Projecting an Endearing Combination of Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard-Hambleton-Catalog-1.Pdf

REFLECTIONS Now the sine qua non of mega-collectors and elite auction houses around the world, the once subversive “Street Art” that originated in New York City in the 1980s with such artists as Keith Haring and Jean Michel Basquiat has redefined where and how we look at art. Today, in the streets and in contemporary galleries, names such as Banksy, Stik and Shepard Fairey are familiar to hip, younger collectors. With fairs and festivals from New York to the Greek Islands and beyond, “Street Art” has become a global phenomenon. The wave of creativity that began to be noticed thirty-five years ago in New York’s East Village and brought renown to such ‘tags’ as “Samo,” “Crash,” “Daze” and “Lady Pink” was a fertile, drug fueled period of spray and splatter. Julian Schnabel had begun to make headlines for the upstart Mary Boone Gallery as Ronald Reagan became President and scientists raced to contain the spread of a mysterious and deadly new virus (HIV Aids). It was into this environment that Canadian artist Richard Hambleton arrived. Hambleton’s first stop in America was the west coast of the United States. He used funds from a grant to visit cities like Seattle and San Francisco, where he caused an uproar with his controversial “Mass Murder” series. The artist peppered the sidewalks with white chalk outlines of bodies – like those a police coroner sketches around the victim of a crime – the bloodier looking the better. The authorities were not amused. He was told also, that he was ineligible for future grant money by his donors. -

Frameworks for the Downtown Arts Scene

ACADEMIC REGISTRAR ROOM 261 DIVERSITY OF LONDON 3Ei’ ATE HOUSE v'Al i STREET LONDON WC1E7HU Strategy in Context: The Work and Practice of New York’s Downtown Artists in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s By Sharon Patricia Harper Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art at University College London 2003 1 UMI Number: U602573 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602573 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The rise of neo-conservatism defined the critical context of many appraisals of artistic work produced in downtown New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Although initial reviews of the scene were largely enthusiastic, subsequent assessments of artistic work from this period have been largely negative. Artists like Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf have been assessed primarily in terms of gentrification, commodification, and political commitment relying upon various theoretical assumptions about social processes. The conclusions reached have primarily centred upon the lack of resistance by these artists to post industrial capitalism in its various manifestations. -

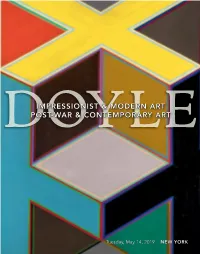

Doyle Auction House, “Richard Hambleton”

by Angelo Madrigale NEW YORK, NY -- His early years in New York brought about his To call artist Richard Hambleton famed Shadowman series, which became his best- mercurial would be a grand known work. Akin to the Image Mass Murder series, Hambleton’s Shadowmen were life-sized understatement. inky black abstract figures, placed strategically throughout downtown New York. Photographer Having passed away at age 65 just this past October, Hank O’ Neal deftly described them as “silhouettes Hambleton leaves behind a legacy of important of a nuclear blast,” the figures were imposing and work that would come to set the foundation for often frightening, lurking in alleyways, and even what we now call Street Art, though his personal confusing cabbies on the Bowery, mistakenly life was sadly marred with addiction and disease. thinking their splattered outstretched arms might Hailing from Vancouver, Hambleton made a stop be hailing a ride. Many coming out of CBGBs and in San Francisco before finally settling into the other late-night haunts found themselves victims of Lower East Side in 1979. What he brought with him the jump-scares Richard’s foreboding Shadowmen to New York was the beginning of a monumental caused. Hambleton’s need to create these figures body of work that was confrontational, challenging, en masse shared a compulsion with the growing and for many, overwhelmingly fascinating, with a graffiti scene coming out of the Bronx and other practice that encompassed illegal public art as well boroughs, which led to friendships with pioneering as a more traditional studio output. graffiti artists such as Chris “Daze” Ellis, who rented a studio space from Richard from 1983- Richard Hambleton’s early public work included 1988. -

