Aan Een Eenmaal Ingezette Speurtocht Naar 'De'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Reformed Orthodoxy

Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology Belt, H. van der Citation Belt, H. van der. (2006, October 4). Autopistia : the self-convincing authority of scripture in reformed theology. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4582 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). id7775687 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com 4 Reformed Orthodoxy The period of Reformed orthodoxy extends from the Reformation to the time that liberal theology became predominant in the European churches and universities. During the period the Lutheran, Reformed, and Anglican churches were the official churches in Protestant countries and religious polemics between Catholicism and Protestantism formed an integral part of the intense political strife that gave birth to modern Europe. Reformed orthodoxy is usually divided into three periods that represent three different stages; there is no watershed between these periods and it is difficult to “ ” determine exact dates. During the period of early orthodoxy the confessional and doctrinal codifications of Reformed theology took place. This period is characterized by polemics against the Counter-Reformation; it starts with the death of the second- generation Reformers (around 1565) and ends in the first decades of the seventeenth century.1 The international Reformed Synod of Dort (1618-1619) is a useful milestone, 2 “ because this synod codified Reformed soteriology. -

The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

FALL 2019 volume 6 issue 1 3 FROM RUTHERFORD HALL Dr. Barry J. York 4 FOUR CENTURIES AGO: AN HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE SYNOD OF DORT Dr. David G. Whitla 16 THE FIRST HEADING: DIVINE ELECTION AND REPROBATION Rev. Thomas G. Reid, Jr. 25 THE SECOND HEADING - CHRIST’S DEATH AND HUMAN REDEMPTION THROUGH IT: LIMITED ATONEMENT AT THE SYNOD OF DORDT AND SOME CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGICAL DEBATES Dr. Richard C. Gamble 33 THE THIRD HEADING: HUMAN CORRUPTION Rev. Keith A. Evans 39 THE FOURTH HEADING: “BOTH DELIGHTFUL AND POWERFUL” THE DOCTRINE OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE IN THE CANONS OF DORT Dr. C. J. Williams 47 THE FIFTH HEADING: THE PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS Dr. Barry J. York STUDY UNDER PASTORS The theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary Description Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is provided freely by RPTS faculty and other scholars to encourage the theological growth of the church in the historic, creedal, Reformed faith. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is published biannually online at the RPTS website in html and pdf. Readers are free to use the journal and circulate articles in written, visual, or digital form, but we respectfully request that the content be unaltered and the source be acknowledged by the following statement. “Used by permission. Article first appeared in Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal, the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (rpts.edu).” e d i t o r s General Editor: Senior Editor: Assistant Editor: Contributing Editors: Barry York Richard Gamble Jay Dharan Tom Reid [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] C. -

University of Groningen Developments in Structuring Of

University of Groningen Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology van den Belt, Hendrik Published in: Reformation und Rationalität IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Final author's version (accepted by publisher, after peer review) Publication date: 2015 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H. (2015). Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology: The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625) as Example. In H. J. Selderhuis, & E-J. Waschke (Eds.), Reformation und Rationalität (pp. 289-311). (Refo500 Academic Studies; Vol. 17). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 11-02-2018 1 Henk van den Belt 2 3 4 Developments in Structuring of Reformed Theology: 5 6 The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625) as Example. 7 8 9 10 11 12 Abstract 13 14 The Synopsis Purioris Theologiae (1625), an influential handbook of Reformed 15 dogmatics, began as a cycle of disputations. -

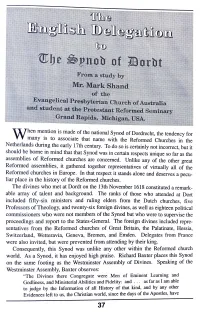

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and . -

The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip Van Limborch: a Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism

The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip van Limborch: A Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism By John Mark Hicks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Westminster Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy 1985 Faculty Advisor: Dr. Richard C. Gamble Second Faculty Reader: Mr. David W. Clowney Chairman, Field Committee: Dr. D. Claire Davis External Reader: Dr. Carl W. Bangs 2 Dissertation Abstract The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip van Limborch: A Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism By John Mark Hicks The dissertation addresses the problem of the theological relationship between the theology of Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609) and the theology of Philip van Limborch (1633-1712). Arminius is taken as a representative of original Arminianism and Limborch is viewed as a representative of developed Remonstrantism. The problem of the dissertation is the nature of the relationship between Arminianism and Remonstrantism. Some argue that the two systems are the fundamentally the same, others argue that Arminianism logically entails Remonstrantism and others argue that they ought to be radically distinguished. The thesis of the dissertation is that the presuppositions of Arminianism and Remonstrantism are radically different. The thesis is limited to the doctrine of grace. There is no discussion of predestination. Rather, the thesis is based upon four categories of grace: (1) its need; (2) its nature; (3) its ground; and (4) its appropriation. The method of the dissertation is a careful, separate analysis of the two theologians. -

