Domestic Violence Act of 2010? ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Esdo Profile 2021

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE 2021 Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) 1. BACKGROUND Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

Esdo Profile

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) 1. Background Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

Bangladesh Rice Journal Bangladesh Rice Journal

ISSN 1025-7330 BANGLADESH RICE JOURNAL BANGLADESH RICE JOURNAL BANGLADESH RICE JOURNAL VOL. 21 NO. 2 (SPECIAL ISSUE) DECEMBER 2017 The Bangladesh Rice Journal is published in June and December by the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI). The journal is a peer reviewed one based on original Theme : Cropping Patterns of Bangladesh research related to rice science. The manuscript should be less than eight printed journal pages or about 12 type written pages. An article submitted to the Bangladesh Rice Journal must not have been published in or accepted for publication by any other journal. DECEMBER 2017 ISSUE) NO. 2 (SPECIAL VOL. 21 Changes of address should be informed immediately. Claims for copies, which failed to reach the paid subscribers must be informed to the Chief Editor within three months of the publication date. Authors will be asked to modify the manuscripts according to the comments of the reviewers and send back two corrected copies and the original copy together to the Chief Editor within the specified time, failing of which the paper may not be printed in the current issue of the journal. BRJ: Publication no.: 263; 2000 copies BANGLADESH RICE RESEARCH INSTITUTE Published by the Director General, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, Gazipur 1701, Bangladesh GAZIPUR 1701, BANGLADESH Printed by Swasti Printers, 25/1, Nilkhet, Babupura, Dhaka 1205 ISSN 1025-7330 BANGLADESH RICE JOURNAL VOL. 21 NO. 2 (SPECIAL ISSUE) DECEMBER 2017 Editorial Board Chief Editor Dr Md Shahjahan Kabir Executive Editors Dr Md Ansar Ali Dr Tamal Lata Aditya Associate Editors Dr Krishna Pada Halder Dr Md Abdul Latif Dr Abhijit Shaha Dr Munnujan Khanam Dr AKM Saiful Islam M A Kashem PREFACE Bangladesh Rice Journal acts as an official focal point for the delivery of scientific findings related to rice research. -

Bounced Back List.Xlsx

SL Cycle Name Beneficiary Name Bank Name Branch Name Upazila District Division Reason for Bounce Back 1 Jan/21-Jan/21 REHENA BEGUM SONALI BANK LTD. NA Bagerhat Sadar Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 23-FEB-21-R03-No Account/Unable to Locate Account 2 Jan/21-Jan/21 ABDUR RAHAMAN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number SHEIKH 3 Jan/21-Jan/21 KAZI MOKTADIR HOSEN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 4 Jan/21-Jan/21 BADSHA MIA SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 5 Jan/21-Jan/21 MADHAB CHANDRA SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number SINGHA 6 Jan/21-Jan/21 ABDUL ALI UKIL SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 7 Jan/21-Jan/21 MRIDULA BISWAS SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 8 Jan/21-Jan/21 MD NASU SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 9 Jan/21-Jan/21 OZIHA PARVIN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 10 Jan/21-Jan/21 KAZI MOHASHIN SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 11 Jan/21-Jan/21 FAHAM UDDIN SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. NA Chitalmari Upazila Bagerhat Khulna 16-FEB-21-R04-Invalid Account Number 12 Jan/21-Jan/21 JAFAR SHEIKH SONALI BANK LTD. -

Impacts of Northwest Fisheries Extension Project (NFEP) on Pond Fish Farming in Improving Livelihood Approach

J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 8(2): 305–311, 2010 ISSN 1810-3030 Impacts of Northwest Fisheries Extension Project (NFEP) on pond fish farming in improving livelihood approach M. R. Islam1 and M. R. Haque2 1Department of Fisheries Biology and Genetics, 2Department of Fisheries Management, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh Abstract Investigation was carried out from June to August 2009. A total of 40 fish farmers were selected from northwest two upazila namely Debigonj (n=20) and Boda (n=20) where both men and women were targeted. Focus group discussion (FGD) and cross-check interview were conducted to get an overview on carp farming. From 1991-1995, 1996-2000 and after 2000; 17.5%, 45% and 37.5% of fish farmers started carp farming respectively. Average 77.5% of farmers acquired training from NFEP project while 10% of them from government officials. There were 55% seasonal and 45% perennial ponds with average pond size 0.09 ha. After phase out of NFEP project, 92.5% of fish farmers followed polyculture systems, while only 7.5% of them followed monoculture ones. Farmers did not use any lime, organic and inorganic fertilizers in their ponds before association with NFEP project. They used lime, cow dung, urea and T.S.P during pond preparation at the rate of 247, 2562.68, 46.36 and 27.29 kg.ha-1.y-1 respectively where stocking density at the rate of 10,775 fry.ha-1 after phase out of the project. Feeding was at the rate of 3-5% body weight.fish-1.day-1. -

