Peter Maxwell Davies in the 1950S: a Conversation with the Composer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

SIR PETER MAXWELL DAVIES: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1955: “Burchiello” for sixteen percussion instruments “Opus Clavicembalisticum(Sorabji)” for orchestra “Work on a Theme by Thomas Tompkins” for orchestra 1957: St. Michael”-Sonata for seventeen wind instruments, op.6: 17 minutes 1958: “Prolation” for orchestra, op.8: 20 minutes 1959: “Five Canons” for school/amateur orchestra “Pavan and Galliard” for school/amateur orchestra “Variations on a Theme for Chords” for school/amateur orchestra 1959/76: Five Klee Pictures for orchestra, op.12: 10 minutes + (Collins cd) 1960: Three Pieces for junior orchestra 1961: Fantasy on the National Anthem for school/amateur orchestra 1962: First Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op.19: 11 minutes Sinfonia for chamber orchestra, op. 20: 23 minutes + Regis d) 1963: “Veni Sancte Spiritus” for soprano, contralto, tenor, baritone, chorus and orchestra, op.22: 20 minutes 1964: Second Fantasia on an “In Nomine” of John Taverner for orchestra, op. 23: 39 minutes + (Decca cd) 1967: Songs to Words by Dante for baritone and small orchestra 1969: Foxtrot “St. Thomas Wake” for orchestra, op.37: 20 minutes + (Naxos cd) Motet “Worldes Bliss” for orchestra, op.38: 37 minutes 1971: Suite from “The Boyfriend” for small orchestra, op.50b: 26 minutes * + (Collins cd) 1972: “Walton Tribute” for orchestra Masque “Blind Man’s Buff” for soprano or treble, mezzo-soprano, mime and small orchestra, op.51: 20 minutes 1973: “Stone Liturgy-Runes from a House of the Dead” for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, -

The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Insight - University of Cumbria The Persistence of Parody in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies Richard E McGregor It’s all about time. Indeed there is not a single piece of musical composition that is not in some way about time. And for Davies the manipulation of time is rooted in his understanding of late Medieval and early Renaissance musical techniques and practices refracted through post 12-note pitch manipulation. In this article I take to task the uncritical use of terminology in relation to the music of Peter Maxwell Davies. Though my generating text is the quotation from John Warnaby’s 1990 doctoral thesis: Since parody is implied in the notion of using pre-existing material as a creative model, it can be argued that, as traditionally understood, it is rarely absent from Maxwell Davies’s music[1] this is in no wise a criticism of Warnaby for whom I have much respect, and especially his ability to be able to perceive patterns, trends and unifying features between works and across extended periods of time. Rather, it is a commentary on particular aspects of Davies’s music which are often linked together under the catch-all term ‘parody’: EXAMPLE 1: Dali’s The Persistence of Memory[2] I take as my starting point the painting The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali, a painting which operates on a number of levels, the most obvious, because of the immediate imagery, being that is has something to do with time. -

Euromac 9 Extended Abstract Template

9th EUROPEAN MUSIC ANALYSIS CONFERENC E — E U R O M A C 9 Hei Yeung Lai The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong [email protected] Goehr’s Piano Sonata through a Transformational Lens the introductory theme also acts as a germ that ‘contains a latent set of ABSTRACT relationships that the themes unfold’, which is depicted by some isographic transformational networks. Background On the other hand, the endings of each section of the Sonata feature different tetrachordal presentations. Specifically, the (013) trichord is Alexander Goehr’s interest in serialism has its root in the embedded in all of these structural tetrachords, which further asserts twelve-note compositional trend in the post-war environment and his the importance of this abstract intervallic motive at the structural level. particular family and cultural background. His Piano Sonata is his first The application of the Klumpenhouwer networks relates these composition to have secured a performance in an international context, structural harmonies by means of isographic networks, which binds the one that de facto launched his professional career. Apart from being chronological structural closures into a complex of relationships and inspired by the rhythmic characteristics of Bartók and Messiaen, Goehr hence reveals the ‘deep structure’ of the Sonata. points out that Liszt’s Piano Sonata and Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony also informed his Sonata, ‘which contained [his] first Implications experiment in the combination of twelve-note row and modal harmony’ The application of transformational analysis, along with that of (Goehr and Wintle 1992, 168-169). The subtitle ‘in memory of Serge Klumpenhouwer net, on Goehr’s Sonata, a novel approach conducted Prokofiev’ in the published scores and the melodic reference to here for the first time, reveals an intricate array of functional Prokofiev’s Seventh Piano Sonata also confirm Goehr’s reference to the relationships among different themes and structural entities, which Russian composer (Rupprecht 2015, 124). -

