Anastasia Bukina, Anna Petrakova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O FULLETÓ SALA PANTALLA.Indd

Me hace especial ilusión presentar por primera vez en España la I am pleased to present the work of Mat Collishaw for the first time in obra de Mat Collishaw, uno de los artistas más significativos en el Spain. panorama internacional. One of the world’s most significant artists, he makes intelligent, Su mirada inteligente, crítica e incisiva nos habla de los temas critical work that addresses universal subject matter, drawing the universales de una manera muy personal que envuelve al visitor into a game of dualisms: beauty and cruelty, poetry and espectador en un juego de dualidades: belleza y crueldad, poética y provocation, light and darkness. provocación, luz y oscuridad. For this exhibition, we have carefully selected works that form a Las obras se han seleccionado cuidadosamente buscando un natural dialogue with the environment in which they are presented. diálogo natural con el entorno en el que se presentan. I would like to thank the Museo Nacional del Prado, Real Jardin Quiero agradecer la colaboración del Museo Nacional del Prado, Botánico and Blain|Southern gallery for their support. el Real Jardín Botánico y la galería Blain|Southern por su apoyo y I hope Dialogues will inspire in its audience the same admiration and aportación al enriquecimiento de nuestro proyecto. respect towards Collishaw’s work that I feel, as well as demonstrating Deseo que Dialogues despierte en el público la misma admiración our commitment to hosting future projects of this kind. y respeto que siento por la obra de Collishaw, y transmitir con ella Ana Vallés nuestra vocación de retorno. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Hermitage Magazine 27 En.Pdf

VIENNA / ART DECO / REMBRANDT / THE LANGOBARDS / DYNASTIC RULE VIENNA ¶ ART DECO ¶ THE LEIDEN COLLECTION ¶ REMBRANDT ¶ issue № 27 (XXVII) THE LANGOBARDS ¶ FURNITURE ¶ BOOKS ¶ DYNASTIC RULE MAGAZINE HERMITAGE The advertising The WORLD . Fragment 6/7 CLOTHING TRUNKS OF THE MUSEUM WARDROBE 10/18 THE INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD OF THE STATE HERMITAGE Game of Bowls 20/29 EXHIBITIONS 30/34 OMAN IN THE HERMITAGE The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. № ГЭ 9154 The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. Henri Matisse. 27 (XXVII) Official partners of the magazine: DECEMBER 2018 HERMITAGE ISSUE № St. Petersburg State University MAGAZINE Tovstonogov Russian State Academic Bolshoi Drama Theatre The Hermitage Museum XXI Century Foundation would like to thank the project “New Holland: Cultural Urbanization”, Aleksandra Rytova (Stella Art Foundation, Moscow) for the attention and friendly support of the magazine. FOUNDER: THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM Special thanks to Svetlana Adaksina, Marina Antipova, Elena Getmanskaya, Alexander Dydykin, Larisa Korabelnikova, Ekaterina Sirakonyan, Vyacheslav Fedorov, Maria Khaltunen, Marina Tsiguleva (The State Hermitage Museum); CHAIRMAN OF THE EDITORIAL BOARD Swetlana Datsenko (The Exhibition Centre “Hermitage Amsterdam”) Mikhail Piotrovsky The project is realized by the means of the grant of the city of St. Petersburg EDITORIAL: AUTHORS Editor-in-Chief Zorina Myskova Executive editor Vladislav Bachurov STAFF OF THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM: Editor of the English version Simon Patterson Mikhail Piotrovsky -

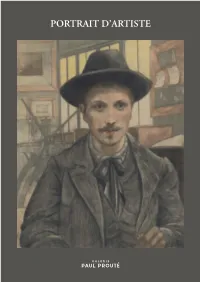

Portrait D'artiste

<--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------><- 15 mm -><--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------> 2020 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 74, rue de Seine — 75006 Paris Tél. — + 33 (0)1 43 26 89 80 e-mail — [email protected] www.galeriepaulproute.com PAUL PROUTÉ GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 1 30/10/2020 16:15:36 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 1920 2020 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 500 ESTAMPES 2020 SOMMAIRE AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................... 7 PRÉFACE ................................................................................ 9 ESTAMPES DES XVIe ET XVIIe SIÈCLES ............................. 15 ESTAMPES DU XVIIIe SIÈCLE ............................................. 61 ESTAMPES DU XIXe SIÈCLE ................................................ 105 ESTAMPES DU XXe SIÈCLE ................................................. 171 INDEX .................................................................................... 202 AVANT-PROPOS près avoir quitté la maison familiale du 12 de la rue de Seine, Paul Prouté s’instal- Alait au 74 de cette même rue le 15 janvier -

