Frameworks for the Downtown Arts Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Richard-Hambleton-Catalog-1.Pdf

REFLECTIONS Now the sine qua non of mega-collectors and elite auction houses around the world, the once subversive “Street Art” that originated in New York City in the 1980s with such artists as Keith Haring and Jean Michel Basquiat has redefined where and how we look at art. Today, in the streets and in contemporary galleries, names such as Banksy, Stik and Shepard Fairey are familiar to hip, younger collectors. With fairs and festivals from New York to the Greek Islands and beyond, “Street Art” has become a global phenomenon. The wave of creativity that began to be noticed thirty-five years ago in New York’s East Village and brought renown to such ‘tags’ as “Samo,” “Crash,” “Daze” and “Lady Pink” was a fertile, drug fueled period of spray and splatter. Julian Schnabel had begun to make headlines for the upstart Mary Boone Gallery as Ronald Reagan became President and scientists raced to contain the spread of a mysterious and deadly new virus (HIV Aids). It was into this environment that Canadian artist Richard Hambleton arrived. Hambleton’s first stop in America was the west coast of the United States. He used funds from a grant to visit cities like Seattle and San Francisco, where he caused an uproar with his controversial “Mass Murder” series. The artist peppered the sidewalks with white chalk outlines of bodies – like those a police coroner sketches around the victim of a crime – the bloodier looking the better. The authorities were not amused. He was told also, that he was ineligible for future grant money by his donors. -

The Death of Postfeminism : Oprah and the Riot Grrrls Talk Back By

The death of postfeminism : Oprah and the Riot Grrrls talk back by Cathy Sue Copenhagen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Montana State University © Copyright by Cathy Sue Copenhagen (2002) Abstract: This paper addresses the ways feminism operates in two female literary communities: the televised Oprah Winfrey talk show and book club and the Riot Grrrl zine movement. Both communities are analyzed as ideological responses of women and girls to consumerism, media conglomeration, mainstream appropriation of movements, and postmodern "postfeminist" cultural fragmentation. The far-reaching "Oprah" effect on modem publishing is critiqued, as well as the controversies and contradictions of the effect. Oprah is analyzed as a divided text operating in a late capitalist culture with third wave feminist tactics. The Riot Grrrl movement is discussed as the potential beginning of a fourth wave of feminism. The Grrrls redefine feminism and femininity in their music and writings in zines. The two sites are important to study as they are mainly populated by under represented segments of "postfeminist" society: middle aged women and young girls. THE DEATH OF "POSTFEMINISM": OPRAH AND THE RIOT GRRRLS TALK BACK by Cathy Sue Copenhagen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, MT May 2002 ii , ^ 04 APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Cathy Sue Copenhagen This thesis has been read by each member of a thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English Usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the College of Graduate Studies. -

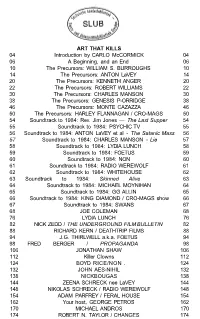

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

YOU KILLED ME FIRST the Cinema of Transgression Press Release

YOU KILLED ME FIRST The Cinema of Transgression Press Release February 19 – April 9, 2012 Opening: Saturday, February 18, 2012, 5–10 pm Press Preview: Friday, February 17, 2012, 11 am Karen Finley, Tessa Hughes-Freeland, Richard Kern, Lung Leg, Lydia Lunch, Kembra Pfahler, Casandra Stark, Tommy Turner, David Wojnarowicz, Nick Zedd “Basically, in one sentence, give us the definition of the ‚Cinema of Transgression’.” Nick Zedd: “Fuck you.” In the 1980s a group of filmmakers emerged from the Lower East Side, New York, whose shared aims Nick Zedd later postulated in the Cinema of Transgression manifesto: „We propose … that any film which doesn’t shock isn’t worth looking at. … We propose to go beyond all limits set or prescribed by taste, morality or any other traditional value system shackling the minds of men. … There will be blood, shame, pain and ecstasy, the likes of which no one has yet imagined.“ While the Reagan government mainly focused on counteracting the decline of traditional family values, the filmmakers went on a collision course with the conventions of American society by dealing with life in the Lower East Side defined by criminality, brutality, drugs, AIDS, sex, and excess. Nightmarish scenarios of violence, dramatic states of mind, and perverse sexual abysses – sometimes shot with stolen camera equipment, the low budget films, which were consciously aimed at shock, provocation, and confrontation, bear witness to an extraordinary radicality. The films stridently analyze a reality of social hardship met with sociopolitical indifference. Although all the filmmakers of the Cinema of Transgression shared a belief in a radical form of moral and aesthetic transgression the films themselves emerged from an individual inner necessity; thus following a very personal visual sense and demonstratively subjective readings of various living realities. -

