Trillium, As an Indicator of Deer Density Hanover Biodiversity Committee October, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Trillium Arlington, Texas Ecological Services Field Office

U.S. FishU.S &. FishWildlife & Wildlife Service Service Texas Trillium Arlington, Texas Ecological Services Field Office Texas Trillium Trillium texanum Description Texas trillium belongs to the Liliaceae (lily) family and are rhizomatous herbs with unbranched stems. Trillium plants produce no true leaves or stems aboveground. Texas trillium has solitary white to pale pink flowers on a short stalk, situated above three bracteal leaves. It is the only trillium species in Texas with numerous stomata (specialized cells which open and close to regulate gas and water movement into/out of the plant) on Trillium pusillum var. texanum - (Photo Credit- Jason Singhurst) upper and lower surfaces of its bracts. Longevity is unknown, but one study fern (Woodwardia areolata), and showed that white trillium (Trillium green rein orchid (Platanthera grandiflorum) lives at least 30 years clavellata). based on estimates calculated from the number of constrictions on rhizomes. Conservation Although not listed as endangered or Habitat threatened by the State of Texas, Texas trillium habitat is characterized Texas trillium is ranked as a G2 by a shaded, forest understory. It (imperiled) by NatureServe and is flowers before full leaf-out of over ranked as a Sensitive Species by the story species and before being United States Forest Service. The Distribution overtopped by other herbaceous species is also listed on Texas Parks Texas trillium occurs across thirteen species. Texas trillium is found in the and Wildlife Department’s 2010 List counties in East Texas and into ecotone between riparian baygall and of the Rare Plants of Texas and as a northwestern Louisiana (Caddo sandy pine or oak uplands in the Species of Greatest Conservation Parish). -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Woodland/Shade Gardening by Jimi Blake

V OLUME 24, I SSUE 4 O CTOBER— DECEMBER 2015 Piedmont Chapter North American Rock Garden Society The Trillium Chapel Hill, Durham, Raleigh, NC Woodland/Shade Gardening By Jimi Blake Woodland plants are the brave plants that burst into flower in the spring lifting my spirit and encouraging me to start back to gardening in Hunting Brook, Co. Wicklow, Ireland. These plants are so important in the garden to extend the season of interest and brighten up a shady area. An expanse of deciduous woodland is not necessary to create a woodland garden, though it is a dream situation for this purpose but that shaded area in the corner of the garden where you dump the grass mowings can take on a whole new life, or by simply pruning a shrub to let more light under it will allow for your mini woodland garden. The other type of shade in lots of gardens is the shade creat- ed by walls, which is also suitable for growing woodland plants. In the wild, these plants flower under the dappled shade of the deciduous trees before the leaves shade out the woodland floor during the summer months. Generally the woodland plants finish flowering by early to mid sum- mer and form a ground cover of various shades of green. These plants are called spring ephemerals. Remember the secret of a good woodland garden is the preparation of the soil, as these areas can be quite dry in the summer with the roots of the trees or shrubs taking up the moisture. When I started the woodland gardens in Hunting Brook I cleared the weeds by hand and then dug over the soil and incorporated a mixture of leaf mould or garden compost, and very well rotted farmyard manure creating a delicious mixture for these woodland gems to grow well in. -

Native Plants for Conservation, Restoration & Landscaping

ABOUT THE NATIVE PLANTS FOR CONSERVATION, WHAT ARE NATIVES? For more information, refer to field guides and publications RESTORATION AND LANDSCAPING PROJECT Native species evolved within specific regions and dispersed on local natural history for color, shape, height, bloom times This project is a collaboration between the Virginia Depart- throughout their range without known human involvement. and specific wildlife value of the plants that grow in your ment of Conservation and Recreation and the Virginia Native They form the primary component of the living landscape region. Visit a nearby park, natural area preserve, forest or Plant Society. VNPS chapters across the state helped to fund and provide food and shelter for wildlife management area to learn about common plant the 2011 update to this brochure. native animal species. Native associations, spatial groupings and habitat conditions. For The following partners have provided valuable assistance plants co-evolved with specific recommendations and advice about project design, throughout the life of this project: native animals over many consult a landscape or garden design specialist with thousands to millions of experience in native plants. TheNatureConservancy–VirginiaChapter•Virginia years and have formed TechDepartmentofHorticulture•VirginiaDepartmentof complex and interdependent WHAT ARE NON-NATIVE PLANTS? AgricultureandConsumerServices•VirginiaDepartment relationships. Our native Sometimes referred to as “exotic,” “alien,” or “non- of Environmental Quality, Coastal Zone Management fauna depend on native indigenous,” non-native plants are species introduced, Program•VirginiaDepartmentofForestry•Virginia flora to provide food and DepartmentofGameandInlandFisheries•Virginia Native intentionally or accidentally, into a new region by cover. -

