Valentin Silvestrov Symphonies 4 & 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ukrainian Weekly 1987, No.46

www.ukrweekly.com Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.. a fraternal non-profit association| IraInian WeekI V Vol. LV No,46 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 1987 25 cents NY Times correspondenfs stories LubachIvsky seeks reconciliation reflected Soviet line, says scholarwit h Russian Orthodox Church Dr. Mace revealed this finding in a Calls for mutual forgiveness primate's call for reconciliation was first Document revealspape r he was to present on Friday, reported in the United States by the November 13, at a conference on JERSEY CITY, N.J. - Cardinal Associated Press. However, the AP's secret agreement "Recognition and Denial of Geno Myroslav Ivan Lubachivsky, leader of quotes from Cardinal Lubachivsky's cide and Mass Killing in the 20th the Ukrainian Catholic Church, has speech were not quite accurate. JERSEY CITY, N. J. - New York called for reconciliation with the Rus Moreover, the AP incorrectly quoted Times correspondent Walter Du- Century." An advance copy of the paper, along with a photocopy of the sian nation and the Moscow Patriar the cardinal as saying that he hoped to ranty's dispatches from the Soviet chate of the Russian Orthodox Church. return to Ukraine next year to celebrate Union always reflected "the official U.S. Embassy document, was re ceived by The Ukrainian Weekly. In a speech delivered Friday, Novem liturgy **in my cathedral in Kiev."There opinion of the Soviet regime and not ber 6, the cardinal said: is no Ukrainian Catholic cathedral in his own," according to a declassified Dr. Mace concludes: "Duranty's own words make it clear that he was "In keeping with Christ's spirit, we Kiev; furthermore Cardinal Lubachiv U.S. -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

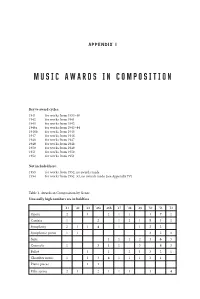

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

Russian Piano Sonatas Volume 1 Balakirev Glazunov Kosenko

RUSSIAN PIANO SONATAS VOLUME 1 BALAKIREV GLAZUNOV KOSENKO Vincenzo Maltempo BALAKIREV · GLAZUNOV · KOSENKO 20th Century Russian Piano Sonatas MILY BALAKIREV: Piano Sonata No.2 in B flat minor Op.102 The Ukrainian composer and pianist Viktor Stepanovych Kosenko (1896- 1. Andantino 6’47 1938) was born to an affluent military family in St Petersburg. Relatively 2. Mazurka, moderato 5’34 forgotten today, despite a catalogue (covering the years 1910-37) embracing 3. Intermezzo, larghetto 3’59 concertos, chamber works, piano music and folk song arrangements, he 4. Finale, allegro non troppo, ma con fuoco 7’52 studied in Warsaw with the pre-eminent Chopin specialist Aleksander Michałowski, whose own teachers had included Moscheles, Reinecke and ALEXANDER GLAZUNOV: Piano Sonata No.2 in E minor Op.75 Tausig (1908-14). With the onset of the First World War, Konsenko moved 5. Moderato-poco più mosso 9’06 back to St Petersburg, where he was enrolled at the Conservatory (1914- 6. Scherzo, allegretto 6’22 18). Here his composition and playing briefly caught Glazunov’s attention 7. Finale, allegro moderato 9’47 and encouragement. On graduation Kosenko joined his family in Zhytomyr, north-western Ukraine (Richter’s birthplace – he was then three, living VIKTOR KOSENKO: Piano Sonata No.2 in C sharp minor Op.14 with his aunt), taking up appointments at the Music Technicum, becoming 8. Andante con moto 9’37 director of the city’s Music School, and co-founding the Leontovych 9. Moderato assai espressivo 5’04 Musical Society. He married in 1920. Nine years later - following a period of 10. -

March 1981 Accelerating a Trend Already Ukrainian Studies University Course Later in His Vol