Doyle Auction House, “Richard Hambleton”

by Angelo Madrigale NEW YORK, NY -- His early years in New York brought about his To call artist Richard Hambleton famed Shadowman series, which became his best- mercurial would be a grand known work. Akin to the Image Mass Murder series, Hambleton’s Shadowmen were life-sized understatement. inky black abstract figures, placed strategically throughout downtown New York. Photographer Having passed away at age 65 just this past October, Hank O’ Neal deftly described them as “silhouettes Hambleton leaves behind a legacy of important of a nuclear blast,” the figures were imposing and work that would come to set the foundation for often frightening, lurking in alleyways, and even what we now call Street Art, though his personal confusing cabbies on the Bowery, mistakenly life was sadly marred with addiction and disease. thinking their splattered outstretched arms might Hailing from Vancouver, Hambleton made a stop be hailing a ride. Many coming out of CBGBs and in San Francisco before finally settling into the other late-night haunts found themselves victims of Lower East Side in 1979. What he brought with him the jump-scares Richard’s foreboding Shadowmen to New York was the beginning of a monumental caused. Hambleton’s need to create these figures body of work that was confrontational, challenging, en masse shared a compulsion with the growing and for many, overwhelmingly fascinating, with a graffiti scene coming out of the Bronx and other practice that encompassed illegal public art as well boroughs, which led to friendships with pioneering as a more traditional studio output. graffiti artists such as Chris “Daze” Ellis, who rented a studio space from Richard from 1983- Richard Hambleton’s early public work included 1988. -

Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, No

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Peter R. Kalb, review of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11870. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation Curated by: Liz Munsell, The Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, and Greg Tate Exhibition schedule: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, October 18, 2020–July 25, 2021 Exhibition catalogue: Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, eds., Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020. 199 pp.; 134 color illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780878468713) Reviewed by: Peter R. Kalb, Cynthia L. and Theodore S. Berenson Chair of Contemporary Art, Department of Fine Arts, Brandeis University It may be argued that no artist has carried more weight for the art world’s reckoning with racial politics than Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988). In the 1980s and 1990s, his work was enlisted to reflect on the Black experience and art history; in the 2000 and 2010s his work diversified, often single-handedly, galleries, museums, and art history surveys. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation attempts to share in these tasks. Basquiat’s artwork first appeared in lower Manhattan in exhibitions that poet and critic Rene Ricard explained, “made us accustomed to looking at art in a group, so much so that an exhibit of an individual’s work seems almost antisocial.”1 The earliest efforts to historicize the East Village art world shared this spirit of sociability. -

Richard Hambleton Preface

A selection of my most recent writing for Munich’s Museum of Urban and Contemporary Art: Preface of our Richard Hambleton retrospective. Richard Hambleton is a foundational urban artist in more than one sense. The mysterious ferocity of this pioneering vandal’s interventions has set the tone for street art’s brazen approach since. His preference for anonymity in the appropriation of public space consciously marginalised his own identity as an artist; much of his elusive life was spent, quite literally, in the shadows. Both his themes and methods move along outer boundaries and reflect a figure well-acquainted with urban abyss. The liminal imagery of Hambleton’s mischievous street art conjures the very real darkness underlying mass spectacle; it generated feedback with a paranoia that, to this day, echoes across the public landscape. The warmth and enthusiasm with which collectors overseas contributed to our curation has enabled us to retrace the artist’s creative phases through a life that drifted between rockstardom and the void. Our retrospective encompasses the full range of Hambleton’s oeuvre, from 1983 to his death in 2017. His earliest public interventions, pretend crime scenes, spun into a performance that teased the limits of law, with Hambleton hanging up wanted posters that blurred into a murderous detective chasing himself. The victim outlines soon morphed from pavements onto city walls in his I Only Have Eyes for You series, ghost-like paste works that French street artist JR credits as an inspiration for his own renowned projects. The paper on which Hambleton printed his life-size likeness faded, leaving behind a pale trace – a white shadow. -

