Shaping the Memory of the French Wars of Religion. the First Centuries Philip Benedict in 1683, the Historian Louis Maimbourg D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Vie De Cour Au Château De Versailles Avant La Révolution Française (1789)

La vie de cour au château de Versailles avant la Révolution Française (1789) Avant la Révolution*, la France est une monarchie avec à sa tête un monarque, le Roi de France. Lorsque Louis XIII décède en 1643, le futur Louis XIV, alors âgé de cinq ans, est trop jeune pour régner. C’est sa mère, Anne d’Autriche, qui est désignée régente* jusqu' à ce que son fils ait 13 ans. Les périodes de régence sont souvent des moments difficiles pour la royauté car le pouvoir est exercé par un représentant du futur roi (un membre de la famille royale, homme ou femme) ayant moins de légitimité. Durant la jeunesse de Louis XIV, la Fronde (1648-1653) déstabilise la monarchie : les parlementaires et nobles du royaume se révoltent contre le pouvoir royal. Le gouvernement est en situation délicate, même si la révolte n’aboutit pas. Le roi Louis XIV reste très marqué par cette période. Ne voulant pas que cette situation se reproduise, il rassemble la Cour autour de lui, sous son autorité . Versailles devient le siège du pouvoir de 1682 jusqu’à la Révolution Française en 1789 , sauf durant de courtes périodes où il revient à Paris. Le château de Versailles est une résidence royale, habitée par le Roi et son entourage. Ce domaine est le centre symbolique du royaume . Avant 1789, la société est divisée en 3 « ordres » (catégories) : le clergé, la noblesse et le tiers-état, c’est-à-dire le peuple. Chaque « sujet*» de France a en théorie le droit de venir présenter un problème ou une demande directement au Roi, sous condition de porter un chapeau et une épée, qui peuvent être loués à l’entrée du château. -

Mathieu De Morgues and Michel De Marillac: the Dévots and Absolutism

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 32 Issue 1 Article 2 Spring 3-6-2014 Mathieu de Morgues and Michel de Marillac: The Dévots and Absolutism Caroline Maillet-Rao Ph.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation Maillet-Rao, Caroline Ph.D. (2014) "Mathieu de Morgues and Michel de Marillac: The Dévots and Absolutism," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 32 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol32/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Mathieu de Morgues and Michel de Marillac: The Dévots and Absolutism CAROLINE MAILLET-RAO, PH.D. Translated by Gerard Cavanagh. Originally published in French History 25:3 (2011), 279-297, by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for the Study of French History. Reprinted by permission of the author and Oxford University Press, per License Agreement dated 11 July 2013. Editor’s note: following the conditions set forth by Oxford University Press this article is republished as it appeared in French History, with no alterations. As such, the editorial style differs slightly from the method typically utilized in Vincentian Heritage. Q Q Q Q QQ Q QQ QQ Q QQ QQ Q QQ Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q previous Q next Q Q BACK TO CONTENTS Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q article article Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q he dévots, the Queen Mother Marie de Médicis’ party represented by Mathieu de Morgues (1582-1670) and Michel de Marillac (1560-1632), are known as the most T ferocious adversaries of Louis XIII’s principal minister, Cardinal Richelieu. -

Zones Construites, Zones Désertes Sur Le Littoral Atlantique. Les Leçons Du Passé Built Zones, Desert Zones on the Atlantic Littoral

Norois Environnement, aménagement, société 222 | 2012 Xynthia Zones construites, zones désertes sur le littoral atlantique. Les leçons du passé Built zones, desert zones on the Atlantic littoral. Lessons of the past Martine Acerra et Thierry Sauzeau Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/norois/4048 DOI : 10.4000/norois.4048 ISBN : 978-2-7535-1843-8 ISSN : 1760-8546 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Rennes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 28 février 2012 ISBN : 978-2-7535-1815-5 ISSN : 0029-182X Référence électronique Martine Acerra et Thierry Sauzeau, « Zones construites, zones désertes sur le littoral atlantique. Les leçons du passé », Norois [En ligne], 222 | 2012, mis en ligne le 30 mars 2014, consulté le 31 mars 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/norois/4048 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/norois.4048 © Tous droits réservés NOROIS n° 222, 2012/1, p. 103-114 www.pur-editions.fr Revue en ligne : http://norois.revues.org Zones construites, zones désertes sur le littoral atlantique Les leçons du passé Built zones, desert zones on the Atlantic littoral Lessons of the past Martine Acerraa*, Thierry Sauzeaub * auteur correspondant : tel : 33 (0)2 40 14 11 05. fax : 33 (0)2 40 14 14 23 a CRHIA – EA 1163, Centre de Recherches en Histoire International et Atlantique, Université de Nantes, Chemin de la Censive-du-Tertre, BP 81227, 44 312 Nantes Cedex 3, France ([email protected]) b CRIHAM – EA 4270, Centre de Recherches Interdisciplinaires Histoire, Histoire de l’Art et Musicologie, Université de Poitiers, 36 rue de La Chaine, 86 022 Poitiers Cedex, France ([email protected]) Résumé : Cet article explore la question des relations entre les installations en zone littorale, la mémoire locale et les connaissances offi cielles sur l’environnement littoral. -

