Chapter 3 the COLONIAL COLLEGE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Benjamin Franklin Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8385/benjamin-franklin-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-28385.webp)

Benjamin Franklin Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Benjamin Franklin Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2000 Revised 2018 January Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003048 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm73021451 Prepared by Division Staff Revised and expanded by Donna Ellis Collection Summary Title: Benjamin Franklin Papers Span Dates: 1726-1907 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1770-1789) ID No.: MSS21451 Creator: Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790 Extent: 8,000 items ; 40 containers ; 12 linear feet ; 12 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Statesman, publisher, scientist, and diplomat. Correspondence, journals, records, articles, and other material relating to Franklin's life and career. Includes manuscripts (1728) of his Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion; negotiations in London (1775); letterbooks (1779-1782) of the United States legation in Paris; records (1780-1783) of the United States peace commissioners, including journals kept by Franklin and Richard Oswald; and papers (1781-1818) of Franklin's grandson, William Temple Franklin (1760-1823). Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Adams, John, 1735-1826--Correspondence. Bache, Richard, 1737-1811--Correspondence. Carmichael, William, -1795--Correspondence. Cushing, Thomas, 1725-1788--Correspondence. Dumas, Charles Guillaume Frédéric, 1721-1796--Correspondence. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Winter 2017 Antonia Pugh-Thomas

Drumming up something new WINTER 2017 ANTONIA PUGH-THOMAS Haute Couture Shrieval Outfits for Lady High Sheriffs 0207731 7582 659 Fulham Road London, SW6 5PY www.antoniapugh-thomas.co.uk Volume 36 Issue 2 Winter 2017 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL 14 20 Officers and Council November 2016 to November 2017 OFFICERS Chairman The Hon HJH Tollemache 30 38 Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary J H A Williams Esq Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory Esq DL Thorpland Hall, Fakenham Norfolk NR21 0HD Tel 01328 862392 Email [email protected] COUNCIL Col M G C Amlôt OBE DL Canon S E A Bowie DL Mrs E J Hunter D C F Jones Esq DL JAT Lee Esq OBE Mrs VA Lloyd DL Lt Col AS Tuggey CBE DL W A A Wells Esq TD (Hon Editor of The High Sheriff ) Mrs J D J Westoll MBE DL Mrs B Wilding CBE QPM DL The High Sheriff is published twice a year by Hall-McCartney Ltd for the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales Hon Editor Andrew Wells Email [email protected] ISSN 1477-8548 4 From the Editor 13 Recent Events – 20 General Election © 2017 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales From the new Chairman The City and the Law The Association is not as a body responsible for the opinions expressed 22 News – from in The High Sheriff unless it is stated Chairman’s and about members that an article or a letter officially 6 14 Recent represents the Council’s views. -

The American Revolution

The American Revolution The American Revolution Theme One: When hostilities began in 1775, the colonists were still fighting for their rights as English citizens within the empire, but in 1776 they declared their independence, based on a proclamation of universal, “self-evident” truths. Review! Long-Term Causes • French & Indian War; British replacement of Salutary Neglect with Parliamentary Sovereignty • Taxation policies (Grenville & Townshend Acts); • Conflicts (Boston Massacre & Tea Party, Intolerable Acts, Lexington & Concord) • Spark: Common Sense & Declaration of Independence Second Continental Congress (May, 1775) All 13 colonies were present -- Sought the redress of their grievances, NOT independence Philadelphia State House (Independence Hall) Most significant acts: 1. Agreed to wage war against Britain 2. Appointed George Washington as leader of the Continental Army Declaration of the Causes & Necessity of Taking up Arms, 1775 1. Drafted a 2nd set of grievances to the King & British People 2. Made measures to raise money and create an army & navy Olive Branch Petition -- Moderates in Congress, (e.g. John Dickinson) sought to prevent a full- scale war by pledging loyalty to the King but directly appealing to him to repeal the “Intolerable Acts.” Early American Victories A. Ticonderoga and Crown Point (May 1775) (Ethan Allen-Vt, Benedict Arnold-Ct B. Bunker Hill (June 1775) -- Seen as American victory; bloodiest battle of the war -- Britain abandoned Boston and focused on New York In response, King George declared the colonies in rebellion (in effect, a declaration of war) 1.18,000 Hessians were hired to support British forces in the war against the colonies. 2. Colonials were horrified Americans failed in their invasion of Canada (a successful failure-postponed British offensive) The Declaration of Independence A. -

