David Van Der Linden, Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Calvin Bibliography

2012 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul W. Fields and Andrew M. McGinnis (Research Assistant) I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural Context—Intellectual History C. Cultural Context—Social History D. Friends E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin’s Works A. Works and Selections B. Criticism and Interpretation III. Calvin’s Theology A. Overview B. Revelation 1. Scripture 2. Exegesis and Hermeneutics C. Doctrine of God 1. Overview 2. Creation 3. Knowledge of God 4. Providence 5. Trinity D. Doctrine of Christ E. Doctrine of the Holy Spirit F. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Overview 2. Covenant 3. Ethics 4. Free Will 5. Grace 6. Image of God 7. Natural Law 8. Sin G. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Assurance 2. Atonement 1 3. Faith 4. Justification 5. Predestination 6. Sanctification 7. Union with Christ H. Doctrine of the Christian Life 1. Overview 2. Piety 3. Prayer I. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline 3. Instruction 4. Judaism 5. Missions 6. Polity J. Worship 1. Overview 2. Images 3. Liturgy 4. Music 5. Preaching 6. Sacraments IV. Calvin and Social-Ethical Issues V. Calvin and Economic and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Overview 2. Christian Life 3. Church Discipline 4. Ecclesiology 5. Holy Spirit 6. Predestination 7. Salvation 8. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Arts 2. Cultural Context—Intellectual History 2 3. Cultural Context—Social History 4. Education 5. Literature C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. Australia 2. Eastern Europe 3. England 4. Europe 5. France 6. Geneva 7. Germany 8. Hungary 9. India 10. -

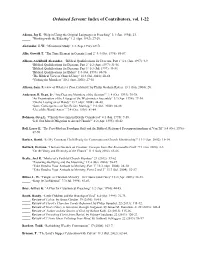

Ordained Servant: Index of Contributors, Vol. 1-22

Ordained Servant: Index of Contributors, vol. 1-22 Adams, Jay E. “Help in Using the Original Languages in Preaching” 3:1 (Jan. 1994): 23. _____. “Working with the Eldership” 1:2 (Apr. 1992): 27-29. Alexander, J. W. “Ministerial Study” 1:3 (Sep. 1992): 69-71. Allis, Oswald T. “The Time Element in Genesis 1 and 2” 4:4 (Oct. 1995): 85-87. Allison, Archibald Alexander. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 1” 6:1 (Jan. 1997): 4-9. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 2” 6:2 (Apr. 1997): 31-36. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 3” 6:3 (Jul. 1997): 49-54. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Elders” 3:4 (Oct. 1994): 80-96. _____. “The Biblical View of Church Unity” 10:3 (Jul. 2001): 60-64. _____. “Visiting the Members” 10:2 (Apr. 2001): 27-30. Allison, Sam. Review of What is a True Calvinist? by Philip Graham Ryken. 13:1 (Jan. 2004): 20. Anderson, R. Dean, Jr. “Are Deacons Members of the Session?” 2: 4 (Oct. 1993): 75-78. _____. “An Examination of the Liturgy of the Westminster Assembly” 3:2 (Apr. 1994): 27-34. _____. “On the Laying on of Hands” 13:2 (Apr. 2004): 44-48. _____. “Some Consequences of Sex Before Marriage” 9:4 (Oct. 2000): 86-88. _____. “Use of the Word ‘Amen’” 7:4 (Oct. 1998): 81-84. Bahnsen, Greg L. “Church Government Briefly Considered” 4:1 (Jan. 1995): 9-10. _____. “Is It Our Moral Obligation to Attend Church?” 4:2 (Apr. 1995): 40-42. Ball, Larry E. “The Post-Modern Paradigm Shift and the Biblical, Reformed Presuppositionalism of Van Til” 5:4 (Oct. -

Theology of the Westminster Confession, the Larger Catechism, and The

or centuries, countless Christians have turned to the Westminster Standards for insights into the Christian faith. These renowned documents—first published in the middle of the 17th century—are widely regarded as some of the most beautifully written summaries of the F STANDARDS WESTMINSTER Bible’s teaching ever produced. Church historian John Fesko walks readers through the background and T he theology of the Westminster Confession, the Larger Catechism, and the THEOLOGY The Shorter Catechism, helpfully situating them within their original context. HISTORICAL Organized according to the major categories of systematic theology, this book utilizes quotations from other key works from the same time period CONTEXT to shed light on the history and significance of these influential documents. THEOLOGY & THEOLOGICAL of the INSIGHTS “I picked up this book expecting to find a resource to be consulted, but of the found myself reading the whole work through with rapt attention. There is gold in these hills!” MICHAEL HORTON, J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary California; author, Calvin on the Christian Life WESTMINSTER “This book is a sourcebook par excellence. Fesko helps us understand the Westminster Confession and catechisms not only in their theological context, but also in their relevance for today.” HERMAN SELDERHUIS, Professor of Church History, Theological University of Apeldoorn; FESKO STANDARDS Director, Refo500, The Netherlands “This is an essential volume. It will be a standard work for decades to come.” JAMES M. RENIHAN, Dean and Professor of Historical Theology, Institute of Reformed Baptist Studies J. V. FESKO (PhD, University of Aberdeen) is academic dean and professor of systematic and historical theology at Westminster Seminary California. -

