Artifacts and Representations of North Indian Art Music [*Ecompanion At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Androgynous Pariahs Gender Transformations and Politics of Culture in the North Indian Folk Theater Svāṅg

Karan Singh Government College for Women, Haryana, India Androgynous Pariahs Gender Transformations and Politics of Culture in the North Indian Folk Theater Svāṅg Theater in general and so-called “folk” theater forms in particular transpose derivative behavioral patterns onto performers by arranging them spatially within a circumscribed area. This power of theater to transform a person from his familiar, normative life to an altered “persona,” temporally and spatially, lingers on with the performer, individually as well as collectively, even when outside of the performance arena. At the same time, however, even while on the stage, a performer is never really an individual in the sense of having a dis- tinct consciousness, for he carries with him a considerable amount of baggage based on gender, caste, and other cultural determinants prominent within the Indian social sphere. While utilizing his dramatic capacity to transform his individual self into another being on stage, performance confers on the actor an opportunity to transcend social and gender boundaries. The present article seeks to understand the role played by ontological transformations and dis- guises as factors responsible for cultural condemnation of a well-known form of folk theater called svāṅg, due to the challenge it poses to the structural view of life undertaken by cultural purists as stable and fixed, particularly in the case of gender and social identities. At the same time it traces the genesis of opprobrium on folk theater as low-caste or low-class activity, resulting -

Und Audiovisuellen Archive As

International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives Internationale Vereinigung der Schall- und audiovisuellen Archive Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelles (I,_ '._ • e e_ • D iasa journal • Journal of the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives IASA • Organie de I' Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelle IASA • Zeitschchrift der Internationalen Vereinigung der Schall- und Audiovisuellen Archive IASA Editor: Chris Clark,The British Library National Sound Archive, 96 Euston Road, London NW I 2DB, UK. Fax 44 (0)20 7412 7413, e-mail [email protected] The IASA Journal is published twice a year and is sent to all members of IASA. Applications for membership of IASA should be sent to the Secretary General (see list of officers below). The annual dues are 25GBP for individual members and IOOGBP for institutional members. Back copies of the IASA Journal from 1971 are available on application. Subscriptions to the current year's issues of the IASA Journal are also available to non-members at a cost of 35GBP I 57Euros. Le IASA Journal est publie deux fois I'an etdistribue a tous les membres. Veuillez envoyer vos demandes d'adhesion au secretaire dont vous trouverez I'adresse ci-dessous. Les cotisations annuelles sont en ce moment de 25GBP pour les membres individuels et 100GBP pour les membres institutionels. Les numeros precedentes (a partir de 1971) du IASA Journal sont disponibles sur demande. Ceux qui ne sont pas membres de I'Association peuvent obtenir un abonnement du IASA Journal pour I'annee courante au coOt de 35GBP I 57 Euro. -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

Bachelor of Performing Arts (Vocal/Instrumental) I Semester

BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (VOCAL/INSTRUMENTAL) I SEMESTER Course - 101 (English (Spoken)) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 Course Objectives:- 1. To introduce students to the theory, fundamentals and tools of communication. 2. To develop vital communication skills for personal, social and professional interactions. 3. To effectively translate texts. 4. To understand and systematically present facts, idea and opinions. Course Content:- I. Introduction: Theory of Communication, Types and modes of Communication. II. Language of Communication: Verbal and Non-verbal (Spoken and Written) Personal, Social and Business, Barriers and Strategies Intra- personal, Inter-personal and Group communication. III. Speaking Skills: Monologue, Dialogue, Group Discussion, Effective Communication/ Mis-Communication, Interview, Public Speech. IV. Reading and Understanding: Close Reading, Comprehension, Summary, Paraphrasing, Analysis and Interpretation, Translation(from Indian language to English and Viva-versa), Literary/Knowledge Texts. V. Writing Skills: Documenting, Report Writing, Making notes, Letter writing Bibliographies: a. Fluency in English - Part II, Oxford University Press, 2006. b. Business English, Pearson, 2008. c. Language, Literature and Creativity, Orient Blackswan, 2013. d. Language through Literature (forthcoming) ed. Dr. Gauri Mishra, Dr Ranjana Kaul, Dr Brati Biswas Course - 102 (Hindi) Credits: 4 Marks: 80 Internal Assessment: 20 Total: 100 मध्यकालीन एवं आधुननक ह ंदी काव्य तथा व्याकरण Course Objective:- 1. पाठ्क्रम में रखी गई कनवता䴂 का ग न अध्ययन करना, उनपर चचाा करना, उनका नववेचन करना, कनवता䴂 का भावाथा स्पष्ट करना, कनवता की भाषा की नवशेषता䴂 तथा अथा को समझाना। 2. पाठ्क्रम में रखी गई खण्ड काव्य का ग न अध्ययन कराना,काव्यका भावाथा स्पष्ट करना, काव्य की भाषा की नवशेषता䴂 तथा अथा को समझाना। 3. -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary -

