Pn-Ffer:- Cf'to L\O~1S""

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wedding Menu

COCKTAIL HOUR Butlered Hors D’Oeuvres All Included Broccoli Cheese Bites Beef Brochette Baby Lamb Chops Crab Rangoon Spanakopita Chicken Tacos Coconut Shrimp Stuffed Jalapeno Wrapped in Bacon Duck Spring Rolls Chicken Skewers Pot Stickers Mushroom Risotto in Phyllo Chicken Cordon Bleu Chicken Parmesan Spring Rolls Deviled Eggs Vegetable Spring Roll Chicken Wrapped in Bacon Lobster Egg Roll Mushroom Stuffed with Crabmeat Ratatouille Cups Fried Ravioli Asparagus Provolone Cheese Wrap Shrimp Wrapped in Bacon Lemon Spice Chicken Cheesesteak Egg Roll Macaroni & Cheese Bites Scallops Wrapped in Bacon Mini Beef Wellingtons Honey Goat Cheese Triangles Raspberry & Brie Tart Tomato Basil Arancini Mushroom Vol-au-vent - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Toscano Table All Included Caprese Salad Toasted Croustades Hummus Spread Shrimp Cocktail Assorted Marinated Mushrooms Tuna Salad Chicken Salad Fresh Seafood Salad Soppressata Hot Roasted Italian Peppers Roasted Pepper Caponata Mediterranean Olives Grilled Vegetables Baba Ghanoush Sliced Prosciutto Fresh Fruit Bruschetta Pesto Pasta Salad House- Made Pickles Artisan Meats & Cheeses Pita Bread Prosciutto & Provolone Peppers 1 COCKTAIL HOUR Attended Stations Pizza Station – Included Chef’s Choice Assorted Gourmet Flatbread Pizzas - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Pasta Station – Choice of (2) Gemelli Raphael: Tossed with spinach, roma tomatoes and crab meat in -

Lox Stock & Bagel

SALADS FOR THE CHILDREN LOX STOCK & BAGEL 2439 Battleground Avenue •336-288-2894 Tossed Salad Small 4.75 Smaller portions, served on White Large 5.75 or Whole Wheat with a pickle spear. 3.95 www.loxstockandbagel.net Chef Salad Small 5.75 Large 6.95 Choose Chips, Goldfish or Carrot Sticks. Greek Salad Small 4.95 Skydog Corned Beef • Turkey Breast • Ham • Swiss • American • Provolone Greek olives contain pits Large 6.75 Any Meat & Cheese 8.50 10.50 Lettuce • Tomato • Onion • Special Dressing • On Sub Roll Hamburger or Cheeseburger Hot Dog Italian Sub Genoa Salami • Cappicola • Provolone • Imported Ham • Sliced Cherry Peppers Add Grilled Chicken or PBJ 7.75 9.95 Lettuce • Tomato • Onion • Special Dressing • On Sub Roll Garden Burger to any Salad 2.50 Toasted Cheese Add Hard Boiled Egg .75 Mini Pizza Cheese Sub Provolone • Swiss • American • Hot or Cold • Lettuce • Tomato • Onion 7.25 8.75 Special Dressing • On Sub Roll BEVERAGES Hackensack Imported Ham • Turkey Breast • Swiss Cheese • Cole Slaw • Russian Dressing Canned Sodas (Coke Products) 1.25 ON LETTUCE BEDS 7.75 On Rye or Pumpernickel Dr. Brown’s Soda 1.50 1H71CKHIVF8 Tuna or Chicken Salad 4.50 Bottled Sodas & Juices 1.75 Egg Salad 3.95 Kais R.B. 5 oz. Roast Beef • Russian Dressing • Cole Slaw • On Kaiser Roll Tea 16oz.- .95 32oz -1.50 Cottage Cheese 1.95 7.95 Pickled Herring (Wine or Cream) 6.50 Coffee 1.25 Milk .95 Fresh Cut Fruits (Seasonal) 3.75 Super Turk Turkey Breast • Swiss Cheese • Lettuce • Tomato • Russian Dressing Bottled Water 1.50 7.75 On Kaiser Roll Orangina 1.95 Italian Sailor Pastrami • Pepperoni • Swiss Cheese • Deli Mustard • Served Hot on Rye SIDE ORDERS 7.75 Potato Knish 3.95 Sailor Pastrami • Knockwurst • Swiss Cheese • Deli Mustard • Served Hot on Rye Baked Beans 1.50 7.95 New York Style Potato Salad 1.50 BEERS Hot German Potato Salad 1.50 Domestic Bottle 2.95 Knickerbocker Beef Knockwurst • Sauerkraut • Swiss Cheese • Deli Mustard • On Rye or Macaroni Salad 1.50 Premium Bottle 3.95 7.50 Pumpernickel Pasta Salad 1.50 On Draft 16oz. -