RCM and Its Community, Part 2: the Hair-Raising Exploits of RCM Staff

The Magazine for the Royal College of MusicI Autumn 2010 RCM and its community, part 2: The hair-raising exploits of RCM staff What’s inside... Welcome to upbeat… Welcome to the second of two special bumper issues of Upbeat, celebrating the extraordinary RCM community. Contents Following a summer issue devoted to RCM students, we now turn our 4 In the news attention to RCM staff. When they’re not here in Prince Consort Road, RCM Latest news from the RCM professors and administrative staff can be found running festivals, working with charities, collaborating with composers, producing CDs and DVDs, and 9 Hello and goodbye! performing in the widest possible variety of locations. They also perform under We welcome our new arrivals this the widest possible variety of names, so if you want to know the meaning of academic year and bid farewell to curious phrases such as My Gosh Marvellous, The G Project and Colombus three key members of staff Giant, then read on! 10 Staff stories Huge thanks to the many staff who submitted their stories, including those Upbeat meets with a variety of we sadly couldn’t quite fit in: we would love to have had the space to tell you RCM staff to explore ways they are contributing to music today about a dramatic year at Kathron Sturrock’s Fibonacci Festival, and Catherine Jack’s appearance on Centre Court at Wimbledon, but that would have blown 18 The big give the budget! With thanks to… As usual, the rest of Upbeat is packed with news from around the RCM. -

Peter Maxwell Davies Eigentliche Grund Dafür Klar: Ich Wollte Keinen Dicken Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac

557400 bk Max 14/7/08 10:53 Page 4 diszipliniert, wobei, wie ich glaube, durch die recht schwarzen Schluss-Strich ziehen, wollte nicht, dass das genaue und komplexe Arbeit mit magischen Quadraten ein letztes Quartett sein soll. Ich musste die Tür offen einige Ordnung entstanden ist. lassen: Mir hat die Arbeit an den Naxos-Quartetten so PETER Ich habe auch auf das dritte Naxos Quartet viel Freude gemacht (und ich habe dabei vielleicht sogar verwiesen. Dort habe ich dem Violoncello einen Vers das eine oder andere gelernt), dass theoretisch daraus von Michelangelo unterlegt, der mit den Worten noch mehr entstehen könnte. MAXWELL DAVIES beginnt: Caro me il sonno, e più l’esser di sasso („Der Eine weitere Versuchung bestand darin, in einer Schlaf ist mir teuer, und von Stein zu sein, ist teurer“). feierlichen Abschiedssequenz auf jedes der vorigen In diesem Gedicht beklagt der Dichter, dass er im Quartette anzuspielen, wie ich das im letzten der zehn römischen Exil leben muss – fern seines Heimatstaates Strathclyde Concertos für das Scottish Chamber Naxos Quartets Nos. 9 and 10 Florenz, dessen Regierung er wegen ihrer Orchestra getan hatte. Ich hielt stand. Zwar ist der dritte „Rechtsverletzung und Schande“ tadelt. Satz als Passamezzo Farewell bezeichnet, doch ohne Der zweite Satz ist auch jetzt (wie die ursprüngliche alle Wehmut – wenngleich es durchaus Rückblicke gibt. Maggini Quartet Skizze) ein Largo, in dem der erste Teil des Kopfsatzes Der erste Satz ist ein Broken Reel. Die Umrisse der langsam durchgeführt wird, heftig unterbrochen von der Tanzform sind vorhanden, die Rhythmen aber sind verworfenen Musik, die hier integriert und verstärkt gebrochen, derweil hinter der barocken Oberfläche eine erscheint. -

