Part in Operations Where the EU Does Not Use NATO Assets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Historical Study of the Development of a European Army Written by Snezhana Stadnik

A Comparative Historical Study of the Development of a European Army Written by Snezhana Stadnik This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. A Comparative Historical Study of the Development of a European Army https://www.e-ir.info/2016/05/12/a-comparative-historical-study-of-the-development-of-a-european-army/ SNEZHANA STADNIK, MAY 12 2016 Has the Time Come? – A Comparative Historical Study of the Obstacles Facing the Development of a European Army Almost 70 years ago, a polity was created which instituted a legacy of peace among incessantly warring states. This remarkable feat, a collection of nation-states called the European Union (EU), has been the object of much research and observation. Starting off as an economic community, then growing into a new kind of federalist suprastate, 28 countries today have come together to participate in the blurring of national borders, achieving more success in market integration than foreign and security policy. This hybrid system of supranationalism and intergovernmentalism is incrementally evolving as decision-makers create and refine institutions and mechanisms to respond to needs, ultimately moving the Union forward. One such decision-maker, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, recently re-surfaced an important issue: the need for a European army.[1] This has not been the first time that an influential European official has called for such a development. Every decade, the issue is revisited, with German Chancellor Angel Merkel recently wishing for a European army on her birthday.[2] Despite many developments in defense and security policy in the last several decades, one thing remains certain: the same underlying reasons that historically precluded the development of a supranational European army remain relevant today. -

The Evolution of Intergovernmental Cooperation in the European Process

1 Article à paraître en janvier dans Challenge Europe, le magazine on-line du European Policy Center The Evolution of Intergovernmental Cooperation in the European process. The Luxemburg report, also known as the Davignon report, adopted by Foreign Ministers in October 1970 is a generally accepted departure point for intergovernmental cooperation among members of the European Community. It was the first time that the “Community method”, devised by Jean Monnet and consolidated by the treaty of Rome on the basis of texts prepared by the Spaak Committee, was deliberately discarded, in the field of foreign policy, in favour of the traditional methods of diplomatic consultation, in an exercise initially known as “political cooperation”. The significance of that initial step can only be understood by a flashback to the failure of the Fouchet negotiations in the spring of 1962. That negotiation, launched and largely dominated by General de Gaulle, had been understood by his partners as a deliberate attempt to subordinate the nascent European Community to an intergovernmental construction established in Paris, presumably dominated by France, and without any of the supranational procedures or institutions which had made Monnet’s proposals acceptable to the smaller countries. Its final failure was immediately perceived as a turning point, as a clear parting of the ways between the Gaullist concept of l’Europe des patries and the supranational concept developed in the fifties. It was moreover quite acrimonious: participants accusing each other of arrogant and irresponsible behaviour. In his memoirs Paul-Henri Spaak, who played a prominent role both as Belgian Foreign Minister and as foster father of the treaty of Rome, clearly puts the responsibility on the shoulders of Couve de Murville. -

CODE of CONDUCT “ Our Reputation, Our Brand, and the Trust of Our Stakeholders Are Irreplaceable Assets We All Must Protect.”

CODE OF CONDUCT “ Our reputation, our brand, and the trust of our stakeholders are irreplaceable assets we all must protect.” Dear Colleagues, An important part of our job is to read and understand the Code and be familiar with Thank you for taking the time to review our Code resources for our questions or concerns. While our of Conduct. Code may not answer every question, it contains guidance and information about how to learn I am proud to lead this Company, knowing that we more. Speaking up is the Western Union way. I better the lives of our customers around the world encourage anyone with questions or concerns to every day. We operate in more than 200 countries speak up. and territories and our customers rely on us to help them succeed. The key to our growth is working together with integrity and succeeding in the right way. Western Union has a rich and diverse history. We I appreciate all you do to promote our shared have thrived for more than 167 years because values and adhere to our Code. Our Code is the of our determination to meet the needs of our cornerstone of our success. customers and evolve our way of working. Sincerely, Each of us has a responsibility to act ethically and with integrity. We all have a role in making sure our business is conducted in the right way and that we comply with our policies, our Code of Conduct, and the law. Our Code is the foundation for how we work, a statement of our principles, Hikmet Ersek and a guide for navigating issues and getting help. -

