Babelsberg/Babylon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ein Deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme Und Der Deutschen Not

Jörg Hackfurth (Gießen) Ein deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme und der Deutschen Not 1. Einleitung In From Caligari to Hitler formuliert der Soziologe Siegfried Kracauer die These, daß „mittels einer Analyse der deutschen Filme tiefenpsychologi- sche Dispositionen, wie sie in Deutschland von 1918 bis 1933 herrschten, aufzudecken sind: Dispositionen, die den Lauf der Ereignisse zu jener Zeit beeinflussen und mit denen in der Zeit nach Hitler zu rechnen sein wird".1 Kracauers analytische Methode beruht auf einigen Prämissen, die hier noch einmal in ihrem originalen Wortlaut wiedergegeben werden sollen: „Die Filme einer Nation reflektieren ihre Mentalität unvermittelter als an- dere künstlerische Medien, und das aus zwei Gründen: Erstens sind Filme niemals das Produkt eines Individuums. [...] Da jeder Filmproduktionsstab eine Mischung heterogener Interessen und Neigungen verkörpert, tendiert die Teamarbeit auf diesem Gebiet dazu, willkürliche Handhabung des Filmmaterials auszuschließen und individuelle Eigenheiten zugunsten jener zu unterdrücken, die vielen Leuten gemeinsam sind. Zweitens richten sich Filme an die anonyme Menge und sprechen sie an. Von populären Filmen [...] ist daher anzunehmen, daß sie herrschende Massenbedürfnisse befrie- digen“2 Daraus resultiert ein Mechanismus, der sowohl in Hollywood als auch in Deutschland Geltung hat: „Hollywood kann es sich nicht leisten, Sponta- neität auf Seiten des Publikums zu ignorieren. Allgemeine Unzufriedenheit zeigt sich in rückläufigen Kasseneinnahmen, und die Filmindustrie, für die Profitinteresse eine Existenzfrage ist, muß sich so weit wie möglich den Veränderungen des geistigen Klimas anpassen".3 Ferner gilt: „Was die Filme reflektieren, sind weniger explizite Überzeu- gungen als psychologische Dispositionen – jene Tiefenschichten der Kol- lektivmentalität, die sich mehr oder weniger unterhalb der Bewußtseins- dimension erstrecken. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

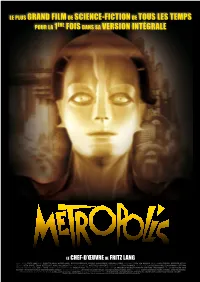

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Renan De Andrade Varolli

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS RENAN DE ANDRADE VAROLLI O MODERNO NA ILUMINAÇÃO ELÉTRICA EM BERLIM NOS ANOS 1920 SÃO PAULO 2017 RENAN DE ANDRADE VAROLLI O MODERNO NA ILUMINAÇÃO ELÉTRICA EM BERLIM NOS ANOS 1920 Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em História da Arte Universidade Federal de São Paulo Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Arte Linha de Pesquisa: Arte: Circulações e Transferências Orientação: Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten SÃO PAULO 2017 Varolli, Renan de Andrade. O moderno na iluminação elétrica em Berlim nos anos 1920 / Renan de Andrade Varolli. São Paulo, 2017. 129 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em História da Arte) – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Programa de Pós- Graduação em História da Arte, 2017. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten. 1. Teoria da Arte. 2. História da Arte. 3. Teoria da Arquitetura. I. Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten. II. O moderno na iluminação elétrica em Berlim nos anos 1920. RENAN DE ANDRADE VAROLLI O MODERNO NA ILUMINAÇÃO ELÉTRICA EM BERLIM NOS ANOS 1920 Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em História da Arte Universidade Federal de São Paulo Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Arte Linha de Pesquisa: Arte: Circulações e Transferências Orientação: Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten Aprovação: ____/____/________ Prof. Dr. Jens Michael Baumgarten Universidade Federal de São Paulo Prof. Dr. Luiz César Marques Filho Universidade Estadual de Campinas Profa. Dra. Yanet Aguilera Viruéz Franklin de Matos Universidade Federal de São Paulo AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço às seguintes pessoas, que tornaram possível a realização deste trabalho: Aline, Ana Carolina, minha prima, Ana Paula, Bi, Carla, Daniel, Diana, Fá, Fê, Gabi, Gabriel, Giovanna, Jair, meu pai, Jane, minha tia e madrinha, Prof. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

