The Essence of Porsche the 908/03 Distils All of the Zuffenhausen Factory’S Cornering Expertise in a Single Racing Car

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Porsche in Le Mans

Press Information Meet the Heroes of Le Mans Mission 2014. Our Return. Porsche at Le Mans Meet the Heroes of Le Mans • Porsche and the 24 Hours of Le Mans 1 Porsche and the 24 Hours of Le Mans Porsche in the starting line-up for 63 years The 24 Hours of Le Mans is the most famous endurance race in the world. The post-war story of the 24 Heures du Mans begins in the year 1949. And already in 1951 – the pro - duction of the first sports cars in Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen commenced in March the previous year – a small delegation from Porsche KG tackles the high-speed circuit 200 kilometres west of Paris in the Sarthe department. Class victory right at the outset for the 356 SL Aluminium Coupé marks the beginning of one of the most illustrious legends in motor racing: Porsche and Le Mans. Race cars from Porsche have contested Le Mans every year since 1951. The reward for this incredible stamina (Porsche is the only marque to have competed for 63 years without a break) is a raft of records, including 16 overall wins and 102 class victories to 2013. The sporting competition and success at the top echelon of racing in one of the world’s most famous arenas is as much a part of Porsche as the number combination 911. After a number of class wins in the early fifties with the 550, the first time on the podium in the overall classification came in 1958 with the 718 RSK clinching third place. -

GT 40 Reunion

,9O Accord: tlotsred viclor BORN IO SUCCEEDA]IID Sfltt DRIITEN AT 25 Many of the Ford GT40s thnt won fame and glory at LeMans gather for a siluer anniuersary reunion marhed most fittingly - by racing By Cynthia Claes ime allows us to modify our 30 years ago, have helped keep the cars memories, to enhance the past, on the racetrack. to make events fit our recollec- "The SVRA believes that past Ecing tioos. Even so, maybe it was history should not be a static display in a the Septembq sun that put a museum," said Quattlebaum. "Our goal glow on our remembrances. After all, is to encouage the restomtion, preserva- Watkins Glen is not a place noted for tion and use of historically significant race abu[dant sunshine. Especially in autumn. cars. ' Quanlebaum s emphasis is on lrJe. Watkins in the fall is a place where you And SVRA'S president sets a good ex- can feel the wind lising, and where the ample. He recently retumed from Europe, rain falls hard and cold. And often. where he competed in vintage races-at But this was a silver anniversary. And Spa and Nurburgring-his Devin SS a The Glen rewarded us with sunshine, surprise winner at the Belgian event and Stirling Moss and old Fords. Very spe- on hand to compete again this weekend. cial old Fords. The GT40 was a quarter "The Europeans are very serious about of a century young. vintage racing," he said. "All manner of To celebrate, the Sports Car Vintage cars tum up. Imagine five 250 Maseralis Racing Association (SVRA) organized a rounding the La Source hairpin at Spa. -

In Safe Hands How the Fia Is Enlisting Support for Road Safety at the Highest Levels

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA: Q1 2016 ISSUE #14 HEAD FIRST RACING TO EXTREMES How racing driver head From icy wastes to baking protection could be deserts, AUTO examines how revolutionised thanks to motor sport conquers all pioneering FIA research P22 climates and conditions P54 THE HARD WAY WINNING WAYS Double FIA World Touring Car Formula One legend Sir Jackie champion José Maria Lopez on Stewart reveals his secrets for his long road to glory and the continued success on and off challenges ahead P36 the race track P66 P32 IN SAFE HANDS HOW THE FIA IS ENLISTING SUPPORT FOR ROAD SAFETY AT THE HIGHEST LEVELS ISSUE #14 THE FIA The Fédération Internationale ALLIED FOR SAFETY de l’Automobile is the governing body of world motor sport and the federation of the world’s One of the keys to bringing the fight leading motoring organisations. Founded in 1904, it brings for road safety to global attention is INTERNATIONAL together 236 national motoring JOURNAL OF THE FIA and sporting organisations from enlisting support at the highest levels. over 135 countries, representing Editorial Board: millions of motorists worldwide. In this regard, I recently had the opportunity In motor sport, it administers JEAN TODT, OLIVIER FISCH the rules and regulations for all to engage with some of the world’s most GERARD SAILLANT, international four-wheel sport, influential decision-makers, making them SAUL BILLINGSLEY including the FIA Formula One Editor-in-chief: LUCA COLAJANNI World Championship and FIA aware of the pressing need to tackle the World Rally Championship. Executive Editor: MARC CUTLER global road safety pandemic. -