Richard Hambleton Preface

A selection of my most recent writing for Munich’s Museum of Urban and Contemporary Art: Preface of our Richard Hambleton retrospective. Richard Hambleton is a foundational urban artist in more than one sense. The mysterious ferocity of this pioneering vandal’s interventions has set the tone for street art’s brazen approach since. His preference for anonymity in the appropriation of public space consciously marginalised his own identity as an artist; much of his elusive life was spent, quite literally, in the shadows. Both his themes and methods move along outer boundaries and reflect a figure well-acquainted with urban abyss. The liminal imagery of Hambleton’s mischievous street art conjures the very real darkness underlying mass spectacle; it generated feedback with a paranoia that, to this day, echoes across the public landscape. The warmth and enthusiasm with which collectors overseas contributed to our curation has enabled us to retrace the artist’s creative phases through a life that drifted between rockstardom and the void. Our retrospective encompasses the full range of Hambleton’s oeuvre, from 1983 to his death in 2017. His earliest public interventions, pretend crime scenes, spun into a performance that teased the limits of law, with Hambleton hanging up wanted posters that blurred into a murderous detective chasing himself. The victim outlines soon morphed from pavements onto city walls in his I Only Have Eyes for You series, ghost-like paste works that French street artist JR credits as an inspiration for his own renowned projects. The paper on which Hambleton printed his life-size likeness faded, leaving behind a pale trace – a white shadow. -

Parallel Tracks: Three Case Studies of the Relationship Between Street Art and U.S. Museums in the Twenty-First Century

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 11-2-2018 Parallel Tracks: Three Case Studies of the Relationship between Street Art and U.S. Museums in the Twenty-First Century Erin Rolfs Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Art Practice Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Rolfs, Erin, "Parallel Tracks: Three Case Studies of the Relationship between Street Art and U.S. Museums in the Twenty-First Century" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4835. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4835 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 11-2-2018 Parallel Tracks: Three Case Studies of the Relationship between Street Art and U.S. Museums in the Twenty-First Century Erin Rolfs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Art Practice Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons PARALLEL TRACKS THREE CASE STUDIES OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STREET ART AND U.S. MUSEUMS IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Erin Rolfs B.A., Louisiana State University, 2006 December 2018 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Woodward Gallery Established 1994

Woodward Gallery Established 1994 Richard Hambleton 1954 Born Vancouver, Canada. 1975 BFA, Painting and Art History at the Emily Carr School of Art, Vancouver, BC 1975-80 Founder and Co-Director “Pumps” Center for Alternative Art, Gallery, Performance and Video Space; Vancouver, BC; The Furies: Western Canada’s first punk band played their first gig at Richard Hambleton’s Solo Exhibition, May, 1976. Lives and works in New York City’s Lower East Side. SOLO EXHIBITION S 2013 “Beautiful Paintings,” Art Gallery at the Rockefeller State Park Preserve, Sleepy Hollow, NY 2011 “Richard Hambleton: A Retrospective,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Phillips de Pury and Giorgio Armani at Phillips de Pury & Company, New York 2010 “Richard Hambleton New York, The Godfather of Street Art,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Giorgio Armani at The Dairy, London “Richard Hambleton New York,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Giorgio Armani at the State Museum of Modern Art of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow “Richard Hambleton New York,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Giorgio Armani, Milan “Richard Hambleton New York,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Giorgio Armani, amFAR Annual Benefit, May 20, 2010 2009 “Richard Hambleton New York,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with -

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART Tuesday, May 14, 2019 NEW YORK IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART AUCTION Tuesday, May 14, 2019 at 11am POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART AUCTION Tuesday, May 14, 2019 at 2pm EXHIBITION Saturday, May 11, 10am – 5pm Sunday, May 12, Noon – 5pm Monday, May 13, 10am – 6pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART 1001-1072 John Bocchieri, New York Frances "Peggy" Brooks POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 2001-2079 Claire Chasanoff Post-War 2001-2042 David Follett Contemporary Art 2043-2079 A Gentleman, Park Avenue and Southampton, New York Robin Gottlieb Peter Mayer Glossary I A Palm Beach Heiress Conditions of Sale II Joan Harmon Van Metre, The Plains, VA Terms of Guarantee III Elisabeth B. Vondracek Information on Sales & Use Tax IV Buying at Doyle V Selling at Doyle VII Auction Schedule VIII Company Directory IX INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM Absentee Bid Form XI Formerly in the inventory of Berry-Hill Galleries, New York A Connecticut Private Collection The Gertrude D. Davis Trust A Private New Jersey Collection A New York Collector Two New York Gentlemen A North Carolina Collector The Collection of Faith Stewart-Gordon Lot 1009 1001 1001 1002 David James Attributed to Arthur J. Elsley British, 1853-1904 Playing with Fire, circa 1897 A Northeaster, The Coast of Devon, 1889 Remnants of a signature and date A.J. ELSLEY 18...7 (ll) Signed and dated D. James 89 (lr); Oil on canvas inscribed as titled on the reverse 19 3/4 x 26 inches (50.1 x 66 cm) Oil on canvas C 25 x 50 1/8 inches (63.5 x 127.3 cm) $10,000-20,000 C $10,000-15,000 1003 Johann Jan Zoetelief Tromp Dutch, 1872-1947 With Grandfather Signed J. -

