Quantifying Primary Productivity from Nazi Germany to the Inte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waffenamt Codes As Many Believe

On the internet: http://claus.espeholt.dk/mediearkiv/waae.pdf - sorted by WaA – then Period http://claus.espeholt.dk/mediearkiv/waae-a.pdf - sorted by Object – then Period http://claus.espeholt.dk/mediearkiv/waae-b.pdf - sorted by Factory – then Period http://claus.espeholt.dk/mediearkiv/waae-c.pdf - sorted by Place – then Period The list does not represent an exact “science”, but is based on observations of various items of equipment. I try to use only 100 percent sure observations - but mistakes are pos- sible anyway. 2021.09.26 Das Heereswaffenamt (From various sources: Emil Leeb: Aus der Rüstung des Dritten Reiches, Handbook on Ger- man Military Forces 1945 (US War Department), Richard D. Law: Backbone of the Wehr- macht, others) Collectors and other observers of WWII German military artifacts, especially weapons, often see small die stamps on them with a stick figure representation of the German Reich eagle and a number. Commonly referred to as “Waffenamts”, they were inspection stamps which identified the item as being inspected and passed, at some stage of its manufacturing pro- cess for the German Army. Complex items such as firearms would have multiple Waffenamts on them. When the Nazis took power in 1933, Germany started a massive re- armament program. A part of this process was the Heereswaffenamt (He.Wa.A. – Army Ordnance Office) hereafter referred to as the HWA. The beginnings of the HWA were in the Waffen- und Munitionsbeschaffungsamt of the First World War but the Waffenamt was founded officially by orders dated Nov. 8., 1919 and renamed as Heereswaffenamt on May 5., 1922. -

W12041 SU Scientia Militaria 2018 N.Indd

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 46, Nr 1, 2018. doi: 10.5787/46-1-1224 SONDERKOMMANDO DORA – SPECIAL MILITARY GEOSCIENTIFIC UNIT OF THE GERMAN COUNTER-INTELLIGENCE SERVICE IN NORTH AFRICA 1942 Hermann Häusler University of Vienna, Austria Abstract The counter-intelligence service of the German Armed Forces High Command launched Operation Dora in 1941 to update terrain information of North Africa for the German warfare and to reconnoitre the frontier between Libya and Chad. This article presents Sonderkommando Dora as an example of military geoscientific reconnaissance during World War II in the North African theatre of war where the German Armed Forces needed more accurate military geographic information on the Western Desert. The scientific personnel comprised geographers, cartographers, geologists, astronomers, meteorologists and road specialists, and they prepared special maps on the environmental setting of the Libyan Sahara. As far as it is known, these special maps were never used by Axis troops (who fought in World War II against the Allies) for tactical purposes – although it cannot be ruled out that the maps provided general information on the proximity of the German Africa Corps, the Panzer Group Africa and of the Panzer Army Africa, respectively, and also of the retreating Army Group Africa. Introduction In January 1941, the counter-intelligence service of the German Armed Forces High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht [OKW]), commanded by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, launched Operation Dora to update terrain information of North Africa for the German warfare and to reconnoitre the frontier between Libya and Chad. Sonderkommando Dora was headed by an air force colonel, and had company status. -

Air and Space Power Journal, Published Quarterly, Is the Professional Flagship Publication of the United States Air Force

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen John P. Jumper Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Donald G. Cook http://www.af.mil Commander, Air University Lt Gen Donald A. Lamontagne Commander, College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education Col Bobby J. Wilkes Editor Col Anthony C. Cain http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Senior Editor Lt Col Malcolm D. Grimes Associate Editors Lt Col Michael J. Masterson Maj Donald R. Ferguson Professional Staff Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Larry Carter, Contributing Editor http://www.au.af.mil Mary J. Moore, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager Air and Space Power Chronicles Luetwinder T. Eaves, Managing Editor The Air and Space Power Journal, published quarterly, http://www.cadre.maxwell.af.mil is the professional flagship publication of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the presentation and stimulation of innova tive thinking on military doctrine, strategy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other matters of na tional defense. The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanc tion of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If they are reproduced, Visit Air and Space Power Journal on-line the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. -

The Visual Grasp of the Fragmented Landscape Plant Geographers Vs

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Visual Grasp of the Fragmented Landscape Plant Geographers vs. Plant Sociologists Kwa, C. DOI 10.1525/hsns.2018.48.2.180 Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kwa, C. (2018). The Visual Grasp of the Fragmented Landscape: Plant Geographers vs. Plant Sociologists. Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, 48(2), 180-222. https://doi.org/10.1525/hsns.2018.48.2.180 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 CHUNGLIN KWA* The Visual Grasp of the Fragmented Landscape: Plant Geographers vs. Plant Sociologists ABSTRACT Between 1925 and 1980, landscape ecology underwent important changes through the gradual imposition of the view from above, through the uses of aerial photography. -