Catering EST

Catering EST. 1994 SPECIALTY SAMPLER FINGER TRAY – SIMPLY DELICIOUS! A delicious assortment of some of our most Triangles of turkey, ham and chicken salad popular sandwiches, garnished with olive, pickles sandwiches on white and whole wheat breads. and peppers – a tray you will be proud to display. Sm. $31.99 Med. $41.99 Lg. $51.99 The 1 1 * can be cut in /2’s or /4’s W Sm. $46.49 Med. $58.49 Lg. $69.99 RE (srv. 6-8) (srv. 10-12) (srv. 12-15) BROWNIES & COOKIES SC Dark, rich brownies with chocolate chip and K WRAPS TRAY oatmeal cookies. COR An artistic display of colorful tortilla wrapped Serves 20-25 .............................................. $37.99 sandwiches arranged with flair. Sm. $46.49 Med. $58.49 Lg. $69.99 (srv. 6-8) (srv. 10-12) (srv. 12-15) COOKIE TRAY Tray with chocolate chip and oatmeal raisin cookies. DELI NEW YORK DELI TRAY Over stuffed roast beef, corned beef and turkey Sm. $23.99 Lg. $35.99 sandwiches on rye, white and marble breads with sides of mayo and mustard. Sandwich Sm. $46.49 Med. $58.49 Lg. $69.99 TRAYED SALADS (srv. 6-8) (srv. 10-12) (srv. 12-15) Greek – $39.99 Tossed – $34.99 Construction Serves 10-15 PANINI TRAY Specialists A mouth-watering tray of our cubans, sicilians and paisanos grilled to perfection. Sm. $43.99 Med. $54.99 Lg. $65.99 (srv. 6-10) (srv. 10-12) (srv. 12-16) SIDE SALADS Potato Salad – $4.99 LB Pasta Salad – $5.99 LB OURS *Don’t see what you would like? H Just ask! MON - SAT 10 AM - 4 PM We will do our best to please you! Box Lunches Easy Catering “The Landings Plaza” 4982 S. -

112 Moulton Street East Decatur, AL 35601 Phone

112 Moulton Street East Decatur, AL 35601 Phone: 256-355-8318 www.brickdeli.com *ALL SANDWICHES COME WITH A Our Specialties PICKLE SPEAR AND CHOICE OF SIDE & CAN BE MADE “AS A SALAD” !! CASA DEL GRANDE DOWNTOWN HOAGIE CHICAGO FIRE Ham, turkey, roast beef, provolone, Ham, turkey, salami, smoked cheddar, Corned beef on a long white hoagie roll smoked cheddar and Swiss cheeses, provolone, onions, pepperoncini, garlic with mayo, hot mustard, hot pepper jack curry sauce, and a dash of soy sauce. All powder, crushed red pepper, mayo, and Swiss cheeses, onions, jalapenos, the condiments you can imagine: onions, Italian dressing, lettuce and tomatoes all mushrooms and tomatoes. bell peppers, mushrooms, black and on a long white hoagie roll. $ 10.00 green olives, lettuce and tomatoes on a $ 11.00 long white hoagie roll. $ 11.00 FATHER GUIDO 5 FINGER BANJO PICKER REUBEN A steamy pita, filled with Polish sausage, Polish sausage, Swiss cheese, sauerkraut, Toasty rye bread, steamy corned beef, pepperoncini, onions, provolone cheese, onions, jalapenos, hot mustard, and Swiss cheese, sauerkraut, mayo, and deli Italian seasonings, Italian dressing, deli tomatoes all on toasty rye bread. mustard. mustard, lettuce and tomatoes. $ 10.50 $ 9.75 $ 10.50 TURKEY SURPRISE THOMPSON REUBEN MELTDOWN Smoked turkey, smoked cheddar, Smoked turkey, Swiss cheese, Sharp cheddar cheese melted over provolone, mushrooms, curry powder, sauerkraut, mayo and deli mustard on tomatoes, hot mustard, mushrooms, a dash of soy sauce, mayo, and toasty rye bread. onions, curry powder and jalapenos tomatoes on a fresh onion roll. $ 9.75 on toasty rye bread. $ 9.75 $ 8.50 ROB’S RYE & ROAST SMOKEY JOE CASEY’S PHILLY Jewish rye bread, lean roast beef, hot Smoked turkey, smoked cheddar and Long white hoagie roll, lean roast beef, mustard, onions, jalapenos, hot pepper Swiss cheese, bacon and thousand island mayo, Swiss cheese, onions, bell jack cheese, mushrooms, lettuce and dressing. -

