Of Religion Really Wars of Religion?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Calvin Bibliography

2012 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul W. Fields and Andrew M. McGinnis (Research Assistant) I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural Context—Intellectual History C. Cultural Context—Social History D. Friends E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin’s Works A. Works and Selections B. Criticism and Interpretation III. Calvin’s Theology A. Overview B. Revelation 1. Scripture 2. Exegesis and Hermeneutics C. Doctrine of God 1. Overview 2. Creation 3. Knowledge of God 4. Providence 5. Trinity D. Doctrine of Christ E. Doctrine of the Holy Spirit F. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Overview 2. Covenant 3. Ethics 4. Free Will 5. Grace 6. Image of God 7. Natural Law 8. Sin G. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Assurance 2. Atonement 1 3. Faith 4. Justification 5. Predestination 6. Sanctification 7. Union with Christ H. Doctrine of the Christian Life 1. Overview 2. Piety 3. Prayer I. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline 3. Instruction 4. Judaism 5. Missions 6. Polity J. Worship 1. Overview 2. Images 3. Liturgy 4. Music 5. Preaching 6. Sacraments IV. Calvin and Social-Ethical Issues V. Calvin and Economic and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Overview 2. Christian Life 3. Church Discipline 4. Ecclesiology 5. Holy Spirit 6. Predestination 7. Salvation 8. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Arts 2. Cultural Context—Intellectual History 2 3. Cultural Context—Social History 4. Education 5. Literature C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. Australia 2. Eastern Europe 3. England 4. Europe 5. France 6. Geneva 7. Germany 8. Hungary 9. India 10. -

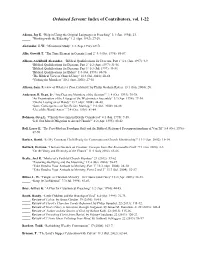

Ordained Servant: Index of Contributors, Vol. 1-22

Ordained Servant: Index of Contributors, vol. 1-22 Adams, Jay E. “Help in Using the Original Languages in Preaching” 3:1 (Jan. 1994): 23. _____. “Working with the Eldership” 1:2 (Apr. 1992): 27-29. Alexander, J. W. “Ministerial Study” 1:3 (Sep. 1992): 69-71. Allis, Oswald T. “The Time Element in Genesis 1 and 2” 4:4 (Oct. 1995): 85-87. Allison, Archibald Alexander. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 1” 6:1 (Jan. 1997): 4-9. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 2” 6:2 (Apr. 1997): 31-36. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Deacons, Part 3” 6:3 (Jul. 1997): 49-54. _____. “Biblical Qualifications for Elders” 3:4 (Oct. 1994): 80-96. _____. “The Biblical View of Church Unity” 10:3 (Jul. 2001): 60-64. _____. “Visiting the Members” 10:2 (Apr. 2001): 27-30. Allison, Sam. Review of What is a True Calvinist? by Philip Graham Ryken. 13:1 (Jan. 2004): 20. Anderson, R. Dean, Jr. “Are Deacons Members of the Session?” 2: 4 (Oct. 1993): 75-78. _____. “An Examination of the Liturgy of the Westminster Assembly” 3:2 (Apr. 1994): 27-34. _____. “On the Laying on of Hands” 13:2 (Apr. 2004): 44-48. _____. “Some Consequences of Sex Before Marriage” 9:4 (Oct. 2000): 86-88. _____. “Use of the Word ‘Amen’” 7:4 (Oct. 1998): 81-84. Bahnsen, Greg L. “Church Government Briefly Considered” 4:1 (Jan. 1995): 9-10. _____. “Is It Our Moral Obligation to Attend Church?” 4:2 (Apr. 1995): 40-42. Ball, Larry E. “The Post-Modern Paradigm Shift and the Biblical, Reformed Presuppositionalism of Van Til” 5:4 (Oct. -

The Rites of Violence: Religious Riot in Sixteenth-Century France Author(S): Natalie Zemon Davis Source: Past & Present, No

The Past and Present Society The Rites of Violence: Religious Riot in Sixteenth-Century France Author(s): Natalie Zemon Davis Source: Past & Present, No. 59 (May, 1973), pp. 51-91 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/650379 . Accessed: 29/10/2013 12:12 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Past &Present. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.205.218.77 on Tue, 29 Oct 2013 12:12:25 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE RITES OF VIOLENCE: RELIGIOUS RIOT IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE * These are the statutesand judgments,which ye shall observe to do in the land, which the Lord God of thy fathersgiveth thee... Ye shall utterly destroyall the places whereinthe nations which he shall possess served their gods, upon the high mountains, and upon the hills, and under every green tree: And ye shall overthrowtheir altars, and break theirpillars and burn their groves with fire; and ye shall hew down the gravenimages of theirgods, and the names of them out of that xii. -

