20Th Century Book Inside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

Macmillan History 9

Chapter 5 Making a nation HISTORY SKILLS In this chapter you will learn to apply the following historical skills: • explain the effects of contact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, categorising these effects as either intended or unintended • outline the migration of Chinese to the goldfields in Australia in the 19th century and attitudes towards the Chinese, as revealed in cartoons • identify the main features of housing, sanitation, transport, education and industry that influenced living and working conditions in Australia • describe the impact of the gold rushes (hinterland) on the development of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ • explain the factors that contributed to federation and the development of democracy in Australia, including defence concerns, the 1890s depression, nationalist ideals, egalitarianism and the Westminster system • investigate how the major social legislation of the new federal government—for example, invalid and old-age pensions and the maternity allowance scheme—affected living and working conditions in Australia. © Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority 2012 Federation celebrations in Centennial Park, Sydney, 1 January 1901 Inquiry questions 1 What were the effects of contact between European 4 What were the key events and ideas in the settlers in Australia and Aboriginal and Torres Strait development of Australian self-government and IslanderSAMPLE peoples when settlement extended? democracy? 2 What were the experiences of non-Europeans in 5 What significant legislation was passed in the Australia prior to the 1900s? period 1901–1914? 3 What were the living and working conditions in Australia around 1900? Introduction THE EXPERIENCE OF indigenous peoples, Europeans and non-Europeans in 19th-century Australia were very different. -

Spring/Summer 2016

News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein Spring/Summer 2016 High-brow, Low-brow, All-brow Bernstein, Gershwin, Ellington, and the Richness of American Music © VICTOR © VICTOR KRAFT by Michael Barrett uch of my professional life has been spent on convincing music lovers Mthat categorizing music as “classical” or “popular” is a fool’s errand. I’m not surprised that people s t i l l c l i n g t o t h e s e d i v i s i o n s . S o m e w h o love classical masterpieces may need to feel reassured by their sophistication, looking down on popular culture as dis- posable and inferior. Meanwhile, pop music fans can dismiss classical music lovers as elitist snobs, out of touch with reality and hopelessly “square.” Fortunately, music isn’t so black and white, and such classifications, especially of new music, are becoming ever more anachronistic. With the benefit of time, much of our country’s greatest music, once thought to be merely “popular,” is now taking its rightful place in the category of “American Classics.” I was educated in an environment that was dismissive of much of our great American music. Wanting to be regarded as a “serious” musician, I found myself going along with the thinking of the times, propagated by our most rigid conservatory student in the 1970’s, I grew work that studiously avoided melody or key academic composers and scholars of up convinced that Aaron Copland was a signature. the 1950’s -1970’s. These wise men (and “Pops” composer, useful for light story This was the environment in American yes, they were all men) had constructed ballets, but not much else. -

Elements of Traditional Folk Music and Serialism in the Piano Music of Cornel Țăranu

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of 12-2013 ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU Cristina Vlad University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Commons Vlad, Cristina, "ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU" (2013). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 65. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU by Cristina Ana Vlad A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Mark Clinton Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2013 ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL FOLK MUSIC AND SERIALISM IN THE PIANO MUSIC OF CORNEL ȚĂRANU Cristina Ana Vlad, DMA University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Mark Clinton The socio-political environment in the aftermath of World War II has greatly influenced Romanian music. During the Communist era, the government imposed regulations on musical composition dictating that music should be accessible to all members of society. -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL How to cite: ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL (2021) English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13924/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush’s ‘Workers’ Music’ on 20 th Century Britain’s Left-Wing Music Scene Alice Robinson Abstract Workers’ music: songs to fight injustice, inequality and establish the rights of the working classes. This was a new, radical genre of music which communist composer, Alan Bush, envisioned in 1930s Britain. -

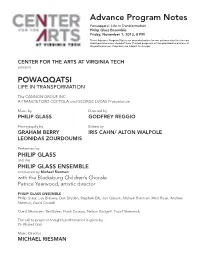

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

Euromac 9 Extended Abstract Template

9th EUROPEAN MUSIC ANALYSIS CONFERENC E — E U R O M A C 9 Hei Yeung Lai The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong [email protected] Goehr’s Piano Sonata through a Transformational Lens the introductory theme also acts as a germ that ‘contains a latent set of ABSTRACT relationships that the themes unfold’, which is depicted by some isographic transformational networks. Background On the other hand, the endings of each section of the Sonata feature different tetrachordal presentations. Specifically, the (013) trichord is Alexander Goehr’s interest in serialism has its root in the embedded in all of these structural tetrachords, which further asserts twelve-note compositional trend in the post-war environment and his the importance of this abstract intervallic motive at the structural level. particular family and cultural background. His Piano Sonata is his first The application of the Klumpenhouwer networks relates these composition to have secured a performance in an international context, structural harmonies by means of isographic networks, which binds the one that de facto launched his professional career. Apart from being chronological structural closures into a complex of relationships and inspired by the rhythmic characteristics of Bartók and Messiaen, Goehr hence reveals the ‘deep structure’ of the Sonata. points out that Liszt’s Piano Sonata and Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony also informed his Sonata, ‘which contained [his] first Implications experiment in the combination of twelve-note row and modal harmony’ The application of transformational analysis, along with that of (Goehr and Wintle 1992, 168-169). The subtitle ‘in memory of Serge Klumpenhouwer net, on Goehr’s Sonata, a novel approach conducted Prokofiev’ in the published scores and the melodic reference to here for the first time, reveals an intricate array of functional Prokofiev’s Seventh Piano Sonata also confirm Goehr’s reference to the relationships among different themes and structural entities, which Russian composer (Rupprecht 2015, 124). -

David Justin CV 2014 Pennsylvania Ballet

David Justin 4603 Charles Ave Austin TX 787846 Tel: 512-576-2609 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.davidjustin.net CURRICULUM VITAE ACADEMIC EDUCATION • University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, Master of Arts in Dance in Education and the Community, May 2000. Thesis: Exploring the collaboration of imagination, creativity, technique and people across art forms, Advisor: Tansin Benn • Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, Edward Kemp, Artistic Director, London, United Kingdom, 2003. Certificate, 285 hours training, ‘Acting Shakespeare.’ • International Dance Course for Professional Choreographers and Composers, Robert Cohen, Director, Bretton College, United Kingdom, 1996, full scholarship DANCE EDUCATION • School of American Ballet, 1987, full scholarship • San Francisco Ballet School, 1986, full scholarship • Ballet West Summer Program, 1985, full scholarship • Dallas Metropolitan Ballet School, 1975 – 1985, full scholarship PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Choreographer, 1991 to present See full list of choreographic works beginning on page 6. Artistic Director, American Repertory Ensemble, Founder and Artistic Director, 2005 to present $125,000 annual budget, 21 contract employees, 9 board members11 principal dancers from the major companies in the US, 7 chamber musicians, 16 performances a year. McCullough Theater, Austin, TX; Florence Gould Hall, New York, NY; Demarco Roxy Art House, Edinburgh, Scotland; Montenegrin National Theatre, Podgorica, Montenegro; Miller Outdoor Theatre, Houston, TX, Long Center for the Performing Arts,