Chapter 8: Africans in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Possible Antecedents and Implications to African-Australians Participating in the Proposed Pilot Program of Settlement in Rural

‘African Renewal, African Renaissance’: New Perspectives on Africa’s Past and Africa’s Present. The African Studies Association of Australia and the Pacific (AFSAAP) Annual Conference 26-28 November 2004, University of Western Australia Possible Antecedents and Implications to African-Australians Participating in the Proposed Pilot Program of Settlement in Rural Victoria: A Study of Strategic Management of Service Delivery to an Emerging Community in Rural Areas: A Critical Review Dr. Apollo Nsubuga-Kyobe, La Trobe University Introduction and the Basis of the Study This paper has been influenced by both the work we did on African Communities and Settlement Services Delivery in Victoria, and my participation in a number of consultations. These have included: migration and humanitarian programs and the associated settlement issues principally on behalf of African-Australians, the majority are refugees and humanitarian entrants. Also, I have been involved with the Integrated Humanitarian Settlement Strategy, Population Debate, Reviewing the Review of Settlement Services, Economic Contribution of Victoria’s Culturally Diverse Population, Regional Settlement in Rural Victoria, the Victoria Racial Verification Act, Multicultural Victoria Act and How to deal with gambling and substance abuse mainly among youth. Given the foregoing, this paper assesses a number of fundamental issues connected with newly arrived Refugee and Humanitarian entrants, mainly those from Sub-Sahara Africa. It seeks to identify the issues likely to be confronted when settling in Victorian locations such as: Shepparton, Swan-Hill, Warrnambool, Mildura or Colac, to name a few of the nine proposed places. The paper also questions whether secondary settlement of the African Refugees and Humanitarian entrants would be an alternative and a strategic option to picking these new settlers straight from refugee camps overseas. -

1 African Transnational Diasporas: Theoretical Perspectives 2 Vintages and Patterns of Migration

Notes 1 African Transnational Diasporas: Theoretical Perspectives 1. In 1965 George Shepperson (1993), drawing parallels with the Jewish dias- pora, coined the term ‘African diaspora’. The term was also closely associ- ated with social and political struggles for independence in Africa and the Caribbean. For detailed examination on the origins of the term African dias- pora, see Manning (2003) and Zeleza (2010). 2. The Lebanese in West Africa, Indian Muslims in South Africa and the Hausa in West Africa and Sudan are some of the examples of African diasporas within the continent (Bakewell, 2008). 3. See, for example, Koser’s (2003) edited volume, New African Diasporas and Okpewho and Nzegwu’s (2009) edited volume, The New African Diaspora. Both books provide a wide range of case studies of contemporary African diasporas. 4. This taxonomy has been adapted and developed from my examination of Zimbabwean transnational diaspora politics (see Pasura, 2010b). 2 Vintages and Patterns of Migration 1. Ethnic differences between ZANU and ZAPU caused the war of liberation to be fought on two fronts until the formation of the Patriotic Front, a unified alliance. ZAPU continued to advocate for multi-ethnic mobilization; historians have sought to explain the growing regional/ethnic allegiance partly in terms of the role of the two liberation armies, as old ZAPU committees existed in the Midlands and Manicaland but the areas became ZANU after having received Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) freedom fighters. 2. The subtitle comes from the BBC’s (2005) article entitled: ‘So where are Zimbabweans going?’ 3. See the case of Mutumwa Mawere, who recently won his case against the state with regard to dual citizenship (Gonda, 2013). -

Finding Home Far Away from Home: Place Attachment, Place-Identity, Belonging and Resettlement Among African- Australians in Hobart

Finding home far away from home: place attachment, place-identity, belonging and resettlement among African- Australians in Hobart Kiros Hiruy BSc Agriculture, Animal Sciences Diploma, Dairy Science Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Management, School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania Hobart, March 2009 Declaration This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution, and to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. Signed Date - 02 March 2009 ii Abstract This thesis explores the resettlement experiences of former African refugees in Hobart. It provides insight into their lived experiences and conceptualises displacement, place attachment, identity, belonging, place making and resettlement in the life of a refugee. It argues that current discourse on refugees‟ resettlement in popular media, academia and among host communities lacks veracity, and offers an alternative view to enrich current knowledge and encourage further research and debate. In this study 26 people from five countries of origin (Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone and Sudan) shared their life experiences in focus group discussions and interviews. Refugee theories and literature in resettlement, place attachment, place identity, belonging and resettlement were also reviewed. To develop an account of the lived experiences of refugees and understanding of the ways in which they create places, negotiate identity and belonging in the resettlement process, phenomenology and discourse analysis are used. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States