Theology of the Westminster Confession, the Larger Catechism, and The

or centuries, countless Christians have turned to the Westminster Standards for insights into the Christian faith. These renowned documents—first published in the middle of the 17th century—are widely regarded as some of the most beautifully written summaries of the F STANDARDS WESTMINSTER Bible’s teaching ever produced. Church historian John Fesko walks readers through the background and T he theology of the Westminster Confession, the Larger Catechism, and the THEOLOGY The Shorter Catechism, helpfully situating them within their original context. HISTORICAL Organized according to the major categories of systematic theology, this book utilizes quotations from other key works from the same time period CONTEXT to shed light on the history and significance of these influential documents. THEOLOGY & THEOLOGICAL of the INSIGHTS “I picked up this book expecting to find a resource to be consulted, but of the found myself reading the whole work through with rapt attention. There is gold in these hills!” MICHAEL HORTON, J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary California; author, Calvin on the Christian Life WESTMINSTER “This book is a sourcebook par excellence. Fesko helps us understand the Westminster Confession and catechisms not only in their theological context, but also in their relevance for today.” HERMAN SELDERHUIS, Professor of Church History, Theological University of Apeldoorn; FESKO STANDARDS Director, Refo500, The Netherlands “This is an essential volume. It will be a standard work for decades to come.” JAMES M. RENIHAN, Dean and Professor of Historical Theology, Institute of Reformed Baptist Studies J. V. FESKO (PhD, University of Aberdeen) is academic dean and professor of systematic and historical theology at Westminster Seminary California. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

Calvinism and Religious Toleration in France and The

CALVINISM AND RELIGIOUS TOLERATION IN FRANCE AND THE NETHERLANDS, 1555-1609 by David L. Robinson Bachelor of Arts, Memorial University of Newfoundland (Sir Wilfred Grenfell College), 2011 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Examining Board: Cheryl Fury, PhD, History, UNBSJ Sean Kennedy, PhD, Chair, History Gary K. Waite, PhD, History Joanne Wright, PhD, Political Science This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK May, 2011 ©David L. Robinson, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91828-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91828-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

A Revista Dos Annales E a Produção Da História Econômica E Social

HISTÓRIA DA Dossiê temático HISTORIOGRAFIA “Do ponto de vista dos nossos Annales”: a Revista dos Annales e a produção da história econômica e social (1929-1944) “From the Annales’ point of view”: the Revue des Annales and the making of social and economic history Mariana Ladeira Osés a E-mail: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0322-1226 a Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Departamento de História, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 435 Hist. Historiogr., Ouro Preto, v. 14, n. 36, p. 435-463, maio-ago. 2021 - DOI https://doi.org/10.15848/hh.v14i36.1716 HISTÓRIA DA Artigo original HISTORIOGRAFIA RESUMO Neste artigo, propõe-se investigar a inserção da revista dos Annales, em suas décadas iniciais, na área nascente da história econômica e social, sublinhando-se as especificidades da intervenção do periódico nesse domínio disciplinar em vias de consolidação. Argumenta-se que, apesar de as ideias que veiculam não serem, em 1929, inéditas, Marc Bloch e Lucien Febvre logram, nas páginas da revista, produzir um modo de enunciação distinto de sua especialidade disciplinar, que se demonstraria mais eficaz do que os projetos concorrentes propostos por nomes destacados como Henri Sée e Henri Hauser. Para isso, procede-se tanto à exposição dessas propostas concorrentes quanto à análise verticalizada dos usos feitos, na seção crítica dos Annales d’Histoire Économique et Sociale, do rótulo “histórica econômica e social”. Busca-se, assim, investigar as especificidades desses usos, articulando-as às condições objetivas de sua formulação e avaliando seus efeitos na disputa dessa especialidade por protagonismo no seio da disciplina histórica. -