Alexander Goehr “Fings Ain’T Wot They Used T’Be”

Archive zur Musik des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts Band 13 Alexander Goehr “Fings ain’t wot they used t’be” On behalf of the Archives of the Akademie der Künste edited by Werner Grünzweig wolke First Edition 2012 Copyright © by Archiv der Akademie der Künste, Berlin, and by the authors All rights reserved by Wolke Verlag, Hofheim Printed in Germany Editorial assistance: Lynn Matheson, Anouk Jeschke, Alexander K. Rothe Music examples set by Oliver Dahin, Berlin Scans: Kerstin Brümmer Typeset in Simoncini Garamond by michon, Hofheim Print: AK-Druck&Medien GmbH, Schneckenlohe Cover design: Friedwalt Donner, Alonissos Cover photo: Misha Donat, London ISBN 978-3-936000-28-3 Contents Werner Grünzweig: In Dialogue with the Past . 7 Paul Griffiths: “…es ist nicht wie es war…”. The Music of Alexander Goehr . 15 Alexander Goehr: Learning to Compose . 97 Catalogue of the Music Manuscripts in the Alexander Goehr Archive . 127 CD-Supplement . 151 Werner Grünzweig In Dialogue with the Past The name Goehr has been familiar in music circles in central Europe for decades. Alexander Goehr’s father, Walter Goehr (1903-60), a former member of Arnold Schoenberg’s master class at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, was known not only for his productions of Claudio Monteverdi’s Vespers and operas but also for his performances of contemporary music. Compositions by Alexander Goehr, who has been called “Sandy” since childhood days, have been featured at renowned music festivals in Germany since the mid-1950s. In 1956 his Fantasia, Op. 4, was performed at the Darmstadt Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in a pro- gramme also including works by Ernst Krenek, Arnold Schoenberg, Luigi Nono and Bernd Alois Zimmermann. -

Perspectives on Harmony and Timbre in the Music of Olivier Messiaen, Tristan Murail, and Kaija Saariaho

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2019 Liminal aesthetics : perspectives on harmony and timbre in the music of Olivier Messiaen, Tristan Murail, and Kaija Saariaho. Jackson Harmeyer University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Harmeyer, Jackson, "Liminal aesthetics : perspectives on harmony and timbre in the music of Olivier Messiaen, Tristan Murail, and Kaija Saariaho." (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3177. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3177 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL AESTHETICS: PERSPECTIVES ON HARMONY AND TIMBRE IN THE MUSIC OF OLIVIER MESSIAEN, TRISTAN MURAIL, AND KAIJA SAARIAHO By Jackson Harmeyer B.A., Louisiana Scholars’ College, 2013 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Music of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in Music History and Literature Department of Music History and Literature University of -

Britten in Beijing

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited February 2013 2013/1 Reich Radio Rewrite Britten in Beijing Steve Reich’s new ensemble work, with first performances in Included in this issue: The Britten centenary sees the composer’s drawings, resulting in a spectacular series of the UK and US in March, draws inspiration from songs by music celebrated worldwide including many animal lanterns handcrafted in Shangdong van der Aa Radiohead. works receiving territorial premieres, from Province. The production used the biblical Interview about his new 3D song through to reworkings by Stravinsky. South America to Asia and the Antipodes. tale of Noah to explore contemporary film opera Sunken Garden “It was not my intention to make anything like As an upbeat to this year’s events, the first ecological concerns. Through a series of ‘variations’ on these songs, but rather to Britten opera was staged in China with a educational projects, Noye’s Fludde provided draw on their harmonies and sometimes Noye’s Fludde collaboration between an illustration of man’s struggle with the melodic fragments and work them into my Northern Ireland Opera, the KT Wong environment and the significance of flood own piece. As to actually hearing the original Foundation and the Beijing Music Festival. mythology to both Chinese and Western cultures. songs, the truth is – sometimes you hear First staged in Belfast Zoo last summer as them and sometimes you don’t.” part of the Cultural Olympiad, Oliver Mears’s Overseas Britten highlights in 2013 include Photo: Wonge Bergmann Reich encountered the music of Radiohead production transferred in October to Beijing as territorial opera premieres in Brazil, Chile, following a performance by Jonny part of the UK Now Festival. -