Arby's® Menu Items and Ingredients

Arby’s® Menu Items and Ingredients LIMITED TIME OFFERS Half Pound French Dip & Swiss/Au Jus: Roast Beef, Au Jus, Buttermilk Chicken Cordon Bleu: Buttermilk Chicken Fillet, Cinnamon Apple Crisp Swiss Cheese (Processed Slice), Sub Roll. Pit-Smoked Ham, Mayonnaise, Swiss Cheese (Natural Slice), Star Cut Bun. Cinnamon Apple Crisp, Whipped Topping. Arby’s Sauce® Buttermilk Buffalo Chicken: Buttermilk Chicken Fillet, Coke Float Horsey Sauce® Coca Cola, Vanilla Shake Mix. Parmesan Peppercorn Ranch Sauce, Spicy Buffalo Sauce, Three Cheese: Roast Beef, Parmesan Peppercorn Ranch Shredded Iceberg Lettuce, Star Cut Bun. Sauce, Swiss Cheese (Processed Slice), Cheddar Cheese Chicken Tenders SIGNATURE (Sharp Slice), Cheddar Cheese (Shredded), Crispy Onions, Smokehouse Brisket: Smoked Brisket, Smoky Q Sauce, Star Cut Bun. Tangy Barbeque Sauce Buffalo Dipping Sauce Mayonnaise, Smoked Gouda Cheese, Crispy Onions, Star Fire-Roasted Philly: Roast Beef, Roasted Garlic Aioli, Swiss Cut Bun. Cheese (Processed Slice), Italian Seasoning Blend, Red & Honey Mustard Dipping Sauce Traditional Greek Gyro: Gyro Meat, Gyro Sauce, Gyro Yellow Peppers, Sub Roll. Ranch Dipping Sauce Seasoning, Tomatoes, Shredded Iceberg Lettuce, Red Onion, Flatbread. TURKEY SLIDERS Turkey Gyro: Roast Turkey, Gyro Sauce, Gyro Seasoning, Grand Turkey Club: Roast Turkey, Pepper Bacon, Swiss Pizza Slider: Genoa Salami, Pepperoni, Swiss Cheese Red Onion, Tomatoes, Shredded Iceberg Lettuce, Flatbread. Cheese (Processed Slice), Tomatoes, (Processed Slice), Robust Marinara, Split Top Bun. Roast Beef Gyro: Roast Beef, Gyro Sauce, Gyro Seasoning, Leaf Lettuce, Mayonnaise, Harvest Wheat Bun. Buffalo Chicken Slider: Prime-Cut Chicken Tenders, Red Onion, Tomatoes, Shredded Iceberg Lettuce, Flatbread. Roast Turkey Ranch & Bacon Sandwich: Roast Turkey, Parmesan Peppercorn Ranch Sauce, Spicy Buffalo Sauce, Loaded Italian: Pepperoni, Genoa Salami, Pit-Smoked Pepper Bacon, Red Onion, Tomatoes, Leaf Lettuce, Split Top Bun. -