The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN by Michael Browning

The Formula 1 Porsche displayed an interesting disc brake design and pioneering cooling fan placed horizontally above its air-cooled boxer engine. Dan Gurney won the 1962 GP of France and the Solitude Race. Thereafter the firm withdrew from Grand Prix racing. The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN By Michael Browning Rouen, France July 8th 1962: It might have been a German car with an American driver, but the big French crowd But that was not the end of Porsche’s 1969 was on its feet applauding as the sleek race glory, for by the end of the year the silver Porsche with Dan Gurney driving 908 had brought the marque its first World took the chequered flag, giving the famous Championship of Makes, with notable wins sports car maker’s new naturally-aspirated at Brands Hatch, the Nurburgring and eight cylinder 1.5 litre F1 car its first Grand Watkins Glen. Prix win in only its fourth start. The Type 550 Spyder, first shown to the public in 1953 with a flat, tubular frame and four-cylinder, four- camshaft engine, opened the era of thoroughbred sports cars at Porsche. In the hands of enthusiastic factory and private sports car drivers and with ongoing development, the 550 Spyder continued to offer competitive advantage until 1957. With this vehicle Hans Hermann won the 1500 cc category of the 3388 km-long Race “Carrera Panamericana” in Mexico 1954. And it was hardly a hollow victory, with The following year, Porsche did it all again, the Porsche a lap clear of such luminaries this time finishing 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th in as Tony Maggs’ and Jim Clark’s Lotuses, the Targa Florio with its evolutionary 908/03 Graham Hill’s BRM. -

Le Mans (Not Just) for Dummies the Club Arnage Guide

Le Mans (not just) for Dummies The Club Arnage Guide to the 24 hours of Le Mans 2011 "I couldn't sleep very well last night. Some noisy buggers going around in automobiles kept me awake." Ken Miles, 1918 - 1966 Copyright The entire contents of this publication and, in particular of all photographs, maps and articles contained therein, are protected by the laws in force relating to intellectual property. All rights which have not been expressly granted remain the property of Club Arnage. The reproduction, depiction, publication, distr bution or copying of all or any part of this publication, or the modification of all or any part of it, in any form whatsoever is strictly forbidden without the prior written consent of Club Arnage (CA). Club Arnage (CA) hereby grants you the right to read and to download and to print copies of this document or part of it solely for your own personal use. Disclaimer Although care has been taken in preparing the information supplied in this publication, the authors do not and cannot guarantee the accuracy of it. The authors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions and accept no liability whatsoever for any loss or damage howsoever arising. All images and logos used are the property of Club Arnage (CA) or CA forum members or are believed to be in the public domain. This guide is not an official publication, it is not authorized, approved or endorsed by the race-organizer: Automobile Club de L’Ouest (A.C.O.) Mentions légales Le contenu de ce document et notamment les photos, plans, et descriptif, sont protégés par les lois en vigueur sur la propriété intellectuelle. -

90Th Anniversary of the Targa Florio Victory: Bugatti Wins Fifth Consecutive Title

90th anniversary of the Targa Florio victory: Bugatti wins fifth consecutive title MOLSHEIM 02 05 2019 FOR MANY YEARS BUGATTI DOMINATED THE MOST IMPORTANT CAR RACE OF THE 1920S Legends were born on this track. Targa Florio in Sicily was considered the world’s hardest, most prestigious and most dangerous long-distance race for many years. Today, current Bugatti models remind us of the drivers from back in the day. Sicilian entrepreneur Vincenzo Florio established his own race on family-owned roads in the Madonie region. Between 1906 and 1977, sports cars raced for the title at international races, some of which even had sports car world championship status. Winners at this race could proudly advertise their victory. For this reason, all important sports car manufacturers sent their vehicles to Sicily. Between 1925 and 1929 Bugatti dominated the race with the Type 35. In particular, in 1928 and 1929, one man showcased his skills at the wheel of his vehicle: Albert Divo. In these two years he was unbeatable in his Bugatti Type 35 C, winning the race in Sicily on 5 May 1929 after having also claimed the top spot in 1928. He also set a further record when he crossed the finish line: the “Fabrik Bugatti” team won the title five times in a row – this had never been done before in the history of the Targa Florio and remained an unbeaten record until the end of the last official races, to this day. A reason to look back. After all, the race was anything but easy: initially one lap of the “Piccolo circuito delle Madonie” was around 148 kilometres, from 1919 organisers cut the race lap distance to a still considerable 108 kilometres. -