2017-18 Season Brochure with Links

2017-2018 SEASON 2017-2018 SEPTEMBER 2017 – JULY 2018 SEPTEMBER 2017 – JULY Director: John Gilhooly OBE, HonRAM, HonFGS, HonRCM, HonFRIAM 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP www.wigmore-hall.org.uk Box Office Tel: 020 7935 2141 The Wigmore Hall Trust, Registered Charity Number 1024838 2017/18 Season September 2017 – July 2018 Design and print www.graphicimpressions.co.uk 2 • Welcome to our new look Wigmore Hall Season Brochure. I hope that you find it informative, clear and easy to use. Our season will include residencies from, amongst others, Isabelle Faust, Christian Tetzlaff, Sir András Schiff, Jörg Widmann and Sonia Prina. The season will include a 17-concert survey of Haydn’s string quartets with all of Haydn’s quartets from the Op. 20s onwards, and Cuarteto Casals will present a complete cycle of Beethoven’s string quartets, alongside new works by living composers. Vocal highlights include a performance of Winterreise by Mark Padmore and Mitsuko Uchida, and Director’s Roderick Williams’s first performances of Die schöne Mullerin, Winterreise and Schwanengesang, as well as recitals from Ian Bostridge, Sarah Connolly, Joyce Introduction DiDonato, Christian Gerhaher, Philippe Jaroussky and Simon Keenlyside. The Nash Ensemble will dedicate its 2017/18 Season to an exploration of French chamber music, performing repertoire by Debussy, Ravel, Faure and Poulenc. Other chamber concerts include appearances by Renaud Capuçon, Julia Fischer Quartet, Quatuor Ebène, the Takács Quartet, Alisa Weilerstein, Leila Josefowicz, and a performance by Leonidas Kavakos and Yuja Wang. The London Pianoforte Series includes performances from Francesco Piemontesi, who will continue his Mozart piano sonata cycle; Nelson Freire, who will mark the 50th anniversary of his Wigmore Hall debut with a recital on the exact day on 17 February 2018; and Daniil Trifonov with Rachmaninov and Chopin, as well as recitals from Jonathan Biss, Imogen Cooper, Bertrand Chamayou, Ingrid Fliter, Kirill Gerstein, Ivana Gavrić, Richard Goode, Igor Levit and Steven Osborne. -