2018-2019 Paper Tiger Menu

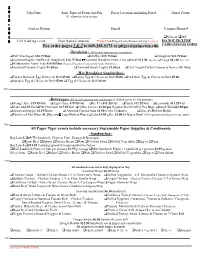

2 0____________________________ _______________ _________________________________ __________ 1 Day/Date Start Time of Event Am/Pm Exact Location including Rm # Guest Count We allow for delivery time 8 - ____________________________________ ____________________________________________ ______________ 2 Contact Person Email Campus Phone # 0 1________________________ ___________________ _____________________________ Visa or MC Cell # during event Dept Name/Company *Dept-Fund-Program-Site-Project-Activity*required DO NOT INCLUDE 9 Fax order pages 1 & 2 to 609-258-5173 or [email protected] CARD INFO ON FORM ~Breakfast~ All include appropriate condiments Full Size Bagels $16.75/Doz Muffins $15.75/Doz Doughnut $13.75/Doz Assorted Bagels, Muffins & Doughnuts $16.75/Doz Assorted Breakfast Pastry Tray Small $31.00 Apx 2dz Large $61.00 Apx 4dz Witherspoon Pastry Tray $19.95/Doz (Scones, Chocolate Croissants & Apple Turnovers) Assorted Dannon Yogurt $1.60/ea Assorted Greek Yogurt $2.50/ea 12oz Yogurt Parfait (Granola & Berries) $3.75/ea ~Hot Breakfast Sandwiches~ Turkey Bacon & Egg Whites on Roll $5.00 Bacon, Egg & Cheese on Roll $5.00 Pork Roll, Egg & Cheese on Roll $5.00 Spinach, Egg & Cheese on Roll $5.00 Egg & Cheese on Roll $4.00 Notes______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ~Beverages~ All include appropriate condiments (1 Gallon serves 16-8oz portions) Orange -

Zeus Grecian Island

Two locations serving you! Brighton • Lansing s h o w n w i t h to p p i ng & w hip ped cream 6 Authentic Taste • Real Value Carry Out Available great beginnings s a m p le WeAppetizer load this tantalizing Sampler platter with Platter mozzarella r pl cheese stix, cheese-stuffed jalapeño peppers and att er s golden chicken fingers. Great for sharing - 9.99 hown Saganaki Imported Kasseri cheese flamed tableside for a FChickenive tender Fingersbreaded chicken traditional Greek celebration of food. Opa! breast strips - 5.99 Served with fresh pita - 6.99 Mozzarella Cheese Stix (6) - 4.99 - 4.99 Zeus’ Chili Fry Supreme Fried Mushrooms A platter of fries, our chili sauce, shredded - 4.99 cheddar cheese, lettuce, tomatoes and onions. Fried Zucchini Sided with sour cream and salsa - 5.99 TheseWing meaty Dings lightly breaded wings are Stuffed Grape Leaves served plain or with your choice of Six stuffed grape leaves served buffalo or BBQ sauce chilled with fresh pita - 5.49 5 - 4.39 10 - 7.69 15 - 10.99 (6) - 4.99 AHummus middle Eastern delight! Ground chick peas with Stuffed Jalapeño Peppers tahini and select spices served with fresh pita - 5.49 FShrimpive succulent Cocktail chilled shrimp - 6.99 Get them deep-fried - 2.00 extra ATzatziki traditional blend of cucumber, garlic and yogurt served with fresh pita for dipping - 5.49 (Spanakopita) ASpinach Greek specialty! PieThin layers of filo pastry ThickOnion cut, Rings hand-battered and golden fried - 3.69 filled with garden fresh spinach, feta cheese and special seasonings. -