Buffalo Law Review Volume 4 Number 2 Article 2 1-1-1955 A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States Zelman Cowan Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Zelman Cowan, A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States, 4 Buff. L. Rev. 155 (1955). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol4/iss2/2 This Leading Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARISON OF THE CONSTITUTIONS OF AUSTRALIA AND THE UNITED STATES * ZELMAN COWAN** The Commonwealth of Australia celebrated its fiftieth birth- day only three years ago. It came into existence in January 1901 under the terms of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, which was a statute of the United Kingdom Parliament. Its origin in a 1 British Act of Parliament did not mean that the driving force for the establishment of the federation came from outside Australia. During the last decade of the nineteenth cen- tury, there had been considerable activity in Australia in support of the federal movement. A national convention met at Sydney in 1891 and approved a draft constitution. After a lapse of some years, another convention met in 1897-8, successively in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. -

African Australian Communities Leadership Forum Preliminary Community Issues Paper

African Australian Communities Leadership Forum Preliminary Community Issues Paper September 2016 © The African Australian Communities Leadership Forum, Melbourne, Victoria Acknowledgments This community issues paper was prepared pro bono in consultation with the contributors listed in this document. The African Australian Communities Leadership Forum thanks all members, meeting attendees and stakeholders who contributed their knowledge, expertise and time towards the development of this paper. For further information or to contact the African Australian Communities Leadership Forum, please see the contacts page in this document. AACLF Issues Paper September 2016 1/28 Contents Executive Summary Page 3 Background Page 4 Introduction Page 6 Figure 1. Strategy at a glance Page 7 Develop a Clearinghouse Page 8 Improve Social Justice Outcomes Page 9 Support people facing additional barriers Page 11 Strengthening Families Page 12 Empowering Young People Page 13 Employment Page 17 Supporting Seniors Page 18 Governance Page 19 Summary Recommendations Page 20 Figure 2. Action Plan Page 21 Conclusion Page 22 Additional Reading Material Page 23 Contributors Page 26 Contacts Page 28 AACLF Issues Paper September 2016 2/28 Executive Summary issues, incarceration, gender and sexual “My vision is an orientation. Australia where 3. Empowering young people with a focus African Australians on mentoring, education, entrepreneurship, employment and leadership. are Australians” -Youth Attendee, April 2016 meeting. 4. Providing a link and co-ordination through an organised and appropriate The 2011 census estimated the number of governance structure to continue this work African born migrants in Victoria at 59,000 and liaise with key stakeholders. and ABS data estimates that there are about 380,000 African Australians nationally. -

Fitting in Or Falling Out? Australia's Place in the Asia-Pacific Regional

FITTING IN OR FALLING OUT? AUSTRALIA’S PLACE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL ECONOMY Mark Beeson alliance.ussc.edu.au October 2012 US STUDIES CENTRE | ALLIANCE 21 FITTING IN OR FALLING OUT? AUSTRALIA’S PLACE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGIONAL ECONOMY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ■■ At■the■centre■of■the■new■economic■and■political■realities■that■shape■the■Asia- Pacific■region■is■the■relationship■between■China■and■the■United■States,■Australia’s■ The Alliance 21 Program is a multi-year research initiative respective■principal■trade■partner■and■long-standing■security■guarantor. that examines the historically strong Australia-United ■■ Australia■needs■to■adapt■to■new■market■forces■in■the■international■ States relationship and works to address the challenges economy■in■order■to■escape■the■resource■curse. and opportunities ahead as the alliance evolves in a changing Asia. Based within the United States Studies ■ ■ Despite■the■changing■dynamics■of■the■region■and■the■potential■rivalries■that■may■ Centre at the University of Sydney, the program was exist,■Australia■must■ensure■its■national■interests■continue■to■be■advanced. launched by the Australian Prime Minister in 2011 as a public-private partnership to develop new insights and policy ideas. Australia is caught between two worlds. On one hand, it has the opportunity to take advantage of Asia’s rise and intergrate with Asian economies in order to guarantee its inclusion in the region’s rapid growth. On the other The Australian Government and corporate partners Boral, hand, it faces a series of challenges. Asian economies are developing with great speed and promise. Adapting Dow, News Corp Australia, and Northrop Grumman to changing market complementarity and escaping the resource-curse will be crucial to Australia ‘fitting in’. -