Large-Flowered Trilliums Coming up in Spring in Our Childhoo

Large-flowered Trillium or Common Trillium (Trillium grandiflorum) Large-flowered Trilliums Coming Up in Spring In our childhood the woods in late May were full of hundreds of large, waxy white flowers that covered the forest floor. Grandma in her German diary called these trilliums “wild lilies” and also commented that on May14th and 22nd in 1927 and again on May 22nd in 1940 these flowers were numerous and in full bloom. (Freckman, 1994) gave the earliest blooming dates as April 24th. Large-flowered Trillium Bud Opening Today, with more houses and lawns in the country, and fewer undisturbed woodlots those visions of white are less frequently seen. In addition, the White-tailed Deer population has steadily increased and their appetite for tasty trilliums has served to eliminate many stands of this beautiful plant. This is especially troublesome because once the leaves and flowers are plucked, the plant is likely to die. It can no longer produce food to send down to the roots so that it can come back another year. It still grows quite abundantly on the sloping bank along Billings Avenue in the Town of Medford, Wisconsin. Some sources say that deer do not like to graze on steep banks or inclines so that may be why those plants have escaped. We have a patch of trilliums that has grown larger each year in our lawn. Recently we have had to protect these trilliums from the deer that could wipe out the entire patch in a single night. Sometimes seeds from those plants, possibly transported by ants, have grown into new plants in the front lawn. -

South Carolina Wildflowers by Color and Season

SOUTH CAROLINA WILDFLOWERS *Chokeberry (Aronia arbutifolia) Silky Camellia (Stewartia malacodendron) BY COLOR AND SEASON Mountain Camelia (Stewartia ovata) Dwarf Witch Alder (Fothergilla gardenii) Revised 10/2007 by Mike Creel *Wild Plums (Prunus angustifolia, americana) 155 Cannon Trail Road Flatwoods Plum (Prunus umbellata) Lexington, SC 29073 *Shadberry or Sarvis Tree (Amelanchier arborea, obovata) Phone: (803) 359-2717 E-mail: [email protected] Fringe Tree (Chionanthus virginicus) Yellowwood Tree (Cladratis kentuckeana) Silverbell Tree (Halesia carolina, etc.) IDENTIFY PLANTS BY COLOR, THEN Evergreen Cherry Laurel (Prunus caroliniana) SEASON . Common ones in bold print. Hawthorn (Crataegus viridis, marshalli, etc.) Storax (Styrax americana, grandifolia) Wild Crabapple (Malus angustifolia) WHITE Wild Cherry (Prunus serotina) SPRING WHITE Dec. 1 to May 15 SUMMER WHITE May 15 to Aug. 7 *Atamasco Lily (Zephyranthes atamasco) *Swamp Spiderlily (Hymenocallis crassifolia) Carolina Anemone (Anemone caroliniana) Rocky Shoals Spiderlily (Hymenocallis coronaria) Lance-leaved Anemone (Anemone lancifolia) Colic Root (Aletris farinosa) Meadow Anemone (Anemone canadensis) Fly-Poison (Amianthium muscaetoxicum) American Wood Anemone (Anemone quinquefolia) Angelica (Angelica venosa) Wild Indigo (Baptisia bracteata) Ground Nut Vine (Apios americana) Sandwort (Arenaria caroliniana) Indian Hemp (Apocynum cannabium) American Bugbane (Cimicifuga americana) Sand Milkweed (Asclepias humistrata) Cohosh Bugbane (Cimicifuga racemosa) White Milkweed (Asclepias -

