Temperature Scales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fahrenheit 1 Fahrenheit

Fahrenheit 1 Fahrenheit Fahrenheit is the temperature scale proposed in 1724 by, and named after, the physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736). Today, the temperature scale has been replaced by the Celsius scale in most countries.[1] It is still in use in few nations, such as United States and Belize.[2] Thermometer with Fahrenheit units on the outer scale and Celsius units on the inner scale Definition and conversions Fahrenheit temperature conversion formulae from Fahrenheit to Fahrenheit Celsius [°C] = ([°F] − 32) × 5 [°F] = [°C] × 9 + 32 ⁄9 ⁄5 Kelvin [K] = ([°F] + 459.67) × 5 [°F] = [K] × 9 − 459.67 ⁄9 ⁄5 Rankine [°R] = [°F] + 459.67 [°F] = [°R] − 459.67 For temperature intervals rather than specific temperatures, 1 °F = 1 °R = 5 °C = 5 K ⁄9 ⁄9 Comparisons among various temperature scales On the Fahrenheit scale, the freezing point of water is 32 degrees Fahrenheit (°F) and the boiling point 212 °F (at standard atmospheric pressure), placing the boiling and freezing points of water exactly 180 degrees apart.[3] A degree on the Fahrenheit scale is 1⁄ of the interval between the freezing point and the boiling point. On the Celsius 180 scale, the freezing and boiling points of water are 100 degrees apart. A temperature interval of 1 degree Fahrenheit is equal to an interval of 5⁄ degrees Celsius. The Fahrenheit and Celsius scales converge at −40 degrees (i.e. −40 °F 9 and −40 °C represent the same temperature).[3] Absolute zero is −459.67 °F.[4] The Rankine temperature scale was created to use degree intervals the same size as those of the Fahrenheit scale, such that a temperature difference of one degree Rankine (1 °R) is equal to a difference of 1 °F, except that absolute zero is 0 °R – the same way that the Kelvin temperature scale matches the Celsius scale, except that absolute zero is 0 K. -

Water Heater Formulas and Terminology

More resources http://waterheatertimer.org/9-ways-to-save-with-water-heater.html http://waterheatertimer.org/Figure-Volts-Amps-Watts-for-water-heater.html http://waterheatertimer.org/pdf/Fundamentals-of-water-heating.pdf FORMULAS & FACTS BTU (British Thermal Unit) is the heat required to raise 1 pound of water 1°F 1 BTU = 252 cal = 0.252 kcal 1 cal = 4.187 Joules BTU X 1.055 = Kilo Joules BTU divided by 3,413 = Kilowatt (1 KW) FAHRENHEIT CENTIGRADE 32 0 41 5 To convert from Fahrenheit to Celsius: 60.8 16 (°F – 32) x 5/9 or .556 = °C. 120.2 49 140 60 180 82 212 100 One gallon of 120°F (49°C) water BTU output (Electric) = weighs approximately 8.25 pounds. BTU Input (Not exactly true due Pounds x .45359 = Kilogram to minimal flange heat loss.) Gallons x 3.7854 = Liters Capacity of a % of hot water = cylindrical tank (Mixed Water Temp. – Cold Water – 1⁄ 2 diameter (in inches) Temp.) divided by (Hot Water Temp. x 3.146 x length. (in inches) – Cold Water Temp.) Divide by 231 for gallons. % thermal efficiency = Doubling the diameter (GPH recovery X 8.25 X temp. rise X of a pipe will increase its flow 1.0) divided by BTU/H Input capacity (approximately) 5.3 times. BTU output (Gas) = GPH recovery x 8.25 x temp. rise x 1.0 FORMULAS & FACTS TEMP °F RISE STEEL COPPER Linear expansion of pipe 50° 0.38˝ 0.57˝ – in inches per 100 Ft. 100° .076˝ 1.14˝ 125° .092˝ 1.40˝ 150° 1.15˝ 1.75˝ Grain – 1 grain per gallon = 17.1 Parts Per million (measurement of water hardness) TC-092 FORMULAS & FACTS GPH (Gas) = One gallon of Propane gas contains (BTU/H Input X % Eff.) divided by about 91,250 BTU of heat. -

How Does the Thermometer Work?