' . Central - UNt>£esTAMD THE OF WOMElJ ! Ukrainian studies in jeopardy? Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Enrollments Drop decade or so in- According to a research factors alone. Enrolment, or ment by 28 percent. This enrol- in the next its accelerated a dicates that there will be report recently done for the rather the lack of it, is taking ment trend has concentration of Canadian univer- Canadian Institute of Ukrainian toll. We know of a number of process of problems for Studies by Bohdan departments where, as a result Ukrainian university course sities in general and Ukrainian Krawchenko, enrolment in of poor enrolment, courses had enrolment in western Canada: programmes in particular. First, percent of the total enrol- the general economic climate is courses in Ukrainian studies to be cancelled. At the Universi- 67 1976-77 79 percent students into was substantially lower in 1979- ty of Windsor, for example, the ment in and propelling 1 979-80 accounted for by rather 80 than for the comparable problem is so serious that in was professional faculties universities. Put in than arts courses. period in 1976-77. "courses in Ukrainian will be western general lack of the University of Secondly, as a result of In a follow-up study to his suspended next year for another way, University of the 1977 report on Ukrainian enrolment." Manitoba and the demographic trends in have higher population, the Studies at Canadian univer- The tale of declining enrol- Alberta each Canadian arts in Ukrainian studies number of 1 8-24 year olds (the sities, Professor Krawchenko ment, especially in enrolments eight eastern critical university found that despite the introduc- faculties, is a familiar one and courses than all group for universities com- attendance) rather tion of courses in Ukrainian has given cause for alarm to Canadian will decline average enrolment studies at Concordia University educators across Canada. -

Krysa Discography

OLEH KRYSA DISCOGRAPHY BIS label Ernest Bloch. Violin Concerto Oleh Krysa, Violin Malmo Symphony Orchestra, Sakari Oramo, Conductor Sofia Gubaidulina. “Offertorium”. Concerto for Violin and Orchestra “Rejoce!” Sonata for Violin and Cello Oleh Krysa, Violin, Torleif Thedeen, Cello Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, James de Preist, Conductor Alfred Schnittke . Violin Concertos Nos. 3 & 4 Oleh Krysa, Violin Malmo Symphony Orchestra, Eri Klas, Conductor Alfred Schnittke. Concerto Grosso No. 2 for Violin, Cello and Orchestra Oleh Krysa, Violin, Torleif Thedeen, Cello Malmo Symphony Orchestra, Lev Markiz, Conductor Alfred Schnittke. Chamber Music Prelude in memoriam Dmitri Shostakovih for Two Violins Moz-Art for Two Violins Stille Musik for Violin and Cello Madrigal in memoriam Oleg Kagan for solo Violin Madrigal in memoriam Oleg Kagan for solo Cello Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano Oleh Krysa, Violin, Alexandr Fisher, Violin, Torleif Thedeen, Cello, Tatiana Tchekina, Piano Erwin Schulhoff. Sonata for solo Violin Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2 Duo for Violin and Cello Oleh Krysa, Violin, Tatiana Tchekina, Piano, Torleif Thedeen, Cello Maurice Ravel. Sonata for Violin and Cello Bohuslav Martinu. Duo No. 1 for Violin and Cello Arthur Honegger. Sonatina for Violin and Cello Erwin Schulhoff. Duo for Violin and Cello Oleh Krysa, Violin, Torleif Thedeen, Cello -2- TNC RECORDINGS label Ludwig van Beethoven. Violin Concerto in D Major, op. 61 Oleh Krysa, Violin Kiev Camerata, Virko Baley, Conductor Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. Violin Concerto in E minor, op. 64 Johannes Brahms. Violin Concerto in D Major, op. 77 Giovanni Battista Viotti. Violin Concerto No. 22 in A minor Max Bruch. Scottish Fantasy, op. -

