Notes 4: Elementary Bounds on Codes 1 Singleton Bound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

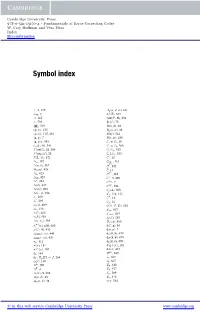

Symbol Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13170-4 - Fundamentals of Error-Correcting Codes W. Cary Huffman and Vera Pless Index More information Symbol index ⊥,5,275 Aq (n, d,w), 60 n ⊥H ,7 A (F), 517 , 165 Aut(P, B), 292 , 533 Bi (C), 75 a , p , 219 B(n d), 48 (g(x)), 125 Bq (n, d), 48 g(x) , 125, 481 B(G), 564 x, y ,7 B(t, m), 439 x, y T , 383 C1 ⊕ C2,18 αq (δ), 89, 541 C1 C2, 368 Aut(C), 26, 384 Ci /C j , 353 AutPr(C), 28 Ci ⊥C j , 353 (L, G), 521 C∗,13 μ, 187 C| , 116 Fq (n, k), 567 Cc, 145 (q), 426 C,14 2, 423 C(L), 565 ⊥ 24, 429 C ,5,469 ∗ ⊥ , 424 C H ,7 C ⊥ ( ), 427 C T , 384 C 4( ), 503 Cq (A), 308 x, y ( ), 196 Cs , 114, 122 λ i , 293 CT ,14 λ j i , 295 CT ,16 λ i (x), 609 C(X , P, D), 535 μ a , 138 d2m , 367 ν C ( ), 465 d free, 563 ν P ( ), 584 dr (C), 283 ν s , s ( i j ), 584 Dq (A), 309 π (n) C, i (x), 608, 610 d( x), 65 ρ(C), 50, 432 d(x, y), 7 , ρBCH(t, m), 440 dE (x y), 470 , ρRM(r, m), 437 dH (x y), 470 , σp, 111 dL (x y), 470 σ (x), 181 deg f (x), 101 σ (μ)(x), 187 det , 423 Dext φs , 164 , 249 φs : Fq [I] → I, 164 e7, 367 ω(x), 190 e8, 367 A , 309 E8, 428 T A ,4 Eb, 577 E Ai (C), 8, 252 n, 209 A(n, d), 48 Es , 573 Aq (n, d), 48 evP , 534 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13170-4 - Fundamentals of Error-Correcting Codes W. -

Reed-Solomon Codes

Foreword This chapter is based on lecture notes from coding theory courses taught by Venkatesan Gu- ruswami at University at Washington and CMU; by Atri Rudra at University at Buffalo, SUNY and by Madhu Sudan at MIT. This version is dated May 8, 2015. For the latest version, please go to http://www.cse.buffalo.edu/ atri/courses/coding-theory/book/ The material in this chapter is supported in part by the National Science Foundation under CAREER grant CCF-0844796. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recomendations ex- pressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation (NSF). ©Venkatesan Guruswami, Atri Rudra, Madhu Sudan, 2013. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Chapter 5 The Greatest Code of Them All: Reed-Solomon Codes In this chapter, we will study the Reed-Solomon codes. Reed-Solomoncodeshavebeenstudied a lot in coding theory. These codes are optimal in the sense that they meet the Singleton bound (Theorem 4.3.1). We would like to emphasize that these codes meet the Singleton bound not just asymptotically in terms of rate and relative distance but also in terms of the dimension, block length and distance. As if this were not enough, Reed-Solomon codes turn out to be more versatile: they have many applications outside of coding theory. -

Scribe Notes

6.440 Essential Coding Theory Feb 19, 2008 Lecture 4 Lecturer: Madhu Sudan Scribe: Ning Xie Today we are going to discuss limitations of codes. More specifically, we will see rate upper bounds of codes, including Singleton bound, Hamming bound, Plotkin bound, Elias bound and Johnson bound. 1 Review of last lecture n k Let C Σ be an error correcting code. We say C is an (n, k, d)q code if Σ = q, C q and ∆(C) d, ⊆ | | | | ≥ ≥ where ∆(C) denotes the minimum distance of C. We write C as [n, k, d]q code if furthermore the code is a F k linear subspace over q (i.e., C is a linear code). Define the rate of code C as R := n and relative distance d as δ := n . Usually we fix q and study the asymptotic behaviors of R and δ as n . Recall last time we gave an existence result, namely the Gilbert-Varshamov(GV)→ ∞ bound constructed by greedy codes (Varshamov bound corresponds to greedy linear codes). For q = 2, GV bound gives codes with k n log2 Vol(n, d 2). Asymptotically this shows the existence of codes with R 1 H(δ), which is similar≥ to− Shannon’s result.− Today we are going to see some upper bound results, that≥ is,− code beyond certain bounds does not exist. 2 Singleton bound Theorem 1 (Singleton bound) For any code with any alphabet size q, R + δ 1. ≤ Proof Let C Σn be a code with C Σ k. The main idea is to project the code C on to the first k 1 ⊆ | | ≥ | | n k−1 − coordinates. -

