Elgar the Dream of Gerontius Sir Mark Elder Paul Groves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAN 10110 BOOK.Qxd 20/4/07 4:19 Pm Page 2

CHAN 10110 Front.qxd 20/4/07 4:19 pm Page 1 CHAN X10110 CHANDOS CLASSICS CHAN 10110 BOOK.qxd 20/4/07 4:19 pm Page 2 John Ireland (1879–1962) 1 Vexilla Regis (Hymn for Passion Sunday)* 11:54 2 Greater Love Hath No Man† 6:51 3 These Things Shall Be‡ 22:12 Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht 4 A London Overture 13:36 5 The Holy Boy (A Carol of the Nativity) 2:43 6 Epic March 9:13 TT 67:11 Paula Bott soprano*† Teresa Shaw contralto* James Oxley tenor* Bryn Terfel bass-baritone*†‡ Roderick Elms organ* London Symphony Chorus*†‡ John Ireland London Symphony Orchestra Richard Hickox 3 CHAN 10110 BOOK.qxd 20/4/07 4:19 pm Page 4 and Friday before Easter – and what we cannot sketch was ready during April. Ireland Ireland: Orchestral and Choral Works have – the ceremonies on the Saturday before remarked that he felt the words were ‘an Easter as practised by the Roman Church – expression of British national feeling at the something absolutely agelong & from present time’. In fact he had earlier made a John Nicholson Ireland was born near nineteen-year-old Ireland was then still a everlasting – the rekindling of Fire – Lumen quite different setting of these words for Manchester and spent most of his life in student of Stanford’s, and was assistant Christi. The Motherland Song Book published in London, though with interludes in the Channel organist at Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, 1919. The composer made a few adjustments Islands and Sussex. His was a life of restricted London. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Sir Mark Elder Leads CSO in Exploration of Literature's Influence

ChicagoPride.com News December 13, 2011 Sir Mark Elder leads CSO in exploration of literature's influence on music By GoPride.com News Staff December 13, 2011 https://chicago.gopride.com/news/article.cfm/articleid/24335776 CST actors also to perform scenes from selected plays, January 5-10, and 12-15 CHICAGO, IL -- British conductor Sir Mark Elder makes his return to Orchestra Hall for a two-week residency that explores the influence of Shakespeare and other works of literature on music and features actors from Chicago Shakespeare Theater (CST), under the direction of CST Artistic Director Barbara Gaines, bringing the Bard's words to life. Sir Mark Elder's first subscription week of concerts on January 5-10, is an all-Berlioz program, highlighted by the Queen Mab Scherzo and Romeo at the Tomb from the composer's Romeo and Juliet. Select readings from Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, performed by Brendan Marshall-Rashid and Susan Strunk from the Chicago Shakespeare Theater, precede these two works. British violist Lawrence Power also makes his CSO debut on these concerts and is featured in Berlioz's Harold in Italy, a work Paganini encouraged Berlioz to compose and was inspired by Lord Byron's poetry. Elder concludes his two-week winter residency January 12-15, with a further exploration into Shakespeare's influence on music through works by Delius, Elgar, Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky. Included on the program is Elgar's rarely performed orchestral work Falstaff, which portrays Shakespeare's Sir John Falstaff from Henry IV. Actor Greg Vinkler brings to life passages from Henry IV Parts 1 and 2. -

The Late Summer Newsletter

AUGUST 2020 Issue No: 17 Welcome to the late summer newsletter. AGM and the musical phrasing stand out, always with clear thought for the meaning. Furthermore, the perfect Please note that the AGM has been postponed to December velvety colouring of their basses, with no forcing of the 2020 – date/venue to follow in the next newsletter. As the Holst th lower register whatsoever, eases the tuning and Birthplace Trust annual concert scheduled for 19 September harmonic construction of the ensemble. Preece proves 2020 has been cancelled, so too must our AGM pencilled in for that Holst is more than The Planets. that afternoon. Hopefully, if concerts resume in the next three months, we could have our AGM in the afternoon of a Saturday Jerónimo Marin before Christmas with a concert in Cheltenham that evening. HOLST/ VAUGHAN WILLIAMS/ WALT WHITMAN SAVITRI Holst, Vaughan Williams and the poetry of Walt Holst’s one-act opera will be performed in the gardens of Whitman Lauderdale House, Highgate, London, with two performances each evening on August 13th, 15th, 20th and 22nd. The The poems of Walt Whitman, and in particular his production given by Hampstead Garden Opera will be staged Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855, soon inspired by Julia Mintzer and conducted by Thomas Payne (please visit new generations of English composers. These website at https://hgo.org.uk/savitri/ for further detail). included Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav von Holst. Vaughan Williams was introduced to Whitman’s PART SONGS BY HOLST poetry by Bertrand Russell in 1892, the year of the poet’s death. -