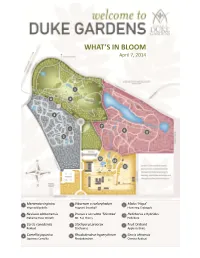

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

2009 Data Summary

USA‐NPN Technical Series 2010‐002 USA National Phenology Network 2009 Data Summary Theresa M. Crimmins1, Alyssa H. Rosemartin2, Kathryn A. Thomas3, R. Lee Marsh4, Ellen G. Denny5, Jake F. Weltzin6 1Partnerships & Outreach Coordinator, USA‐NPN National Coordinating Office; University of Arizona 2Information Technology & Communications Coordinator, USA‐NPN National Coordinating Office; University of Arizona 3Science Associate, USA‐NPN National Coordinating Office; US Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 4Applications Programmer, USA‐NPN National Coordinating Office; University of Arizona 5Monitoring Design & Data Coordinator, USA‐NPN National Coordinating Office; Northeast Regional Phenology Network 6Executive Director, USA‐NPN National Coordinating Office; US Geological Survey Suggested citation: Crimmins, T.M., A.H. Rosemartin, K.A. Thomas, R.L. Marsh, E.G. Denny, J.F. Weltzin. 2010. USA National Phenology Network 2009 Data Summary. USA‐NPN Technical Series 2010‐002. www.usanpn.org. USA National Phenology Network 2009 Data Summary 2 Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. USA National Phenology Network 2009 Data Summary 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................... -

Trumpet Vine Knowledge for the Community from Loudoun County Extension Master Gardeners Spring 2020

Trumpet Vine Knowledge for the Community From Loudoun County Extension Master Gardeners Spring 2020 Volume XVI, Issue 2 www.loudouncountymastergardeners.org LOUDOUN COUNTY We Can Depend on Spring EXTENSION MASTER GARDENER LECTURE SERIES In these uncertain times, there is great comfort in the FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC inevitability of spring. Trees are budding out and some 7 P.M. magnolias are beginning to bloom. (We won’t celebrate the RUST LIBRARY Bradford pears! Ugh!) Daffodils are in bloom, and the spring 380 OLD WATERFORD RD. NW wildflowers are emerging. Bloodroot is up and blooming on LEESBURG, VA 20176 sunny slopes, and the Virginia bluebells are beginning to emerge. IF INCLEMENT WEATHER CLOSES LOUDOUN COUNTY GOVERNMENT, It seems intuitive that with longer periods of sun and rising THE LECTURE WILL BE CANCELED. temperatures, plants are growing and blooming but what PLEASE CHECK THE CALENDAR ON THE triggers the plants is really just the opposite. FRONT PAGE OF OUR WEBSITE FOR THE LECTURE SERIES. CURRENTLY ALL In the fall, plants go dormant when the nights lengthen and then LIBRARY PROGRAMS ARE CANCELED. they start to sprout when the nights shorten. Also, some plants are able to measure the amount of cold that has occurred and when a sufficient number of chilling hours accumulates, they are triggered to bloom or send out new growth. Observe the spring wildflowers as they emerge. Some good sites are the Balls Bluff Regional Park in northeast Leesburg, River Bend Park in Great Falls, or just a local trail in a wooded area or along a stream. -

Liliaceae Lily Family

Liliaceae lily family While there is much compelling evidence available to divide this polyphyletic family into as many as 25 families, the older classification sensu Cronquist is retained here. Page | 1222 Many are familiar as garden ornamentals and food plants such as onion, garlic, tulip and lily. The flowers are showy and mostly regular, three-merous and with a superior ovary. Key to genera A. Leaves mostly basal. B B. Flowers orange; 8–11cm long. Hemerocallis bb. Flowers not orange, much smaller. C C. Flowers solitary. Erythronium cc. Flowers several to many. D D. Leaves linear, or, absent at flowering time. E E. Flowers in an umbel, terminal, numerous; leaves Allium absent. ee. Flowers in an open cluster, or dense raceme. F F. Leaves with white stripe on midrib; flowers Ornithogalum white, 2–8 on long peduncles. ff. Leaves green; flowers greenish, in dense Triantha racemes on very short peduncles. dd. Leaves oval to elliptic, present at flowering. G G. Flowers in an umbel, 3–6, yellow. Clintonia gg. Flowers in a one-sided raceme, white. Convallaria aa. Leaves mostly cauline. H H. Leaves in one or more whorls. I I. Leaves in numerous whorls; flowers >4cm in diameter. Lilium ii. Leaves in 1–2 whorls; flowers much smaller. J J. Leaves 3 in a single whorl; flowers white or purple. Trillium jj. Leaves in 2 whorls, or 5–9 leaves; flowers yellow, small. Medeola hh. Leaves alternate. K K. Flowers numerous in a terminal inflorescence. L L. Plants delicate, glabrous; leaves 1–2 petiolate. Maianthemum ll. Plant coarse, robust; stems pubescent; leaves many, clasping Veratrum stem. -