José Eloy Hortal Muñoz, Pierre-François Pirlet, and África Espíldora García (Eds), El Ceremonial En La Corte De Bruselas Del Siglo Xvii

Early Modern Low Countries 3 (2019) 2, pp. 306-307 - eISSN: 2543-1587 306 Note José Eloy Hortal Muñoz, Pierre-François Pirlet, and África Espíldora García (eds), El ceremonial en la Corte de Bruselas del siglo xvii. Los manuscritos de Francisco Alonso Lozano, Brussels, Commission Royale d’Histoire, 2018, 271 pp. isbn 978-2-87044-016-2 Since the 1970s, numerous studies have been devoted to the history of the princely courts of Europe. Many of these have focused on the magnificent royal courts of France, England, and Spain, but in recent years the courts of smaller principalities, too, have been researched extensively. By comparison, the court of Brussels has received scant attention in historiography. Owing to its reputation as a subaltern court of the Spanish monarchy, the Brussels court was often considered to have been of secondary importance at best. Most scholars have therefore tended to concen- trate on the first decades of the seventeenth century, when the archdukes Albert and Isa- bella (1598-1633) inhabited the palace on the city’s Coudenberg hill and created a court that rivalled many others in size and opulence. While these studies have greatly contrib- uted to our knowledge of the Brussels court as a centre of international diplomacy and culture, its history during the second half of the seventeenth century has remained largely unexplored. From the 1660s onwards the Coudenberg palace became the residence of a rapid succession of governors, few of whom remained in the Low Countries long enough to take a vested interest in its upkeep. The resulting scholarly indifference towards this later period has also been affected by the problematic archival situation, as relevant sources are scattered across multiple European archives. -

Erwin Und Elmire 1776 (70’)

Sound Reseach of Women Composers: Music of the Classical Period (CP 1) Anna Amalia Herzogin von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach 1739–1807 Erwin und Elmire 1776 (70’) Schauspiel mit Gesang nach einem Text von Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Erstveröffentlichung/First Publication erste vollständige szenische Aufführung am 25. Juni 2009 im Ekhof-Theater Gotha first complete scenic performance on June 25th 2009 at Ekhof-Theatre Gotha hrsg. von /edited by Peter Tregear Aufführungsmaterial leihweise / Performance material available for hire Personen Olympia: Sopran/Soprano Elmire: Sopran/Soprano Bernardo: Tenor oder/or Sopran/Soprano Erwin: Tenor oder/or Sopran/Soprano Orchesterbesetzung/Instrumentation 2 Flöten/2 Flutes 2 Oboen/2 Oboes Fagott/Bassoon 2 Hörner/2 Horns Violine 1/2 Viola Kontrabass Quelle: Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Weimar, Mus II a:98 (Partitur), Mus II c:1 (Vokalstimmen) © 2011 Furore Verlag, Naumburger Str. 40, D-34127 Kassel, www.furore-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten / Das widerrechtliche Kopieren von Noten wird privat- und strafrechtlich geahndet Printed in Germany / All rights reserved / Any unauthorized reproduction is prohibited by law Dieses Werk ist als Erstveröffentlichung nach §71 UrhG urheberrechtlich geschützt. Alle Aufführungen sind genehmigungs- und gebührenpflichtig. Furore Edition 2568 • ISMN: 979-0-50182-383-5 Inhalt/Contents Seite / Page Dr. Peter Tregear Erwin und Elmire – Eine Einführung 3 Professor Nicolas Boyle Goethes Erwin und Elmire in seiner Zeit 4 Dr. Lorraine Byrne Bodley Die Tücken des Musiktheaters: Anna Amalias -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

North of Perth

A LONG ROAD HOME The Life and Times of Grisha Sklovsky 1915-1995 by John Nicholson This book is dedicated to the memory of Chaja, also known as Anna Sklovsky, who placed her trust in justice and the rule of law and was betrayed by justice and the rule of law in a gas-chamber at Auschwitz. 2 CONTENTS Preface Introduction Chapter One Siberia Chapter Two Berlin Chapter Three Lyon Chapter Four The Czech Brigade Chapter Five England Chapter Six Waiting Chapter Seven Invasion Chapter Eight From Greece to Paris to America Chapter Nine Melbourne Chapter Ten Family, Friends and Europe Chapter Eleven Battlegrounds and the Antarctic Chapter Twelve New Directions and Multiculturalism Chapter Thirteen SBS Television Chapter Fourteen Of Camberwell and other battles Chapter Fifteen Moscow Chapter Sixteen Last Days Epilogue Notes Index 3 Introduction In the early years of the twentieth century, when the word pogrom [Russian: devastation] had entered the world‟s vocabulary, many members of a Russian Jewish family named Sklovsky were leaving their long-time homes within the Pale of Settlement.1 They were compelled to leave because, after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, experiments in half-hearted liberalism were abandoned and throughout the regimes of Alexander III [1881-1894] and Nicholas II [1894-1917] the Jews of Russia were subjected to endless persecution. As a result of the partitions of Poland in the eighteenth century more than a million Jews had found themselves within the Russian empire but permitted to live only within the Pale, the boundaries of which were determined in 1812. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Northern Italianate Landscape Painters