Verfasser Der Bände I Bis X

schwarz gelb cyan magenta TypoScript GmbH Fr 29.09.2017 12:33:27 z:/jehle/inmedialo/hbGrund/hgr S.1027 Verfasser der Bände I bis X Dr. h.c. Giorgos Arestis, University of Central Lancashire, Zypern, Richter am EuGH a.D. Professor Dr. Dres. h.c. Rainer Arnold, Universität Regensburg Professor Dr. Jean-Fran¸cois Aubert, Universität Neuenburg (Neuchˆatel) Professor Dr. Suren Avakian, Lomonossov-Universität Moskau Professor Dr. Peter Axer, Universität Heidelberg Professor Dr. Peter Badura, Universität München Dr. Snjeˇzana Bagi´c, Vizepräsidentin des Verfassungsgerichtshofs, Zagreb Professor Dr. Dr. h.c. mult. Bogusław Banaszak, Universität Zielona Gora ´ Professor Dr. Hartmut Bauer, Universität Potsdam Professor Dr. Gerhard Baumgartner, Universität Klagenfurt Professor Dr. Florian Becker, Universität Kiel Professor Dr. Wilfried Berg, Universität Bayreuth Professor Dr. Dr. h.c. Rudolf Bernhardt, Universität Heidelberg Professor Dr. Herbert Bethge, Universität Passau Professor Dr. Giovanni Biaggini,UniversitätZürich Siniˇsa Bjekovi´c, M.A., Bürgerbeauftragter, Universität Podgorica Professor Dr. Hermann-Josef Blanke, Universität Erfurt Professor Dr. Armin von Bogdandy, Max-Planck-Institut Heidelberg Professor Dr. Michael Brenner, Universität Jena Professor Dr. Jürgen Bröhmer, University of New England (Australien) Professor Dr. Alexander Bröstl, Paneuropäische Hochschule Bratislava Professor Dr. Dr. h.c. Georg Brunner †, Universität zu Köln Professor Dr. Brun-Otto Bryde, Universität Gießen Professor Dr. Martin Burgi, Universität München Professor Dr. Christian Calliess, Freie Universität Berlin Professor Dr. Dr. h.c. Axel Freiherr von Campenhausen, Universität Göttingen Professor Dr. Claus Dieter Classen, Universität Greifswald Professor Dr. Christian von Coelln, Universität zu Köln Professor Dr. Thomas von Danwitz, Richter am EuGH, Luxemburg Professor Dr. Hans-Georg Dederer, Universität Passau Professor Dr. -

Film Posters Das Höchste Gesetz Der Natur

Filmplakate Film Posters Das höchste Gesetz der Natur Die Überlieferung zu diesem Film ist recht What we know about this film is quite sparse. dünn. Weder Regisseur noch Mitwirkende sind Neither the director nor the cast are known, bekannt, auch die nationale Produktion bzw. and even the national production and its year das Entstehungsjahr bleiben unklar. Überlie- of origin remain uncertain. What is known is fert ist jedoch ein durch die Berliner Polizei that the Berlin police issued a ban on screen- erteiltes Verbot der Aufführung vor Kindern. ings for children. In 1916 the Lichtbild-Bühne, Die „Lichtbild-Bühne“ beschreibt den Film 1916 no. f20, described the film as a dramatic Wild als dramatisches Wildwestschauspiel in drei West spectacle in three acts “that even a well- Akten, „an dem auch der wohlgesittete Euro- mannered European will enjoy.” päer sein Gefallen findet“. The only colored photograph included here, Das einzig kolorierte und damit augenfälligste and therefore the most conspicuous, shows a Foto des Plakats zeigt ein betendes Kind mit praying child with properly folded hands and artig gefalteten Händen und empor gerichteten eyes cast upwards. The woman next to the Augen. Die Frau daneben scheint jemand an- child seems to have someone else in view. The deren im Blick zu haben. Die um den Textblock smaller photos grouped around the text block gruppierten kleineren Fotos führen uns durch lead us through the plot of the film. It is the die Handlung des Films. story of two lovers whose paths have parted. Es ist die Geschichte zweier Liebender, deren A jovial third party appears, but is spurned. -

Hitler's Third Reich

#61 The Legs of Iron – Hitler’s Third Reich Key Understanding: The Third Reich. Hitler’s Third Reich, or Third Empire, was based on the concept of a Christian Millennium, with the First Reich, or First Empire, considered to be the Holy Roman Empire of 800-1806. Das Dritte Reich. We are addressing this somewhat prematurely, but it adds to our millennial conversation. The descriptive phrase “Third Reich” was first coined in a 1923 book (left) Das Dritte Reich (“The Third Reich”) published by German Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. In German history, two periods were distinguished: (1) The Holy Roman Empire of 800-1806. This was the First Reich. (2) The German Empire of 1871-1918. This was the Second Reich. The Third Reich. The Second Reich would soon be followed by a Third Reich, Hitler’s Germany. In a speech on November 27, 1937, Hitler commented on his plans to have major parts of Berlin torn down and rebuilt. His words included, “ . to build a millennial city adequate to a thousand year old people with a thousand year old and cultural past, for its never-ending glorious future.” He was referring back to the Holy Roman Empire. Adolf Hitler Instead of lasting 1000 years, Hitler’s Third Reich lasted but “a short space” of 12 years. We use that phrase for a reason, of course. We will come back to Hitler’s Germany, and exactly where it is in prophecy (besides it being an attempted counterfeit of Rev. 20:1-4), but we need to move on. Revelation 20:1-4 (KJV) And I saw an angel come down from heaven, having the key of the bottomless pit and a great chain in his hand.