THE SYNOD of DORT Many Reformed Churches Around the World Commemorate the Great Protestant Reformation Which Begun in Germany on October 31St 1517

THE SYNOD OF DORT Many Reformed Churches around the world commemorate the Great Protestant Reformation which begun in Germany on October 31st 1517. On that providential day, Martin Luther nailed his famed 95 Theses on the door of the castle church of Wittenberg. In no time, without Luther's knowledge, this paper was copied, and reproduced in great numbers with the recently invented printing machine. It was then distributed throughout Europe. This paper was to be used by our Sovereign Lord to ignite the Reformation which saw the release of the true Church of Christ from the yoke and bondage of Rome. Almost five hundred years have gone by since then. Today, there are countless technically Protestant churches (i.e. can trace back to the Reformation in terms of historical links) around the world. But there are few which still remember the rich heritage of the Reformers. In fact, a great number of churches which claim to be Protestant have, in fact, gone back to Rome by way of doctrine and practice, and some even make it their business to oppose the Reformers and their heirs. I am convinced that one of the chief reasons for this state of affair in the Protestant Church is a contemptuous attitude towards past creeds and confessions and the historical battles against heresies. When, for example, there are fundamentalistic defenders of the faith teaching in Bible Colleges, who have not so much as heard of the Canons of Dort or the Synod of Dort, but would lash out at hyper-Calvinism, then you know that something is seriously wrong within the camp. -

Inaugural Lecture

WTJ 70 (2008): 1-18 INAUGURAL LECTURE RAGE, RAGE AGAINST THE DYING OF THE LIGHT CARL R. TRUEMAN I. Introduction Having been unable to find a suitable quotation from Bob Dylan as a title for my inaugural lecture, I have chosen instead a line from a famous poem by his partial namesake, Dylan Thomas. The whole stanza reads as follows: Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. My reason for choosing as my opening shot Dylan Thomas’s rant against the passive resignation of old age in the face of death is simply this: today, both old age and church history are generally regarded as irrelevant. In a culture obses- sed with youth and driven by consumption, old age is something of an embar- rassment. It is an unproductive, unmarketable concept; and, in a church which so often apes the larger culture, church history is usually regarded as having little or nothing of use to say. My purpose, therefore, is to cast a critical eye on this assumption, and to indicate that Westminster Seminary church historians are not simply going to acquiesce in the consensus concerning their irrelevance, but that they fully intend to rage, rage against the dying of the historical light.1 A variety of factors contribute to the anti-historical thrust of the modern age, as I have argued elsewhere.2 Suffice it to say today, however, that I believe that in a society dominated by ideologies of novelty and innovation—ideologies driven by the agendas of science, capital, and consumerism—the past will always be cast in terms which put it at a disadvantage in relation to present and future. -

Textual Notes on Lorenzo Valla's De Falso

H U M A N I S T I C A L O V A N I E N S I A JOURNAL OF NEO-LATIN STUDIES Vol. LX - 2011 LEUVEN UNIVERSITY PRESS Reprint from Humanistica Lovaniensia LX, 2011 - ISBN 978 90 5867 884 3 - Leuven University Press 94693_Humanistica_2011_VWK.indd III 30/11/11 09:27 Gepubliceerd met de steun van de Universitaire Stichting van België © 2011 Universitaire Pers Leuven / Leuven University Press / Presses Uni versitaires de Louvain, Minderbroedersstraat 4 - B 3000 Leuven/Louvain, Belgium All rights reserved. Except in those cases expressly determined by law, no part of this publication may be multiplied, saved in an automated data file or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior written consent of the publishers. ISBN 978 90 5867 884 3 D/2011/1869/39 ISSN 0774-2908 NUR: 635 Reprint from Humanistica Lovaniensia LX, 2011 - ISBN 978 90 5867 884 3 - Leuven University Press 94693_Humanistica_2011_VWK.indd IV 30/11/11 09:27 CONSPECTUS RERUM Fifth Annual Jozef IJsewijn Lecture –– Fidel RÄDLE, Mutianus Rufus (1470/1-1526) – ein Lebensentwurf gegen die Realität . 3-33 1. Textus et studia –– J. Cornelia LINDE, Lorenzo Valla and the Authenticity of Sacred Texts . 35-63 –– Paul WHITE, Foolish Pleasures: The Stultiferae naves of Jodocus Badius Ascensius and the poetry of Filippo Beroaldo the Elder . 65-83 –– Nathaël ISTASSE, Les Gingolphi de J. Ravisius Textor et la pseudohutténienne Conférence macaronique (ca. 1519) 85-97 –– Xavier TUBAU, El Consilium cuiusdam de Erasmo y el plan de un tribunal de arbitraje. 99-136 –– Sergio FERNÁNDEZ LÓPEZ, Arias Montano y Cipriano de la Huerga, dos humanistas en deuda con Alfonso de Zamora. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