Kosher Cajun NY Deli and Grocery

Koshe r Cajun NY Deli and Grocery NEW YORK DELI 3519 Severn. Metairie, Louisiana 70002 & GROCERY (504)888-2010 • Fax (504) 888-2014 www.koshercajun.com H&4t~ ~ tJe/i til ~ ()~!" Appetizers Our Signature Deli Sandwiches Chopped Liver w/Crackers 5.95 J&N Special 9.95 Hummus w/Pita 5. 95 Hot Corned Beef & Pastrami on Rye Babaganoush w/Pita 5.95 w/Mustard, Horseradish & Coleslaw Kosher Shrimp w/Cocktail Sauce 6.95 Reuben 8.95 Stuffed Cabbage over White Rice 4.95 Hot Corned Beef on Toasted Rye Egg Roll with Duck Sauce 2.95 w/Russian Dressing and Sauerkraut Rachel 6.95 Whitefish Salad w/Crackers 4.95 Turkey Breast on Toasted Rye Relish Platter 2.95 w/Russian Dressing and Sauerkraut Turkey Breast & Chopped Liver 6.95 Soup & Salad on Rye wi Sliced Onion Matzoh Ball Soup Small 2.25 2.95 Roast Beef & Turkey 8.95 Soup of the Day Small 2.95 3.95 on Rye wlRussian and Coleslaw Fresh Garden Salad 3.95 Kosher Cajun House Salad 6.95 From The Grill Lettuce & tomato Topped with Turk ey Breast & Salami tl21b Grilled Hamburger & Fries 8.95 Grilled Chicken Salad 8.95 w/all the fi xins- lettuce, tomato & onion & Lettuce Tomato Topped with Grill ed Chi cken Breast Grilled Boneless Chicken Breast & Fries 8.95 Choice of: Lite Italian , Honey Mustard or Russian Dressing On Onion Roll wi lettuce &tomato Grilled Full Boneless Chicken Breast . 12.95 Side Orders Served wi salad & fri es Cole Slaw l.55 160z Rib Steak 24.95 Potato Salad l.55 Served wi salad & fries Sauerkraut 1.55 Lamb Chops 22.95 Served wi salad & fries Potato Chips/Bissli .69 Potato Latkes wi Applesauce 2.95 From The Fryer French Fries 1.95 Fried Fish Sandwich & Fries 5.95 on Onion Roll w/tartar sauce, lettuce & tomato 2.25 Sweet Potato Fries Fried Breaded Chicken Cutlet & Fries 8.95 Onion Rings 2.25 on Onion Roll wi lettuec & tomato N. -

OUR TOWN 39 Days in Lifeboat; Will Continue and Each Year Some- Were .Given! 172 Tuesday and 171 Distribute Musical Instruments, So

\ COMBINING The Summit Herald, Summit Kucord, Summit Press and Summit News-Guide OFFICIAL Official Newspaper of City ami Subscription $2.00 a Year County. Published Thursday A. M. by The Summit Publishing Co., 357 Telephone Summit G-1000 Springfield Avenue. Entered at tho Mailed in conformity with P. 0. D. Post Office, Summit, N. J., as 2nd Order No. 19087, rlERALD Class Matter. 54th Year. No. 34 FRED L. PALMER, Editor & Publisher THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 1943 J. EDWIN CARTER, Business Mgr. & Publisher 5 CENTS Red Cross Now REGISTER YOUR DOG H. S. Basketball Team SUMMIT MAN TELLS OF 39=DAY LIFEBOAT EXPERIENCES AT SEA Double Session Council Explains owners are glvm ten duys to purchase a license Meets Disapproval Curtailed Collection Knows It Must Raise mid official registration tu# Says Millkrn Boys- for pets. !)«(? regrlstrfttton started <w January 1 and Of Parents' Groups Of Ashes, Garbage Nearly $52,000 Here should him' been completed on Were Misrepresented the 30th. Summit residents, Andrew Genualdi, captain of Summit parents, led by Mrs. Garbage will be collected but The Summit Red Cross now however, did not se«ni to realize Bryant Marroun, president, of the once each week from the residen- knows it has the job of raisins Summit High School's basketball this fact, mid beginning Feb. 1, team and William Clarke, manager, Lincoln School Parent-Teacher As- tial district and ashes twice a wwk nearly $52,000 this year. (The exact the Summit Foilcc storied a sociation, have strongly opposed as at present, beginning Monday, amount is $51,900). have written a letter about a re- house to house canvass to port in the January 14 Herald of a the Board of Educatian's. -