Fundamentals of Error-Correcting Codes W

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13170-4 - Fundamentals of Error-Correcting Codes W. Cary Huffman and Vera Pless Frontmatter More information Fundamentals of Error-Correcting Codes Fundamentals of Error-Correcting Codes is an in-depth introduction to coding theory from both an engineering and mathematical viewpoint. As well as covering classical topics, much coverage is included of recent techniques that until now could only be found in special- ist journals and book publications. Numerous exercises and examples and an accessible writing style make this a lucid and effective introduction to coding theory for advanced undergraduate and graduate students, researchers and engineers, whether approaching the subject from a mathematical, engineering, or computer science background. Professor W. Cary Huffman graduated with a PhD in mathematics from the California Institute of Technology in 1974. He taught at Dartmouth College and Union College until he joined the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at Loyola in 1978, serving as chair of the department from 1986 through 1992. He is an author of approximately 40 research papers in finite group theory, combinatorics, and coding theory, which have appeared in journals such as the Journal of Algebra, IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, and the Journal of Combinatorial Theory. Professor Vera Pless was an undergraduate at the University of Chicago and received her PhD from Northwestern in 1957. After ten years at the Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratory, she spent a few years at MIT’s project MAC. She joined the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Department of Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science as a full professor in 1975 and has been there ever since. -

An Introduction to Coding Theory

An introduction to coding theory Adrish Banerjee Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh India Feb. 6, 2017 Lecture #7A: Bounds on the size of a code Adrish Banerjee Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh India An introduction to coding theory Outline of the lecture Hamming bound Adrish Banerjee Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh India An introduction to coding theory Outline of the lecture Hamming bound Perfect codes Adrish Banerjee Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh India An introduction to coding theory Outline of the lecture Hamming bound Perfect codes Singleton bound Adrish Banerjee Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh India An introduction to coding theory Outline of the lecture Hamming bound Perfect codes Singleton bound Maximum distance separable codes Adrish Banerjee Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh India An introduction to coding theory Outline of the lecture Hamming bound Perfect codes Singleton bound Maximum distance separable codes Plotkin Bound Adrish Banerjee Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh India An introduction to coding theory Outline of the lecture Hamming bound Perfect codes Singleton bound Maximum distance separable codes Plotkin Bound Gilbert-Varshamov bound Adrish Banerjee Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh India An introduction to coding theory Bounds on the size of a code The basic problem is to find the largest code of a given length, n and minimum distance, d. -

Optimal Codes and Entropy Extractors

Department of Mathematics Ph.D. Programme in Mathematics XXIX cycle Optimal Codes and Entropy Extractors Alessio Meneghetti 2017 University of Trento Ph.D. Programme in Mathematics Doctoral thesis in Mathematics OPTIMAL CODES AND ENTROPY EXTRACTORS Alessio Meneghetti Advisor: Prof. Massimiliano Sala Head of the School: Prof. Valter Moretti Academic years: 2013{2016 XXIX cycle { January 2017 Acknowledgements I thank Dr. Eleonora Guerrini, whose Ph.D. Thesis inspired me and whose help was crucial for my research on Coding Theory. I also thank Dr. Alessandro Tomasi, without whose cooperation this work on Entropy Extraction would not have come in the present form. Finally, I sincerely thank Prof. Massimiliano Sala for his guidance and useful advice over the past few years. This research was funded by the Autonomous Province of Trento, Call \Grandi Progetti 2012", project On silicon quantum optics for quantum computing and secure communications - SiQuro. i Contents List of Figures......................v List of Tables....................... vii Introduction1 I Codes and Random Number Generation7 1 Introduction to Coding Theory9 1.1 Definition of systematic codes.............. 16 1.2 Puncturing, shortening and extending......... 18 2 Bounds on code parameters 27 2.1 Sphere packing bound.................. 29 2.2 Gilbert bound....................... 29 2.3 Varshamov bound.................... 30 2.4 Singleton bound..................... 31 2.5 Griesmer bound...................... 33 2.6 Plotkin bound....................... 34 2.7 Johnson bounds...................... 36 2.8 Elias bound........................ 40 2.9 Zinoviev-Litsyn-Laihonen bound............ 42 2.10 Bellini-Guerrini-Sala bounds............... 43 iii 3 Hadamard Matrices and Codes 49 3.1 Hadamard matrices.................... 50 3.2 Hadamard codes..................... 53 4 Introduction to Random Number Generation 59 4.1 Entropy extractors................... -