Improving Animal Productivity by Supplementary Feeding of Multinutrient Blocks, Controlling Internal Parasites and Enhancing Utilization of Alternate Feed Resources

IAEA-TECDOC-1495 Improving Animal Productivity by Supplementary Feeding of Multinutrient Blocks, Controlling Internal Parasites and Enhancing Utilization of Alternate Feed Resources A publication prepared under the framework of an RCA project with technical support of the Joint FAO/IAEA Programme of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture December 2006 IAEA-TECDOC-1495 Improving Animal Productivity by Supplementary Feeding of Multinutrient Blocks, Controlling Internal Parasites and Enhancing Utilization of Alternate Feed Resources A publication prepared under the framework of an RCA project with technical support of the Joint FAO/IAEA Programme of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture December 2006 The originating Section of this publication in the IAEA was: Animal Production and Health Section Joint FAO/IAEA Division International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramer Strasse 5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria IMPROVING ANIMAL PRODUCTIVITY BY SUPPLEMENTARY FEEDING OF MULTI-NUTRIENT BLOCKS, CONTROLLING INTERNAL PARASITES, AND ENHANCING UTILIZATION OF ALTERNATE FEED RESOURCES IAEA, VIENNA, 2006 IAEA-TECDOC-1495 ISBN 92–0–104506–9 ISSN 1011–4289 © IAEA, 2006 Printed by the IAEA in Austria December 2006 FOREWORD A major constraint to livestock production in developing countries is the scarcity and fluctuating quantity and quality of the year-round feed supply. Providing adequate good quality feed to livestock to raise and maintain their productivity is, and will continue to be, a major challenge to agricultural scientists and policy makers all over the world. The increase in population and rapid growth in world economies will lead to an enormous increase in demand for animal products, a large part of which will be from developing countries. -

SAU201501 21-09-03496 11.Pdf

A COMPARISON BETWEEN CONTRACT AND NON CONTRACT POTATO FARMERS DEBASHISH KAR DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION AND INFORMATION SYSTEM SHER-E-BANGLA AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY DHAKA-1207 JUNE, 2015 A COMPARISON BETWEEN CONTRACT AND NON CONTRACT POTATO FARMERS DEBASHISH KAR DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION AND INFORMATION SYSTEM SHER-E-BANGLA AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY DHAKA-1207 JUNE, 2015 A COMPARISON BETWEEN CONTRACT AND NON CONTRACT POTATO FARMERS BY DEBASHISH KAR REGISTRATION NO.: 09-03496 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Agriculture, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE (MS) IN AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SEMESTER: JAN-JUNE, 2015 Approved By: Kh. Zulfikar Hossain Prof. Dr. Md. Rafiquel Islam Supervisor Co- Supervisor & Dept. of Agricultural Extension and Assistant Professor Information System Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University Dept. of Agricultural Extension and Information System Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University Dr. M. M. Shofi Ullah Associate Professor & Chairman Examination Committee Dept. of Agricultural Extension and Information System Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University Dedicated to my Beloved parents and Gurudev DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION AND INFORMATION SYSTEM Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, A COMPARISON BETWEEN CONTRACT AND NON CONTRACT POTATO FARMERS submitted to the Faculty of Agriculture, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka-1207, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION, embodies the result of a piece of bonafide research work carried out by DEBASHISH KAR, Registration No.: 09-03496 under my supervision and guidance. -