Fiskens Stocklist Spring 2020

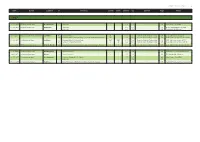

Where the world’s greatest cars come to be sold STOCK LIST SPRING 2020 1931 BENTLEY 4½ LITRE BLOWER #XT3631 Desirable late crank model now fitted with Amherst Villiers Supercharger n Recently raced at Goodwood Revival 2019 in the Brooklands Trophy 1967 FORD GT40 #GT40 P/1069 Supplied to Shelby America and sent by John Wyer to Garage Filippinetti for the 1967 Geneva Motor Show n Part of the Ford press fleet then sold to Sir Anthony Bamford of JCB excavator fame n Later featured in the Motor magazine, GT40P/ 1069 turned a ¼ mile in 12.4 seconds and 0-100 MPH in 9.1 seconds n Recently prepared and rebuilt for historic racing by Gelscoe Motorsport 1954 MASERATI A6GCS/53 #2071 Ex-Jean Estager, Tour de France class winner n Modified in period to long-nose with headrest n Comprehensive history and still complete with the original engine n One of the most recognised and loved participants on the Mille Miglia, initially in the 1980’s in the hands of Stirling Moss and 15 times with its current owners family 1931 BENTLEY 4½ LITRE #XT3627 One of the last 4½ Bentleys produced n Built new to “heavy crank” specification n Matching engine and chassis n Rare Maythorns of Biggleswade Sportsmans Coupé Coachwork n In single ownership for over 60 years n Accompanied by a Clare Hay report 1948 LAGO TALBOT T26C #110002 The second of Anthony Lago’s legendary 4½ litre monopostos n Competed extensively in European Grand Prix driven by Raph, Chaboud, Mairesse, Chiron and Étancelin n Exported to Australia in 1955 with continued racing success in the hands of Doug -

The Bahn Stormer Volume XXIII, Issue I -- January,-February 2018

The Bahn Stormer Volume XXIII, Issue I -- January,-February 2018 Photo by Stewart Free Don’t dispair -- clear roads will return!!! Photo by Jeremy Goddard The Official Publication of the Rally Sport Region - Porsche Club of America The Bahn Stormer Contents For Information or submissions Contact Mike O’Rear The Official Page ......................................................3 [email protected] On the Grid.......................................... ....................5 (Please put Bahn Stormer in the subject line) Membership Page ....................................................6 Deadline: Normally by the end of the third Calendar of Events........................................... ........7 week-end of the month. Holiday Party ............................................................8 Points, Condensers & Such ....................................10 Material from the The Bahn Stormer may be reprinted Partners/Spouses & Car Guys ................................13 (except for ads) provided proper credit is given to the Ramblings From a Life With Cars ...........................15 author and the source. One Man’s Bucket (Seat) List..................................17 Crossy Kids .............................................................18 For Commercial Ads Contact Rick Mammel Around the Zone ....................................................21 [email protected] Tale of a Tail ...........................................................22 Classifieds ..............................................................24 Advertising -

750 Motor Club North Herts Centre

750 Motor Club, North Herts Centre Hugh Dibley’s Life as Racing Driver & Constructor Work in Aircraft Fuel Conservation & Noise Reduction – started into London Heathrow in 1975 Racing Driver 1959 - 1974 Racing Car Constructor 1967-72 (Palliser Racing Design Limited) 1979 Awarded Guild of Air Pilots Brackley Memorial Trophy For work on Fuel Conversation started in 1973 Hugh Dibley - Motor Racing as Driver & Constructor & Aircraft Fuel Conservation /Noise Reduction 6 Nov 2013 1/96 Hugh Dibley’s talk to 750 Motor Club, North Herts Centre Racing Driver – privateer and semi-professional – Howmet TX Gas Turbine sports racer 1967-1972 Palliser Racing Design Limited Development of a new model by a small constructor Practical effects of aerodynamics Reason for end racing as racing driver Work on aircraft Fuel Conservation and Approach Noise Reduction and to Improve Safety on Non Precision Approaches – where unnecessary accidents still happen. Video of First BOAC 500 Sports Car Race, Brands Hatch, 1967 Hugh Dibley - Motor Racing as Driver & Constructor & Aircraft Fuel Conservation /Noise Reduction 6 Nov 2013 2/96 HPK Dibley’s Motor Racing Background 1959–1962 Raced own cars and mainly did own maintenance 1959-60 AC Aceca Bristol 1960 Lola Formula Junior 1961 Lola Formula Junior & 1st Lola Formula 1! 1962 Lola Formula Junior 1964–1965 Raced own cars under Stirling Moss Automobile Racing Team 1967 Raced own Camaro 1964 Brabham BT8 2.5 litre Climax Sports Racing Car 1965 Lola T70 Chevrolet 6 litre / 489 bhp 1967 Chevrolet Camaro Modified Saloon Possible -

ACES WILD ACES WILD the Story of the British Grand Prix the STORY of the Peter Miller