Training and Simulation

Food for thought 05-2021 Training and Simulation Written by AN EXPERTISE FORUM CONTRIBUTING TO EUROPEAN CONTRIBUTING TO FORUM AN EXPERTISE SINCE 1953 ARMIES INTEROPERABILITY the Research team of Finabel European Army Interoperability Center This study was written under the guidance of the Swedish presidency, headed by MG Engelbrektson, Commander of the Swedish Army. Special thanks go out to all ex- perts providing their insights on the topic, including but not limited too: MAJ Ulrik Hansson-Mild, Mr Henrik Reimer, SSG Joel Gustafsson, Mr Per Hagman, Robert Wilsson, MAJ Björn Lahger and SGM Anders Jakobsson.This study was drawn up by the Research team of Finabel over the course of a few months, including: Cholpon Abdyraeva, Paolo d'Alesio, Florinda Artese, Yasmine Benchekroun, Antoine Decq, Luca Dilda, Enzo Falsanisi, Vlad Melnic, Oliver Noyan, Milan Storms, Nadine Azi- hane, Dermot Nolan under the guidance of Mr Mario Blokken, Director of the Per- manent Secretariat. This Food for Thought paper is a document that gives an initial reflection on the theme. The content is not reflecting the positions of the member states but consists of elements that can initiate and feed the discussions and analyses in the domain of the theme. All our studies are available on www.finabel.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Data Utilisation, the Need for Standardisation and Obstacles 33 Cultural Interoperability 4 Introduction 33 Introduction 4 9. What is Data? 34 1. Exercises as Means to 10. Political Aspects: National Deter Opposition 5 Interests vs. Interoperability 34 2. Current Trends in SBT 13 11. Data Interoperability 3. -

The Historical Development of European Integration

FACT SHEETS ON THE EUROPEAN UNION The historical development of European integration PE 618.969 1. The First Treaties.....................................................................................................3 2. Developments up to the Single European Act.........................................................6 3. The Maastricht and Amsterdam Treaties...............................................................10 4. The Treaty of Nice and the Convention on the Future of Europe..........................14 5. The Treaty of Lisbon..............................................................................................18 EN - 18/06/2018 ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This leaflet contains a compilation of Fact Sheets provided by Parliament’s Policy Departments and Economic Governance Support Unit on the relevant policy area. The Fact Sheets are updated regularly and published on the website of the European Parliament: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets ABOUT THE PUBLISHER Author of the publication: European Parliament Department responsible: Unit for Coordination of Editorial and Communication Activities E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript completed in June, 2018 © European Union, 2018 DISCLAIMER The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice -

The Evolution of a Common EU Foreign, Security and Defence Policy

Chronology: The Evolution of a Common EU Foreign, Security and Defence Policy March 1948: Belgium, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the UK sign the Brussels Treaty of mutual defence. April 1949: The US, Canada and ten West European countries sign the North Atlantic Treaty . May 1952: The European Defence Community treaty is agreed by the six ECSC member states. It would have created a common European army, and permitted West Germany’s rearmament. In August 1954, the French National Assembly rejects the treaty. October 1954: The Western European Union (WEU) is created on the basis of the Brussels Treaty, and expanded to include Italy and West Germany. West Germany joins NATO. December 1969: At their summit in The Hague , the EC heads of state or government ask the foreign ministers to study ways to achieve progress in political unification. October 1970: The foreign ministers approve the Luxembourg Report , setting up European Political Cooperation. They will meet every six months, to coordinate their positions on international problems and agree common actions. They will be aided by a committee of the directors of political affairs (the Political Committee ). July 1973: The foreign ministers agree to improve EPC procedures in the Copenhagen Report . They will meet at least four times a year; the Political Committee can meet as often as necessary. European Correspondents and working groups will help prepare the Political Committee’s work. The Commission can contribute its views to proceedings. October 1981: Measures approved in the London Report include the crisis consultation mechanism: any three foreign ministers can convene an emergency EPC meeting within 48 hours. -

International Military Staff, Is to Provide the Best Possible C3 Staff Executive Operations, Strategic Military Advice and Staff Support for the Military Committee

