The Nature of God & Predestination in John Davenant's Dissertatio De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanctity and Discernment of Spirits in the Early Modern Period

Angels of Light? Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Edited by Andrew Colin Gow Edmonton, Alberta In cooperation with Sylvia Brown, Edmonton, Alberta Falk Eisermann, Berlin Berndt Hamm, Erlangen Johannes Heil, Heidelberg Susan C. Karant-Nunn, Tucson, Arizona Martin Kaufhold, Augsburg Erik Kwakkel, Leiden Jürgen Miethke, Heidelberg Christopher Ocker, San Anselmo and Berkeley, California Founding Editor Heiko A. Oberman † VOLUME 164 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/smrt Angels of Light? Sanctity and the Discernment of Spirits in the Early Modern Period Edited by Clare Copeland Jan Machielsen LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: “Diaboli sub figura 2 Monialium fraudulentis Sermonibus, conantur illam divertere ab incepto vivendi modo,” in Vita ser. virg. S. Maria Magdalenae de Pazzis, Florentinae ordinis B.V.M. de Monte Carmelo iconibus expressa, Abraham van Diepenbeke (Antwerp, ca. 1670). Reproduced with permission from the Bibliotheca Carmelitana, Rome. Library of Congress Control Number: 2012952309 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1573-4188 ISBN 978-90-04-23369-0 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-23370-6 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Antoine De Chandieu (1534-1591): One of the Fathers Of

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): ONE OF THE FATHERS OF REFORMED SCHOLASTICISM? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2013 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan • 49546-4301 800388-6034 fax: 616 957-8621 [email protected] www. calvinseminary. edu. This dissertation entitled ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): L'UN DES PERES DE LA SCHOLASTIQUE REFORMEE? written by THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: Richard A. Muller, Ph.D. I Date ~ 4 ,,?tJ/3 Dean of Academic Programs Copyright © 2013 by Theodore G. (Ted) Van Raalte All rights reserved For Christine CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1 Introduction: Historiography and Scholastic Method Introduction .............................................................................................................1 State of Research on Chandieu ...............................................................................6 Published Research on Chandieu’s Contemporary -

Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School July 2020 Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789 Stephen Michael Wolfe Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wolfe, Stephen Michael, "Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5344. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5344 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PROTESTANT EXPERIENCE AND CONTINUITY OF POLITICAL THOUGHT IN EARLY AMERICA, 1630-1789 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Stephen Michael Wolfe B.S., United States Military Academy (West Point), 2008 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2016, 2018 August 2020 Acknowledgements I owe my interest in politics to my father, who over the years, beginning when I was young, talked with me for countless hours about American politics, usually while driving to one of our outdoor adventures. He has relentlessly inspired, encouraged, and supported me in my various endeavors, from attending West Point to completing graduate school. -

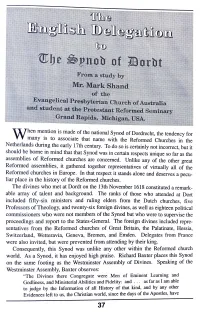

E of the National Synod of Dordrecht, the Tendency for W Many 1S to Associate That Name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands During the Early 17Th Century

hen m~ntion is ma?e of the national Synod of Dordrecht, the tendency for W many 1s to associate that name with the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands during the early 17th century. To do so is certainly not incorrect, but it should be borne in mind that that Synod was in certain respects unique so far as the assemblies of Reformed churches are concerned. Unlike any of the other great Reformed assemblies, it gathered together representatives of virtually all of the Reformed churches in Europe. In that respect it stands alone and deserves a pecu liar place in the history of the Reformed churches. The divines who met at Dordt on the 13th November 1618 constituted a remark able array of talent and background. The ranks of those who attended at Dort included fifty-six ministers and ruling elders from the Dutch churches, five Professors of Theology, and twenty-six foreign divines, as well as eighteen political commissioners who were not members of the Synod but who were to supervise the proceedings and report to the States-General. The foreign divines included repre sentatives from the Reformed churches of Great Britain, the Palatinate, Hessia, Switzerland, Wetteravia, Geneva, Bremen, and Emden. Delegates from France were also invited, but were prevented from. attending by their king. Consequently, this Synod was unlike any other within the Reformed church world. As a Synod, it has enjoyed high praise. Richard Baxter places this Synod on the same footing as the Westminster Assembly of Divines. Speaking of the Westminster Assembly, Baxter observes: "The Divines there Congregate were Men of Eminent Learning and Godliness, and Ministerial Abilities and Fidelity: and . -