Valentin Silvestrov (B

SILVESTROV Moments of Memory II Serenade • The Messenger – 1996 Farewell Serenade • Silent Music Iryna Starodub, Piano Kiev Virtuosi • Dmitry Yablonsky Valentin Silvestrov (b. 1937) Moments of Memory II • Serenade • The Messenger – 1996 • Farewell Serenade • Silent Music ‘I do not write new music. My music is a response to and flickers of memory and dialogues with the past in the motif begins to dominate the material and the music gains Mozartian phrases, marked ‘as if enveloped in mist’. an echo of what already exists’. This remark by Ukrainian dramatic narratives of his subsequent scores. in intensity, culminating in a sequence of sonorous cluster These shadowy statements give the piece the flavour of a composer Valentin Silvestrov is pertinent to many of the In recent years Silvestrov has developed his own chords. In the wake of this climactic episode, there is a pure and delicate 18th-century sonatina. However, wistful, seemingly partially-recalled vignettes contained in version of postmodernism. He describes it as gentle, finely wrought passage in E flat minor. The closing Silvestrov is not content merely to offer an effective this programme. ‘metamusic’, a shortened form of ‘metaphorical music’. section is avowedly tonal. After a brief moment of pastiche. He recasts his classical melodies as a series of Silvestrov was born on 30 September 1937 in Kiev. This universal language is acutely sensitive to other bitonality, the work ebbs away in F major. shifting impressions by constantly altering minutely the He began private music lessons at the age of 15. From musics and acts as a kind of postlude to them. -

01-ALEA Program May 3, 2019

F o r t y - f i r s t S e a s o n ALEA III 2 0 1 8 - 2 0 19 2018 – 2019 SEASON (continues from previous page) Memorial Gathering Saturday, April 13, 2019, 1:00 p.m. Annunciation Cathedral ALEA III 514 Parker Street, Boston A celebration of Theodore Antoniou’s life and work. -------------------- Music from Ukraine and Russia Friday, May 3, 2019, 8:00 p.m. Theodore Antoniou, Marsh Chapel Founder 735 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston Admission is Free Contemporary Music Ensemble Ukrainian pianist and conductor Alex Poliykov in residence at Boston University since 1979 presents a program featuring works by Ukrainian and Russian Composers. -------------------- A Celebration of Europe Day 2019 Thursday, May 9, 2019, 7:30 p.m. Old South Church Music from Ukraine and Russia 645 Boylston Street, Boston Admission is Free Curated by Aleksandr Poliykov Curated by the Consulate General of Ireland in Boston An evening with music to celebrate Europe Day, May 9th, 2019 -------------------- Marsh Chapel 735 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston ALEA III 2019 Summer Meetings August 23 – September 1, 2019 Island of Naxos, Greece A workshop for composers, performers, audio/visual and other artists to present their work and collaborate in new projects to be Friday, May 3, 2019 featured in 2019, 2020 and 2021 events. Daily meetings and concerts. FOUNDER ALEA III Theodore Antoniou 2018 – 2019 SEASON BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD OF ADVISORS President Mario Davidovsky Young Composers Workshop 2019 Margaret McAllister Spyros Evangelatos February 15-24, 2019 John Harbison Athens, Greece Vice President Leonidas Kavakos Panos Liaropoulos Dimitris Nanopoulos The second phase of an ongoing project that started in August 2018 Krzysztof Penderecki and will be completed with a USA tour in Spring of 2021. -

Мистецтвознавство Paliichuk I. GENRE and STYLISTIC TRENDS

Мистецтвознавство Paliichuk I. 9. НХМУ (Національний художній музей України). ДАФ. Ф. 28. Оп. 1. Од. зб. 19, арк. 1. 10. НХМУ (Національний художній музей України). ДАФ. Ф. 28. Оп. 1. Од. зб. 24, арк. 1. 11. НХМУ (Національний художній музей України). ДАФ. Ф. 28. Оп. 1. Од. зб. 42, арк. 1. 12. Павельчук І. А. Мотив с деревом в краєвидах Абрама Маневича із збірки Національно художнього музею. Ми- стецтвознавчі записки : зб. наук. праць. Київ : Міленіум, 2014. Вип. 26. С. 249–259. 13. Павельчук І. А. Традиції формального образотворення Японії у практиці французьких постімпресіоністів 1880– 1890-х років (до проблем асиміляції постімпресіонізму в мистецтві України ХХ–ХХІ століть). Вісник Харківської державної ака- демії дизайну і мистецтв. Харків : ХДАДМ, 2017. ғ 4. С. 57–65. 14. Поспелов Г. Русский сезаннизм начала XX века. Поль Сезанн и русский авангард начала XX века : каталог / ред. А. Г. Костеневич. Санкт-Петербург : Славия, 1998. С. 158–166. 15. Сезанн П. Переписка. Воспоминания современников / сост., вступ. ст., примеч. Н. В. Яворской ; пер. : Е. Р. Классон, Л. Д. Липман. Москва : Искусство, 1972. 368 с. 16. Тугендхольд Я. Итоги сезона (Письмо из Парижа). Аполлон. 1911. ғ 6. С. 69–70. 17. Cezannism. InCoRM. 2010. URL: http://www.incorm.eu/styles.html (дата звернення : 24.12.2018). 18. Mourey G. Abraham Manievitch. Exposition Manievitch : Catalogue des Peintures de Abraham Manievitch / Galerie Du- rand-Ruel. Paris, 1913. 16 p. 19. Novotny F. Cézanne. Vienna : Phaidon, 1937. 20 p. : 126 plates. Стаття надійшла до редакції 10.05.2019 р. UDC 785.7:788.1/.4 Paliichuk Iryna© Ph.D. in History of Arts, assistant professor of Ukrainian music and folk instrumental art of V. -