January/June 017

2January/June 017 The majority of Limited Edition models come with a All new items featured in this catalogue are Be sure to stay up to date with all of certificate of authenticity stating the issue number. due between January and June 2017. For more the latest Corgi news including exclusive previews information on product availability of new models and behind the scenes info via our we recommend that you visit Facebook, Twitter and YouTube pages: This is a brand new casting www.corgi.co.uk The trademarks depicted herein are used facebook.com/corgidiecast by Hornby Hobbies Limited under license or This model is a new release by permission from the respective twitter.com/corgi proprietary owners. youtube.com/officialcorgi ® ® This model is in stock now Hornby , Corgi , The Aviation Archive, The Original Omnibus, Vanguards, Super Haulers and Showcase are all registered trademarks of Contact us Hornby Hobbies Limited. NEW This model has anew design If you have any questions about the Livery ranges in the catalogue, please contact our Customer Care Team who will be All models photographed herein are handmade happy to help. samples or computer generated renders produced The contact telephone numbers are specifically for the publication of this catalogue Consumer: 01843 233525 prior to production. Trade: 01843 233502 Hornby Hobbies Ltd reserves the right to alter the products at any time. Colours and contents of the products may vary from those illustrated. Design, Art Direction, Printed in the EU Photography and Production by Hornby Hobbies Ltd. CO200826 UK Head Office Hornby Hobbies Ltd 3rd Floor, The Gateway, Innovation Way, Discovery Park, Sandwich, Kent CT13 9FF UNITED KINGDOM T: +44 (0)1843 233500 E: [email protected] PRECISION DIE- CAST MODELS CONTENTS THE CORGI HERITAGE Key to feature icons MILITARY AIRCRAFT Corgi first appeared in the toy shops of Great Britain in 1956 as a new range of die- Aviation Archive 3-17 Corgi presents The Aviation Archive, a range of high quality detailed die-cast metal model aircraft. -

Curtiss P-40

Curtiss P-40 P-40 USAAF P-40K with "shark mouth" nose art. Type Fighter aircraft Manufacturer Curtiss-Wright Corporation Maiden flight 1938 Retired 1948 (USAF) Primary users U.S. Army Air Force Royal Air Force Royal Australian Air Force American Volunteer Group Many others Produced 1939-1944 Number built 13,738 Unit cost US$60,552[1] Developed from Curtiss P-36 Variants Curtiss XP-46 The Curtiss P-40 was a US single-engine, single-seat, low-wing, all-metal fighter and ground attack aircraft which first flew in 1938, and was used in great numbers in World War II. It was a direct adaptation of the existing P-36 airframe to enable mass production of frontline fighters without significant development time. When production ceased in November 1944, 13,738 P-40s had been produced; they were used by the air forces of 28 nations and remained operational throughout the war. Warhawk was the name the United States Army Air Corps adopted for all models, making it the official name in the United States for all P-40s. British Commonwealth air forces gave the name 1 Tomahawk to models equivalent to the P-40B and P-40C and the name Kittyhawk to models equivalent to the P-40D and all later variants. The P-40's lack of a two-stage supercharger made it inferior to Luftwaffe fighters in high altitude combat, and as such the P-40 was rarely used in operations in Northwest Europe. Between 1941 and 1944, however, the P-40 played a critical role with Allied air forces in five major theaters around the world: China, the Mediterranean Theater, the South East Asian Theater, the South West Pacific Area and in Eastern Europe. -