Nawang Khechog the Great Arya Tara Tibetan Meditation Music 5:11

Playlists by David Ruekberg Dance to Awaken the Heart, Rochester, NY #27: January 28, 2017 Artist Song Title Album Length Nawang Khechog The Great Arya Tara Tibetan Meditation Music 5:11 Maneesh de Moor Morning Praise Om Deeksha 8:54 Ernst Reijseger Homo Spiritualis Cave Of Forgotten Dreams (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) 2:21 Hukwe Zawose Nhongolo The Essential Guide To Africa 8:54 Dead Can Dance Nierika Memento 5:46 Deva Premal Guru Rinpoche Mantra Deva Lounge 7:23 Balligomingo Purify Absolute More Relaxed [Disc 2] 4:13 Manu Dibango Bessoka (Version Courte) The Essential Guide To Africa 3:28 Miriam Makeba Pata Pata 2000 Homeland 3:49 Thievery Corporation The Lagos Communique African Groove 3:55 Christina Aguilera featuring Steve Winwood Makes Me Wanna Pray Back To Basics 4:11 The Beatles Tomorrow Never Knows (Remastered) Revolver (Remastered) 2:59 Brian Eno & Rick Holland Glitch Drums Between The Bells 2:58 Sean Dinsmore Mangalam (Chillums at Dawn Remix) Dakini Lounge: Prem Joshua Remixed 6:00 India.Arie Slow Down Voyage To India 3:53 Jai Uttal Guru Bramha Shiva Station (Bonus Edition) 4:24 Bon Iver Lisbon, OH Bon Iver 1:34 Ulrich Schnauss Amaris Passage 5:20 David Ruekberg Silence_5s.mp3 Silence 0:05 Itzhak Perlman Bach: Violin Partita #2 In D Minor, BWV 1004 - 3. Sarabanda Bach: Sonatas & Partitas For Solo Violin [Disc 2] 3:52 Anoushka Shankar Ancient Love Rise 11:08 Ray Lynch Her Knees Deep In Your Mind Conversations With God 6:19 Soloists of the Ensemble Nipponia [Shakuhachi, Shamisen, Biwa, EsashiKoto] Oiwake ("Esashi Pack-horseman's -

Arias with a Twist Created Byjoey Arias Andbasil Twist

Johnnie Moore (Associate Producer) recently was Alex in I Love A Piano, an Irving Berlin Revue, one of The J-Men in Yehuda Duenyas’ One Million Forgotten Moments in Manhattan, the Narrator in Amoveo (a new dance work choreographed by Benjamin Millepied set to Philip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach at the Palais Garnier in Paris and conducted by Nico Muhly); Captain von Trapp in Doug Elkins’ restaging of The Sound of Music at Joe’s Pub@The Public; and Mather in Michael Portnoy’s The K Sound at the Kitchen. He is involved with Gotham Chamber Opera (Founding Board Member), Tandem Otter Productions (Chairman), and New York Theater Workshop (Usual Suspect). He is proud to have been the producer of Basil Twist’s Symphonie Fantastique in San Francisco in 1999. Johnnie is currently at work on a number of projects, including The J-Men (with Jason MacMahon), and Fspamaninye (Russian Remembrance). His Banana Bread Rules! ARIAS WITH A TWIST CREATED BY JOEY ARIAS AND BASIL TWIST November 18–21, 2009 | 8:30 pm November 24–25, 2009 | 8:30 pm November 27–28, 2009 | 8:30 pm November 22 and 29, 2009 | 7:00 pm December 2–5, 2009 | 8:30 pm December 9–12, 2009 | 8:30 pm December 6 and 13, 2009 | 7:00 pm presented by REDCAT Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater California Institute of the Arts ARIAS WITH A TWIST Neelam Vaswani (Production Stage Manager) Previous work with Basil Twist include Master CREATED BY JOEY ARIAS AND BASIL TWIST Peter’s Puppet Show (Disney Concert Hall, LA), ASM: La Bella (Spoleto, Lincoln Center); NY Credits: PSM: Voice 4 Vision Puppet Festival (4 yrs, TFNC), Song for New York (Mabou Mines); starring Joey Arias Ghosts (Juilliard School), Peter & Wendy (Arena Stage, Mabou Mines); The Adventures of with Charcoal Boy (TFNC and HERE) Uncle Vanya (Juilliard School); ASM: The Beard of Avon Eli Presser (NYTW), Don Juan (TFNA), and La Cenerentola, Venice (Juilliard School). -