Henry IV and the Towns

Henry IV and the Towns The Pursuit of Legitimacy in French Urban Society, – S. ANNETTE FINLEY-CROSWHITE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge , United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, , United Kingdom http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk West th Street, New York, –, USA http://www.cup.org Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia © S. Annette Finley-Croswhite This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Postscript Ehrhardt / pt [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Finley-Croswhite, S. Annette Henry IV and the towns: the pursuit of legitimacy in French urban society, – / S. Annette Finley-Croswhite. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in early modern history) Includes bibliographical references. (hardback) . Henry IV, King of France, –. Urban policy – France – History – th century. Monarchy — France — History – th century. Religion and politics – France – History - th century. I. Title. II. Series. ..F '.'–dc – hardback Contents List of illustrations page x List of tables xi Acknowledgements xii Introduction France in the s and s Brokering clemency in : the case of Amiens Henry IV’s ceremonial entries: the remaking of a king Henry IV -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, If unauthorzed copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. OversKze materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMl directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMT NEITHER DECADENT, NOR TRAITOROUS, NOR STUPID: THE FRENCH AIR FORCE AND AIR DOCTRINE IN THE 1930s DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anthony Christopher Cain, M.S., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. -

Closing Down Local Hospitals in Seventeenth-Century France

Closing Down LocalHospitals in Seventeenth-Century France: The Mount Carmel and St Lazare Reform Movement Daniel Hickey* By the beginning ofthe seventeenthcentury, small hospitals in France were seen by royal and city officials as inefficient, redundant and frequently duplicating services already available. In 1672, acting upon this perception, Louis XWauthorized the arder ofNotre Dame ofMount Carmel and ofSt Lazare to undertake a vast enquiry into the operation ofthese institutions, to shutdown those which were corruptorwere notfulfilling the obligations specified in their charters, and to confiscate their holdings and revenues. This article examines the results of this experiment by looking at the operation of the Mount Carmel and St Lazare "reform" and by examining the grass-roots functioning of three small hospitals in southeastern France. Au début du dix-septième siècle, les administrateurs royaux comme ceux des grandes villes de France considéraient que les petits hôpitaux des villes et des villages étaient inefficaces et dépassés etfaisaient souvent double emploi en matière de services. Pources raisons, LouisXIVa autorisé, en 1672, l'Ordre de Notre-Dame-du-Mont-Carmel et de Saint-Lazare à entreprendre une vaste enquête sur les opérations de ces établissements, à fermer ceux qui étaient corrompus ou qui ne fournissaient pas les services exigésparleurs chartes et à confzsquer leurs biens etrevenus. Cetarticle retrace le bilan de cette expérience à la lumière des résultats de la « réforme» du Mont-Carmel et de Saint-Lazare et dufonctionnement de trois petits hôpitaux du sud-est de la France. From the beginning of the seventeenth century, French monarchs increasingly questioned the usefulness of the thousands of small institutions of poor relief scattered throughout the towns and villages of the Kingdom. -

Economic and Social Conditions in France During the 18Th Century

Economic and Social Conditions in France During the Eighteenth Century Henri Sée Professor at the University of Rennes Translated by Edwin H. Zeydel Batoche Books Kitchener 2004 Originally Published 1927 Translation of La France Économique et Sociale Au XVIIIe Siècle This edition 2004 Batoche Books [email protected] Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Land Property; its Distribution. The Population of France ........................10 Chapter 2: The Peasants and Agriculture ..................................................................... 17 Chapter 3: The Clergy .................................................................................................. 38 Chapter 4: The Nobility ................................................................................................50 Chapter 5: Parliamentary Nobility and Administrative Nobility ....................................65 Chapter 6: Petty Industry. The Trades and Guilds.......................................................69 Chapter 7: Commercial Development in the Eighteenth Century ................................. 77 Chapter 8: Industrial Development in the Eighteenth Century ...................................... 86 Chapter 9: The Classes of Workmen and Merchants................................................... 95 Chapter 10: The Financiers ........................................................................................ 103 Chapter 11: High and Middle -

Peasant Revolts During the French Wars of Religion (A Socio-Economic Comparative Study)

PEASANT REVOLTS DURING THE FRENCH WARS OF RELIGION (A SOCIO-ECONOMIC COMPARATIVE STUDY) By Emad Afkham Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Laszlo Kontler Second Reader: Professor Matthias Riedl CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection I ABSTRACT The present thesis examines three waves of the peasant revolts in France, during the French Wars of Religion. The first wave of the peasant revolts happened in southwest France in Provence, Dauphiné, and Languedoc: the second wave happened in northern France in Normandy, Brittany and Burgundy and the last one happened in western France Périgord, Limousin, Saintonge, Angoumois, Poitou, Agenais, Marche and Quercy and the whole of Guyenne. The thesis argues that the main reason for happening the widespread peasant revolts during the civil wars was due to the fundamental destruction of the countryside and the devastation of the peasant economy. The destruction of the peasant economy meant the everyday life of the peasants blocked to continue. It also keeps in the background the relationship between the incomprehensive gradual changing in the world economy in the course of the sixteenth century.