VLADIMIR RESTOIN ROITFELD and ANDY VALMORBIDA in COLLABORATION with PHILLIPS De PURY & COMPANY and GIORGIO ARMANI PRESENT RICHARD HAMBLETON: a RETROSPECTIVE

VLADIMIR RESTOIN ROITFELD AND ANDY VALMORBIDA IN COLLABORATION WITH PHILLIPS de PURY & COMPANY AND GIORGIO ARMANI PRESENT RICHARD HAMBLETON: A RETROSPECTIVE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE New York, September 9, 2011 - Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld and Andy Valmorbida are proud to announce Richard Hambleton: A Retrospective, a survey of selected historical works from the legendary painter. Presented in collaboration with Giorgio Armani, the exhibition will be on show at Phillips de Pury & Company, located at 450 Park Avenue, New York City. The opening reception will take place on Friday, September 9, 2011, from 6 PM to 9 PM. This exhibition will be the final installment of an international series curated by Roitfeld and Valmorbida in collaboration with Giorgio Armani, which has included solo shows in New York, Milan, Cannes, Moscow, and London. Richard Hambleton: A Retrospective will highlight 50 of Hambleton’s most influential works spanning from 1982 to the present, as well as twenty iconic images of the artist’s work chronicled by photographer Hank O’Neal. A new catalogue will accompany the exhibition, featuring an essay by Christian Viveros-Faune. From his “Mass Murder” installations of the late 1970s, in which he secretly placed blood-splattered, chalk- body outlines throughout 15 cities, to his “Shadowman” series of the 1980s, where ominous, shadowy figures were painted in unexpected corners, alleys, and side streets, Richard Hambleton has permeated our collective consciousness with unforgettable images for over three decades. One of the only surviving members of a peer group that included Warhol, Basquiat, and Haring, Hambleton has been living a reclusive life in his Lower East Side studio for the past twenty years. -

Mauerkunst, Lebenskunst: an Anlysis of the Art on the Berlin Wall Magdalene A

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2007 Mauerkunst, Lebenskunst: An Anlysis of the Art on the Berlin Wall Magdalene A. Brooke Scripps College Recommended Citation Brooke, Magdalene A., "Mauerkunst, Lebenskunst: An Anlysis of the Art on the Berlin Wall" (2007). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 4. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/4 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “MAUERKUNST, LEBENSKUNST”: AN ANLYSIS OF THE ART ON THE BERLIN WALL BY MAGDALENE A. BROOKE SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR KATZ PROFESSOR RINDISBACHER April 20, 2007 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter One: Background, history of the Berlin Wall Chapter Two: Defining the Art on the Berlin Wall Chapter Three: Formal Aspects Berlin Wall Art Chapter Four: The Berlin Wall as a Space for Public Art Photographic Appendix Conclusion Bibliography Introduction On August 13, 1961 East German soldiers stretched roles of barbed wire through the heart of Berlin, encircling the Western zones. This rather drastic measure was the latest it a long series of temporary solutions to the problem of German identity. Located in middle Europe, Germany had, in its various forms, been caught in clashes between opposing sides of the continent for much of its history. During the Cold War it became, once again, a battlefield in a war between East and West. -

Exhibition Brochure

MAINSTREETERS: Taking Advantage, 1972–1982 January 9 – March 14, 2015 | Satellite Gallery Josh Baer, Deborah Fong, Annastacia McDonald, Jeanette Reinhardt and Carol Hackett at White Columns, New York City, tour de ‘4’, 1980, Courtesy of Paul Wong Cover: Mainstreeters: Annastacia McDonald, Deborah Fong, Paul Wong, Kenneth Fletcher at “The Complex” (26th and Main), c. 1974, Courtesy of Kazumi Tanaka This exhibition surveys the activities of a group of artists and creative practitioners who lived along Vancouver’s Main Street, the traditional dividing line between the city’s working-class multicultural east side and its more affluent anglocentric west side. Based on a foundation of childhood friendships and shared residences, the “Mainstreeters,” as they were known, took up art on their own terms and on their own turf, drawing the art world into their East Vancouver orbit as they explored and contributed to the city’s larger cultural ecology. The exhibition traces the evolution of a gang whose core formed at Vancouver’s Charles Tupper Secondary in 1968, when Kenneth Fletcher, Deborah Fong, Jeanette Reinhardt and Paul Wong entered eighth grade. Meetings with older students Annastacia McDonald and Charles Rea soon followed, as did the arrival of Marlene MacGregor from Toronto and Carol Hackett, who attended high school in Vancouver’s West End. The Mainstreeters eschewed formal art education for learn-as-you-go, hands-on experience. While still in high school, they participated in large-scale community arts events, taking advantage of exploratory workshops in video, both as students and as teachers. Like the “digital natives” of today, the Mainstreeters travelled the city with cameras, recording their findings, stagings, arguments and experiments. -