Hip Hop: the Illustrated History of Break Dancing, Rap Music, and Graffiti, 0312373171, 9780312373177, Steven Hager, 112 Pages, St

Hip Hop: The Illustrated History of Break Dancing, Rap Music, and Graffiti, 0312373171, 9780312373177, Steven Hager, 112 pages, St. Martin's Press, 1984, 1984 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/17K01ga http://goo.gl/R4Iqv http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?store=book&keyword=Hip+Hop%3A+The+Illustrated+History+of+Break+Dancing%2C+Rap+Music%2C+and+Graffiti Examines the development in New York City of a Black culture centered around break dancing, graffiti art, and rap songs DOWNLOAD http://u.to/kVgNpT http://scribd.com/doc/27051546/Hip-Hop-The-Illustrated-History-of-Break-Dancing-Rap-Music-and-Graffiti http://bit.ly/1rEMhtI Fires in the Mirror Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and Other Identities, Anna Deavere Smith, Jan 1, 1997, Drama, 141 pages. Presents theatrical monologues based on interviews with participants and observers of the 1991 racial riots in New York's Crown Heights.. The Rap Attack African Jive to New York Hip Hop, David Toop, 1984, Music, 168 pages. The Baby-Sitters Club The Movie, A. L. Singer, Ann M. Martin, 1995, Juvenile Fiction, 32 pages. The Baby-sitters club decides to run a day camp during the summer, but faces unexpected problems.. Hip Hop Family Tree, Volume 1 , , 2013, Comics & Graphic Novels, 112 pages. Captures the history of the formative years of hip-hop, including such rap pioneers as Afrika Bambaataa, MC Sha Rock, and DJ Kool Herc.. Breaking and the New York City Breakers , Michael Holman, 1984, Performing Arts, 176 pages. Traces the history of break dancing, demonstrates basic dance moves, and offers profiles of top New York break dancers. -

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ (1954–1992) B

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ (1954–1992) b. 1954, Red Bank, NJ d. 1992, New York, NY SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 I is Someone Else, Morán Morán, Los Angeles CA David Wojnarowicz, Photography & Film, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC 2019 History Keeps Me Awake at Night, Museum Reina Sofia, Madrid David Wojnarowicz, Photography & Film, Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2018 History Keeps Me Awake at Night, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY Soon All This Will be Picturesque Ruins: The Installations of David Wojnarowicz, P·P·O·W, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: Video and Photography, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany. David Wojnarowicz: Flesh of My Flesh, Iceberg Projects, Chicago, IL 2016 Raging Through: The Art of David Wojnarowicz, Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 2011 Spirituality, P·P·O·W, New York, NY 2009 David Wojnarowicz, Supportico Lopez, Berlin, Germany 2006 Rimbaud in New York, CABINET, London, England David Wojnarowicz, Between Bridges, London, England 2004 Out of Silence: Artworks with Original Text by David Wojnarowicz, P·P·O·W, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: Rimbaud in New York, Roth Horowitz Gallery, New York, NY Close Up sur David Wojnarowicz, Forum des Halles Espace Rencontres, Paris, France 2001 Featured Works VI: David Wojnarowicz: The Elements, Fire and Water, Earth and Wind, Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, IL 1999 Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz, New Museum, New York, NY David Wojnarowicz: The Boys Go Off