Myung-Whun Chung

如 • 歌 • 文 • 化 Ruge Artists Management 扫描关注微信订阅号 CONDUCTOR / Myung-Whun Chung PERFORMANCES He was Music Director of the Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1984 to 1990, Principal Guest Conductor of the TeatroComunale of Florence from 1987 to 1992, Music Director of the Opéra de Paris-Bastille from 1989 to 1994 and Principal Conductor atthe Santa Cecilia Orchestra in Rome from 1997 to 2005. In 1995, Myung-Whun Chung founds the Asia Philharmonic, an orchestra made up of the best musicians from 8 Asian countries. In 2005,he was appointed Music Director of the Seoul Philarmonic Orchestra. He has been Music Director of the Orchestre Philharmonique deRadio France since 2000. Myung-Whun Chung has conducted virtually all the world’s leading orchestras, including the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic, theConcertgebouw, all the major London and Parisian Orchestras, Filharmonica della Scala, Bayerisch Rundfunk, Dresden Staatskapelle,Boston and Chicago Symphony, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland and Philadelphia Orchestras. RECORDINGS An exclusive recording artist for Deutsche Grammophon since 1990, many of his numerous recordings have won international prizes and awards. These include Messiaen's TurangalîlaSymphony and Eclairs sur l’Au-Delà, Verdi's Otello, Berlioz'sSymphonie Fantastique, Shostakovich's Lady Macbeth with the Orchestre de l'Opéra Bastille; a series of Dvorák's symphonies and serenades with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and a series dedicated to the great sacred music with the Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, including the award-winning recording of Duruflé’s and Fauré’s Requiems with Cecilia Bartoli and Bryn Terfel. Recent releases include Messiaen’s La transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ and Des Canyons aux étoiles with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France as well as works by Debussy and Ravel with the Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra. -

Festival 2021

FESTIVAL 2021 leedslieder1 @LeedsLieder @leedsliederfestival #LLF21 LEEDS LIEDER has ‘ fully realised its potential and become an event of INTERNATIONAL STATURE. It attracts a large, loyal and knowledgeable audience, and not just from the locality’ Opera Now Ten Festivals and a Pandemic! In 2004 a group Our Young Artists will perform across the weekend of passionate, visionary song enthusiasts began and work with Dame Felicity Lott, James Gilchrist, programming recitals in Leeds and this venture has Anna Tilbrook, Sir Thomas Allen and Iain steadily grown to become the jam-packed season Burnside. Iain has also programmed a fascinating we now enjoy. With multiple artistic partners and music theatre piece for the opening lunchtime thousands of individuals attending our events recital. New talent is on evidence at every turn in every year, Leeds Lieder is a true cultural success this Festival. Ema Nikolovska and William Thomas story. 2020 was certainly a year of reacting nimbly return, and young instrumentalists join Mark and working in new paradigms. We turned Leeds Padmore for an evening presenting the complete Lieder into its own broadcaster and went digital. Canticles by Britten. I’m also thrilled to welcome It has been extremely rewarding to connect with Alice Coote in her Leeds Lieder début. A recital not audiences all over the world throughout the past 12 to miss. The peerless Graham Johnson appears with months, and to support artists both internationally one of his Songmakers’ Almanac programmes and known and just starting out. The support of our we welcome back Leeds Lieder favourites Roderick Friends and the generosity shown by our audiences Williams, Carolyn Sampson and James Gilchrist. -