Adaptation of Arab Immigrants to Australia: Psychological, Social' Cultural and Educational Aspects

,l q o") 'no ADAPTATION OF ARAB IMMIGRANTS TO AUSTRALIA: PSYCHOLOGICAL, SOCIAL' CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL ASPECTS Nina Maadad,8.4., Dip. Ed., MBd. Studies Research Portfolio submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Bducation in the University of Adelaide, March 2007. ADDENDUM Table B (cont) Eclucational and Occupational Background of Respondents page 45b. ERRATA Page Line AMENDMENT 7 11 delete etc 10 13 l¡r should be lts 26 5 from that shouldbe thctn bottom 34 I4 group should be groups 53 6 from Add century afÍer nineteenth bottom 4 I Tuttisia should be Cairo 8 2 Insefi (Robinson, 1996) 19 1 Delete is and insert has an 2 Delete a 26 4 Delete of 28 2from Delete to the extent and delete lr bottom 70 9 suit case should be suitcase 98 4 there nationality should be their nationality 110 t7 ¿v¿r should be every t20 16 other shouldbe others 160 l7 than shouldbe then 161 t7 Arabian should be Arab r70 4 Arabian should be Arabic 1 9 1 4 from convent should be convert bottom 230 1 Abdullah, S. should be Saeed, A. 234 6 from Taric shouldbe Tarigh bottom TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract lv Declaration vt Äcknowledgements vll Dedication lx INTRODUCTION TO PORTFOLIO Introduction 2 Støtement of the Problem 4 Arabian Cultural Background 7 Arøbían Core Values 7 Islnm ínthe Arab World t4 Hístory of Druze Sect 22 Educatíon ìn the Arab World 26 Muslíms ín Australía 30 Druze ìn Australia 32 Theoretical Framework and Research Method Theoríes of ImmigraÍíon ønd Interactíon 33 Assumptions 38 Research MethodologY 38 S ele ctíon of -

Lesson 1. Introduction to Australia Purpose: to Introduce Students To

Lesson 1. Introduction to Australia Purpose: To introduce students to the continent of Australia. Standards: Goal 2, Standard 2 -To use English to achieve academically in all content areas: Students will use English to obtain, process, construct, and provide subject matter information in spoken and written form. Materials: - items to be put into a travel trunk [a billy (teapot), tea bags, cups, biscuits (crackers), pictures of Australian animals, etc…] - teapot and water - map or globe - construction paper - markers - musical cassette and/or video: Children’s Songs From Around The World (available at local libraries or department stores like Target) Procedures: 1. Before the lesson begins: a. Place the Australian items into the trunk. b. Make tickets to Australia out of construction paper (one for each student). Put a picture of a koala bear on each ticket and write students’ names on them. c. Place a large picture of a koala bear (or other pictures native to Australia) on the trunk. 2. Have students gather around the trunk. Let them guess where their destination might be. Pass out the tickets. 3. Explain that on this adventure, everyone will be a naturalist, (people who are interested in plants and animals around them). 4. Ask what children might know about Australia and record the information (KWL chart). 1 5. Find Australia on a map or globe. a. Identify Australia as a continent b. Look at all the different landscapes (mountains, valleys, rivers). c. Discuss and describe the terms: city, bush, outback, Great Barrier Reef. 6. Examine the trunk. a. Display animal pictures. b. -

African-Australian’ Identity in the Making: Analysing Its Imagery and 110 Explanatory Power in View of Young Africans in Australia Abay Gebrekidan