Calvinism and Religious Toleration in France and The

CALVINISM AND RELIGIOUS TOLERATION IN FRANCE AND THE NETHERLANDS, 1555-1609 by David L. Robinson Bachelor of Arts, Memorial University of Newfoundland (Sir Wilfred Grenfell College), 2011 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Examining Board: Cheryl Fury, PhD, History, UNBSJ Sean Kennedy, PhD, Chair, History Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Joanne Wright, PhD, Political Science This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK May, 2011 ©David L. Robinson, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91828-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91828-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Conflict and the Making of Religious Cultures in Sixteenth-Century France

Conflict and the Making of Religious Cultures in Sixteenth-Century France Howard G. Brown Binghamton University, SUNY In 1973, Natalie Zemon Davis published what has become the most influential article on the wars of religion: “The Rites of Violence: Religious Riot in Sixteenth-Century France.” The impact of this article reached well beyond specialists in the field to become a pioneering model of cultural history. At the time of its publication, most historians were laboring in the vineyards of social history, trampling out the grapes of class conflict. This was equally true of sixteenth- century specialists whose arduous plodding up and down in tax rolls and judicial records seemed to yield a robust vintage of bourgeois-led religious movements (in the loose sixteenth-century sense of urban, middling groups ranging from master artisans to municipal magistrates). In France, at least, the socio-economic status and ambitions of these men made them useful allies in aristocratic struggles over control of the French monarchy, debilitated by the bizarre death of Henri II in 1559. In this way, class struggle apparently helped both to complement and complicate existing explanations that emphasized either religion or politics as the dominant forces in a series of civil wars that devastated France from 1562 to 1598. Davis’ article was hugely successful because it sweepingly replaced class conflict with what can only be described as cultural conflict, though she did not use the term.1 Her article discredited supposed causal connections between grain prices and popular riots using religious rhetoric and persuasively suggested that Protestant victims and Catholic perpetrators represented more or less proportionately the full range of urban identities except for unskilled workers. -

Barbara B. Diefendorf Nicholas Terpstra Boston University University of Toronto

Habent sua fata libelli Early Modern Studies Series General Editor Michael Wolfe Queens College, CUNY Editorial Board of Early Modern Studies Elaine Beilin Raymond A. Mentzer Framingham State College University of Iowa Christopher Celenza Robert V. Schnucker Johns Hopkins University Truman State University, Emeritus Barbara B. Diefendorf Nicholas Terpstra Boston University University of Toronto Paula Findlen Margo Todd Stanford University University of Pennsylvania Scott H. Hendrix James Tracy Princeton Theological Seminary University of Minnesota Jane Campbell Hutchison Merry Wiesner- Hanks University of Wisconsin– Madison University of Wisconsin– Milwaukee Mary B. McKinley University of Virginia SocialRelations-Diefendorf.indb 2 7/1/16 1:22 PM Early Modern Studies 19 Truman State University Press Kirksville, Missouri SocialRelations-Diefendorf.indb 3 7/1/16 1:22 PM Copyright © 2016 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover art: Philippe de Champaigne (1602– 1674), Le Prévôt des marchands et les échevins de la ville de Paris. Oil on canvas, 1648. Louvre Museum, Paris, Legs du Dr Louis La Caze, 1869. Cover design: Lisa Ahrens Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Diefendorf, Barbara B., 1946- editor of compilation. | Descimon, Robert, honouree. Title: Social relations, politics, and power in early modern France : Robert Descimon and the historian’s craft / edited by Barbara B. Diefendorf. Description: Kirksville, Missouri : Truman State University Press, [2016] | Series: Early modern studies ; 19 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016009565 (print) | LCCN 2016029104 (ebook) | ISBN 9781612481630 (library binding : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9781612481647 Subjects: LCSH: France—History—16th century—Historiography. | France—History—17th century—Historiography. -