Justifying Religious Freedom: the Western Tradition

Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition E. Gregory Wallace* Table of Contents I. THESIS: REDISCOVERING THE RELIGIOUS JUSTIFICATIONS FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM.......................................................... 488 II. THE ORIGINS OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN EARLY CHRISTIAN THOUGHT ................................................................................... 495 A. Early Christian Views on Religious Toleration and Freedom.............................................................................. 495 1. Early Christian Teaching on Church and State............. 496 2. Persecution in the Early Roman Empire....................... 499 3. Tertullian’s Call for Religious Freedom ....................... 502 B. Christianity and Religious Freedom in the Constantinian Empire ................................................................................ 504 C. The Rise of Intolerance in Christendom ............................. 510 1. The Beginnings of Christian Intolerance ...................... 510 2. The Causes of Christian Intolerance ............................. 512 D. Opposition to State Persecution in Early Christendom...... 516 E. Augustine’s Theory of Persecution..................................... 518 F. Church-State Boundaries in Early Christendom................ 526 G. Emerging Principles of Religious Freedom........................ 528 III. THE PRESERVATION OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION EUROPE...................................................... 530 A. Persecution and Opposition in the Medieval -

The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip Van Limborch: a Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism

The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip van Limborch: A Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism By John Mark Hicks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Westminster Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy 1985 Faculty Advisor: Dr. Richard C. Gamble Second Faculty Reader: Mr. David W. Clowney Chairman, Field Committee: Dr. D. Claire Davis External Reader: Dr. Carl W. Bangs 2 Dissertation Abstract The Theology of Grace in the Thought of Jacobus Arminius and Philip van Limborch: A Study in the Development of Seventeenth Century Dutch Arminianism By John Mark Hicks The dissertation addresses the problem of the theological relationship between the theology of Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609) and the theology of Philip van Limborch (1633-1712). Arminius is taken as a representative of original Arminianism and Limborch is viewed as a representative of developed Remonstrantism. The problem of the dissertation is the nature of the relationship between Arminianism and Remonstrantism. Some argue that the two systems are the fundamentally the same, others argue that Arminianism logically entails Remonstrantism and others argue that they ought to be radically distinguished. The thesis of the dissertation is that the presuppositions of Arminianism and Remonstrantism are radically different. The thesis is limited to the doctrine of grace. There is no discussion of predestination. Rather, the thesis is based upon four categories of grace: (1) its need; (2) its nature; (3) its ground; and (4) its appropriation. The method of the dissertation is a careful, separate analysis of the two theologians. -

Jan Krans, Beyond What Is Written: Erasmus and Beza As Conjectural Critics of the New Testament

124 Reviews / ERSY 29 (2009) 103–143 Jan Krans, Beyond What Is Written: Erasmus and Beza as Conjectural Critics of the New Testament. New Testament Tools and Studies 35 (Leiden: Brill, 2006). viii, 384 pp. ISBN 978-90-04-15286-1. Jan Krans’ book is a reworking of his 2004 doctoral thesis, completed under the supervision of Professor Martin de Boer at the Faculty of Theology, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam. A specialist in New Testament exegesis, Krans offers a careful study of how Erasmus and Theodore Beza worked to produce their critical editions of the sacred text. Of great importance for Krans’ study is an analysis of the textual conjectures in their exegesis of the New Testament. The appeal of this approach, of interest not only to biblical scholars but also to those studying humanism, is that it illuminates Erasmus’ and Beza’s methodologies. Above all, Krans is interested in the grounds on which these scholars chose their proposed readings. Indeed, looking beyond the received text and the conjectures, too often studied in and for themselves, Krans seeks to study the hermeneutical foundations of the texts and the conditions under which they were produced. The choice of Erasmus and Beza are natural ones, as both are foundational to modern editions of the New Testament. Consequently, Krans is not only interested in their treatment of the Greek text but in the entirety of their biblical work. As the author underlines in the introduction and epilogue, “judgement of conjectures should be preceded by knowledge of their authors” (333). The first section (7–191) is dedicated to the work of Erasmus. -

Theodore Beza on Prophets and Prophecy. in Beza at 500: New Perspectives on an Old Reformer Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (Göttingen)