THE AUSTRALASIAN REVIEW OF AFRICAN STUDIES VOLUME 39 NUMBER 1 JUNE 2018 CONTENTS Editorial Decolonising African Studies – The Politics of Publishing 3 Tanya Lyons Articles Africa’s Past Invented to Serve Development’s Uncertain Future 13 Scott MacWilliam A Critique of Colonial Rule: A Response to Bruce Gilley 39 Martin A. Klein Curbing Inequality Through Decolonising Knowledge Production in Higher 53 Education in South Africa Leon Mwamba Tshimpaka “There is really discrimination everywhere”: Experiences and 81 consequences of Everyday Racism among the new black African diaspora in Australia Kwamena Kwansah-Aidoo and Virginia Mapedzahama ‘African-Australian’ Identity in the Making: Analysing its Imagery and 110 Explanatory Power in View of Young Africans in Australia Abay Gebrekidan Africa ‘Pretty Underdone’: 2017 Submissions to the DFAT White Paper 130 and Senate Inquiry Helen Ware and David Lucas Celebrating 40 Years of the Australasian Review of African Studies: A 144 Bibliography of Articles Tanya Lyons ARAS Vol.39 No.1 June 2018 1 Book Reviews 170 AIDS Doesn’t Show Its Face: Inequality, Morality and Social Change in Nigeria, by Daniel Jordan Smith Tass Holmes ARAS - Call for Papers 174 AFSAAP Annual Conference 2018 - Call for Papers 180 2 ARAS Vol.39 No.1 June 2018 Australasian Review of African Studies, 2018, 39(1), 110-129 AFSAAP http://afsaap.org.au/ARAS/2018-volume-39/ 2018 https://doi.org/10.22160/22035184/ARAS-2018-39-1/110-129 ‘African-Australian’ Identity in the Making: Analysing its Imagery and Explanatory Power in View of Young Africans in Australia1 Abay Gebrekidan School of Social Sciences and Humanities, La Trobe University2 [email protected] Abstract This article explores the term ‘African-Australian’, commonly used to describe Australians of African descent as a single homogeneous group. -

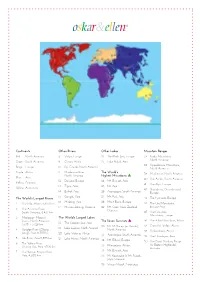

Other Rivers

Continents Other Rivers Other Lakes Mountain Ranges Red North America 8 Volga, Europe 22 The Black Sea, Europe 37 Rocky Mountains, North America Green South America 9 Congo, Africa 23 Lake Bajkal, Asia 38 Appalachian Mountains, Beige Europe 10 Rio Grande, North America North America Purple Africa 11 Mackenzie River, The World’s 39 Mackenzie, North America North America Highest Mountains s Blue Asia 40 The Andes, South America 12 Danube, Europe 24 Mt. Everest, Asia Yellow Oceania 41 The Alps, Europe 13 Tigris, Asia 25 K2, Asia White Antarctica 42 Skanderna, (Scandinavia) 14 Eufrat, Asia 26 Aconcagua, South America Europe 15 Ganges, Asia 27 Mt. Fuji, Asia The World’s Longest Rivers 43 The Pyrenees, Europe 16 Mekong, Asia 28 Mont Blanc, Europe 1 The Nile, Africa, 6,650 km 44 The Ural Mountains, 17 Murray-Darling, Oceania 29 Mt. Cook, New Zealand, Europe-Asia 2 The Amazon River, Oceania South America, 6,437 km 45 The Caucasus Mountains, Europe 3 Mississippi- Missouri The World’s Largest Lakes Rivers, North America, The Seven Summits s 46 The Atlas Mountains, Africa 3,778 + 3,726 km 18 The Caspian Sea, Asia 30 Mt. McKinley (or Denali), 47 Great Rift Valley, Africa 19 Lake Superior, North America 4 Yangtze River (Chang North America 48 Drakensberg, Africa Jiang), Asia, 6,300 km 20 Lake Victoria, Africa 31 Aconcagua, South America 49 The Himalayas, Asia 5 Ob River, Asia 5,570 km 21 Lake Huron, North America 32 Mt. Elbrus, Europe 50 The Great Dividing Range 6 The Yellow River 33 Kilimanjaro, Africa (or Eastern Highlands), (Huang Ho), Asia, 4,700 km Australia 7 The Yenisei-Angara River, 34 Mt.