Battle of Le Boulou Paulilles to Banyuls-Sur-Mer

P-OP-O Life LifeLife inin thethe Pyrénées-Orientales Pyrénées Orientales Out for the Day Battle of Le Boulou Walk The Region Paulilles to Banyuls-sur-Mer AMÉLIOREZ VOTRE ANGLAIS Autumn 2012 AND TEST YOUR FRENCH FREE / GRATUIT Nº 37 Your English Speaking Services Directory www.anglophone-direct.com Fond perdu 31/10/11 9:11 Page 1 Edito... Don’t batten down those hatches yet ‚ summer Register for our is most definitely not over here in the P-O and free weekly newsletter, we have many more long sunny days ahead. Lazy and stay up to date with WINDOWS, DOORS, SHUTTERS & CONSERVATORIES walks on deserted golden beaches, meanderings life in the Pyrénées-Orientales. www.anglophone -direct.com through endless hills, orchards and vines against a background of cloudless blue sky, that incredible Installing the very best since 1980 melange of every shade of green, red, brown and gold to delight Call or visit our showroom to talk the heart of artist and photographer, lift the spirits and warm the soul. with our English speaking experts. We also design Yes, autumn is absolutely my favourite time of the year with its dry warm days and and install beautiful cooler nights and a few drops of rain after such a dry summer will be very welcome! Unrivalled 30 year guarantee conservatories. We have dedicated a large part of this autumn P-O Life to remembrance, lest we ever forget the struggles and lost lives of the past which allow No obligation free quotation – Finance available subject to status us to sit on shady terraces in the present, tasting and toasting the toils of a land which has seen its fair share of blood, sweat and tears. -

P a R T Y T R A

Take The Great Taste of Mati’s Home! PARTY SUB* Three feet of fresh baked bread, piled high with turkey, honey ham and gourmet hard salami. FRESH SALADS Fresh lettuce, ripe tomatoes and onions, two cheeses (american and swiss) and Italian dressing on Albacore Tuna ............................................$9.99/lb. the side .................................................................................................. $44.95/ $15.00 each additional foot Chicken Salad ............................................$8.99/lb. DELI TRAY* Egg Salad ...................................................$7.75/lb. Pasta Salad ................................................$6.29/lb. Our Deli Trays look great and taste even better. Kosher-style corned beef cooked to juicy tenderness. Choice Fruit Salad ...............................................(seasonal) roast beef roasted to medium rare. Oven roasted turkey breast. Honest to goodness hickory smoked honey Potato Salad ...............................................$2.25/lb. cured ham and hard salami. All of this creatively arranged on a platter along with kosher dills, kalamata olives, pepperoncini, fresh tomato slices and garnished with fresh fruit. INCLUDES: Kosher Rye, condiments, Cole Slaw ...................................................$2.25/lb. napkins, plates and utensils. COMPLETE.......................................................................... $7.25 per person Seafood Salad ............................................$9.99/lb. DELUXE TRAY* CHOICE DELI MEATS A Deluxe Tray -

Sandwiches in America, Food & Wine You Just Inside the Red Door of the Blue House

Your pick-up order “The best reuben in America.” will be waiting for our mission — Twenty Best Sandwiches in America, Food & Wine you just inside the red door of the blue house. P u - piCk 3 Easy Steps to Ordering sandWIChes 1 Pick a sandwich 2 Pick a Size 3 Pick a Pickle Ask about our CHOOSE BY NOSHER Yiddish for “small eater”– these NEW cu up! SANDWICH NUMBER sandwiches still make for a pretty significant Crunchy, cucumbery rbside pick- or meal! Served on slightly smaller slices of bread with just a bit less filling inside. OLD BaguetTe Lunches Next DoOr! CHOOSE BY In a hurry? Check out our awesome array of dancing sandwiches Traditional, garlic-cured SANDWICH NAME FRESSER “big eater”– these bigger sandwiches made every morning on French baguettes. Just $6.99 each will satisfy almost any hearty appetite! or add a side salad, dessert & a drink for $10.99. Grab and go while they last. 422 edDie’s bIg deal A hearty plate of housemade corned beef hash served with buttered onion rye toast & Zingerman’s own spicy ketchup. #2 Zingerman’s Reuben “It’s killer!” —President Barack Obama $12.50 $15.50 Corned Beef 2 ZingermaN’s ReubEn 67 jon & amY’s douBLe dip 1 who’s greEnberg anywaY? In a NYC Slow Zingerman’s corned beef, Switzerland Swiss cheese, Zingerman’s corned beef & pastrami, Zingerman’s corned beef with chopped liver, Food corned beef Brinery sauerkraut & Russian dressing on grilled, Switzerland Swiss & Wisconsin muenster cheeses, leaf lettuce & our own Russian dressing on taste-test, a panel hand-sliced Jewish rye bread.