Northern Italianate Landscape Painters ... Northern artists had long spent time in Italy – hence the work of Pieter de Kempeneer (1503-1580) (Room 9) and Frans Floris (1516-1570) in the sixteenth century, who drew their inspiration from the Antique and contemporary masters. Landscape painters Paul Bril (1554-1626) and Adam Elsheimer (1574/78-1610/20) (Room 10), settled there from the end of the sixteenth century and were to influence the Italian school profoundly. However, from around 1620, the Northern Diaspora gave rise to a novel way of representing the towns and countryside of Italy. Cornelis van Poelenburgh (1595/96-1667) went to Rome in 1617 and around 1623 was among the founder members of the Bentvueghels “birds of a feather”, an association of mutual support for Northern artists, goldsmiths and “art lovers” – not only Flemish and Dutch, but Room also Germans and even a few French. He painted shepherds in the ruins and plains of Latium where the harsh light creates strong shadows. Around 1625, the Dutch painter Pieter van Berchem Laer (1599-1642 ?), nicknamed Il Bamboccio, invented the bambocciate, a different take on Caravaggesque scenes of realism showing moments of contemporary Italian low-life in ... the open air and bringing a modern feel to the subject matter. The bambocciate met with considerable success. Flemish and From these two trends – pastoral landscapes suffused with light, and racy at times Dutch Painting vulgar scenes of daily life – was to develop a whole chapter in European painting, dominated by Northern artists but also marked by Italians such as Michelangelo Cerquozzi (1602-1660) and French painters like Sébastien Bourdon (1616-1671). -

Der Weltgeist Von Weimar Das Wissen Die Literatur Bescherte Der Stadt Inneren Reichtum, Konnte Aber Äußere Katastrophen Nicht Verhindern Der Zeit

Raritäten Die Herzogin Die Bibliothek besitzt SONDERAUSGABE Auf Anna Amalias kostbare Handschriften, Spuren durch Weimar Bibeln und Globen S.8/9 Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek spazieren S.19 WWW.WELT.DE OKTOBER 2007 EDITORIAL Der Weltgeist von Weimar Das Wissen Die Literatur bescherte der Stadt inneren Reichtum, konnte aber äußere Katastrophen nicht verhindern der Zeit Am 2. September 2004 brannten Teile T Von Dieter Stolte der Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in Weimar aus. Rund 50 000 Bücher ibliotheken sind das Wissen wurden zerstört. Drei Jahre dauerten der Zeit. Ihre Geschichte die Wiederaufbauarbeiten. Am 24. Ok- begann im 1. Jahrtausend tober 2007 kann das historische Bvor Christus, als der Assyrer- Bibliotheksgebäude mit dem restau- könig Assurbanipal in Ninive rierten Rokokosaal eröffnet werden. 5000 Keilschrifttafeln zusammen- trug. Sie überlebten den Zusam- T Von Wolf Lepenies menbruch seines Reiches und können noch heute im Britischen nna Amalia, Herzogin von Museum studiert werden. So Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, erging es vielen Bibliotheken des starb am 10. April 1807. In Altertums: Trotz Naturkatastro- Weimar hielt zu ihrem „fei- phen, Feuersbrünsten und Plün- erlichsten Andenken“ Goe- derungen überlebten sie, blieben Athe die Ansprache. Er erinnerte Zeugnisse der Menschheit. Ins- an die Fürstin als eine große Frau, besondere die Klöster erwarben die dem „übrigen Menschenge- sich große Verdienste bei der schlecht“ ein Beispiel für „Stand- Pflege von Bibliotheken. Die Höfe haftigkeit im Unglück und teil- der Fürsten machten sie im 17. nehmendes Wirken im Glück“ ge- und 18. Jahrhundert zum Mittel- geben hatte. punkt geistiger Begegnungen. Wo Standhaftigkeit benötigte Anna es Bibliotheken gab, wehte als- Amalia vor allem im Siebenjähri- bald ein Geist des Wissens und gen Krieg (1756–1763): Die Staats- Verstehens.