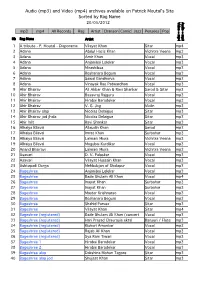

Archives Available on Patrick Moutal's Site Sorted by Rag Name Audio =Mp3 Audio 20/05/2012 =Mp4 Video

Audio (mp3) and Video (mp4) archives available on Patrick Moutal's Site Sorted by Rag Name Audio = mp3 20/05/2012 Video = mp4 mp3 mp4 All Records Rag Artist Chanson Comic Jazz Pensées Pop Nb Rag Name Artist 1 A tribute - P. Moutal - Diaporama Vilayat Khan Sitar mp4 2 Adana Abdul Haziz Khan Vichitra Veena mp3 3 Adana Amir Khan Vocal mp3 4 Adana Anjanibai Lolekar Vocal mp3 5 Adana Mirashibua Vocal mp3 6 Adana Roshanara Begum Vocal mp3 7 Adana Sawai Gandharva Vocal mp3 8 Adana Vinayak Rao Patwardhan Vocal mp3 9 Ahir Bhairav Ali Akbar Khan & Ravi Shankar Sarod & Sitar mp3 10 Ahir Bhairav Basavraj Rajguru Vocal mp3 11 Ahir Bhairav Hirabai Barodekar Vocal mp3 12 Ahir Bhairav V. G. Jog Violin mp3 13 Ahir Bhairav alap Nicolas Delaigue Sitar mp3 14 Ahir Bhairav jod jhala Nicolas Delaigue Sitar mp3 15 Ahir lalit Ravi Shankar Sitar mp3 16 Alhaiya Bilaval Allaudin Khan Sarod mp3 17 Alhaiya Bilaval Imrat Khan Surbahar mp3 18 Alhaiya Bilaval Lalmani Misra Vichitra Veena mp3 19 Alhaiya Bilaval Mogubai Kurdikar Vocal mp3 20 Anand Bhairavi Lalmani Misra Vichitra Veena mp3 21 Asavari D. V. Paluskar Vocal mp3 22 Asavari Vilayat Hussain Khan Vocal mp3 23 Ashtapadi Durga Mehbubjan of Sholapur Vocal mp3 24 Bageshree Anjanibai Lolekar Vocal mp3 25 Bageshree Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Vocal mp4 26 Bageshree Inayat Khan Surbahar mp3 27 Bageshree Inayat Khan Surbahar mp3 28 Bageshree Master Krishnarao Vocal mp3 29 Bageshree Roshanara Begum Vocal mp3 30 Bageshree Shahid Parvez Sitar mp3 31 Bageshree Vilayat Khan Sitar mp4 32 Bageshree (registered) Bade Ghulam Ali Khan -

The Gwalior Gharana of Khayal

THE GWALIOR GHARANA OF KHAYAL SusheeJa Misra The different gharanas in Khayal-singing have not only helped to preserve and perpetuate the older traditions through an unbroken lineage of Guru shishya-paratnpara, but also added much colour and infinite variety to Hindustani Music. In an article on "A spects of Karnatic Music", the late Sri G.N. Balasubramaniam (a famous performing artiste and scholar) wrote almost longingly:- "Unlike the Karnatak system, the Hindustani system is more elastic and flexible and comparatively free from inhibitions and restrictions. For instance, in the North there are several Gharanas--each one handling one and the same raga differently. In the South everywhere, every raga is ren dered alike". It is this scope for variety, choice of suitable style, and flights of fancy that have maintained the popul arity of the Khayal up till now. The precursors of the Khayal also used to be rendered in different styles. In ancient granthas, we come across mention of different types of "Geetis" such as "Shudhdha", "Bhinna", "Goudi", "Vesari", and "Saadhaarant", When the golden age of the Dhrupad began (during the Middle Ages), Dhrupad-gayan also had developed four "Baants" (meaning styles, or schools) namely, :-"Goudi" or "Gobarhari", "Daggur", "Khandar", and "Nowhar". When the majestic and ponderous Dhrupad had to give place to the .classico-romantic Khayal-form, the latter was developed and perfected into various styles which came to be known as "Gharanas", These "gharanas" gave an attractive variety to Khayal-singing,-each "gharana" developing its own distinctive features, although all of them were deeply rooted in a common underlying tradition or "Susampradaaya". -

Transcription and Analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love For

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Transcription and analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love for Western flute, sitar, tabla and tanpura Bethany Padgett Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Padgett, Bethany, "Transcription and analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love for Western flute, sitar, tabla and tanpura" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 511. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/511 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. TRANSCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF RAVI SHANKAR’S MORNING LOVE FOR WESTERN FLUTE, SITAR, TABLA AND TANPURA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Bethany Padgett B.M., Western Michigan University, 2007 M.M., Illinois State University, 2010 August 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am entirely indebted to many individuals who have encouraged my musical endeavors and research and made this project and my degree possible. I would first and foremost like to thank Dr. Katherine Kemler, professor of flute at Louisiana State University. She has been more than I could have ever hoped for in an advisor and mentor for the past three years. -