Optimal Locally Repairable Codes of Distance 3 and 4 Via Cyclic Codes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CWI's Institutional Repository Optimal locally repairable codes of distance 3 and 4 via cyclic codes Yuan Luo,∗ Chaoping Xing and Chen Yuan y Abstract Like classical block codes, a locally repairable code also obeys the Singleton-type bound (we call a locally repairable code optimal if it achieves the Singleton-type bound). In the breakthrough work of [14], several classes of optimal locally repairable codes were constructed via subcodes of Reed-Solomon codes. Thus, the lengths of the codes given in [14] are upper bounded by the code alphabet size q. Recently, it was proved through extension of construction in [14] that length of q-ary optimal locally repairable codes can be q + 1 in [7]. Surprisingly, [2] presented a few examples of q-ary optimal locally repairable codes of small distance and locality with code length achieving roughly q2. Very recently, it was further shown in [8] that there exist q-ary optimal locally repairable codes with length bigger than q + 1 and distance propositional to n. Thus, it becomes an interesting and challenging problem to construct new families of q-ary optimal locally repairable codes of length bigger than q + 1. In this paper, we construct a class of optimal locally repairable codes of distance 3 and 4 with un- bounded length (i.e., length of the codes is independent of the code alphabet size). Our technique is through cyclic codes with particular generator and parity-check polynomials that are carefully chosen. -

Algebraic Geometric Codes: Basic Notions Mathematical Surveys and Monographs

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/surv/139 Algebraic Geometric Codes: Basic Notions Mathematical Surveys and Monographs Volume 139 Algebraic Geometric Codes: Basic Notions Michael Tsfasman Serge Vladut Dmitry Nogin American Mathematical Society EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Jerry L. Bona Peter S. Landweber Michael G. Eastwood Michael P. Loss J. T. Stafford, Chair Our research while working on this book was supported by the French National Scien tific Research Center (CNRS), in particular by the Inst it ut de Mathematiques de Luminy and the French-Russian Poncelet Laboratory, by the Institute for Information Transmis sion Problems, and by the Independent University of Moscow. It was also supported in part by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, projects 99-01-01204, 02-01-01041, and 02-01-22005, and by the program Jumelage en Mathematiques. 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 14Hxx, 94Bxx, 14G15, 11R58; Secondary 11T23, 11T71. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/surv-139 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tsfasman, M. A. (Michael A.), 1954- Algebraic geometry codes : basic notions / Michael Tsfasman, Serge Vladut, Dmitry Nogin. p. cm. — (Mathematical surveys and monographs, ISSN 0076-5376 ; v. 139) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8218-4306-2 (alk. paper) 1. Coding theory. 2. Number theory. 3. Geometry, Algebraic. I. Vladut, S. G. (Serge G.), 1954- II. Nogin, Dmitry, 1966- III. Title. QA268 .T754 2007 003'.54—dc22 2007061731 Copying and reprinting. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit libraries acting for them, are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy a chapter for use in teaching or research. -

ELEC 619A Selected Topics in Digital Communications: Information Theory

ELEC 519A Selected Topics in Digital Communications: Information Theory Hamming Codes and Bounds on Codes Single Error Correcting Codes 2 Hamming Codes • (7,4,3) Hamming code 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 GIP | 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 • (7,3,4) dual code 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 T HPI -| 1011010 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 3 • The minimum distance of a code C is equal to the minimum number of columns of H which sum to zero • For any codeword c h0 h T 1 cH [c,c,...,c01 n1 ] ch 0011 ch ...c n1n1 h 0 hn1 where ho, h1, …, hn-1 are the column vectors of H T • cH is a linear combination of the columns of H 4 Significance of H • For a codeword of weight w (w ones), cHT is a linear combination of w columns of H. • Thus there is a one-to-one mapping between weight w codewords and linear combinations of w columns of H that sum to 0. • The minimum value of w which results in cHT=0, i.e., codeword c with weight w, determines that dmin = w 5 Distance 1 and 2 Codes • (5,2,1) code 10100 10110 HG= 10010 = 01000 00001 • (5,2,2) codes 11100 10110 HG= 11010 = 01110 00001 6 (7,4,3) Code • A codeword with weight dmin = 3 is given by the first row of G: c = 1000011 • The linear combination of the first and last 2 columns in H gives T T T T (011) +(010) +(001) = (000) • Thus a minimum of 3 columns (= dmin) are required to get a zero value for cHT 7 Binary Hamming Codes Let m be an integer and H be an m (2m - 1) matrix with columns which are the non-zero distinct elements from Vm. -