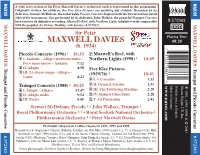

Maxwell Davies’S Orchestral Work Is Represented in This Programme

NAXOS NAXOS A wide cross-section of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies’s orchestral work is represented in this programme. Originally written for children, the Five Klee Pictures are anything but childish. Recorded by its dedicatee, Stewart McIlwham, the remarkable Piccolo Concerto displays both the lyrical and mercurial sides of the instrument. Also performed by its dedicatee, John Wallace, the powerful Trumpet Concerto here receives its definitive recording. Maxwell’s Reel, with Northern Lights inhabits worlds comparable 8.572363 MAXWELL DAVIES: MAXWELL DAVIES: with the popular An Orkney Wedding with Sunrise (8.572352). DDD Sir Peter Playing Time MAXWELL DAVIES 68:28 (b. 1934) 7 Piccolo Concerto (1996) 1 16:33 7 Maxwell’s Reel, with 47313 23637 1 I. Andante – Allegro moderato molto – Northern Lights (1998) 3 10:49 Poco meno mosso – Andante 7:12 Trumpet and Piccolo Concertos Trumpet 2 II. Adagio 4:58 Five Klee Pictures and Piccolo Concertos Trumpet 3 III. Lo stesso tempo – Allegro – (1959/76) 4 10:41 Lento 4:23 8 I. A Crusader 1:35 4 9 www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ Trumpet Concerto (1988) 2 30:25 II. Oriental Garden 1:35 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 4 I. Adagio – Allegro 13:47 0 III. The Twittering Machine 2:20 1991, 1995, 1998 & 5 II. Adagio molto 9:54 ! IV. Stained-Glass Saint 2:28 6 III. Presto 6:45 @ V. Ad Parnassum 2:43 Stewart McIlwham, Piccolo 1 • John Wallace, Trumpet 2 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 1, 3 • Royal Scottish National Orchestra 2 Philharmonia Orchestra 4 • Peter Maxwell Davies Ꭿ Previously released on Collins Classics in 1991, 1995 and 1998 2013 Recorded at St Augustine's Church, Kilburn, London, on 18th May, 1998 (tracks 1-3, 7); at Glasgow City Hall, Scotland, in April 1990 (tracks 4-6), and at All Saints Church, Tooting, London, on 3rd December, 1994 8.572363 8.572363 (tracks 8-12) • Producer: Veronica Slater • Engineer: John Timperley (tracks 1-3, 7-12); David Flower (tracks 4-6) Publishers: Chester Music Ltd. -

Developing Musical Talent

Corporate Responsibility Update DEVELOPING MUSICAL TALENT For more information see bbc.co.uk/outreach RECOGNISING THE SCOPE AND SCALE OF MUSIC ON THE BBC “The BBC must be the risk capital for the UK’s creative industries. The Space for the Arts. The wonderful BBC Films. And I want the same in music. The BBC broadcasts a huge amount of music across radio and television. But I want us to be recognised for what we do – for BBC Music to be a brand that stands proudly alongside BBC News or BBC Sport.” Tony Hall Director-General 2 DEVELOPING MUSICAL TALENT The BBC has always But these events and initiatives From stimulating creativity been an advocate and are about much more than to representing communities, supporter of music and producing programmes for promoting education and musical talent. consumption on television, radio learning to sustaining citizenship, and online. and helping our audiences From the BBC Proms to They go beyond broadcasting benefit from emerging the BBC Young Musician, the and they go a considerable way communications technology Glastonbury Festival to BBC towards helping us meet our and services, we will continue Cardiff Singer of the World, Public Purposes. They also play to support, develop and help the BBC Radio 2 Chorister of a vital role in fostering a vibrant nurture new talent across the Year to The Voice, and BBC creative future for the UK, with all music genres. And we will Introducing to some of Britain’s the BBC taking a leading role maintain a long tradition of finest and most hard-working in the development of the arts showcasing British talent to the orchestras, music is in our DNA and the celebration of British world. -

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES an Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise

PETER MAXWELL DAVIES An Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ben Gernon Sean Shibe guitar Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ben Gernon conductor Sean Shibe guitar Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016) 1. Concert Overture: Ebb Of Winter ..................................................... 17:41 Hill Runes* 2. Adagio – Allegro moderato ................................................................ 1:58 3. Allegro (with several changes of tempo) ........................................ 0:50 4. Vivace scherzando ............................................................................... 0:48 5. Adagio molto .......................................................................................... 2:27 6. Allegro (dying away into ‘endless’ silence) ..................................... 1:55 7. Last Door Of Light ............................................................................... 16:38 8. Farewell To Stromness* ...................................................................... 4:26 9. An Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise ................................................. 12:34 Total Running Time: 59 minutes *solo guitar Recorded at Usher Hall, Edinburgh, UK 14–16 September 2015 Produced by John Fraser (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise, Ebb of Winter, Last Door of Light) and Philip Hobbs (Farewell to Stromness and Hill Runes) Recorded by Calum Malcolm (An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise, Ebb of Winter, Last Door of Light) and Philip Hobbs (Farewell to Stromness and Hill Runes) Post-production by Julia Thomas Cover image by