Social Context for Religious Violence in the French Massacres of 1572

Social Context for Religious Violence in the French Massacres of 1572 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities By SHANNON LEE SPEIGHT B.A., University of Texas at Arlington, 2005 2010 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES July 8, 2010 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Shannon Lee Speight ENTITLED Social Context for Religious Violence in the French Massacres of 1572 BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Humanities, ____________________________________ Kirsten Halling, Ph.D. Co-Thesis Director ____________________________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. Co-Thesis Director ____________________________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. Director, Master of Humanities Program Committee on Final Examination _______________________________ Kirsten Halling, Ph.D. Committee Member _______________________________ Ava Chamberlain, Ph.D. Committee Member ________________________________ Marie Hertzler, Ph.D. Committee Member ___________________ Andrew Hsu, PhD. Dean, School of Graduate Studies ABSTRACT Speight, Shannon Lee. M.HUM, Department of Humanities, Wright State University, 2010. Social Context for Religious Violence in the French Massacres of 1572 The project looks at violence as a social norm during the French massacres of 1572, causing widespread violence at a popular level, at the heart of which was religious group identity. The work examines outbreaks of fighting between Catholics and Huguenots starting in Paris with the St. Bartholomew‟s Day Massacre and spreading to provincial cities in the following months. Rather than viewing hostility as instigated from the top levels of society, this works aims to verify that there existed within France an acceptance of aggression that, encouraged by inflammatory religious rhetoric, resulted in the popular violence of the massacres. -

Of Religion Really Wars of Religion?

Book Chapter Were the French Wars of Religion Really Wars of Religion? BENEDICT, Philip Joseph Reference BENEDICT, Philip Joseph. Were the French Wars of Religion Really Wars of Religion? In: Palaver, W. ; Rudolph, H. & Regensburger, D. The European wars of religion. Farnham : Ashgate, 2016. Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:97321 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 4t;/y / / The European Wars of Religion An Interdisciplinary Reassessment ofSources, Interpretations, and l\1yths Edited by WOLFGANG PALAVER University ofInnsbruck, Austria HARRIET RUDOLPH University ofRegensburg, Germany DIETMAR REGENSBURGER University ofInnsbruck, Austria ASHGATE UNIVERSITÉ DE . GENÈVE ~ Institut d'Histoire •\. ·de-·----- le Réformation--- ----- <P Chapter 3 Were the French Wars of Religion Really Wars ofReligion? 1 Philip Benedict Even to ask the question posed in the title of this essay might seem unnecessary, since no ether conflict in lace medieval or early modern history indudes the phrase 'wars of religion' in the label conventionally affixed tait. In fact, however, historians from the sixteenth century to the present day have debated whether the civil wars chat roiled France from c.l560 to 1598 arose primarily from religious differences or aristocratie ambition. Consider chese two) quotations from the years 1579-81, the first from a Catholic historian and the second from a Protestant: Those who have considered things closely have known that neicher religion alone nor the oppression of the Protestants caused the kingdom's troubles, but also the hacreds that eldsted among che great nobles because of their ambitions and rivalries. 2 Those who, in speaking generally of the truc sources of the strange tumults that our fachers began but have not yet finished, attribuee the source only co the difference in religion, are immediacely contradicted by chose most clairvoyant in affairs of stace, who find only human passions . -

Religious Violence, Certainty, and Doubt in the French Wars of Religion

Que sais-je? Religious Violence, Certainty, and Doubt in the French Wars of Religion Mack P. Holt George Mason University Most of the religious violence resulting from the religious reformations of the sixteenth century shared much in common with the religious violence of the medieval period that preceded it. It was largely sanctioned by secular and/or ecclesiastical authority. It tended to break out in places where new religious ideas threatened to subvert established ways of navigating the boundaries between the visible world and the invisible world. And it also tended to invoke the certainty of knowing that unorthodox religious ideas and practices, if allowed to go unchallenged, threatened both Christian society in the visible world and eternal salvation in the invisible world. Having said that, however, I also wish to argue for both historicity and specificity in trying to analyze religious violence. It is hardly something monolithic, universal, and inevitable as critics of organized religion are sometimes eager to suggest. Religious violence has to be understood in the social and cultural contexts that produced it. Indeed, one of the most intriguing questions for scholars of the Reformation generally, and the French reformation in particular, is why violence among civilians— neighbors killing neighbors—escalated significantly in the sixteenth century. How do we explain, for example, the scale of popular violence that erupted in Paris and a dozen provincial cities in France in August 1572, known collectively as the St. Bartholomew’s massacres, when maybe 2,000 Huguenots in the capital and another 4,000 in the provinces were murdered? 1 The most convincing explanation is the classic thesis offered by Natalie Zemon Davis more than thirty years ago. -

PHILIP BENEDICT BORN August 20, 1949, Washington, D.C. ADDRESS: Avenue De Champel 23, 1206 Genève, Suisse/Switzerland TELEPHONE

