Introduction and Between the Testaments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CILICIA: the FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES in ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson

CILICIA: THE FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES IN ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson Summary This article explores the origin of the Christian church in Anatolia. While individual believers undoubtedly entered Anatolia during the 30s after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9–10), the book of Acts suggests that it was not until the following decade that the first church was organized. For it was at Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, that the first Christians appeared (Acts 11:20–26). Yet two obscure references in Acts point to the organization of churches in Cilicia at an earlier date. Among the addressees of the letter drafted by the Jerusalem council were the churches in Cilicia (Acts 15:23). Later Paul visited these same churches at the beginning of his second ministry journey (Acts 15:41). Paul’s relationship to these churches points to this apostle as their founder. Since his home was the Cilician city of Tarsus, to which he returned after his conversion (Gal. 1:21; Acts 9:30), Paul was apparently active in church planting during his so-called ‘silent years’. The core of these churches undoubtedly consisted of Diaspora Jews who, like Paul’s family, lived in the region. Jews from Cilicia were members of a Synagogue of the Freedmen in Jerusalem, to which Paul was associated during his time in Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) hellenized and urbanized Cilicia during his reign; the Romans around 39 BC added Cilicia Pedias to the province of Syria. Four cities along with Tarsus, located along or near the Pilgrim Road that transects Anatolia, constitute the most likely sites for the Cilician churches. -

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

THE EPONYMOUS OFFICIALS of GREEK CITIES: I Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 83 (1990) 249–288

ROBERT K. SHERK THE EPONYMOUS OFFICIALS OF GREEK CITIES: I aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 83 (1990) 249–288 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 249 The Eponymous Officials of Greek Cities: I (A) Introduction The eponymous official or magistrate after whom the year was named in Greek cities or as- sociations is well known to all epigraphists under various titles: archon, prytanis, stephanepho- ros, priest, etc. Some details about them have appeared in many articles and in scattered pas- sages of scholarly books. However, not since the publication of Clemens Gnaedinger, De Graecorum magistratibus eponymis quaestiones epigraphicae selectae (Diss. Strassburg 1892) has there been a treatment of the subject as a whole, although the growth of the material in this regard has been enormous.1 What is missing, however, is an attempt to bring the material up to date in a comprehensive survey covering the whole Greek world, at least as far as possible. The present article, of which this is only the first part, will present that material in a geographically organized manner: mainland Greece and the adjacent islands, then the Aegean islands, Asia Minor and Thrace, Syria, Egypt, Cyrene, Sicily, and southern Italy. All the epi- graphic remains of that area have been examined and catalogued. General observations and conclusions will be presented after the evidence as a whole has been given. I. Earliest Examples of Eponymity The earliest form of writing appeared in Sumer and Assyria sometime within the last half of the fourth millennium BC, and from there it spread westward. Thus, it is not at all surpris- ing that the Mesopotamian civilizations also made the earliest use of assigning names or events to years in dating historical records. -

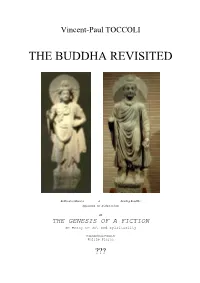

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

All About Indian History

Toprankers - Paramount SSC CGL Mock Test Get Test Series Put code - "EXAMPUNDIT" to avail discount Now Indian History - In Details INDIAN HISTORY PRE-HISTORIC as a part of a larger area called Pleistocene to the end of the PERIOD Jambu-dvipa (The continent of third Riss, glaciation. Jambu tree) The Palaeolithic culture had a The pre-historic period in the The stages in mans progress from duration of about 3,00,000 yrs. history of mankind can roughly Nomadic to settled life are The art of hunting and stalking be dated from 2,00,000 BC to 1. Primitive Food collecting wild animals individually and about 3500 – 2500 BC, when the stage or early and middle stone later in groups led to these first civilization began to take ages or Palaeolithic people making stone weapons shape. 2 . Advanced Food collecting and tools. The first modern human beings stage or late stone age or The principal tools are hand or Homo Sapiens set foot on the Mesolithic axes, cleavers and chopping Indian Subcontinent some- tools. The majority of tools where between 2,00,000 BC and 3. Transition to incipient food- found were made of quartzite. 40,000 BC and they soon spread production or early Neolithic They are found in all parts of through a large part of the sub- 4. settled village communities or India except the Central and continent including peninsular advanced neolithic/Chalco eastern mountain and the allu- India. lithic and vial plain of the ganges. They continuously flooded the 5. Urbanisation or Bronze age. People began to make ‘special- Indian subcontinent in waves of Paleolithic Age ized tools’ by flaking stones, migration from what is present which were pointed on one end. -