2012 Calvin Bibliography

2012 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul W. Fields and Andrew M. McGinnis (Research Assistant) I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural Context—Intellectual History C. Cultural Context—Social History D. Friends E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin’s Works A. Works and Selections B. Criticism and Interpretation III. Calvin’s Theology A. Overview B. Revelation 1. Scripture 2. Exegesis and Hermeneutics C. Doctrine of God 1. Overview 2. Creation 3. Knowledge of God 4. Providence 5. Trinity D. Doctrine of Christ E. Doctrine of the Holy Spirit F. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Overview 2. Covenant 3. Ethics 4. Free Will 5. Grace 6. Image of God 7. Natural Law 8. Sin G. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Assurance 2. Atonement 1 3. Faith 4. Justification 5. Predestination 6. Sanctification 7. Union with Christ H. Doctrine of the Christian Life 1. Overview 2. Piety 3. Prayer I. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline 3. Instruction 4. Judaism 5. Missions 6. Polity J. Worship 1. Overview 2. Images 3. Liturgy 4. Music 5. Preaching 6. Sacraments IV. Calvin and Social-Ethical Issues V. Calvin and Economic and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Overview 2. Christian Life 3. Church Discipline 4. Ecclesiology 5. Holy Spirit 6. Predestination 7. Salvation 8. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Arts 2. Cultural Context—Intellectual History 2 3. Cultural Context—Social History 4. Education 5. Literature C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. Australia 2. Eastern Europe 3. England 4. Europe 5. France 6. Geneva 7. Germany 8. Hungary 9. India 10. -

SBCO-Bull21-P245-311

Date de publication: 15-12-1990 lSSN : 0154 9898 BUUETIN DE LA SOCIÉTÉ BaTANIQUE DU CENTRE-OUEST. NOUVEUE SÉRIE. TOME 21 - 1990 245 Les paysages littoraux de la Charente-Maritime continentale entre la Seudre et la Gironde (3< partie) par Guy ESTÈVE (*) (*) G. E. Le Chêne Vert, Le Billeau, 17920 BREUILLET. 246 G. ESTÈVE Avant-propos Cette publication est le troisième et dernier volet de l'étude consacrée aux paysages littoraux de la presqu'île d'Arvert. Elle concerne les marais en rive gauche de la Seudre dont les paysages sont fortement marqués par l'interven tion de l'homme. La géologie étant relativement simple notre recherche a été autant celle de l'historien et du géographe que celle du naturaliste. Pour cela il nous a fallu consulter de très nombreux documents écrits ou cartographiques aux Archives Départementales de la Charente-Maritime, aux Archives Historiques de la Marine et dans plusieurs bibliothèques municipales (La Rochelle, Saintes, Royan) ainsi qu'au service du cadastre des différentes communes riveraines qui conservent les plans levés entre 1826 et 1837. La lecture des délibérations du Conseil Général de la Charente-Inférieure puis de la Charente-Maritime nous a permis, depuis un siècle et demi, de suivre l'évolution des problèmes posés aux sauniers et aux ostréiculteurs. Nous n'avons pas cité toutes les rèférences de ces documents, le lecteur nous fera confiance. En les reproduisant nous les avons, pour la plupart, transcrits en un français plus accessible au lecteurcontemporain, conscient d'y perdre en saveur et en pittoresque mais soucieux d'y gagner en clarté. -

