled) by NatureServe and is flowers before full leaf-out of over ranked as a Sensitive Species by the story species and before being United States Forest Service. The Distribution overtopped by other herbaceous species is also listed on Texas Parks Texas trillium occurs across thirteen species. Texas trillium is found in the and Wildlife Department’s 2010 List counties in East Texas and into ecotone between riparian baygall and of the Rare Plants of Texas and as a northwestern Louisiana (Caddo sandy pine or oak uplands in the Species of Greatest Conservation Parish). -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Woodland/Shade Gardening by Jimi Blake

V OLUME 24, I SSUE 4 O CTOBER— DECEMBER 2015 Piedmont Chapter North American Rock Garden Society The Trillium Chapel Hill, Durham, Raleigh, NC Woodland/Shade Gardening By Jimi Blake Woodland plants are the brave plants that burst into flower in the spring lifting my spirit and encouraging me to start back to gardening in Hunting Brook, Co. Wicklow, Ireland. These plants are so important in the garden to extend the season of interest and brighten up a shady area. An expanse of deciduous woodland is not necessary to create a woodland garden, though it is a dream situation for this purpose but that shaded area in the corner of the garden where you dump the grass mowings can take on a whole new life, or by simply pruning a shrub to let more light under it will allow for your mini woodland garden. The other type of shade in lots of gardens is the shade creat- ed by walls, which is also suitable for growing woodland plants. In the wild, these plants flower under the dappled shade of the deciduous trees before the leaves shade out the woodland floor during the summer months. Generally the woodland plants finish flowering by early to mid sum- mer and form a ground cover of various shades of green. These plants are called spring ephemerals. Remember the secret of a good woodland garden is the preparation of the soil, as these areas can be quite dry in the summer with the roots of the trees or shrubs taking up the moisture. When I started the woodland gardens in Hunting Brook I cleared the weeds by hand and then dug over the soil and incorporated a mixture of leaf mould or garden compost, and very well rotted farmyard manure creating a delicious mixture for these woodland gems to grow well in. -

Native Plants for Conservation, Restoration & Landscaping

ABOUT THE NATIVE PLANTS FOR CONSERVATION, WHAT ARE NATIVES? For more information, refer to field guides and publications RESTORATION AND LANDSCAPING PROJECT Native species evolved within specific regions and dispersed on local natural history for color, shape, height, bloom times This project is a collaboration between the Virginia Depart- throughout their range without known human involvement. and specific wildlife value of the plants that grow in your ment of Conservation and Recreation and the Virginia Native They form the primary component of the living landscape region. Visit a nearby park, natural area preserve, forest or Plant Society. VNPS chapters across the state helped to fund and provide food and shelter for wildlife management area to learn about common plant the 2011 update to this brochure. native animal species. Native associations, spatial groupings and habitat conditions. For The following partners have provided valuable assistance plants co-evolved with specific recommendations and advice about project design, throughout the life of this project: native animals over many consult a landscape or garden design specialist with thousands to millions of experience in native plants. TheNatureConservancy–VirginiaChapter•Virginia years and have formed TechDepartmentofHorticulture•VirginiaDepartmentof complex and interdependent WHAT ARE NON-NATIVE PLANTS? AgricultureandConsumerServices•VirginiaDepartment relationships. Our native Sometimes referred to as “exotic,” “alien,” or “non- of Environmental Quality, Coastal Zone Management fauna depend on native indigenous,” non-native plants are species introduced, Program•VirginiaDepartmentofForestry•Virginia flora to provide food and DepartmentofGameandInlandFisheries•Virginia Native intentionally or accidentally, into a new region by cover. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Large-Flowered Trilliums Coming up in Spring in Our Childhoo

Large-flowered Trillium or Common Trillium (Trillium grandiflorum) Large-flowered Trilliums Coming Up in Spring In our childhood the woods in late May were full of hundreds of large, waxy white flowers that covered the forest floor. Grandma in her German diary called these trilliums “wild lilies” and also commented that on May14th and 22nd in 1927 and again on May 22nd in 1940 these flowers were numerous and in full bloom. (Freckman, 1994) gave the earliest blooming dates as April 24th. Large-flowered Trillium Bud Opening Today, with more houses and lawns in the country, and fewer undisturbed woodlots those visions of white are less frequently seen. In addition, the White-tailed Deer population has steadily increased and their appetite for tasty trilliums has served to eliminate many stands of this beautiful plant. This is especially troublesome because once the leaves and flowers are plucked, the plant is likely to die. It can no longer produce food to send down to the roots so that it can come back another year. It still grows quite abundantly on the sloping bank along Billings Avenue in the Town of Medford, Wisconsin. Some sources say that deer do not like to graze on steep banks or inclines so that may be why those plants have escaped. We have a patch of trilliums that has grown larger each year in our lawn. Recently we have had to protect these trilliums from the deer that could wipe out the entire patch in a single night. Sometimes seeds from those plants, possibly transported by ants, have grown into new plants in the front lawn. -