ONYX4206.Pdf

EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) Sea Pictures Op.37 The Music Makers Op.69 (words by Alfred O’Shaughnessy) 1 Sea Slumber Song 5.13 (words by Roden Noel) 6 Introduction 3.19 2 In Haven (Capri) 1.52 7 We are the music makers 3.56 (words by Alice Elgar) 8 We, in the ages lying 3.59 3 Sabbath Morning at Sea 5.24 (words by Elizabeth Barrett Browning) 9 A breath of our inspiration 4.18 4 Where Corals Lie 3.43 10 They had no vision amazing 7.41 (words by Richard Garnett) 11 But we, with our dreaming 5 The Swimmer 5.50 and singing 3.27 (words by Adam Lindsay Gordon) 12 For we are afar with the dawning 2.25 Kathryn Rudge mezzo-soprano 13 All hail! we cry to Royal Liverpool Philharmonic the corners 9.11 Orchestra & Choir Vasily Petrenko Pomp & Circumstance 14 March No.1 Op.39/1 5.40 Total timing: 66.07 Artist biographies can be found at onyxclassics.com EDWARD ELGAR Nowadays any listener can make their own analysis as the Second Symphony, Violin Sea Pictures Op.37 · The Music Makers Op.69 Concerto and a brief quotation from The Apostles are subtly used by Elgar to point a few words in the text. Otherwise, the most powerful quotations are from The Dream On 5 October 1899, the first performance of Elgar’s song cycle Sea Pictures took place in of Gerontius, the Enigma Variations and his First Symphony. The orchestral introduction Norwich. With the exception of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, all the poets whose texts Elgar begins in F minor before the ‘Enigma’ theme emphasises, as Elgar explained to Newman, set in the works on this album would be considered obscure -

ARPCD 0403 Elgar

EDWARD ELGAR THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS JON VICKERS CONSTANCE SHACKLOCK MARIAN NOWAKOWSKI ORCHESTRA SINFONICA E CORO DI ROMA DELLA RAI SIR JOHN BARBIROLLI ROMA, 20.11.1957 ARCHIPEL DESERT ISLAND COLLECTION Edward Elgar (1857-1934) The Dream of Gerontius Op. 38 Oratorio for mezzo-soprano, tenor, bass, full choir and orchestra, based on the poem by Cardinal John Newman CD 1 74:54 CD 2 73:21 Part One Part Two (Cont.) [1] Prelude 10:27 [1] Thy judgment is now near (Angel, Soul of Gerontius) 3:26 [2] Jesu, Maria - I am near to death (Gerontius) 3:23 [2] Jesu! By that shuddering dread (Angel of Agony, Soul of Ger.) 6:07 [3] Kyrie eleison. Holy Mary, pray for him (Chorus) 2:34 [3] Praise to His Name! (Angel) 1:38 [4] Rouse thee, my fainting soul (Gerontius) 0:44 [4] Take me away (Soul of Gerontius) 3:38 [5] Be merciful, be gracious (Chorus) 3:29 [5] Lord, Thou hast been our refuge (Chorus) 1:11 [6] Sanctus fortis, Sanctus Deus (Gerontius) 5:10 [6] Softly and gently, dearly-ransomed soul (Angel, Chorus) 6:22 [7] I can no more (Gerontius) 2:00 [8] Rescue him, O Lord (Gerontius, Chorus) 2:27 [9] Novissima hora est (Gerontius) 1:31 [10] Profisciscere, anima Christiana (Priest) 1:45 BONUS: Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) [11] Go, in the name of Angels and Archangels (Chorus, Priest) 4:44 Symphonie fantastique Op. 14 Part Two [12] Prelude 1:57 [7] Rêveries - Passions 14:04 [13] I went to sleep (Soul of Gerontius) 4:11 [8] Un Bal 6:32 [14] My work is done (Angel, Soul of Gerontius) 8:53 [9] Scène aux Champs 16:04 [15] Low-born clods of brute earth (Chorus, Angel) 2:06 [10] Marche au supplice 4:36 [16] The mind bold and independent (Chorus) 2:37 [11] Songe d’une Nuit de Sabbat 9:38 [17] I see not those false spirits (Soul of Gerontius, Angel) 3:19 [18] Praise to the Holiest (Angel, Chorus) 3:28 The Hallé Orchestra [19] Glory to him (Chorus, Angel, Soul of Gerontius) 2:46 Sir John Barbirolli [20] Praise to the Holiest in the height (Chorus) 7:14 Recording: 02.01.1947. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Changing Cultural Paradigms in Choral Programming

Changing Cultural Paradigms in Choral Programming Ciara Anwen Cheli Advisor: Lisa Evelyn Graham, Music Wellesley College May 2020 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Music © Ciara Cheli, 2020 Cheli 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Part One: Reflecting on Our Past ................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One: An Overview of Choral Programming and Historical Trends ........................................... 7 Chapter Two: Modernism and a Choral Identity Crisis ......................................................................... 10 Chapter Three: Historical Perspectives on Concert Programming and Repertoire .............................. 15 Part Two: Looking To Our Future ................................................................................................ 19 Chapter One: Changing Cultures, Changing Choirs ............................................................................. 19 Chapter Two: Representation Matters .................................................................................................... 20 Chapter Three: Culturally Responsive Programming in the 21st Century .............................................. 24 Chapter Four: -