Franc Palaia Tel 7 Fax 201-420-8014

FRANC PALAIA Tel /Fax- 845-486-1378 Cell - 845-505-3123 21 Beechwood Park Poughkeepsie, NY 12601 - USA [email protected] 371 Fourth St. Jersey City, NJ 07302 - (studio ) www.francpalaia.com ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS & INSTALLATIONS- (SELECTED): 2011- Artist’s Project-Art Fair- Pier 92, New York, NY 2011 Samuel Morse Museum, Poughkeepsie, NY, “Points of View”, Photographs 2010- Queens College, John Calandra-Italian-American Institute, NYC “Dgital Polaroids” catalog 2010- G.A.S. Visual Art & Performance Space, .”100 Photographs” 2008- G.A.S. Visual Art & PerformanceSpace, Poughkeepsie, NY, “Mysterious Traveler” 2007- bau-beacon artist union, Beacon, NY, “Big Pictures” 2006 bau-beacon artist union, bau 24 , Beacon, NY , “Illuminated Polaroids” 2003- Vassar College,Poughkeepsie, NY Illuminated Landscapes, Photo-installation 2000- ArtWorks Space, Trenton, NJ , “Waterfall”, illuminated Photo- installation 1998- Velan Arte Contemporanea, Torino, Italy, installation, Illuminated Photo- Sculpture 1997- Lynn Goode Gallery, Houston, TX. Aqueducts & Viaducts, II 1995- O.K.Harris Works of Art, NYC, Aqueducts and Viaducts, Illuminated photo works 1995- Whitney Museum Annex., NYC, Window installation, Photo-lamps and sculpture 1994- Erica Hartman Gallery, La Jolla, CA., Photo-Sculpture 1994- New Jersey City University, NJ, In a Political Light, installation 1993- Broadway Windows, NYC, Photo-Illuminations 1993- New Jersey State Museum, NJ, catalog,Photo-Sculptural-Illumination 1993- Barneys New York, NY, Photo-Lamps and Photo-Sculpture 6 window installation -

Involuntarily) Shared Walls

16 NUART JOURNAL 2021 VOLUME 3 NUMBER 1 16–21 (INVOLUNTARILY) SHARED WALLS: Figure 1. Chalk tags. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring. New York City, USA, HARING'S ca. 1981 [first half of the year]. Photograph ©Klaus Wittmann. ILLEGAL STREET INTERACTIONS WITH BASQUIAT, HAMBLETON, Ulrich Blanché Heidelberg University, Germany WOJNAROWICZ, AND VALLAURI IN EARLY 1980s NYC (INVOLUNTARILY) SHARED WALLS 17 INTRODUCTION rather two pictorial signatures side by side, since apart Although street art and style writing graffiti in the from the (possibly) shared work equipment and the shared early 1980s was much less often documented than in 2020, wall, no obvious interaction between the two iconic images illegal street works by big names such as Keith Haring is discernible. This is not unusual for graffiti writers, who (1958–90), Richard Hambleton (1952–2017), or Jean-Michel often work at the same time, that is to say, side by side rather Basquiat (1960–88) were photographed and published quite than really together. frequently in mass media already in the '80s, even though Most representations of this shared wall are in- this concerned only a fraction of their work. complete. The best available representation of this shared Like Hambleton, Haring rarely documented his own wall was photographed by Klaus Wittmann (Figure 1) as street works. Both had photographers who photographed the construction fence stealer cut off Basquiat's car. This their works anyway – people who had gotten their permission shared wall is dated to 1981 (Deitch et al., 2008: 101). Reasons to take pictures and who they supplied with information for that might be that Basquiat was no longer active under before or after creating an artwork.1 As opposed to the the name SAMO, which he was until early 1980 (Goldstein, case of Hambleton, hardly any of Haring's illegal works 2017) and already when Haring met him around 1979 (Gruen, were photographed more than once.