Balserak, J. (2020). Theodore Beza on Prophets and Prophecy. In Beza at 500: New Perspectives on an Old Reformer Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (Göttingen). Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage at [insert hyperlink] . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ 1 Theodore Beza on Prophets and Prophecy Jon Balserak University of Bristol On August 19, 1564, Theodore Beza described the scene following Jean Calvin’s death a few months earlier: “the following night and the day after as well, there was much weeping in the city. For the body of the city mourned the prophet of the Lord” (CO 21: 45-6). This is not the only time Beza referred to Calvin as a prophet. In his vita Calvini, Beza wrote: “Calvin in the dedication of his Lectures on the prophet Daniel to the French churches declares, in a prophetic voice, that tempestuous and severe trials were hanging over their heads” (CO 21: 91).1 Study of prophets and prophecy in the medieval and reformation eras is hardly new. A myriad number of people—Birgitta of Sweden (Fogelqvist: 1993), Joachim of Fiore (Reeves: 1969; McGinn: 1985), Girolamo Savanarola (Herzig: 2008), Jan Hus (Oberman: 1999, 135- 67; Haberkern: 2016), Martin Luther (Preuss: 1933; Kolb: 1999; Oberman: 1999, 135-67), Ulrich Zwingli (Büsser: 1950, Opitz: 2007, 2: 493-513; Opitz: 2017), Heinrich Bullinger 1 Beza left Lausanne for Geneva in November 1558, see “Le départ de Bèze et son remplacement” (see Beza: 1962, II, Annexe XIV). -

Calvin, Beza, and Amyraut on the Extent of the Atonement

CALVIN, BEZA, AND AMYRAUT ON THE EXTENT OF THE ATONEMENT by Matthew S. Harding Ph.D. (Cand.) Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2013 D. Min. New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, 2009 M. Ed. University of Arkansas, 2008 M.Div. Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1999 B.A. University of Tennessee, 1995 November 29, 2012 CALVIN, BEZA, AND AMYRAUT ON THE EXTENT OF THE ATONEMENT Introduction The question of the extent of Christ’s atonement in John Calvin’s theology, whether he embraced a universalist or particularist understanding, continues to be a perennial debate within contemporary historical theology. Closely linked, the question whether the tradition that bears Calvin’s name today within Reformed theology is the harmless by-product of natural progression and development from Calvin’s seminal thoughts or a gross misrepresentation of a philosophical system that has clearly departed from Calvin’s theological method, also continues to be contested within evangelical academia. The late Brian G. Armstrong, who in his own right reignited the debate in the 1960s concerning the possible departure of the Reformed tradition from Calvin’s theology, essentially pleads in his work, Calvinism and the Amyraut Heresy, for more aggressive Calvin research into the claims and theology of seventeenth century humanist, Moïse Amyraut, who claimed to represent Calvin’s purest theology as opposed to the new orthodox tradition.1 In his penultimate scholarly endeavor, Armstrong contends that 1In Armstrong’s main text, he worked off the initial thesis by Basil Hall (1965) that Orthodox Reformed Theology of the 18th century to present had indeed departed from the more faithful understanding of Calvin’s soteriology, especially concerning the nature of the atonement. -

Remains, Historical & Literary

GENEALOGY COLLECTION Cj^ftljnm ^Ofiftg, ESTABLISHED MDCCCXLIII. FOR THE PUBLICATION OF HISTORICAL AND LITERARY REMAINS CONNECTED WITH THE PALATINE COUNTIES OF LANCASTER AND CHESTEE. patrons. The Right Hon. and Most Rev. The ARCHBISHOP of CANTERURY. His Grace The DUKE of DEVONSHIRE, K.G.' The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of CHESTER. The Most Noble The MARQUIS of WESTMINSTER, The Rf. Hon. LORD DELAMERE. K.G. The Rt. Hon. LORD DE TABLEY. The Rt. Hon. The EARL of DERBY, K.G. The Rt. Hon. LORD SKELMERSDALE. The Rt. Hon. The EARL of CRAWFORD AND The Rt. Hon. LORD STANLEY of Alderlev. BALCARRES. SIR PHILIP DE M ALPAS GREY EGERTON, The Rt. Hon. LORD STANLEY, M.P. Bart, M.P. The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of CHICHESTER. GEORGE CORNWALL LEGH, Esq , M,P. The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of MANCHESTER JOHN WILSON PATTEN, Esq., MP. MISS ATHERTON, Kersall Cell. OTounctl. James Crossley, Esq., F.S.A., President. Rev. F. R. Raines, M.A., F.S.A., Hon. Canon of ^Manchester, Vice-President. William Beamont. Thomas Heywood, F.S.A. The Very Rev. George Hull Bowers, D.D., Dean of W. A. Hulton. Manchester. Rev. John Howard Marsden, B.D., Canon of Man- Rev. John Booker, M.A., F.S.A. Chester, Disney Professor of Classical Antiquities, Rev. Thomas Corser, M.A., F.S.A. Cambridge. John Hakland, F.S.A. Rev. James Raine, M.A. Edward Hawkins, F.R.S., F.S.A., F.L.S. Arthur H. Heywood, Treasurer. William Langton, Hon. Secretary. EULES OF THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. 1. -