How Does the Thermometer Work? How Does the Thermometer Work? A thermometer is a device that measures the temperature of things. The name is made up of two smaller words: "Thermo" means heat and "meter" means to measure. You can use a thermometer to tell the temperature outside or inside your house, inside your oven, even the temperature of your body if you're sick. One of the earliest inventors of a thermometer was probably Galileo. We know him more for his studies about the solar system and his "revolutionary" theory (back then) that the earth and planets rotated around the sun. Galileo is said to have used a device called a "thermoscope" around 1600 - that's 400 years ago!! The thermometers we use today are different than the ones Galileo may have used. There is usually a bulb at the base of the thermometer with a long glass tube stretching out the top. Early thermometers used water, but because water freezes there was no way to measure temperatures less than the freezing point of water. So, alcohol, which freezes at temperature below the point where water freezes, was used. The red colored or silver line in the middle of the thermometer moves up and down depending on the temperature. The thermometer measures temperatures in Fahrenheit, Celsius and another scale called Kelvin. Fahrenheit is used mostly in the United States, and most of the rest of the world uses Celsius. Kelvin is used by scientists. Fahrenheit is named after the German physicist Gabriel D. Fahrenheit who developed his scale in 1724. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2 February 15, 2006 . DRAFT Cambridge-MIT Institute Multidisciplinary Design Project This Dictionary/Glossary of Engineering terms has been compiled to compliment the work developed as part of the Multi-disciplinary Design Project (MDP), which is a programme to develop teaching material and kits to aid the running of mechtronics projects in Universities and Schools. The project is being carried out with support from the Cambridge-MIT Institute undergraduate teaching programe. For more information about the project please visit the MDP website at http://www-mdp.eng.cam.ac.uk or contact Dr. Peter Long Prof. Alex Slocum Cambridge University Engineering Department Massachusetts Institute of Technology Trumpington Street, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Cambridge. Cambridge MA 02139-4307 CB2 1PZ. USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel: +44 (0) 1223 332779 tel: +1 617 253 0012 For information about the CMI initiative please see Cambridge-MIT Institute website :- http://www.cambridge-mit.org CMI CMI, University of Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology 10 Miller’s Yard, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Mill Lane, Cambridge MA 02139-4307 Cambridge. CB2 1RQ. USA tel: +44 (0) 1223 327207 tel. +1 617 253 7732 fax: +44 (0) 1223 765891 fax. +1 617 258 8539 . DRAFT 2 CMI-MDP Programme 1 Introduction This dictionary/glossary has not been developed as a definative work but as a useful reference book for engi- neering students to search when looking for the meaning of a word/phrase. It has been compiled from a number of existing glossaries together with a number of local additions. -

MODULE 11: GLOSSARY and CONVERSIONS Cell Engines

Hydrogen Fuel MODULE 11: GLOSSARY AND CONVERSIONS Cell Engines CONTENTS 11.1 GLOSSARY.......................................................................................................... 11-1 11.2 MEASUREMENT SYSTEMS .................................................................................. 11-31 11.3 CONVERSION TABLE .......................................................................................... 11-33 Hydrogen Fuel Cell Engines and Related Technologies: Rev 0, December 2001 Hydrogen Fuel MODULE 11: GLOSSARY AND CONVERSIONS Cell Engines OBJECTIVES This module is for reference only. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Engines and Related Technologies: Rev 0, December 2001 PAGE 11-1 Hydrogen Fuel Cell Engines MODULE 11: GLOSSARY AND CONVERSIONS 11.1 Glossary This glossary covers words, phrases, and acronyms that are used with fuel cell engines and hydrogen fueled vehicles. Some words may have different meanings when used in other contexts. There are variations in the use of periods and capitalization for abbrevia- tions, acronyms and standard measures. The terms in this glossary are pre- sented without periods. ABNORMAL COMBUSTION – Combustion in which knock, pre-ignition, run- on or surface ignition occurs; combustion that does not proceed in the nor- mal way (where the flame front is initiated by the spark and proceeds throughout the combustion chamber smoothly and without detonation). ABSOLUTE PRESSURE – Pressure shown on the pressure gauge plus at- mospheric pressure (psia). At sea level atmospheric pressure is 14.7 psia. Use absolute pressure in compressor calculations and when using the ideal gas law. See also psi and psig. ABSOLUTE TEMPERATURE – Temperature scale with absolute zero as the zero of the scale. In standard, the absolute temperature is the temperature in ºF plus 460, or in metric it is the temperature in ºC plus 273. Absolute zero is referred to as Rankine or r, and in metric as Kelvin or K. -