Mary Neill Whitelaw (1840-1925) Biography

THE LIFE OF MARY NEILL WHITELAW 1840-1925 A DOCUMENTARY BIOGRAPHY WITH AN APPENDIX OF NEILL FAMILY DOCUMENTS By Susan Love Whitelaw 2004 With Grateful Acknowledgement of Contributions by: Margaret Ruth Fluharty Dot Shaw Harrison Anne Smith Kepner Bill Whitford Mary Elizabeth Williams Enerson Jean Young And Special Thanks to: Sue Cashatt, current owner of the old Whitelaw home in Kidder, MO 1 PREFACE This document is in two parts: 1. A “documentary biography” of my great grandmother, Mary Neill Whitelaw (1840- 1925), a nineteenth century Scottish immigrant who lived and raised a family in Kidder, a small town in northwest Missouri. 2. An extensive Appendix containing letters, newspaper articles, and other material relating to Mary Neill Whitelaw’s family of origin and to her origins in Scotland. The main purpose of the documentary biography is to pull together all available material on Mary Neill Whitelaw in a chronological format. I have stuck closely to the documents available and have not tried to embellish or speculate on aspects of Mary Neill Whitelaw’s life about which the written record is silent. Thus, the coverage of her life is uneven, depending as it does on the sources available. There is much more material concerning her later years (1900-1925), when her children were adults and writing letters, than about her earlier ones The material for the documentary biography comes mainly from the estate of her granddaughter, Mary Elizabeth Williams Enerson, who died in 2002, leaving a large archive of family letters and memorabilia. Much of this material she inherited from her mother, Ruth Whitelaw Williams (1872-1950), Mary Neill Whitelaw’s daughter. -

A LONG ROAD to ABOLITIONISM: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN'stransformation on SLAVERY a University Thesis Presented

A LONG ROAD TO ABOLITIONISM: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN’STRANSFORMATION ON SLAVERY ___________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of of California State University, East Bay ___________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History ___________________ By Gregory McClay September 2017 A LONG ROAD TO ABOLITIONISM: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN'S TRANSFORMATION ON SLAVERY By Gregory McClay Approved: Date: ..23 ~..(- ..2<> t""J ;.3 ~ ~11- ii Scanned by CamScanner Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………1 Existing Research………………………………………………………………….5 Chapter 1: A Man of His Time (1706-1762)…………………………………………….12 American Slavery, Unfree Labor, and Franklin’s Youth………………………...12 Franklin’s Early Writings on Slavery, 1730-1750……………………………….17 Franklin and Slavery, 1751-1762………………………………………………...23 Summary………………………………………………………………………....44 Chapter 2: Education and Natural Equality (1763-1771)………………………………..45 John Waring and the Transformation of 1763…………………………………...45 Franklin’s Ideas on Race and Slavery, 1764-1771……………………………....49 The Bray Associates and the Schools for Black Education……………………...60 The Georgia Assembly…………………………………………………………...63 Summary…………………………………………………………………………68 Chapter 3: An Abolitionist with Conflicting Priorities (1772-1786)…………………….70 The Conversion of 1772…………….……………………………………………72 Somerset v. Stewart………………………………………………………………75 Franklin’s Correspondence, 1773-1786………………………………………….79 Franklin’s Writings during the War Years, 1776-1786………………………….87 Montague and Mark -

A General History of the Burr Family, 1902

historyAoftheBurrfamily general Todd BurrCharles A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE BURR FAMILY WITH A GENEALOGICAL RECORD FROM 1193 TO 1902 BY CHARLES BURR TODD AUTHOB OF "LIFE AND LETTERS OF JOBL BARLOW," " STORY OF THB CITY OF NEW YORK," "STORY OF WASHINGTON,'' ETC. "tyc mis deserves to be remembered by posterity, vebo treasures up and preserves tbe bistort of bis ancestors."— Edmund Burkb. FOURTH EDITION PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY <f(jt Jtnuhtrboclur $«88 NEW YORK 1902 COPYRIGHT, 1878 BY CHARLES BURR TODD COPYRIGHT, 190a »Y CHARLES BURR TODD JUN 19 1941 89. / - CONTENTS Preface . ...... Preface to the Fourth Edition The Name . ...... Introduction ...... The Burres of England ..... The Author's Researches in England . PART I HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL Jehue Burr ....... Jehue Burr, Jr. ...... Major John Burr ...... Judge Peter Burr ...... Col. John Burr ...... Col. Andrew Burr ...... Rev. Aaron Burr ...... Thaddeus Burr ...... Col. Aaron Burr ...... Theodosia Burr Alston ..... PART II GENEALOGY Fairfield Branch . ..... The Gould Family ...... Hartford Branch ...... Dorchester Branch ..... New Jersey Branch ..... Appendices ....... Index ........ iii PART I. HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL PREFACE. HERE are people in our time who treat the inquiries of the genealogist with indifference, and even with contempt. His researches seem to them a waste of time and energy. Interest in ancestors, love of family and kindred, those subtle questions of race, origin, even of life itself, which they involve, are quite beyond their com prehension. They live only in the present, care nothing for the past and little for the future; for " he who cares not whence he cometh, cares not whither he goeth." When such persons are approached with questions of ancestry, they retire to their stronghold of apathy; and the querist learns, without diffi culty, that whether their ancestors were vile or illustrious, virtuous or vicious, or whether, indeed, they ever had any, is to them a matter of supreme indifference. -