V Okls & Supplementary Claims from Lists

O.K.L. Fighter Claims Chef für Ausz. und Dizsiplin Luftwaffen-Personalamt L.P. [A] V OKLs & Supplementary Claims from Lists Luftwaffe Campaign against the British Isles Einsatz am Kanal u. über England 26. June 1940 - 21. June 1941 26. June 1940 Einsatz am Kanal u. über England: 26.06.40 N.N. I./JG 76 Blenheim £ Amsterdam 07.30 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. 4/II-75 26.06.40 Fw. Paul Pausinger: 2 2./JG 21 Blenheim £ 20 km. W. Haarlem: 2.500 m. 08.10 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. 4/II-53B 26.06.40 Ltn. Hans-Ekkehard Bob: 5 3./JG 21 Blenheim £ 60 km. W. Rotterdam: 10 m. 18.10 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. 4/II-54B 27. June 1940 Einsatz am Kanal u. über England: 27.06.40 Ltn. Hermann Striebel: 1 5./JG 51 Hurricane £ nordwestlich Etaples 12.45 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. 4/II-18B 27.06.40 Uffz. Horst Delfs: 1 5./JG 51 Hurricane £ nordwestlich Etaples 12.45 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. 4/II-19B 27.06.40 Hptm. Horst Tietzen: 3 5./JG 51 Blenheim £ südlich Dover 20.10 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. 4/II-20B 27.06.40 Hptm. Hubertus von Bonin: 3 Stab I./JG 54 Blenheim £ - 15.15 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. 4/II-23B 27.06.40 Hptm. Hubertus von Bonin: 4 Stab I./JG 54 Blenheim £ - 15.20 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. 4/II-24B 27.06.40 Gefr. Willi Knorp: 1 2./JG 54 Blenheim £ - 15.20 OKL+JFV d.Dt.Lw. -

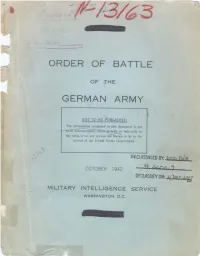

Usarmy Order of Battle GER Army Oct. 1942.Pdf

OF rTHE . , ' "... .. wti : :::. ' ;; : r ,; ,.:.. .. _ . - : , s "' ;:-:. :: :: .. , . >.. , . .,.. :K. .. ,. .. +. TABECLFCONENS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREWORD iii - vi PART A - THE GERMAN HIGH COMMAND I INTRODUCTION....................... 2 II THE DEFENSE MINISTRY.................. 3 III ARMY GHQ........ 4 IV THE WAR DEPARTMENT....... 5 PART B - THE BASIC STRUCTURE I INTRODUCTION....................... 8 II THE MILITARY DISTRICT ORGANIZATION,- 8 III WAR DEPARTMENT CONTROL ............ 9 IV CONTROL OF MANPOWER . ........ 10 V CONTROL OF TRAINING.. .. ........ 11 VI SUMMARY.............. 11 VII DRAFT OF PERSON.NEL .... ..... ......... 12 VIII REPLACEMENT TRAINING UNITS: THE ORI- GINAL ALLOTMENENT.T. ...... .. 13 SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENTS... ........ 14 THE PRESENT ALLOTMENT..... 14 REPLACEMENT TRAINING UNITS IN OCCUPIED TERRITORY ..................... 15 XII MILITARY DISTRICTS (WEHRKREISE) . 17 XIII OCCUPIED COUNTRIES ........ 28 XIV THE THEATER OF WAR ........ "... 35 PART C - ORGANIZATIONS AND COMMANDERS I INTRODUCTION. ... ."....... 38 II ARMY GROUPS....... ....... .......... ....... 38 III ARMIES........... ................. 39 IV PANZER ARMIES .... 42 V INFANTRY CORPS.... ............. 43 VI PANZER CORPS...... "" .... .. :. .. 49 VII MOUNTAIN CORPS ... 51 VIII CORPS COMMANDS ... .......... :.. '52 IX PANZER DIVISIONS .. " . " " 55 X MOTORIZED DIVISIONS .. " 63 XI LIGHT DIVISIONS .... .............. : .. 68 XII MOUNTAIN DIVISIONS. " """ ," " """ 70 XII CAVALRY DIVISIONS.. .. ... ". ..... "s " .. 72 XIV INFANTRY DIVISIONS.. 73 XV "SICHERUNGS" -

II. Tadeusz Peiper: Biographical and Intellectual Contexts 30

University of Alberta The Interrupted Narrative. Tadeusz Peiper and His Vision of Literature (1918-1939) by Piotr Grella-Mozejko © A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature Edmonton, Alberta Fall 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46324-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46324-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Member of the Food Chain?: Quantifying Primary Productivity from Nazi Germany to the International Biological Program, 1933-74 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1hz8t97m Author Lawrence, Adam Christopher Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Member of the Food Chain?: Quantifying Primary Productivity from Nazi Germany to the International Biological Program, 1933-1974 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Adam Christopher Lawrence 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Member of the Food Chain?: Quantifying Primary Productivity from Nazi Germany to the International Biological Program, 1933-1974 by Adam Christopher Lawrence Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Soraya de Chadarevian, Chair A Member of the Food Chain?: Quantifying Primary Productivity from Nazi Germany to the International Biological Program, 1929-1989, tells the story of primary productivity, one of the fundamental measurements of the ecological and earth sciences today. Primary productivity is used in biology to refer to the aggregate photosynthetic production of the plant life of a particular region. Thanks to the rule of thermodynamics, most scientists have regarded the ability of plants to produce carbohydrates using carbon dioxide, water, and solar energy as foundational to all life throughout the twentieth century. Yet the history of the theory and methods used to quantify primary productivity is more complex than the straightforward and seemingly apolitical nature of the idea might initially suggest. -