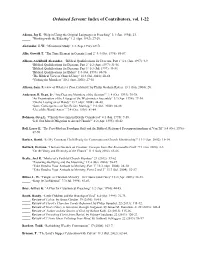

Ordained Servant: Index of Contributors, Vol. 1-22

Ordained Servant: Index of Contributors, vol. 1-22 Adams, Jay E. “Help in Using the Original Languages in Preaching” 3:1 (Jan. 1994): 23. _____. “Working with the Eldership” 1:2 (Apr. 1992): 27-29. Alexander, J. W. “Ministerial Study” 1:3 (Sep. 1992): 69-71. Allis, Oswald T. “The Time Element in Genesis 1 and 2” 4:4 (Oct. 1995): 85-87. Allison, Archibald Alexander. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 1” 6:1 (Jan. 1997): 4-9. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 2” 6:2 (Apr. 1997): 31-36. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 3” 6:3 (Jul. 1997): 49-54. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Elders” 3:4 (Oct. 1994): 80-96. _____. “The Biblical View of Church Unity” 10:3 (Jul. 2001): 60-64. _____. “Visiting the Members” 10:2 (Apr. 2001): 27-30. Allison, Sam. Review of What is a True Calvinist? by Philip Graham Ryken. 13:1 (Jan. 2004): 20. Anderson, R. Dean, Jr. “Are Deacons Members of the Session?” 2: 4 (Oct. 1993): 75-78. _____. “An Examination of the Liturgy of the Westminster Assembly” 3:2 (Apr. 1994): 27-34. _____. “On the Laying on of Hands” 13:2 (Apr. 2004): 44-48. _____. “Some Consequences of Sex Before Marriage” 9:4 (Oct. 2000): 86-88. _____. “Use of the Word ‘Amen’” 7:4 (Oct. 1998): 81-84. Bahnsen, Greg L. “Church Government Briefly Considered” 4:1 (Jan. 1995): 9-10. _____. “Is It Our Moral Obligation to Attend Church?” 4:2 (Apr. 1995): 40-42. Ball, Larry E. “The Post-Modern Paradigm Shift and the Biblical, Reformed Presuppositionalism of Van Til” 5:4 (Oct. -

The Rites of Violence: Religious Riot in Sixteenth-Century France Author(S): Natalie Zemon Davis Source: Past & Present, No

The Past and Present Society The Rites of Violence: Religious Riot in Sixteenth-Century France Author(s): Natalie Zemon Davis Source: Past & Present, No. 59 (May, 1973), pp. 51-91 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/650379 . Accessed: 29/10/2013 12:12 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Past &Present. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.205.218.77 on Tue, 29 Oct 2013 12:12:25 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE RITES OF VIOLENCE: RELIGIOUS RIOT IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE * These are the statutesand judgments,which ye shall observe to do in the land, which the Lord God of thy fathersgiveth thee... Ye shall utterly destroyall the places whereinthe nations which he shall possess served their gods, upon the high mountains, and upon the hills, and under every green tree: And ye shall overthrowtheir altars, and break theirpillars and burn their groves with fire; and ye shall hew down the gravenimages of theirgods, and the names of them out of that xii. -

Conseillers Du Roi : Une Critique Révélatrice Des Crispations Politiques Après La Saint-Barthélemy (Années 1570)

Les « meschans » conseillers du roi : une critique révélatrice des crispations politiques après la Saint-Barthélemy (années 1570) Lucas Lehéricy Sorbonne Université – Centre Roland Mousnier (UMR 8596) Après le massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy (24 août 1572), la littérature polémique, principalement protestante, se lance dans une vaste entreprise de dénonciation des méchants conseillers du roi qui, « abusans du sacré nom du Roy, de Pieté et de justice », ruinent la France à leur profit. Exploitant à satiété la caricature et n’hésitant pas à recourir aux invectives et aux mensonges les plus orduriers, ces œuvres sont particulièrement intéressantes, car, derrière l’outrance du propos, elles semblent exprimer les résistances de la société française face à la déliquescence supposée de la monarchie des Valois et le rejet de cette caste de « Méchants » qui aurait remplacé les conseillers naturels du souverain. En outre, elles proposent souvent une refonte du politique originale qui irait à rebours des évolutions proposées par les tenants de l’absolutisme royal à la même époque. After St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre (24 August 1572), controversial literature, mostly protestant, begins to denounce the mean King’s councillors who destroy France, « abusing of the holy name of King, Piety and Justice ». Using caricature, invective and even filthy lies, these books are very interesting because, despite their excessiveness, they seem to express the society’s resistance against the supposed decay of French monarchy and the reject of this group of « villains » who had replaced the true councillors of the kingdom. Moreover, they propose a political reform very different of the one offered by theoreticians of absolutism at the same period. -