Director General of IMS Public Affairs & Financial Controller StratCom Executive Coordinator Advisor Legal Office HR Office NATO Office Support Activities on Gender Perspectives SITCEN Cooperation NATO Intelligence Operations Plans & Policy & Regional Logistics Headquarters Security & Resources C3 Staff Intelligence Major Operation Strategic Policy Partnership Concepts Logistics Branch Executive Production Branch Alpha & Concepts & Policy Branch Coordination Office Branch Intelligence Policy Joint Operations Nuclear Special Partnerships Medical Branch Information Services Branch & Plans Branch & CBRN Defence Branch Branch Education Training Defence and Regional Partnerships Plans, Policy & Exercise & Evaluation Force Planning Armaments Branch Branch Branch Architecture Branch Air & Missile Infrastructure & Spectrum & C3 Defence Branch Finance Branch Infrastructure Branch Operations, Manpower Branch Requirements, & Plans Branch NATO Defence Information Assurance Consists of military/civilian staff from member nations. Manpower & Cyber Defence Personnel work in international capacity for the common interest of the Alliance. Audit Authority Branch www.nato.int/ims e-mail :[email protected] Brussels–Belgium 1110 HQ, NATO Office,InternationalMilitaryStaff, Affairs the Public For moreinformationcontact: NATO HQ. NATO and the moveto thenew NATO are adaptedtoreflect Future ‘ways ofworking’ changes are not it likely, will be important that the IMS is reconfigured and its a review of the IMS Summit, Chicago the was at direction initiated. Government and State While of Heads major the Following structural and organizational respected andthatistotallyfreefromdiscriminationprejudice. is individual each which in environment an in communication open and initiative resilience, for need the and learning continuous promote also They commitment. first, Mission always.’ Our peopleThe workIMS with professionalism,team integrityembraces and the principles and values enshrined Values in ‘People decisiveness andpride. -

NATO 20/2020: Twenty Bold Ideas to Reimagine the Alliance After The

NATO 2O / 2O2O TWENTY BOLD IDEAS TO REIMAGINE THE ALLIANCE AFTER THE 2020 US ELECTION NATO 2O/2O2O The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. The Scowcroft Center’s Transatlantic Security Initiative brings together top policymakers, government and military officials, business leaders, and experts from Europe and North America to share insights, strengthen cooperation, and develop innovative approaches to the key challenges facing NATO and the transatlantic community. This publication was produced in partnership with NATO’s Public Diplomacy Division under the auspices of a project focused on revitalizing public support for the Alliance. NATO 2O / 2O2O TWENTY BOLD IDEAS TO REIMAGINE THE ALLIANCE AFTER THE 2020 US ELECTION Editor-in-Chief Christopher Skaluba Project and Editorial Director Conor Rodihan Research and Editorial Support Gabriela R. A. Doyle NATO 2O/2O2O Table of Contents 02 Foreword 56 Design a Digital Marshall Plan by Christopher Skaluba by The Hon. Ruben Gallego and The Hon. Vicky Hartzler 03 Modernize the Kit and the Message by H.E. Dame Karen Pierce DCMG 60 Build Resilience for an Era of Shocks 08 Build an Atlantic Pacific by Jim Townsend and Anca Agachi Partnership by James Hildebrand, Harry W.S. Lee, 66 Ramp Up on Russia Fumika Mizuno, Miyeon Oh, and by Amb. -

Basic Documents Page 1 of 2

EUROCORPS - Basic Documents Page 1 of 2 08/30/2005 - 03:06 pm Home Organisation Missions History Press Gallery Links Contact About us Basic Documents Basic Documents This page contains brief descriptions of the basic documents that are considered of major importance for Principles of understanding Eurocorps' birth, composition and/or use. Employment Possible missions SFOR 1998 KFOR 2000 News Press releases Eurogazette ISAF VI La Rochelle Report: The "La Rochelle Report" is the founding act of the Eurocorps. This document defines the Eurocorps as a European multinational army corps that does not belong to the integrated military structure of the North Atlantic Alliance (NATO). It further describes more precisely the missions, subordination, employment possibilities, structure, and organisation of the Eurocorps, as well as a number of financial and legal aspects. Initially a French-German initiative, the Eurocorps was declared open for membership by other WEU-countries. The Petersberg and Rome Declarations: The Petersberg Declaration, made on the occasion of a Western European Union Summit on June 19, 1992, defined the WEU's role as the defence part of the European Union (cp. Maastricht Treaty, Amsterdam Treaty) and as an instrument to strengthen the Atlantic Alliance's European pillar. In support of this decision, the Corps member states decided on May 19, 1993 in Rome, to put the Eurocorps at the WEU's disposal. Three types of employment are envisaged: { the Eurocorps is to be prepared to carry out humanitarian aid missions and population -