КУЛЬТУРА УКРАЇНИ CULTURE of UKRAINE Cерія: Мистецтвознавство Series: Art Criticism Збірник Наукових Праць Scientifi C Journal

ISSN 2410-5325 (print) 1 ISSN 2522-1140 (online) Міністерство культури України Харківська державна академія культури Ministry of Culture of Ukraine Kharkiv State Academy of Culture КУЛЬТУРА УКРАЇНИ CULTURE OF UKRAINE Cерія: Мистецтвознавство Series: Art Criticism Збірник наукових праць Scientifi c Journal За загальною редакцією В. М. Шейка Editor-in-Chief V. Sheyko Засновано в 1993 р. Founded in 1993 Випуск 61 Issue 61 Харків, ХДАК, 2018 Kharkiv, KhSAC, 2018 УДК [008+78/79](062.552) К90 Засновник і видавець — Харківська Founder and publisher — Kharkiv State державна академія культури Academy of Culture Свідоцтво про державну реєстрацію Certificate of state registration of printed друкованого засобу масової інформації mass media, series КВ №13567-2540Р of серія КВ №13567-2540Р від 26.12.2007 р. 26.12.2007 Затверджено наказом Міністерства освіти Approved by the Ministry of Education and і науки України № 1328 від 21.12.2015 р. Science of Ukraine № 1328 of 21.12.2015 as як фахове видання з культурології a Specialist Culturology and Art Criticism та мистецтвознавства Publication Рекомендовано до друку Recommended for publication рішенням ученої ради by the decision of the Academic Board Харківської державної академії культури of the Kharkiv State Academy of Culture (протокол № 10 від 25.05.2018) (record № 10, 25.05.2018) Збірник поданий на порталі The journal is submitted to the portal (http://www.nbuv.gov.ua) (http://www.nbuv.gov.ua) in the information в інформаційному ресурсі «Наукова resource “Scientific Periodicals Ukraine”, періодика України», у реферативних базах in bibliographic databases “Ukrainika «Україніка наукова» та «Джерело» scientific” and “Dzherelo” Індексується в наукометричній базі Indexed in the bibliographic database «Російський індекс наукового цитування» “Russian Science Citation Index” та в пошуковій системі Google Scholar and in the Web search engine Google Scholar ХДАК є представленим учасником PILA KhSAC is the Sponsored Member of PILA Веб-сайт збірника: Website of the journal: http://ku-khsac.in.ua http://ku-khsac.in.ua Е-mail ред.-видавн. -