TURNIER-DATENBANK / TOURNAMENT DATABASE: 1897-1919 Last Updated: December 3Rd, 2019

TURNIER-DATENBANK / TOURNAMENT DATABASE: 1897-1919 last updated: December 3rd, 2019 GR: greco-roman Style, F/CACC: Freestyle Date City Winner 16.08.1897 Brussels / Belgium Maurice Gambier World Middleweight Championship 1898 Roubaix / France Constant le Boucher 10. (?) 1898 Paris / France Wladyslaw Pytlasinski 27.12.1898 Paris / France Paul Pons World Heavyweight Championship 1899 Savona / Italy Paul Pons 13.02.1899 Paris / France Wladyslaw Pytlasinski 16.02.1899 Bordeaux / France Paul Pons 09.03.1899 Antwerp (Antwerpen) / Belgium Constant le Boucher 13.03.1899 St. Petersburg / Russia Wladyslaw Pytlasinski 24.03.1899 Verviers / Belgium Aimable de la Calmette (Ainé) 31.03.1899 Turin / Italy Paul Pons 04.1899 Rome / Italy Paul Pons 08.04.1899 Liege / Belgium Constant le Boucher, Auguste Robinet & Pietro II 15.04.1899 Milan (Mailand) / Italy Paul Pons 24.04.1899 Brussels / Belgium Constant le Boucher & Pietro II 02.05.1899 Gent / Belgium Constant le Boucher 09.05.1899 St. Petersburg / Russia Nicolai Petroff 16.05.1899 Charleroi / Belgium Constant le Boucher 27.05.1899 Brussels / Belgium Constant le Boucher 16.07.1899 Bochum / Germany Heinrich Eberle 22.08.1899 Namur / Belgium Constant le Boucher & Ignace Nollys 09.1899 La Louviére / Belgium Constant le Boucher 11.1899 Avignon / France ? 19.11.1899 Wroclaw (Breslau) / Poland Wladyslaw Pytlasinski 15.12.1899 Toulouse / France Aimable de la Calmette (Ainé) 26.11.1899 Paris / France Maurice Gambier World Lightweight Championship 05.12.1899 Paris / France Laurent le Beaucairois World Heavyweight -

Heinz Ellenberg (1913-1997)

Tuexenia 17:5-10. Göttingen 1997. Heinz Ellenberg (1913-1997) Am 2. Mai 1997 verstarb unser ehemaliger Vorsitzender und Ehrenmitglied, Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. muh. Heinz Ellenberg im 84. Lebensjahr. Mit ihm ist einer der größten Gelehrten unseres Jahrhunderts im Bereich der Vegetationsökologie von uns gegangen. Heinz Ellenberg war eines unserer ältesten Mitglieder und schon in der „Floristisch- soziologischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft in Niedersachsen“ vor dem 2. Weltkrieg aktiv. Obwohl aufgrund vieler anderer Verpflichtungen und Interessen die Bindungen später lockerer wur den, hat er 1971 ohne Zögern den Vorsitz unserer Arbeitsgemeinschaft übernommen, als unser langjähriger Präsident Reinhold Tüxen aus Altersgründen zurücktrat. In den folgen den Jahren des Umbruchs hat er dafür gesorgt, daß unsere Arbeitsgemeinschaft sich in ab- 5 gesichertem Rahmen weiter entwickeln konnte. Auf der Jahrestagung 1977 in Neusiedl am See wurde Heinz Ellenberg zum Ehrenmitglied ernannt. Mit einer umfangreichen Fest schrift zum 70. Geburtstag (Tuexenia 3/1983) haben wir ihm unseren Dank abgestattet und sein Lebenswerk gewürdigt. Das Wirken von Heinz Ellenberg für unsere Arbeitsgemeinschaft geht aber weit über diese mehr organisatorischen Leistungen hinaus. Als begeisternder Lehrer, ideenreicher Initiator wissenschaftlicher Fragestellungen und Programme, als Verfasser grundlegender Bücher und sehr zahlreicher Publikationen, als überzeugender Diskussionsteilnehmer und nicht zuletzt als stets hilfreich-freundschaftlicher Partner hat er viele unserer Mitglieder direkt