Renaissance Influence on Post Byzantine Panel Painting in Crete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LATE RENAISSANCE and MANNERISM in SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY 591 17 CH17 P590-623.Qxp 4/12/09 15:24 Page 592

17_CH17_P590-623.qxp 12/10/09 09:24 Page 590 17_CH17_P590-623.qxp 12/10/09 09:25 Page 591 CHAPTER 17 CHAPTER The Late Renaissance and Mannerism in Sixteenth- Century Italy ROMTHEMOMENTTHATMARTINLUTHERPOSTEDHISCHALLENGE to the Roman Catholic Church in Wittenberg in 1517, the political and cultural landscape of Europe began to change. Europe s ostensible religious F unity was fractured as entire regions left the Catholic fold. The great powers of France, Spain, and Germany warred with each other on the Italian peninsula, even as the Turkish expansion into Europe threatened Habsburgs; three years later, Charles V was crowned Holy all. The spiritual challenge of the Reformation and the rise of Roman emperor in Bologna. His presence in Italy had important powerful courts affected Italian artists in this period by changing repercussions: In 1530, he overthrew the reestablished Republic the climate in which they worked and the nature of their patron- of Florence and restored the Medici to power. Cosimo I de age. No single style dominated the sixteenth century in Italy, Medici became duke of Florence in 1537 and grand duke of though all the artists working in what is conventionally called the Tuscany in 1569. Charles also promoted the rule of the Gonzaga Late Renaissance were profoundly affected by the achievements of Mantua and awarded a knighthood to Titian. He and his suc- of the High Renaissance. cessors became avid patrons of Titian, spreading the influence and The authority of the generation of the High Renaissance prestige of Italian Renaissance style throughout Europe. would both challenge and nourish later generations of artists. -

Biological Warfare Plan in the 17Th Century—The Siege of Candia, 1648–1669 Eleni Thalassinou, Costas Tsiamis, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou, Angelos Hatzakis

HISTORICAL REVIEW Biological Warfare Plan in the 17th Century—the Siege of Candia, 1648–1669 Eleni Thalassinou, Costas Tsiamis, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou, Angelos Hatzakis A little-known effort to conduct biological warfare oc- to have hurled corpses of plague victims into the besieged curred during the 17th century. The incident transpired city (9). During World War II, Japan conducted biological during the Venetian–Ottoman War, when the city of Can- weapons research at facilities in China. Prisoners of war dia (now Heraklion, Greece) was under siege by the Otto- were infected with several pathogens, including Y. pestis; mans (1648–1669). The data we describe, obtained from >10,000 died as a result of experimental infection or execu- the Archives of the Venetian State, are related to an op- tion after experimentation. At least 11 Chinese cities were eration organized by the Venetian Intelligence Services, which aimed at lifting the siege by infecting the Ottoman attacked with biological agents sprayed from aircraft or in- soldiers with plague by attacking them with a liquid made troduced into water supplies or food products. Y. pestis–in- from the spleens and buboes of plague victims. Although fected fleas were released from aircraft over Chinese cities the plan was perfectly organized, and the deadly mixture to initiate plague epidemics (10). We describe a plan—ul- was ready to use, the attack was ultimately never carried timately abandoned—to use plague as a biological weapon out. The conception and the detailed cynical planning of during the Venetian–Ottoman War in the 17th century. the attack on Candia illustrate a dangerous way of think- ing about the use of biological weapons and the absence Archival Sources of reservations when potential users, within their religious Our research has been based on material from the Ar- framework, cast their enemies as undeserving of humani- chives of the Venetian State (11). -