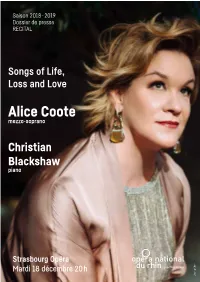

Alice Coote Mezzo-Soprano

Saison 2018 - 2019 Dossier de presse RECITAL Songs of Life, Loss and Love Alice Coote mezzo-soprano Christian Blackshaw piano Strasbourg Opéra Mardi 18 décembre 20 h du rhin opéra d'europe Jiyang Chen Jiyang Récital Alice Coote mezzo-soprano Christian Blackshaw piano “Songs of Life, Loss and Love...” n photo Jiyang Jiyang Che photo La mezzo-soprano Alice Coote, accompagnée au piano par Christian Blackshaw a intitulé son programme : « Songs of Life, Loss and Love ». Principalement consacré aux lieder des grands compositeurs du XIXe siècle : Johannes Brahms, Piotr Ilitch Tchaïkovski, Franz Schubert et Gustav Mahler, il sera aussi l’occasion d’entendre la Cantate de Haydn, dans laquelle Ariane se plaint de la fuite de Thésée. Un moment rare en perspective ! STRASBOURG, Opéra Ma 18 décembre 20 h Dossier de presse 2 Récital Alice Coote mezzo-soprano Christian Blackshaw piano “Songs of Life, Loss and Love...” Programme JOHANNES BRAHMS Vier Ernste Gesänge op. 121 PIOTR ILITCH TCHAIKOVSKY At the ball op. 38 n° 3 Death op. 57 n° 5 None but the lonely heart op. 6 n° 6 Why? op 6. n° 5 JOSEPH HAYDN Arianna a Naxos – Cantate Entracte FRANZ SCHUBERT Der Zwerg Das Tod und das Mädchen Du bist die Ruh Rastlose Liebe Abendstern D806 GUSTAV MAHLER Rückert Lieder Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder Liebst du um Schönheit Um Mitternacht Ich bin der Welt abhandengekommen Dossier de presse 3 Jiyang Chen Jiyang Alice Coote mezzo-soprano Alice Coote est considérée comme l’une des artistes les plus talentueuses de notre temps. -

Handel Arias

ALICE COOTE THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET HANDEL ARIAS HERCULES·ARIODANTE·ALCINA RADAMISTO·GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL A portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685–1749) 2 CONTENTS TRACK LISTING page 4 ENGLISH page 5 Sung texts and translation page 10 FRANÇAIS page 16 DEUTSCH Seite 20 3 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Radamisto HWV12a (1720) 1 Quando mai, spietata sorte Act 2 Scene 1 .................. [3'08] Alcina HWV34 (1735) 2 Mi lusinga il dolce affetto Act 2 Scene 3 .................... [7'45] 3 Verdi prati Act 2 Scene 12 ................................. [4'50] 4 Stà nell’Ircana Act 3 Scene 3 .............................. [6'00] Hercules HWV60 (1745) 5 There in myrtle shades reclined Act 1 Scene 2 ............. [3'55] 6 Cease, ruler of the day, to rise Act 2 Scene 6 ............... [5'35] 7 Where shall I fly? Act 3 Scene 3 ............................ [6'45] Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 (1724) 8 Cara speme, questo core Act 1 Scene 8 .................... [5'55] Ariodante HWV33 (1735) 9 Con l’ali di costanza Act 1 Scene 8 ......................... [5'42] bl Scherza infida! Act 2 Scene 3 ............................. [11'41] bm Dopo notte Act 3 Scene 9 .................................. [7'15] ALICE COOTE mezzo-soprano THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET conductor 4 Radamisto Handel diplomatically dedicated to King George) is an ‘Since the introduction of Italian operas here our men are adaptation, probably by the Royal Academy’s cellist/house grown insensibly more and more effeminate, and whereas poet Nicola Francesco Haym, of Domenico Lalli’s L’amor they used to go from a good comedy warmed by the fire of tirannico, o Zenobia, based in turn on the play L’amour love and a good tragedy fired with the spirit of glory, they sit tyrannique by Georges de Scudéry.