Generalized Sphere-Packing and Sphere-Covering Bounds on the Size

1 Generalized sphere-packing and sphere-covering bounds on the size of codes for combinatorial channels Daniel Cullina, Student Member, IEEE and Negar Kiyavash, Senior Member, IEEE Abstract—Many of the classic problems of coding theory described. Erasure and deletion errors differ from substitution are highly symmetric, which makes it easy to derive sphere- errors in a more fundamental way: the error operation takes packing upper bounds and sphere-covering lower bounds on the an input from one set and produces an output from another. size of codes. We discuss the generalizations of sphere-packing and sphere-covering bounds to arbitrary error models. These In this paper, we will discuss the generalizations of sphere- generalizations become especially important when the sizes of the packing and sphere-covering bounds to arbitrary error models. error spheres are nonuniform. The best possible sphere-packing These generalizations become especially important when the and sphere-covering bounds are solutions to linear programs. sizes of the error spheres are nonuniform. Sphere-packing and We derive a series of bounds from approximations to packing sphere-covering bounds are fundamentally related to linear and covering problems and study the relationships and trade-offs between them. We compare sphere-covering lower bounds with programming and the best possible versions of the bounds other graph theoretic lower bounds such as Turan’s´ theorem. We are solutions to linear programs. In highly symmetric cases, show how to obtain upper bounds by optimizing across a family of including many classical error models, it is often possible to channels that admit the same codes. -

Classification of Perfect Codes and Minimal Distances in the Lee Metric

Master Thesis Classification of perfect codes and minimal distances in the Lee metric Naveed Ahmed 1982-06-20 Waqas Ahmed 1982-09-13 Subject: Mathematics Level: Advance Course code: 5MA12E Abstract Perfect codes and minimal distance of a code have great importance in the study of theory of codes. The perfect codes are classified generally and in particular for the Lee met- ric. However, there are very few perfect codes in the Lee metric. The Lee metric has nice properties because of its definition over the ring of integers residue modulo q.Itis conjectured that there are no perfect codes in this metric for q > 3, where q is a prime number. The minimal distance comes into play when it comes to detection and correction of error patterns in a code. A few bounds on the number of codewords and minimal distance of a code are discussed. Some examples for the codes are constructed and their minimal distance is calculated. The bounds are illustrated with the help of the results obtained. Key-words: Hamming metric; Lee metric; Perfect codes; Minimal distance iii Acknowledgments This thesis is written as a part of the Degree of Master of Science in Mathematics at Linnaeus University, Sweden. It is written at the School of Computer Science, Physics and Mathematics. We would like to thank our supervisor Per-Anders Svensson who has been very sup- porting throughout the whole period. We are also obliged to him for giving us chance to work under his supervision. We would also like to thank our Program Manager Marcus Nilsson who has been very helpful and very cooperative within all matters, and also all the respectable faculty members of the department. -

MAS309 Coding Theory

MAS309 Coding theory Matthew Fayers January–March 2008 This is a set of notes which is supposed to augment your own notes for the Coding Theory course. They were written by Matthew Fayers, and very lightly edited my me, Mark Jerrum, for 2008. I am very grateful to Matthew Fayers for permission to use this excellent material. If you find any mistakes, please e-mail me: [email protected]. Thanks to the following people who have already sent corrections: Nilmini Herath, Julian Wiseman, Dilara Azizova. Contents 1 Introduction and definitions 2 1.1 Alphabets and codes . 2 1.2 Error detection and correction . 2 1.3 Equivalent codes . 4 2 Good codes 6 2.1 The main coding theory problem . 6 2.2 Spheres and the Hamming bound . 8 2.3 The Singleton bound . 9 2.4 Another bound . 10 2.5 The Plotkin bound . 11 3 Error probabilities and nearest-neighbour decoding 13 3.1 Noisy channels and decoding processes . 13 3.2 Rates of transmission and Shannon’s Theorem . 15 4 Linear codes 15 4.1 Revision of linear algebra . 16 4.2 Finite fields and linear codes . 18 4.3 The minimum distance of a linear code . 19 4.4 Bases and generator matrices . 20 4.5 Equivalence of linear codes . 21 4.6 Decoding with a linear code . 27 5 Dual codes and parity-check matrices 30 5.1 The dual code . 30 5.2 Syndrome decoding . 34 1 2 Coding Theory 6 Some examples of linear codes 36 6.1 Hamming codes . 37 6.2 Existence of codes and linear independence .