Plant Phenophase Datasheet Contact: [email protected] | More Information

Species: Clintonia borealis Forbs Common Name: bluebead Directions: Fill in the date and time in the top rows and circle the appropriate letter in the column below. Nickname: y (phenophase is occurring); n (phenophase is not occurring); ? (not certain if the phenophase is occurring). Site: Do not circle anything if you did not check for the phenophase. In the adjacent blank, write in the appropriate measure of intensity or abundance for this phenophase. Year: Observer: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Do you see... Time: Time: Time: Time: Time: Time: Time: Time: Initial growth Leaves Flowers or flower buds Open flowers Fruits Ripe fruits Recent fruit or seed drop Check when data entered online: Comments: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Do you see... Time: Time: Time: Time: Time: Time: Time: Time: Initial growth Leaves Flowers or flower buds Open flowers Fruits Ripe fruits Recent fruit or seed drop Check when data entered online: Comments: Plant Phenophase Datasheet Contact: [email protected] | More information: www.usanpn.org/how-observe PAPERWORK REDUCTION ACT STATEMENT: In accordance with the Paperwork Reduction Act (44 U.S.C. 3501), please note the following. This information collection is authorized by Organic Act, 43 U.S.C. 31 et seq., 1879 and Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act. Your response is voluntary. We estimate that it will take approximately 2 minutes to make and report observations per respo- ndent. An agency may not conduct or sponsor and a person is not required to respond to a collection of information unless it displays a currently valid Office of Management and Budget control number. -

Plant and Wildlife List, Geology Summary, Resources

ROCK CREEK PARK PLANT & WILDLIFE LIST PEIRCE MILL AREA Smithsonian Associates Nature/History Hike & Virtual Presentation with Melanie Choukas-Bradley, Author of A Year in Rock Creek Park, City of Trees, Finding Solace at Theodore Roosevelt Island & forest bathing books July 2021 Woody Plants (*Non-Natives) Trees unless identified as Shrub or Vine Acer negundo Box-Elder or Ash-Leaved Maple Acer platanoides Norway Maple* Acer rubrum Red Maple Acer saccharum Sugar Maple Acer saccharinum Silver Maple Ailanthus altissima Ailanthus or Tree of Heaven* Albizia julibrissin Mimosa or Silk-Tree* Amelanchier Shadbush or Serviceberry Asimina triloba Pawpaw Betula nigra River Birch Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam, Ironwood or Musclewood Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory Carya glabra Pignut Hickory Carya illinoinensis Pecan (planted) Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory (planted) Carya laciniosa Shellbark Hickory (planted) Carya tomentosa Mockernut Hickory (C. alba) Catalpa speciosa Northern Catalpa (native to the midwest; naturalized) Cercis canadensis Redbud Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Diospyros virginiana Persimmon Euonymus alatus Winged Euonymus or Burning Bush* (shrub) Euonymus americanus Strawberry Bush (shrub) Fagus grandifolia American Beech Fraxinus americana White Ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash Hamamelis virginiana Witch-Hazel (shrub or small tree with yellow late- autumn flowers) Hydrangea arborescens Hydrangea, Wild (shrub) Ilex opaca American Holly Juglans nigra Black Walnut Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red-Cedar, Virginia Juniper 2 | P a g e Kalmia latifolia Mountain Laurel (evergreen shrub) Lindera benzoin Spicebush (shrub) Liquidambar styraciflua Sweetgum (planted near Peirce Mill & Milkhouse Ford) Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip-Tree (Tulip Poplar) Lonicera maackii Maack’s Honeysuckle* (shrub) Magnolia grandiflora Southern Magnolia (planted) Magnolia macrophylla Bigleaf Magnolia (naturalized from the south) Magnolia tripetala Umbrella Magnolia Malus spp.