PHILIP BENEDICT CURRICULUM VITAE BORN August 20, 1949, Washington, D.C. CITIZENSHIP: U.S.A. ADDRESS: Avenue de Champel 23, 1206 Genève, Suisse/Switzerland TELEPHONE: +41 (0)22 346 91 22 EDUCATION Date Degree(s) and Field Institution 1966-70 B.A. summa cum laude in History Cornell University with distinction in all subjects 1970-75 M.A., History, 1972 Princeton University Ph.D., History, 1975 PERMANENT ACADEMIC POSITIONS Date Position Institution 1976-1978 Assistant Professor of History University of Maryland, College Park 1978-2005 Assistant Professor of History to William Brown University Prescott and Annie McClelland Smith Professor of History and Religion 2005- Professeur ordinaire (2005-2014), Institut d'histoire de la directeur (2006-2009), and currently Réformation, Université de Profeseur honoraire (i.e. emeritus) Genève SHORT-TERM ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 1975-1976 Visiting Assistant Professor Cornell University 1983-1984 Member Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton 1986, 2002 Directeur d'études associé Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris May 1999 Directeur d'études associé Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Ve Section, Paris 2001-2002 Visiting Fellow All Souls College, Oxford January 2003 Professeur invité Université de Lyon II Benedict c.v.—version of 3/5/2015 10:49:00 AM 2 Fall 2004 Frese Senior Research Fellow Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Washington March 2010 Gastdozent Humboldt Universität zu Berlin March 2014 Professeur invité chaire Alphonse Dupront Université de Paris IV- Sorbonne RESEARCH IN PROGRESS 1.) Large-scale account of the critical years of the French Reformation from the foundation of Reformed churches in 1555 through the First Civil War (1562-63). -

PHILIP BENEDICT Institut D'histoire De La Réformation Avenue De Champel 23 Université De

PHILIP BENEDICT CURRICULUM VITAE Institut d'histoire de la Réformation Avenue de Champel 23 Université de Genève 1206 Genève 1211 Genève Suisse/Switzerland Suisse/Switzerland +41 (0)22 346 91 22 +41 (0)22 379 71 40 fax +41 (0)22 379 71 33 EDUCATION Date Degree(s) and Field Institution 1966-70 B.A. summa cum laude in History Cornell University with distinction in all subjects 1970-75 M.A., History, 1972 Princeton University Ph.D., History, 1975 PERMANENT ACADEMIC POSITIONS Date Position Institution 1976-78 Assistant Professor of History University of Maryland, College Park 1978-2005 Assistant Professor of History to William Brown University Prescott and Annie McClelland Smith Professor of History and Religion 2005- Professeur ordinaire (2005- ) et Institut d'histoire de la directeur (2006-2009) Réformation, Université de Genève SHORT -TERM ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 1975-76 Visiting Assistant Professor Cornell University 1983-84 Member Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton 1986, 2002 Directeur d'études associé Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris May 1999 Directeur d'études associé Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Ve Section, Paris 2001-02 Visiting Fellow All Souls College, Oxford Benedict c.v.—version of 1/10/2012 9:31:00 AM 2 January 2003 Visiting Professor Université de Lyon II Fall 2004 Frese Senior Research Fellow Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Washington March 2010 Gastdozent Humboldt Universität zu Berlin RESEARCH IN PROGRESS 1.) Large-scale account of the critical years of the French Reformation from the foundation of Reformed churches in 1555 through the First Civil War (1562-63). -

Shaping the Memory of the French Wars of Religion. the First Centuries Philip Benedict in 1683, the Historian Louis Maimbourg D

CHAPTER SIX SHAPING THE MEMORY OF THE FRENCH WARS OF RELIGION. THE FIRST CENTURIES Philip Benedict In 1683, the historian Louis Maimbourg dedicated his Histoire de la Ligue to Louis XIV with some reflections about the past century.1 Although France was now a unified kingdom capable of dictating terms to the entire globe, he wrote, it had almost been destroyed in the sixteenth century by ‘two baneful leagues of rebels’. ‘Heresy formed the first against the true religion; ambition disguised as zeal gave birth to the second’. Mercifully, divine providence subsequently granted the house of Bourbon the glory of triumphing over both of these leagues. First Henry the Great defeated the ‘League of False Zealots (Ligue des Faux-Zelez)’ with his valour and his clemency. Then Louis the Just disarmed the Calvinists by capturing the strongholds in which they had established a form of rule contrary to monarchical sovereignty. Finally Louis the Great, through his combina- tion of charity, zeal for the conversion of the heretics, and concern for the just application of the law, reduced the Protestant party to so weak a condition that its end seemed nigh. Maimbourg’s depiction of the later sixteenth century as a time of two baneful leagues reminds us that the history of how later generations recalled and passed along the story of the French Wars of Religion is a particularly complex one not merely because so many specific episodes of trauma, from local ambushes to larger massacres to political assassina- tions shook families, localities and the kingdom over nearly forty years of conflict, but also because the conflicts involved two different insurgent parties in two different phases with two different outcomes.