The Kelvin and Temperature Measurements

Volume 106, Number 1, January–February 2001 Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology [J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 106, 105–149 (2001)] The Kelvin and Temperature Measurements Volume 106 Number 1 January–February 2001 B. W. Mangum, G. T. Furukawa, The International Temperature Scale of are available to the thermometry commu- K. G. Kreider, C. W. Meyer, D. C. 1990 (ITS-90) is defined from 0.65 K nity are described. Part II of the paper Ripple, G. F. Strouse, W. L. Tew, upwards to the highest temperature measur- describes the realization of temperature able by spectral radiation thermometry, above 1234.93 K for which the ITS-90 is M. R. Moldover, B. Carol Johnson, the radiation thermometry being based on defined in terms of the calibration of spec- H. W. Yoon, C. E. Gibson, and the Planck radiation law. When it was troradiometers using reference blackbody R. D. Saunders developed, the ITS-90 represented thermo- sources that are at the temperature of the dynamic temperatures as closely as pos- equilibrium liquid-solid phase transition National Institute of Standards and sible. Part I of this paper describes the real- of pure silver, gold, or copper. The realiza- Technology, ization of contact thermometry up to tion of temperature from absolute spec- 1234.93 K, the temperature range in which tral or total radiometry over the tempera- Gaithersburg, MD 20899-0001 the ITS-90 is defined in terms of calibra- ture range from about 60 K to 3000 K is [email protected] tion of thermometers at 15 fixed points and also described. -

Temperature Scales (Celsius Vs Fahrenheit)

TEMPERATURE SCALES (CELSIUS VS FAHRENHEIT) The Celsius (also known as centigrade) temperature scale is the overwhelmingly popular scale around the world. Americans are really the only folks stubborn enough to hang on to our old habits. Anders Celsius, (1701 – 1744) born in Uppsala Sweden, was one of a large number of scientists (all related) originating from Ovanåker in the province of Hälsingland. The family name is a latinised version of the name of the vicarage (Högen). His grandfathers were both professors in Uppsala: Magnus Celsius the mathematician and Anders Spole the astronomer. His father, Nils Celsius, was also professor in astronomy. Celsius, who was said to have been very talented in mathematics from an early age, was appointed professor of astronomy in 1730. For his metereological observations he constructed his world famous Celsius thermometer, with 0 for the boiling point of water and 100 for the freezing point. After his death in 1744 the scale was reversed to its present form. http://www.astro.uu.se/history/Celsius_eng.html What can be considered the first modern thermometer, the mercury thermometer with a standardized scale, was invented by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686-1736) in 1714. The Fahrenheit scale divided the freezing and boiling points of water into 180 degrees. 32°F was the freezing p0int of water and 212°F was the boiling point of water. 0°F was based on the temperature of an equal mixture of water, ice, and salt. Daniel Fahrenheit based his temperature scale on the temperature of the human body. Originally, the human body temperature was 100° F on the Fahrenheit scale, but it has since been adjusted to 98.6°F. -

TEMPERATURE © 2019, 2008, 2004, 1990 by David A

TEMPERATURE © 2019, 2008, 2004, 1990 by David A. Katz. All rights reserved. A BRIEF HISTORY OF TEMPERATURE MEASUREMENT Ancient people were physically aware of hot and cold and probably related temperature by the size of the fire needed, and how close to sit, to keep warm. An Australian tribe, still primitive, uses dogs instead of blankets to keep warm, thus, they can relate temperature by the dog. (See Figure 1.) A moderately cool night may require two dogs to keep warm, thus it is a two-dog night. An icy night would be a six-dog night. Early people were, at first, fire tenders, maintaining fires originally Figure 1. Australian started by natural causes. Later, they learned how to make fire and aborginies use dogs became fire makers. Eventually, they became fire managers as they to keep warm. learned to work with fire to gain the heat needed to boil water, cook meat, fire pottery (500°F or 257°C), work with copper, tin, bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) and iron, and to make glass. (See Figure 2) Although they had no quantitative measuring devices to determine how hot a fire was, they developed recipes for building different types of fires and probably used a physical indicator, such as some mineral or metal melting, to indicate the correct Figure 2. Early people temperature for a particular process. used fire to cook food and later to work with The ancient Greeks knew that air expanded when heated and metals. applied the principle mechanically, but they developed no means of measuring temperature or amount of heat needed and devised no measuring instruments. -