Zhytomyr from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°15′0″N 28°40′0″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Zhytomyr From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°15′0″N 28°40′0″E Zhytomyr (Ukrainian: Жито́мир pronounced [ʒɪˈtɔmɪr], Russian: Жито́мир, Zhitomir, Polish: Navigation Zhitomir) is a city in the North of the western half of Ukraine. It Zhytomyr ,זשיטאָמיר :Żytomierz, Yiddish Житомир Main page is the administrative center of the Zhytomyr Oblast (province), as well as the administrative Contents center of the surrounding Zhytomyr Raion (district). Note that the city of Zhytomyr is not a part Featured content of the Zhytomyr raion: the city itself is designated as its own separate raion within the oblast; Current events moreover Zhytomyr consists of two so-called "raions in a city": the Bohunskyi raion and the Random article Koroliovskyi raion (named in honour of Sergey Korolyov). Zhytomyr is located at around Donate to Wikipedia 50°16′N 28°40′E, occupying an area of 65 km2 (25 sq mi). The current estimated population is 277,900 (as of 2005). Interaction Zhytomyr is a major transportation hub. The city lies on a historic route linking the city of Kiev Help with the west through Brest. Today it links Warsaw with Kiev, Minsk with Izmail, and several About Wikipedia major cities of Ukraine. Zhytomyr was also the location of Ozerne (airbase), a key Cold War Kyivska (Kiev) street looking West toward St. Michael's Church. Photo early 1900s. Community portal strategic aircraft base located 11 km (6.8 mi) southeast of the city. Recent changes Important economic activities of Zhytomyr include lumber milling, food processing, granite Contact page quarrying, metalworking, and the manufacture of musical instruments.[1] Zhytomyr Oblast is the main center of the Polish minority in Ukraine, and in the city itself Toolbox there is a large Roman-Catholic Polish cemetery, founded in 1800. -

FINNISH and BALTIC SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present

FINNISH AND BALTIC SYMPHONIES From The 19th Century To The Present A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman KALEVI AHO (b. 1949) FINLAND Born in Forssa. He studied composition at the Sibelius Academy under Einojuhani Rautavaara. He continued his studies in Berlin with Boris Blacher. He has taught music theory at the University of Helsinki and had a professorship at the Sibelius Academy and has also written articles on musical subjects. He has composed operas as well as a large body of works for orchestra and chamber groups. His unrecorded Symphonies are No. 6 (1979-80) and Chamber Symphonies Nos. 1 for 20 Strings (1976) and 2 for 20 strings (1995-6). He has also written more than a dozen Concertos for various instruments. Symphony No. 1 (1969) Osmo Vänskä/Lahti Symphony Orchestra ( + Violin Concerto and Silence) BIS CD-396 (1994) Symphony No. 2 for String Orchestra (1970, rev. 1995) Osmo Vänskä/Lahti Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 7) BIS CD-936 (1998) Symphony No. 3 for Violin and Orchestra (Sinfonia Concertante No. 1) (1971-3) Osmo Vänskä/Jaakko Kuusisto (violin)/Lahti Symphony Orchestra ( + Mussorgsky/Aho: Songs and Dances of Death) BIS CD-1186 (2003) Symphony No. 4 (1972-3) Paavo Rautio/Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra FINNLEVY SFX 44 (LP) (1977) Osmo Vänskä/Lahti Symphony Orchestra ( + Chinese Songs) BIS CD-1066 (2000) Symphony No. 5 (1975-6) Max Pommer/Leipzig Radio Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 7) ONDINE ODE 765 (1991) Symphony No. 7 "Insect Symphony" (1988) Max Pommer/Leipzig Radio Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 5) MusicWeb International Last update: August 2020 Finnish & Baltic Symphonies ONDINE ODE 765 (1991) Osmo Vänskä/Lahti Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. -

A Stylistic Analysis of Reinhold Glière's 25 Preludes for Piano, Op. 30

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2020 A Stylistic Analysis of Reinhold Glière’s 25 Preludes for Piano, Op. 30 Sunjoo Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Lee, S.(2020). A Stylistic Analysis of Reinhold Glière’s 25 Preludes for Piano, Op. 30. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5946 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Stylistic Analysis of Reinhold Glière’s 25 Preludes for Piano, Op. 30 by Sunjoo Lee Bachelor of Music Kyung Hee University, 2002 Master of Music University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Master of Music University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctoral of Musical Arts in Piano Pedagogy School of Music University of South Carolina 2020 Accepted by: Scott Price, Major Professor, Director of Dissertation Sara M. Ernst, Committee Member J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Philip Bush, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Sunjoo Lee, 2020 All rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To Dr. Reid Alexander (May 27, 1949 – November 18, 2015), a one of a kind professor and academic father figure. Without you, I would not have gotten to this point. I still remember our conversation about my first pedagogy class with you in my very first semester in the United States.