Alexander's Empire

4 Alexander’s Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Alexander the Alexander’s empire extended • Philip II •Alexander Great conquered Persia and Egypt across an area that today consists •Macedonia the Great and extended his empire to the of many nations and diverse • Darius III Indus River in northwest India. cultures. SETTING THE STAGE The Peloponnesian War severely weakened several Greek city-states. This caused a rapid decline in their military and economic power. In the nearby kingdom of Macedonia, King Philip II took note. Philip dreamed of taking control of Greece and then moving against Persia to seize its vast wealth. Philip also hoped to avenge the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. TAKING NOTES Philip Builds Macedonian Power Outlining Use an outline to organize main ideas The kingdom of Macedonia, located just north of Greece, about the growth of had rough terrain and a cold climate. The Macedonians were Alexander's empire. a hardy people who lived in mountain villages rather than city-states. Most Macedonian nobles thought of themselves Alexander's Empire as Greeks. The Greeks, however, looked down on the I. Philip Builds Macedonian Power Macedonians as uncivilized foreigners who had no great A. philosophers, sculptors, or writers. The Macedonians did have one very B. important resource—their shrewd and fearless kings. II. Alexander Conquers Persia Philip’s Army In 359 B.C., Philip II became king of Macedonia. Though only 23 years old, he quickly proved to be a brilliant general and a ruthless politician. Philip transformed the rugged peasants under his command into a well-trained professional army. -

Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 83 (1990) 194–214 © Dr

IAN WORTHINGTON ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND THE DATE OF THE MYTILENE DECREE aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 83 (1990) 194–214 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 194 ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND THE DATE OF THE MYTILENE DECREE The Mytilene decree1 is almost as controversial a document as the circumstances in which it was passed. Its contents, centring on the means by which returning exiles to Mytilene on the island of Lesbos could be reconciled with those resident there, point to a dating, presumably, of 324 BC, the year in which Alexander III of Macedon issued the famous Exiles Decree, applicable to the Greek cities.2 The text of the Exiles Decree is given at Diodorus 18.8.4, although it is quite likely that he did not quote it in its entirety since in this passage he states that all exiles except for those under a curse are to be restored to their native cities; elsewhere (17.109.1), he says those charged with sacrilege and murder are also excluded (cf. Curtius 10.2.4 and Justin 13.5.2), whilst Pseudo-Plutarch (Mor. 221a) indicates that the Thebans were also excluded.3 Although the Exiles Decree is inextricably linked to any assessment of the Mytilene decree, it is the latter which is the subject of this paper. 1 IG xii 2, 6, OGIS 2 = Tod, GHI ii no.201, SEG xiii 434. Especially significant is the new redaction (based on autopsy) and photograph (the first made available) of A.J. Heisserer, Alexander the Great and the Greeks: The Epigraphic Evidence (Norman: 1980) – hereafter Heisserer, Alexander – pp. -

Jeffrey Eli Pearson

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4dx9g1rj Author Pearson, Jeffrey Eli Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture By Jeffrey Eli Pearson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Erich Gruen, Chair Chris Hallett Andrew Stewart Benjamin Porter Spring 2011 Abstract Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture by Jeffrey Eli Pearson Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Erich Gruen, Chair The Nabataeans, best known today for the spectacular remains of their capital at Petra in southern Jordan, continue to defy easy characterization. Since they lack a surviving narrative history of their own, in approaching the Nabataeans one necessarily relies heavily upon the commentaries of outside observers, such as the Greeks, Romans, and Jews, as well as upon comparisons of Nabataean material culture with Classical and Near Eastern models. These approaches have elucidated much about this -

Nebuchadnezzar, Cyrus, Alexander & Herod

CODE 166 CODE 196 CODE 228 CODE 243 CODE 251 CODE 294 CODE 427 CODE 490 CODE 590 CODE 666 CODE 01010 CODE 1260 CODE1447 CODE 1900 CODE 1975 CODE 2300 CODE 6000 CODE 144000 49-year Pattern During Nebuchadnezzar, Cyrus, Alexander & Herod by FloydR. Cox (4/23/2021 Version) I revisited the 49-year pattern found during four empires: Babylon, Persia, Greece and http://code251.com/ Rome as found in the book of Daniel. Patterns tend to prove there is a Pattern-Maker. The Era of the Babylonian Empire Related Topics 1. In Daniel 2, Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon represented the “head of gold” of a great British Israelism Revisited image. Successive empires are represented by metals of lesser and lesser value than Ussher’s Jubilee gold: silver, brass and iron. The vision was in Nebuchadnezzar’s second year, in 604 in 1975 BC. Locating 251-year Patterns 2. In Daniel 4, Nebuchadnessar became like a beast for seven years (from 569 to 562 6000-Year Chart BC). 569 was 49 years before the second temple was founded in 520 BC, in the 2nd yr. (of Jubilees) of Darius II. Intelligent Design of the Ages Overview after Babylon Falls after 539 BC New Moons & Sabbaths are 3. In Daniel 7, in his first year, Belshazzar saw a vision of four beasts. A lion, bear, Foreshadows? leopard, and a beast with 10 horns and a little horn, which plucked up three of the first Timeline 6 BC to 70 AD horns. This leaves 8 horns (10-3=7 horns) (+1 horn).