Ongoing Evolution in the Genus Crocus: Diversity of Flowering Strategies on the Way to Hysteranthy

plants Article Ongoing Evolution in the Genus Crocus: Diversity of Flowering Strategies on the Way to Hysteranthy Teresa Pastor-Férriz 1, Marcelino De-los-Mozos-Pascual 1, Begoña Renau-Morata 2, Sergio G. Nebauer 2 , Enrique Sanchis 2, Matteo Busconi 3 , José-Antonio Fernández 4, Rina Kamenetsky 5 and Rosa V. Molina 2,* 1 Departamento de Gestión y Conservación de Recursos Fitogenéticos, Centro de Investigación Agroforestal de Albadaledejito, 16194 Cuenca, Spain; [email protected] (T.P.-F.); [email protected] (M.D.-l.-M.-P.) 2 Departamento de Producción Vegetal, Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] (B.R.-M.); [email protected] (S.G.N.); [email protected] (E.S.) 3 Department of Sustainable Crop Production, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 29122 Piacenza, Italy; [email protected] 4 IDR-Biotechnology and Natural Resources, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 02071 Albacete, Spain; [email protected] 5 Department of Ornamental Horticulture and Biotechnology, The Volcani Center, ARO, Rishon LeZion 7505101, Israel; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Species of the genus Crocus are found over a wide range of climatic areas. In natural habitats, these geophytes diverge in the flowering strategies. This variability was assessed by analyzing the flowering traits of the Spanish collection of wild crocuses, preserved in the Bank of Plant Germplasm Citation: Pastor-Férriz, T.; of Cuenca. Plants of the seven Spanish species were analyzed both in their natural environments De-los-Mozos-Pascual, M.; (58 native populations) and in common garden experiments (112 accessions). -

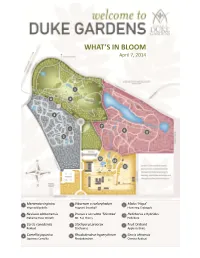

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

1Alan S. Weakley, 2Bruce A. Sorrie, 3Richard J. Leblond, 4Derick B

NEW COMBINATIONS, RANK CHANGES, AND NOMENCLATURAL AND TAXONOMIC COMMENTS IN THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES. IV 1Alan S. Weakley, 2Bruce A. Sorrie, 3Richard J. LeBlond, 4Derick B. Poindexter UNC Herbarium (NCU), North Carolina Botanical Garden, Campus Box 3280, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-3280, U.S.A. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 5Aaron J. Floden 6Edward E. Schilling Missouri Botanical Garden (MO) Dept. of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology (TENN) 4344 Shaw Blvd. University of Tennessee Saint Louis, Missouri 63110, U.S.A. Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 U.S.A. [email protected] [email protected] 7Alan R. Franck 8John C. Kees Dept. of Biological Sciences, OE 167 St. Andrew’s Episcopal School Florida International University, 11200 SW 8th St. 370 Old Agency Road Miami, Florida 33199, U.S.A. Ridgeland, Mississippi 39157, U.S.A. [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT As part of ongoing efforts to understand and document the flora of the southeastern United States, we propose a number of taxonomic changes and report a distributional record. In Rhynchospora (Cyperaceae), we elevate the well-marked R. glomerata var. angusta to species rank. In Dryopteris (Dryopteridaceae), we report a state distributional record for Mississippi for D. celsa, filling a range gap. In Oenothera (Onagraceae), we continue the reassessment of the Oenothera fruticosa complex and elevate O. fruticosa var. unguiculata to species rank. In Eragrostis (Poaceae), we address typification issues. In the Trilliaceae, Trillium undulatum is transferred to Trillidium, providing a better correlation of taxonomy with our current phylogenetic understanding of the family. -

Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1957 Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Dorothy Louise Crandall University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Crandall, Dorothy Louise, "Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1957. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Dorothy Louise Crandall entitled "Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Botany. Royal E. Shanks, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James T. Tanner, Fred H. Norris, A. J. Sharp, Lloyd F. Seatz Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) December 11, 19)7 To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by DorothY Louise Crandall entitled "Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Hountains National Park." I recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Botany. -

0118 Virginia State Flower, Tree, & Bird

VA STATE FLOWER, TREE AND BIRD The Cardinal and Dogwood Virginia's flowering dogwood has been the Crested, short-winged, long-tailed birds, official floral emblem of the state since March 1918 cardinals, are from seven and a half to nine and a when it edged out Virginia creeper by one vote. Then quarter inches long, with a wingspread of from 10 on January 25, 1950, the cardinal became the official 1/4 to 12 inches. The male is red except for a grayish state bird of Virginia. tone on the back, wings and tall and a black patch The flowering dogwood, Cornus florida, is a from the upper throat surrounding the red beak. The large shrub or small tree that usually grows from four female is olive grayish on the head and body, with a to 12 feet tall, though individual trees often attain dull red on the bill, crest, wings and tall. The bill patch much greater heights. It has very rough bark and is state colored, and the underparts are yellowish spreading branches. The wood, close grained and brown. Young cardinals resemble the female except hard, is used especially for shuttles and cogs in textile for their dark beaks. machinery and for inlaying in fine cabinet work. In March the flocks break up into mated pairs and What we speak of as the “flower” is a small nesting gets under way. The bulk), nests are loosely compact cluster of inconspicuous greenish-white true built of twigs, leaves, bark strips, rootlets, weed flowers surrounded by large showy petal-like bracts stems and grasses.