Theology of the Westminster Confession, the Larger Catechism, and The

or centuries, countless Christians have turned to the Westminster Standards for insights into the Christian faith. These renowned documents—first published in the middle of the 17th century—are widely regarded as some of the most beautifully written summaries of the F STANDARDS WESTMINSTER Bible’s teaching ever produced. Church historian John Fesko walks readers through the background and T he theology of the Westminster Confession, the Larger Catechism, and the THEOLOGY The Shorter Catechism, helpfully situating them within their original context. HISTORICAL Organized according to the major categories of systematic theology, this book utilizes quotations from other key works from the same time period CONTEXT to shed light on the history and significance of these influential documents. THEOLOGY & THEOLOGICAL of the INSIGHTS “I picked up this book expecting to find a resource to be consulted, but of the found myself reading the whole work through with rapt attention. There is gold in these hills!” MICHAEL HORTON, J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary California; author, Calvin on the Christian Life WESTMINSTER “This book is a sourcebook par excellence. Fesko helps us understand the Westminster Confession and catechisms not only in their theological context, but also in their relevance for today.” HERMAN SELDERHUIS, Professor of Church History, Theological University of Apeldoorn; FESKO STANDARDS Director, Refo500, The Netherlands “This is an essential volume. It will be a standard work for decades to come.” JAMES M. RENIHAN, Dean and Professor of Historical Theology, Institute of Reformed Baptist Studies J. V. FESKO (PhD, University of Aberdeen) is academic dean and professor of systematic and historical theology at Westminster Seminary California. -

Netherlandish Culture of the Sixteenth Century SEUH 41 Studies in European Urban History (1100–1800)

Netherlandish Culture of the Sixteenth Century SEUH 41 Studies in European Urban History (1100–1800) Series Editors Marc Boone Anne-Laure Van Bruaene Ghent University © BREPOLS PUBLISHERS THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE PRINTED FOR PRIVATE USE ONLY. IT MAY NOT BE DISTRIBUTED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. Netherlandish Culture of the Sixteenth Century Urban Perspectives Edited by Ethan Matt Kavaler Anne-Laure Van Bruaene FH Cover illustration: Pieter Bruegel the Elder - Three soldiers (1568), Oil on oak panel, purchased by The Frick Collection, 1965. Wikimedia Commons. © 2017, Brepols Publishers n.v., Turnhout, Belgium. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. D/2017/0095/187 ISBN 978-2-503-57582-7 DOI 10.1484/M.SEUH-EB.5.113997 e-ISBN 978-2-503-57741-8 Printed on acid-free paper. © BREPOLS PUBLISHERS THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE PRINTED FOR PRIVATE USE ONLY. IT MAY NOT BE DISTRIBUTED WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. Table of Contents Ethan Matt Kavaler and Anne-Laure Van Bruaene Introduction ix Space & Time Jelle De Rock From Generic Image to Individualized Portrait. The Pictorial City View in the Sixteenth-Century Low Countries 3 Ethan Matt Kavaler Mapping Time. The Netherlandish Carved Altarpiece in the Early Sixteenth Century 31 Samuel Mareel Making a Room of One’s Own. Place, Space, and Literary Performance in Sixteenth-Century Bruges 65 Guilds & Artistic Identities Renaud Adam Living and Printing in Antwerp in the Late Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Centuries. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

Calvinism and Religious Toleration in France and The

CALVINISM AND RELIGIOUS TOLERATION IN FRANCE AND THE NETHERLANDS, 1555-1609 by David L. Robinson Bachelor of Arts, Memorial University of Newfoundland (Sir Wilfred Grenfell College), 2011 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Examining Board: Cheryl Fury, PhD, History, UNBSJ Sean Kennedy, PhD, Chair, History Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Joanne Wright, PhD, Political Science This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK May, 2011 ©David L. Robinson, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91828-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91828-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these.