Bibliographie Der Schweizergeschichte Bibliographie De L'histoire Suisse Bibliografìa Della Storia Svizzera 2003

Bibliographie der Schweizergeschichte Bibliographie de l’histoire suisse Bibliograf ìa della storia svizzera 2003 Herausgegeben von der Schweizerischen Landesbibliothek, Bern Publiée par la Bibliothèque nationale suisse, Berne Bibliographie der Schweizergeschichte Bibliographie de l’histoire suisse 2003 l’histoire de Bibliographie Schweizergeschichte der Bibliographie Pubblicata dalla Biblioteca nazionale svizzera, Berna Bibliographie der Schweizergeschichte Bibliographie de l’histoire suisse Bibliograf ìa della storia svizzera 2003 Herausgegeben von der Schweizerischen Landesbibliothek, Bern Publiée par la Bibliothèque nationale suisse, Berne Pubblicata dalla Biblioteca nazionale svizzera, Berna 2006 ISSN 0378-4584 Redaktion / Pierre Louis Surchat Rédaction / Schweizerische Landesbibliothek / Bibliothèque nationale suisse Redazione: Hallwylstrasse 15 3003 CH-Bern E-Mail: [email protected] online: www.snl.ch/biblio Vertrieb: BBL, Vertrieb Publikationen, 3003 CH-Bern Telefax 031 325 50 58 E-Mail [email protected] Internet www.bbl.admin.ch/bundespublikationen Diffusion / Diffusione: OFCL, Diffusion publications, 3003 CH-Berne Fax 031 325 50 58 E-Mail [email protected] Internet www.bbl.admin.ch/bundespublikationen Art. Nr. 304.545.d.f.i 10.06 500 157876 III Bemerkungen des Herausgebers Die seit 1913 regelmässig erscheinende Bibliographie der Schweizergeschichte erfasst die im In und Ausland erschienen Publikationen (Monographien, Sammelschriften, Zeitschriftenartikel und Lizenziatsarbeiten auf allen Arten von -

Textual Notes on Lorenzo Valla's De Falso

H U M A N I S T I C A L O V A N I E N S I A JOURNAL OF NEO-LATIN STUDIES Vol. LX - 2011 LEUVEN UNIVERSITY PRESS Reprint from Humanistica Lovaniensia LX, 2011 - ISBN 978 90 5867 884 3 - Leuven University Press 94693_Humanistica_2011_VWK.indd III 30/11/11 09:27 Gepubliceerd met de steun van de Universitaire Stichting van België © 2011 Universitaire Pers Leuven / Leuven University Press / Presses Uni versitaires de Louvain, Minderbroedersstraat 4 - B 3000 Leuven/Louvain, Belgium All rights reserved. Except in those cases expressly determined by law, no part of this publication may be multiplied, saved in an automated data file or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior written consent of the publishers. ISBN 978 90 5867 884 3 D/2011/1869/39 ISSN 0774-2908 NUR: 635 Reprint from Humanistica Lovaniensia LX, 2011 - ISBN 978 90 5867 884 3 - Leuven University Press 94693_Humanistica_2011_VWK.indd IV 30/11/11 09:27 CONSPECTUS RERUM Fifth Annual Jozef IJsewijn Lecture –– Fidel RÄDLE, Mutianus Rufus (1470/1-1526) – ein Lebensentwurf gegen die Realität . 3-33 1. Textus et studia –– J. Cornelia LINDE, Lorenzo Valla and the Authenticity of Sacred Texts . 35-63 –– Paul WHITE, Foolish Pleasures: The Stultiferae naves of Jodocus Badius Ascensius and the poetry of Filippo Beroaldo the Elder . 65-83 –– Nathaël ISTASSE, Les Gingolphi de J. Ravisius Textor et la pseudohutténienne Conférence macaronique (ca. 1519) 85-97 –– Xavier TUBAU, El Consilium cuiusdam de Erasmo y el plan de un tribunal de arbitraje. 99-136 –– Sergio FERNÁNDEZ LÓPEZ, Arias Montano y Cipriano de la Huerga, dos humanistas en deuda con Alfonso de Zamora.