Martin's Bench and Bar of Philadelphia

MARTIN'S BENCH AND BAR OF PHILADELPHIA Together with other Lists of persons appointed to Administer the Laws in the City and County of Philadelphia, and the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania BY , JOHN HILL MARTIN OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR OF C PHILADELPHIA KKKS WELSH & CO., PUBLISHERS No. 19 South Ninth Street 1883 Entered according to the Act of Congress, On the 12th day of March, in the year 1883, BY JOHN HILL MARTIN, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. W. H. PILE, PRINTER, No. 422 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Stack Annex 5 PREFACE. IT has been no part of my intention in compiling these lists entitled "The Bench and Bar of Philadelphia," to give a history of the organization of the Courts, but merely names of Judges, with dates of their commissions; Lawyers and dates of their ad- mission, and lists of other persons connected with the administra- tion of the Laws in this City and County, and in the Province and Commonwealth. Some necessary information and notes have been added to a few of the lists. And in addition it may not be out of place here to state that Courts of Justice, in what is now the Com- monwealth of Pennsylvania, were first established by the Swedes, in 1642, at New Gottenburg, nowTinicum, by Governor John Printz, who was instructed to decide all controversies according to the laws, customs and usages of Sweden. What Courts he established and what the modes of procedure therein, can only be conjectur- ed by what subsequently occurred, and by the record of Upland Court. -

By Thomas Spence Duché the Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

WILLIAM RAWLE, 1759-1836 By Thomas Spence Duché THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Artist in Exile The Story of Thomas Spence Duché HEN Thomas Spence Duché was born on September 15, 1763, it was into what seemed an assured place in Phila- Wdelphia and its society. His father, the Reverend Jacob Duché, had just been ordained into priest's orders in the Church of England and had entered upon his duties as the assistant minister of Christ Church and St. Peter's, and it was to Christ Church that the boy was taken for baptism on October 16, 17631; his mother was a Hopkinson, the daughter of Thomas Hopkinson and sister of Francis. The world of 1763 must have seemed extremely stable to most of the members of Thomas's family and their friends. The young king, George III, had been on the throne for three years, his accession having been celebrated at the College of Philadelphia in 1762 by a dialogue and ode exercise, written by Jacob Duche and Francis Hopkinson. Three years after the boy's birth, almost coincident with the repeal of the Stamp Act, two of his uncles, Hopkinson and John Morgan, in competition for a medal presented to the College of Philadelphia by John Sargent, wrote essays on "The Reciprocal Advantages Arising from a Perpetual Union between Great Britain and Her American Colonies." As a trustee, Jacob Duche was one of the judges who awarded first prize to John Morgan, though he did 1 Manuscript Collections of the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania, CII, 551. -

In the Polite Eighteenth Century, 1750–1806 A

AMERICAN SCIENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF “USEFUL KNOWLEDGE” IN THE POLITE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, 1750–1806 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Elizabeth E. Webster Christopher Hamlin, Director Graduate Program in History and Philosophy of Science Notre Dame, Indiana April 2010 © Copyright 2010 Elizabeth E. Webster AMERICAN SCIENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF “USEFUL KNOWLEDGE” IN THE POLITE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, 1750–1806 Abstract by Elizabeth E. Webster In this thesis, I will examine the promotion of science, or “useful knowledge,” in the polite eighteenth century. Historians of England and America have identified the concept of “politeness” as a key component for understanding eighteenth-century culture. At the same time, the term “useful knowledge” is also acknowledged to be a central concept for understanding the development of the early American scientific community. My dissertation looks at how these two ideas, “useful knowledge” and “polite character,” informed each other. I explore the way Americans promoted “useful knowledge” in the formative years between 1775 and 1806 by drawing on and rejecting certain aspects of the ideal of politeness. Particularly, I explore the writings of three central figures in the early years of the American Philosophical Society, David Rittenhouse, Charles Willson Peale, and Benjamin Rush, to see how they variously used the language and ideals of politeness to argue for the promotion of useful knowledge in America. Then I turn to a New Englander, Thomas Green Fessenden, who identified and caricatured a certain type of man of science and satirized the late-eighteenth-century culture of useful knowledge. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

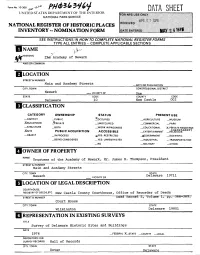

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building.