Breaking Boundaries: Bhangra As a Mechanism for Identity

Running head: BREAKING BOUNDARIES 1 Breaking Boundaries: Bhangra as a Mechanism for Identity Formation and Sociopolitical Refuge Among South Asian American Youths A Thesis Presented By Quisqueya G. Witbeck In the field of Global Studies & International Relations Northeastern University June 2018 BREAKING BOUNDARIES 2 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………...3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….4 Literature Review…………………………………………………………………………....4 Cultural Expression & Identity Formation………………………………………….6 Challenges to Plurality………………………………………………………………7 Expanding Scope & Audience………………………………………………………9 Implications of Cultural Fusion…………………………………………………….10 Summary...………………………………………………………………………….12 Methodology……………………………………....………………………………………...12 Topics……………………………………………………………………………….12 Subjects……………………………………………………………………………..14 Analysis……………………………………………………………………………..16 Data………………………………………………………………………………………......17 Kirapa ate Sakati Bhangra…………………………………………………………..18 The Comparison Group……………………………………………………………..18 The Individuals……………………………………………………………………...19 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………....27 Background………………………………………………………………………….27 Team Dynamics Structure & Authenticity ………………………………………….28 Originality: Crafting a Style………………………………………………………....31 Defining Desi: Negotiating Identity and Expectations in a Shared Medium………..32 Opinions & ideals.…………………………………………...……………...32 Credibility, expectations & exposure…………………...…………………..33 Refuge……………………………………………………………………………….36 Conclusions………………………………………………………………………………......39 -

Study Materials for Six Months Special Training Programme On

Six month Special Training Progaramme on Elementary Education for Primary School Teachers having B.Ed/B.Ed Special Edn/D.Ed (Special Edn.) (ODL Mode) Art Education, Work Education, Health & Physical Education West Bengal Board of Primary Education, Acharya Prafulla Chandra Bhaban D.K. - 7/1, Sector - 2 Bidhannagar, Kolkata - 700091 i West Bengal Board of Primary Education First edition : March, 2015 Neither this book nor any keys, hints, comments, notes, meanings, connotations, annotations, answers and solutions by way of questions and answers or otherwise should be printed, published or sold without the prior approval in writing of the President, West Bengal Board of Primary Education. Publish by Prof. (Dr) Manik Bhattacharyya, President West Bengal Board of Primary Education Acharyya Prafulla Chandra Bhavan, D. K. - 7/1, Sector - 2 Bidhannagar, Kolkata - 700091 ii Forewords It gives me immense pleasure in presenting the materials of Art, Health, Physical Education & Work Education for Six Month Special Training Programme in Elementary Education for the elementary school teachers in West Bengal, having B. Ed. / B. Ed. (Special Education)/ D. Ed. (Special Education). The materials being presented have been developed on the basis of the guidelines and syllabus of the NCTE. Care has been taken to make the presentation flawless and in perfect conformity with the guidelines of the NCTE. Lesson-units and activities given here are not exhaustive. Trainee-teachers are at liberty to plan & develop their own knowledge and skills through self learning under the guidance of the counselors and use of their previously acquired knowledge and skill of teaching. This humble effort will be prized, if the materials, developed here in this Course-book, are used by the teachers in the real classroom situations for the development of the four skills – Listening, Speaking, Reading and Writing of the elementary school children . -

Light on Pahari Culture Imtiaz Ahmad Hindus of the Himalayas by Gerald D Berreman, Bombay, Oxford University Press, 1963; Pp X +430, Price Rs 25.00

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY August 22, 1964 Book Review Light on Pahari Culture Imtiaz Ahmad Hindus of the Himalayas by Gerald D Berreman, Bombay, Oxford University Press, 1963; pp X +430, price Rs 25.00. THE Paharis living on the Himala- tern of landholding and structure of cial and economic levels. Thus, the yan foothills have always been re authority and political power. pure polluted or high-low caste dicho garded as Hindus, but there has hardly tomy is a striking feature of the Pahari been any serious attempt so far to The study is concerned primarily caste structure as distinguished from study their social structure and culture with an analysis of the village social the multiple division of the plains. Se and to compare them with the social system. The author shows that ties of condly, there are few ranked subcastes structure and culture of Hindus in kinship, caste and community consti among the indigeneous hill castes in and other culture areas. Berreman's tute three important levels of organiza around Bhatbair; the sub-divisions book is the first systematic anthropolo tion in the lives of the villagers. They (gotra, sib) are of equal rank and purity. gical study attempted on Pahari provide the structural basis for Pahari culture, and one of the very few studies culture and social interaction, and It seems that the author has over that have dealt with the Himalayan pe come into prominence in varying de stated the pure-polluted dichotomy in ople. It describes a central Pahari villa grees in different contexts. The ties Pahari caste structure in trying to dis ge in the broader contexts of Pahari of kinships are of most immediate sig tinguish it from the caste structure in and North Indian culture areas.