Crete 8 Days

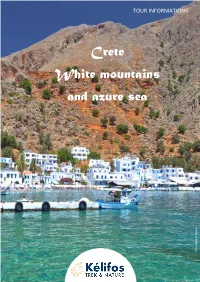

TOUR INFORMATIONS Crete White mountains and azure sea The village of Loutro village The SUMMARY Greece • Crete Self guided hike 8 days 7 nights Itinerant trip Nothing to carry 2 / 5 CYCLP0001 HIGHLIGHTS Chania: the most beautiful city in Crete The Samaria and Agia Irini gorges A good mix of walking, swimming, relaxation and visits of sites www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 1 / 13 MAP www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 2 / 13 P R O P O S E D ITINERARY Wild, untamed ... and yet so welcoming. Crete is an island of character, a rebellious island, sometimes, but one that opens its doors wide before you even knock. Crete is like its mountains, crisscrossed by spectacular gorges tumbling down into the sea of Libya, to the tiny seaside resorts where you will relax like in a dream. Crete is the quintessence of the alliance between sea and mountains, many of which exceed 2000 meters, especially in the mountain range of Lefka Ori, (means White mountains in Greek - a hint to the limestone that constitutes them) where our hike takes place. Our eight-day tour follows a part of the European E4 trail along the south-west coast of the island with magnificent forays into the gorges of Agia Irini and Samaria for the island's most famous hike. But a nature trip in Crete cannot be confined to a simple landscape discovery even gorgeous. It is in fact associate with exceptional cultural discoveries. The beautiful heritage of Chania borrows from the Venetian and Ottoman occupants who followed on the island. -

Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Byzantine 13th Century Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne c. 1260/1280 tempera on linden panel painted surface: 82.4 x 50.1 cm (32 7/16 x 19 3/4 in.) overall: 84 x 53.5 cm (33 1/16 x 21 1/16 in.) framed: 90.8 x 58.3 x 7.6 cm (35 3/4 x 22 15/16 x 3 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.1 ENTRY The painting shows the Madonna seated frontally on an elaborate, curved, two-tier, wooden throne of circular plan.[1] She is supporting the blessing Christ child on her left arm according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria.[2] Mary is wearing a red mantle over an azure dress. The child is dressed in a salmon-colored tunic and blue mantle; he holds a red scroll in his left hand, supporting it on his lap.[3] In the upper corners of the panel, at the height of the Virgin’s head, two medallions contain busts of two archangels [fig. 1] [fig. 2], with their garments surmounted by loroi and with scepters and spheres in their hands.[4] It was Bernard Berenson (1921) who recognized the common authorship of this work and Enthroned Madonna and Child and who concluded—though admitting he had no specialized knowledge of art of this cultural area—that they were probably works executed in Constantinople around 1200.[5] These conclusions retain their authority and continue to stir debate. -

Renaissance and Baroque Art

Brooks Education (901)544.6215 Explore. Engage. Experience. Renaissance and Baroque Art Memphis Brooks Museum of Art Permanent Collection Tours German, Saint Michael, ca. 1450-1480, limewood, polychromed and gilded , Memphis Brooks Museum of Art Purchase with funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Ben B. Carrick, Dr. and Mrs. Marcus W. Orr, Fr. And Mrs. William F. Outlan, Mr. and Mrs. Downing Pryor, Mr. and Mrs. Richard O. Wilson, Brooks League in memory of Margaret A. Tate 84.3 1 Brooks Education (901)544.6215 Explore. Engage. Experience. Dear Teachers, On this tour we will examine and explore the world of Renaissance and Baroque art. The French word renaissance is translated as “rebirth” and is described by many as one of the most significant intellectual movements of our history. Whereas the Baroque period is described by many as a time of intense drama, tension, exuberance, and grandeur in art. By comparing and contrasting the works made in this period students gain a greater sense of the history of European art and the great minds behind it. Many notable artists, musicians, scientists, and writers emerged from this period that are still relished and discussed today. Artists and great thinkers such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Michaelangelo Meisi da Caravaggio, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, Dante Alighieri, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Galileo Galilei were working in their respective fields creating beautiful and innovative works. Many of these permanent collection works were created in the traditional fashion of egg tempera and oil painting which the students will get an opportunity to try in our studio. -

A Venetian Rural Villa in the Island of Crete. Traditional and Digital Strategies for a Heritage at Risk Emma Maglio