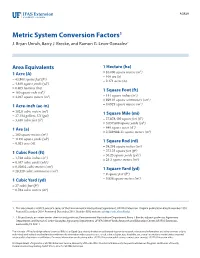

Metric System Conversion Factors1 J

AGR39 Metric System Conversion Factors1 J. Bryan Unruh, Barry J. Brecke, and Ramon G. Leon-Gonzalez2 Area Equivalents 1 Hectare (ha) 2 1 Acre (A) = 10,000 square meters (m ) 2 = 100 are (a) = 43,560 square feet (ft ) = 2.471 acres (A) = 4,840 square yards (yd2) = 0.405 hectares (ha) 1 Square Foot (ft) = 160 square rods (rd2) 2 = 4,047 square meters (m2) = 144 square inches (in ) = 929.03 square centimeters (cm2) 2 1 Acre-inch (ac-in) = 0.0929 square meters (m ) 3 = 102.8 cubic meters (m ) 1 Square Mile (mi) = 27,154 gallons, US (gal) 2 = 3,630 cubic feet (ft3) = 27,878,400 square feet (ft ) = 3,097,600 square yards (yd2) 2 1 Are (a) = 640 square acres (A ) = 2,589,988.11 square meters (m2) = 100 square meters (m2) 2 = 119.6 square yards (yd ) 1 Square Rod (rd) = 0.025 acre (A) = 39,204 square inches (in2) = 272.25 square feet (ft2) 1 Cubic Foot (ft) 2 3 = 30.25 square yards (yds ) = 1,728 cubic inches (in ) = 25.3 square meters (m2) = 0.037 cubic yards (yds3) 3 = 0.02832 cubic meters (cm ) 1 Square Yard (yd) = 28,320 cubic centimeters (cm3) = 9 square feet (ft2) 2 1 Cubic Yard (yd) = 0.836 square meters (m ) = 27 cubic feet (ft3) = 0.764 cubic meters (m3) 1. This document is AGR39, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date November 1993. Revised December 2014. Reviewed December 2017. Visit the EDIS website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. -

Enghandbook.Pdf

785.392.3017 FAX 785.392.2845 Box 232, Exit 49 G.L. Huyett Expy Minneapolis, KS 67467 ENGINEERING HANDBOOK TECHNICAL INFORMATION STEELMAKING Basic descriptions of making carbon, alloy, stainless, and tool steel p. 4. METALS & ALLOYS Carbon grades, types, and numbering systems; glossary p. 13. Identification factors and composition standards p. 27. CHEMICAL CONTENT This document and the information contained herein is not Quenching, hardening, and other thermal modifications p. 30. HEAT TREATMENT a design standard, design guide or otherwise, but is here TESTING THE HARDNESS OF METALS Types and comparisons; glossary p. 34. solely for the convenience of our customers. For more Comparisons of ductility, stresses; glossary p.41. design assistance MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF METAL contact our plant or consult the Machinery G.L. Huyett’s distinct capabilities; glossary p. 53. Handbook, published MANUFACTURING PROCESSES by Industrial Press Inc., New York. COATING, PLATING & THE COLORING OF METALS Finishes p. 81. CONVERSION CHARTS Imperial and metric p. 84. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Steelmaking 4 Metals and Alloys 13 Designations for Chemical Content 27 Designations for Heat Treatment 30 Testing the Hardness of Metals 34 Mechanical Properties of Metal 41 Manufacturing Processes 53 Manufacturing Glossary 57 Conversion Coating, Plating, and the Coloring of Metals 81 Conversion Charts 84 Links and Related Sites 89 Index 90 Box 232 • Exit 49 G.L. Huyett Expressway • Minneapolis, Kansas 67467 785-392-3017 • Fax 785-392-2845 • [email protected] • www.huyett.com INTRODUCTION & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document was created based on research and experience of Huyett staff. Invaluable technical information, including statistical data contained in the tables, is from the 26th Edition Machinery Handbook, copyrighted and published in 2000 by Industrial Press, Inc. -

Thermodynamic Temperature

Thermodynamic temperature Thermodynamic temperature is the absolute measure 1 Overview of temperature and is one of the principal parameters of thermodynamics. Temperature is a measure of the random submicroscopic Thermodynamic temperature is defined by the third law motions and vibrations of the particle constituents of of thermodynamics in which the theoretically lowest tem- matter. These motions comprise the internal energy of perature is the null or zero point. At this point, absolute a substance. More specifically, the thermodynamic tem- zero, the particle constituents of matter have minimal perature of any bulk quantity of matter is the measure motion and can become no colder.[1][2] In the quantum- of the average kinetic energy per classical (i.e., non- mechanical description, matter at absolute zero is in its quantum) degree of freedom of its constituent particles. ground state, which is its state of lowest energy. Thermo- “Translational motions” are almost always in the classical dynamic temperature is often also called absolute tem- regime. Translational motions are ordinary, whole-body perature, for two reasons: one, proposed by Kelvin, that movements in three-dimensional space in which particles it does not depend on the properties of a particular mate- move about and exchange energy in collisions. Figure 1 rial; two that it refers to an absolute zero according to the below shows translational motion in gases; Figure 4 be- properties of the ideal gas. low shows translational motion in solids. Thermodynamic temperature’s null point, absolute zero, is the temperature The International System of Units specifies a particular at which the particle constituents of matter are as close as scale for thermodynamic temperature.