The Spanish Match and Jacobean Political Thought, 1618-1624

Opposition in a pre-Republican Age? The Spanish Match and Jacobean Political Thought, 1618-1624 Kimberley Jayne Hackett Ph.D University of York History Department July 2009 Abstract Seventeenth-century English political thought was once viewed as insular and bound by a common law mentality. Significant work has been done to revise this picture and highlight the role played by continental religious resistance theory and what has been termed 'classical republicanism'. In addition to identifying these wider influences, recent work has focused upon the development of a public sphere that reveals a more socially diverse engagement with politics, authority and opposition than has hitherto been acknowledged. Yet for the period before the Civil War our understanding of the way that several intellectual influences were interacting to inform a politically alert 'public' is unclear, and expressions of political opposition are often tied to a pre-determined category of religious affiliation. As religious tension erupted into conflict on the continent, James I's pursuit ofa Spanish bride for Prince Charles and determination to follow a diplomatic solution to the war put his policy direction at odds with a dominant swathe of public opinion. During the last years of his reign, therefore, James experienced an unprecedented amount of opposition to his government of England. This opposition was articulated through a variety of media, and began to raise questions beyond the conduct of policy in addressing fundamental issues of political authority. By examining the deployment of political ideas during the domestic crisis of the early 1620s, this thesis seeks to uncover the varied ways in which differing discourses upon authority and obedience were being articulated against royal government. -

Calvinists Among the Virtues

SCE0010.1177/0953946815570595Studies in Christian EthicsVos 570595research-article2015 Article Studies in Christian Ethics 2015, Vol. 28(2) 201 –212 Calvinists among the © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Virtues: Reformed sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0953946815570595 Theological Contributions to sce.sagepub.com Contemporary Virtue Ethics1 Pieter Vos Protestant Theological University, The Netherlands Abstract Since virtue and the virtues have been important in Reformed theology for most of its history, this essay is devoted to the question of how this tradition may contribute to and interact with contemporary virtue ethics (MacIntyre, Hauerwas). Reformed concepts of sanctification as open to moral growth, covenant as a narrative context of divine commandments, and unio cum Christo as defining human teleology and virtuousness provide valuable contributions to the development of such an ethics. On the other hand, Reformed conceptions of (social) reform, natural law, common grace (Calvin) and christological eschatology (Barth) offer theological arguments for overcoming Hauerwas’s problematic overemphasis on the distinctiveness of the church’s ethic. Keywords Reformed theology, virtue ethics, moral growth, grace, natural virtues It is commonly held that Reformed ethics is basically accomplished as an ethics of divine commandments, creational orders and—to a lesser extent—(human) rights, whereas theological virtue ethics is in particular developed in the Roman Catholic tradition. However, since Elizabeth Anscombe, Alasdair MacIntyre and others initiated a revival of 1. I would like to thank my colleagues Theo Boer, Frits de Lange and Petruschka Schaafsma and other members of the ‘Ethics Colloquium’ at the Protestant Theological University for their helpful remarks on an earlier draft. -

Introduction

Introduction 1 The Synopsis as Handbook of Scholastic Reformed Theology This bilingual edition of the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae makes available for the first time to English readers a seminal treatise of Reformed Scholasticism. Composed by four professors of Leiden University, it gives an exhaustive yet concise presentation of Reformed theology as it was conceived in the first decades of the seventeenth century. During the remainder of the seventeenth century, the Synopsis had a prominent place as a theological handbook for use in training Reformed ministers in the Netherlands. The following Introduction gives a brief sketch of the historical and literary background of the Synopsis. (A more detailed account of the historical and theological contexts will be provided in Volume 3.) Next, an outline is given of the theological topics covered in the first 23 disputations of this volume, and important aspects of scholastic methodology and conceptuality are pointed out. The Introduction closes with some practical features of this edition. Originally the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae consisted of a cycle of public dis- putations held in the Leiden theology faculty from 1620 to 1624.1 In 1596 this fac- ulty had started a cycle of disputations that covered all the topics of Reformed dogmatics, and during the next thirteen years the cycle was repeated five times. After the death of Jacobus Arminius (1609) and the departure of Franciscus Gomarus (1611), the theological faculty of Leiden had been shaken by the eccle- siastical difficulties that would be resolved by the Synod of Dort (1618/19). Fol- lowing Dort’s rejection of the Remonstrant teachings on grace and predestina- tion, the Remonstrant spokesman Simon Episcopius (1583–1643) was removed from his teaching post, and new professors were appointed to join Johannes Polyander (1568–1646), who was then the only professor of theology.