A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk Emma Maglio To cite this version: Emma Maglio. A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk. Digital Heritage 2013, Oct 2013, Marseille, France. pp.83-86. halshs-00979215 HAL Id: halshs-00979215 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00979215 Submitted on 15 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk Emma Maglio Aix-Marseille University LA3M (UMR 7298-CNRS), LabexMed Aix-en-Provence, France [email protected] Abstract — The Trevisan villa, an example of rural built rather they were regarded with indifference or even hostility»3. heritage in Crete dating back to the Venetian period, was the These ones were abandoned or demolished and only recently, object of an architectural and archaeological survey in order to especially before Greece entered the EU, remains of Venetian study its typology and plan transformations. Considering its heritage were recognized in their value: but academic research ruined conditions and the difficulties in ensuring its protection, a and conservation practices slowly develop. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 10, Issue 02, 2021: 28-50 Article Received: 02-02-2021 Accepted: 22-02-2021 Available Online: 28-02-2021 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.18533/jah.v10i2.2053 The Enthroned Virgin and Child with Six Saints from Santo Stefano Castle, Apulia, Italy Dr. Patrice Foutakis1 ABSTRACT A seven-panel work entitled The Monopoli Altarpiece is displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts. It is considered to be a Cretan-Venetian creation from the early fifteenth century. This article discusses the accounts of what has been written on this topic, and endeavors to bring field-changing evidence about its stylistic and iconographic aspects, the date, the artists who created it, the place it originally came from, and the person who had the idea of mounting an altarpiece. To do so, a comparative study on Byzantine and early-Renaissance painting is carried out, along with more attention paid to the history of Santo Stefano castle. As a result, it appears that the artist of the central panel comes from the Mystras painting school between 1360 and 1380, the author of the other six panels is Lorenzo Veneziano around 1360, and the altarpiece was not a single commission, but the mounting of panels coming from separate artworks. The officer Frà Domenico d’Alemagna, commander of Santo Stefano castle, had the idea of mounting different paintings into a seven-panel altarpiece between 1390 and 1410. The aim is to shed more light on a piece of art which stands as a witness from the twilight of the Middle Ages and the dawn of Renaissance; as a messenger from the Catholic and Orthodox pictorial traditions and collaboration; finally as a fosterer of the triple Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance expression. -

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS ATHENS & CRETE, 12-21 MAY 2019 MEMORIAL SERVICES Sunday, 12 May 2019 10.45 – Commemorative service at the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral and wreath-laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Syntagma Square Location: Mitropoleos Street - Syntagama Square, Athens Wednesday, 15 May 2019 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town Friday, 17 May 2019 11.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Army Cadets Memorial Location: Kolymbari, Region of Chania 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno Saturday, 18 May 2019 10.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Greeks Location: Latzimas, Rethymno Region 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 13.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Greek-Australian Memorial | Presentation of RSL National awards to Cretan students Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str. (Efedron Axiomatikon Square), Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Inhabitants Location: 1, Kanari Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town 1 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Peace Memorial for Greeks and Allies Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno Sunday, 19 May 2019 10.00 – Official doxology Location: Presentation of Mary Metropolitan Church, Rethymno town 11.00 – Memorial service and wreath-laying at the Rethymno Gerndarmerie School Location: 29, N. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Icone Di Roma E Del Lazio 1

Icone di Roma e del Lazio 1 Icone di Roma Giorgio Leone Icone di Roma e del Lazio 1 Giorgio Leone Repertori dell’Arte del Lazio - 5/6 G. LEONE ICONE DI ROMA E DEL LAZIO ISBN 978-88-8265-731-4 Museo Soprintendenza per i Beni Storici, Artistici In copertina: Diffuso ed Etnoantropologici del Lazio Direzione Regionale per i Beni Culturali Madonna Advocata detta Madonna di San Sisto, tavola, cm 71.5 x 42.5, Chiesa del Rosario Lazio e Paesaggistici del Lazio a Monte Mario, Roma, particolare «L’ERMA» «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali Soprintendenza per i Beni Storici, Artistici ed Etnoantropologici del Lazio (Repertori, 5-6) Giorgio Leone Icone di Roma e del Lazio I TOMO «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER GIORGIO LEONE Icone di Roma e del Lazio Repertori dell'Arte del Lazio 5-6 Soprintendenza per i Beni Storici, «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER Artistici ed Etnoantropologici del Lazio Direzione editoriale Progetto scientifico e Roberto Marcucci direzione della collana Soprintendente ANNA IMPONENTE Redazione ROSSELLA VODRET Elena Montani Segreteria del Soprintendente Daniele Maras Laura Ceccarelli Dario Scianetti Direzione scientifica Rosalia Pagliarani Maurizio Pinto ANNA IMPONENTE con la collaborazione di Giorgia Corrado Rossella Corcione Coordinamento scientifico Archivio Fotografico Elaborazione immagini e impaginazione integrata GIORGIO LEONE Graziella Frezza, responsabile Soprintendenza Speciale per il Alessandra Montedoro Dario Scianetti Claudio Fabbri Maurizio Pinto Patrimonio Storico, Artistico ed Rossella Corcione -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university.