ACES WILD ACES WILD The Story of the British Grand Prix THE STORY OF THE Peter Miller Motor racing is one of the most 10. 3. BRITISH GRAND PRIX exacting and dangerous sports in the world today. And Grand Prix racing for Formula 1 single-seater cars is the RIX GREATS toughest of them all. The ultimate ambition of every racing driver since 1950, when the com petition was first introduced, has been to be crowned as 'World Cham pion'. In this, his fourth book, author Peter Miller looks into the back ground of just one of the annual qualifying rounds-the British Grand Prix-which go to make up the elusive title. Although by no means the oldest motor race on the English sporting calendar, the British Grand Prix has become recognised as an epic and invariably dramatic event, since its inception at Silverstone, Northants, on October 2nd, 1948. Since gaining World Championship status in May, 1950 — it was in fact the very first event in the Drivers' Championships of the W orld-this race has captured the interest not only of racing enthusiasts, LOONS but also of the man in the street. It has been said that the supreme test of the courage, skill and virtuosity of a Grand Prix driver is to w in the Monaco Grand Prix through the narrow streets of Monte Carlo and the German Grand Prix at the notorious Nürburgring. Both of these gruelling circuits cer tainly stretch a driver's reflexes to the limit and the winner of these classic events is assured of his rightful place in racing history. -

Conversations with Peter Gregg

www.porscheroadandrace.com Conversations with Peter Gregg Published: 21st April 2017 By: Martin Raffauf Online version: https://www.porscheroadandrace.com/conversations-with-peter-gregg/ Peter Gregg and Hurley Haywood won the 24 Hours of Daytona on 3/4 February 1973 driving this 911 Carrera RSR 2.8 Peter Gregg was the IMSA driver every one strived to beat. He started in the early ‘70s with Porsches and had done very well. He won the first championship in 1971, sharing a Porsche with Hurley Haywood in the GTU class (under 2.5-litre). By 1973 he was running the iconic Porsche Carrera RSR and he would win the IMSA title in 1973, 1974 and 1975. By then he was known as ‘Peter Perfect,’ always approaching his racing in a very professional way, trying to leave nothing to chance. In 1976, on one occasion IMSA would not allow the 934 to run, and he realised that the RSR would struggle, and so switched to the factory BMW CSL. www.porscheroadandrace.com He was beaten to the title by Al Holbert in a Chevrolet Monza. By 1977 IMSA had decided to allow a 934 ½ to run, but this was no ordinary 934, this was a specially made 934 with some permitted changes, sort of like a 934 on steroids. Peter Gregg and Guy Chasseuil finished in 14th place overall and third in the Grand Touring 3000 class in the 1973 Le Mans in the #48 911 Carrera RSR Peter Gregg showed up with one of these at Sebring and promptly sold the car to Jim Busby, as he had a second new one on the way. -

Unknown - - 001 2.0 - LH Lang Heck | Long Tail

Copyright © Rob Semmeling 1 Date Event Location # Driver(s) Overall Class Chassis CC Entrant Type Notes 1967 00.04.1967 Porsche private test Hockenheim - Unknown - - 001 2.0 - LH Lang Heck | Long Tail 00.04.1967 Porsche private test Unknown - Unknown - - 001 2.0 - LH At the Volkswagen test track - Unknown - - 002 2.0 - LH Possibly in Wolfsburg ? 09.04.1967 Essais des 24 Heures du Mans Le Mans 40 Gerhard Mitter 21 - 001 2.0 Porsche System Engineering LH S-ZL 126 | later scrapped 41 Gerhard Mitter | Herbert Linge | Fritz Huschke von Hanstein 28 - 002 2.0 Porsche System Engineering LH S-ZD 946 | scrapped in Dec 1967 11.06.1967 24 Heures du Mans Le Mans 40 Gerhard Mitter | Jochen Rindt DNF DNF 003 2.0 Porsche System Engineering LH S-ZL 691 | red nose | QF 22 41 Jo Siffert | Hans Herrmann 5 1 004 2.0 Porsche System Engineering LH S-ZL 692 | green nose | QF 21 30.07.1967 BOAC International 500 Brands Hatch 12 Hans Herrmann | Jochen Neerpasch (replaced Kurt Ahrens) 4 4 007 2.2 Porsche System Engineering KH S-ZL 855 | modified tail | QF 12 00.10.1967 Porsche private test Nürburgring - Hans Herrmann - - 007 2.2 - KH Südschleife | completed 600 km Late 1967 Porsche private test Monza - Hans Herrmann - - 007 2.2 - KH Full circuit with chicanes 08.12.1967 Porsche press day Hockenheim - Ludovico Scarfiotti | Jo Siffert - - 007 2.2 - KH Kurz Heck | Short Tail - Unknown - - --- 2.2 - LH 14.12.1967 Porsche private test Daytona - Hans Herrmann | Rolf Stommelen | Jochen Neerpasch - - 011 2.2 - LH Accident Neerpasch | car damaged Copyright © Rob Semmeling