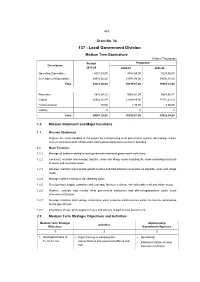

137 - Local Government Division

453 Grant No. 34 137 - Local Government Division Medium Term Expenditure (Taka in Thousands) Budget Projection Description 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 Operating Expenditure 4321,54,00 4753,69,00 5229,06,00 Development Expenditure 29919,66,00 31541,98,00 34696,18,00 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 Recurrent 7815,04,16 9003,87,04 8807,80,41 Capital 26425,35,84 27289,84,96 31115,37,59 Financial Asset 80,00 1,95,00 2,06,00 Liability 0 0 0 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 1.0 Mission Statement and Major Functions 1.1 Mission Statement Improve the living standard of the people by strengthening local government system, developing climate resilient rural and urban infrastructure and implementing socio-economic activities. 1.2 Major Functions 1.2.1 Manage all matters relating to local government and local government institutions; 1.2.2 Construct, maintain and manage Upazilla, union and village roads including the roads and bridges/culverts of towns and municipal areas; 1.2.3 Develop, maintain and manage growth centres and hats-bazaars connected via Upazilla, union and village roads; 1.2.4 Manage matters relating to safe drinking water; 1.2.5 Develop water supply, sanitation and sewerage facilities in climate risk vulnerable rural and urban areas; 1.2.6 Finance, evaluate and monitor local government institutions and offices/organizations under Local Government Division; 1.2.7 Develop, maintain and manage small-scale water resource infrastructures within the timeline determined by the government. 1.2.8 Enactment of Law, promulgation of rules and policies related to local government. -

Quality of Milk Available at Local Markets of Muktagacha Upazila in Mymensingh District

J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 11(1): 119–124, 2013 ISSN 1810-3030 Quality of milk available at local markets of Muktagacha upazila in Mymensingh district M. A. Islam*, M. H. Rashid, M. F. I. Kajal, and M. S. Alam Department of Dairy Science, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The present experiment was conducted to detect quality and level of the adulteration in milk collected from Dharchuni, Atani and Khamar bazar of Muktagacha Upazilla. Organoleptic parameters used to monitor the status of milk samples were color, flavor, taste, texture; physical parameter used was specific gravity; chemical parameters used were acidity, fat content, protein content, lactose content, ash, total solids, solids-not-fat; and the adulteration test used were starch test and formalin test. The tested milk samples showed significantly differences (p<0.05) for specific gravity, protein, fat, lactose and TS contents. No significant difference (p>0.05) were found for %acidity, ash content, and SNF content of milk samples. Milk collected from Khamar Bazar was higher for protein and fat contents than other markets. Adulteration tests, for all the samples were found negative. Although, there were some fluctuations among the parameters of milk samples regarding standard values; all of the milk samples were found to be acceptable. Keywords: Milk quality, Market, Adulteration Introduction Milk is defined as the whole, fresh, clean, lacteal secretion obtained by complete milking of one or more healthy animals excluding that obtained within fifteen days before or five days after calving or such periods as may be necessary to render milk practically colostrums free and containing the minimum prescribed percentage of milk fat (3.5%) and solids not fat (8.5%) (Goff and Hill, 1993). -

Determining the Magnesium Concentration from Some Indigenous Fruits and Vegetables of Chittagong Region, Bangladesh 1*Islam, F., 1Bhattacharjee, S

International Food Research Journal 21(4): 1413-1417 (2014) Journal homepage: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my Determining the magnesium concentration from some indigenous fruits and vegetables of Chittagong region, Bangladesh 1*Islam, F., 1Bhattacharjee, S. C., 2Khan, S. S. A. and 1Rahman, S. 1Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (BCSIR) Laboratories Chittagong, Chittagong- 4220, Bangladesh 2Asian University for Women, Chittagong-4100, Bangladesh Article history Abstract Received: 8 January 2014 Magnesium is an essential mineral for its crucial role in many physiological function and Received in revised form: metabolism. While magnesium should be present in nutritionally important quantities in regular 30 January 2014 Accepted: 31 January 2014 diets, average Bangladeshi diets frequently fail to contain an adequate supply of the element. Thus, the study aims to determine the amount of magnesium in four different dietary items, Keywords bananas, vegetables and pulses, locally available in Chittagong, Bangladesh, using Spectro- photometric method. As per the findings, the magnesium concentration for banana contrasts Magnesium Arum between 0.843 µg/g and 3.654µg/g. Musa cavendishii from Satkania Upazila contains the Banana highest value while, the lowest amount is found in Musa paradisiaca from Lama Upazila. For Vegetable and Pulse arums, the amount varies between 0.476 and 21.3456µg/g. The highest amount was found in arums, Colocasia esculenta (Patiya upazila) i.e. 21.3456µg/g and the lowest amount appears from the same species at Boailkhali upazila. In vegetables, the quantity fluctuates between 1.62 and 5.93 µg/g with the maximum amount found in Anowara upazila. Magnesium in pulses was observed in the range 6.5333-28.3208 µg/g. -