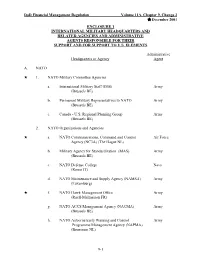

Dod Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9

DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9, Change 2 December 2001 ENCLOSURE 1 INTERNATIONAL MILITARY HEADQUARTERS AND RELATED AGENCIES AND ADMINISTRATIVE AGENTS RESPONSIBLE FOR THEIR SUPPORT AND FOR SUPPORT TO U.S. ELEMENTS Administrative Headquarters or Agency Agent A. NATO 1. NATO Military Committee Agencies a. International Military Staff (IMS) Army (Brussels BE) b. Permanent Military Representatives to NATO Army (Brussels BE) c. Canada - U.S. Regional Planning Group Army (Brussels BE) 2. NATO Organizations and Agencies a. NATO Communications, Command and Control Air Force Agency (NC3A) (The Hague NL) b. Military Agency for Standardization (MAS) Army (Brussels BE) c. NATO Defense College Navy (Rome IT) d. NATO Maintenance and Supply Agency (NAMSA) Army (Luxemburg) f. NATO Hawk Management Office Army (Ruell-Malmaison FR) g. NATO ACCS Management Agency (NACMA) Army (Brussels BE) h. NATO Airborne Early Warning and Control Army Programme Management Agency (NAPMA) (Brunssum NL) 9-1 DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 11A, Chapter 9, Change 2 December 2001 Administrative Headquarters or Agency Agent i. NATO Airborne Early Warning Force Command Army (Mons BE) j. NATO Airborne Early Warning Main Operating Base Air Force (Geilenkirchen GE) k. NATO CE-3A Component Air Force (Geilenkirchen GE) l. NATO Research and Technology Organization (RTO) Air Force (Nueilly-sur-Seine FR) l. NATO School Army (Oberammergau GE) m. NATO CIS Operating and Support Agency (NACOSA) Army (Glons BE) n. NATO Communication and Information Systems School Navy (NCISS) (Latina, IT) o. NATO Pipeline Committee (NPC) Army (Glons BE) p. NATO Regional Operating Center Atlantic Navy (ROCLANT)/NACOSA Support Element (NSE) West (Oeiras PO) 3. -

Death of an Institution: the End for Western European Union, a Future

DEATH OF AN INSTITUTION The end for Western European Union, a future for European defence? EGMONT PAPER 46 DEATH OF AN INSTITUTION The end for Western European Union, a future for European defence? ALYSON JK BAILES AND GRAHAM MESSERVY-WHITING May 2011 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1785 7 D/2011/4804/136 U 1612 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. -

Qualified Majority Voting from the Single European Act to Present Day: an Unexpected Permanence

Qualified majority voting from the Single European Act to present day: an unexpected permanence Stéphanie NOVAK Studies & 88 Research Study & Qualified majority voting from the Single European Act 88 to the present day: Research an unexpected permanence Stéphanie novak Stéphanie Novak Stéphanie Novak is a research fellow at the Hertie School of Governance (Berlin). She previously held research positions at the European University Institute (Florence), Collège de France (Paris) and Harvard University. She holds a Ph.D. in political science (Institut d’études politiques de Paris, 2009) and is an alumna of the École normale supérieure (ENS). She graduated in philosophy (Master and agregation). Her Ph.D. thesis was published in 2011 by Dalloz, Paris: La prise de décision au Conseil de l’Union européenne. Pratiques du vote et du consensus. Qualified majority voting from the Single european act to the preSent day: an unexpected permanence Notre Europe Notre Europe is an independent think tank devoted to European integration. Under the guidance of Jacques Delors, who created Notre Europe in 1996, the association aims to “think a united Europe”. Our ambition is to contribute to the current public debate by producing analyses and pertinent policy proposals that strive for a closer union of the peoples of Europe. We are equally devoted to promoting the active engagement of citizens and civil society in the process of community construction and the creation of a European public space. In this vein, the staff of Notre Europe directs research projects; produces and disseminates analyses in the form of short notes, studies, and articles; and organises public debates and seminars.