Upazila Election Monitoring Report-2014

Democracywatch Report on 4th Upazila Election Observation-2014 Democracywatch 15 Eskaton Garden Road Ramna, Dhaka – 1000. Tel: +8802 9344225-6, +8802 8315 807 Fax: 8802 9330405 E-mail: info@ dwatch-bd.org , Web: www.dwatch-bd.org Editorial Team: • Taleya Rehman, Executive Director • Feroze Nurun-Nabi Jugal, Program Coordinator • Rakibul Islam, Program Officer • Maria Akter, Program Assistant 15 June 2014 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Chapter Page Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Foreword 5 Introduction 6 Brief History of Upazila Election 6 Role of Election Commission Bangladesh 7 Law and Ordinance on Election 7 Objectives of Democracywatch Election Monitoring 8 Democracywatch Election Observation Plan 8 Observers Training 9 Election Day Observation 10 Counting Process 11 Print Media Report 12 Brief Description of Violence 12 Conclusion 14 Annexure 17 Annex-1 Summery of Democracywatch’s working area Annex-2 Summery of Observers Training Annex-3 Fact Sheet of 4 th Upazila Election 2014 3 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVATIONS: CBO- Community Based Organization CSO- Civil Society Organization DPPF- District Public Policy Forum DW- Democracywatch ECB - Election Commission Bangladesh EWG- Election Working Group LG - Local Government MDG- Millennium Development Goal MP- Member of Parliament NGO- Non Government Organization PNGO- Partner NGO PS- Polling Station RPO - Representation of the People Order STO - Short Term Observer TAF - The Asia Foundation UNO-Upazila Nirbahi Officer UP- Union Parishad UZP - Upazila Parishad 4 Foreword Democracywatch played an important role in the 4thUpazila Elections in Bangladesh which was held in 6 phases between 19 February and 19 May 2014. Although most of Democracywatch’s work concentrated on the Election Day itself, there were several activities to increase voter awareness toon the electoral process carried out with considerable success. -

Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: G Bio-Tech & Genetics

OnlineISSN:2249-4626 PrintISSN:0975-5896 DOI:10.17406/GJSFR SmallScaleFishFarmers FishProductionTechnology GrowthPromotersbyRhizospheric MicroorganismsonNaturalMedium VOLUME20ISSUE1VERSION1.0 Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: G Bio-Tech & Genetics Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: G Bio-Tech & Genetics Volume 20 Issue 1 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. © Global Journal of Science (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Frontier Research. 2020 . Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Open Scientific Standards All rights reserved. This is a special issue published in version 1.0 Publisher’s Headquarters office of “Global Journal of Science Frontier Research.” By Global Journals Inc. Global Journals ® Headquarters All articles are open access articles distributed 945th Concord Streets, under “Global Journal of Science Frontier Research” Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, Reading License, which permits restricted use. United States of America Entire contents are copyright by of “Global USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 Journal of Science Frontier Research” unless USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 otherwise noted on specific articles. No part of this publication may be reproduced Offset Typesetting or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including Glo bal Journals Incorporated photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, permission. Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom The opinions and statements made in this book are those of the authors concerned. Packaging & Continental Dispatching Ultraculture has not verified and neither confirms nor denies any of the foregoing and no warranty or fitness is implied. Global Journals Pvt Ltd E-3130 Sudama Nagar, Near Gopur Square, Engage with the contents herein at your own risk.