Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the Use of CERF Funds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The making of hazard: a social-environmental explanation of vulnerability to drought in Djibouti Daher Aden, Ayanleh Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 The making of a hazard: a social-environmental explanation of vulnerability to drought in Djibouti Thesis submitted to King’s College London For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ayanleh Daher Aden Department of Geography Faculty of Social Science and Public Policy December 2014 “The key to riding the wave of chaos is not to resist it, but to allow yourself to know you are a part of the energy of chaos, allowing a new form of organization in it, rather than imposing your old system organization upon it. -

Project Proposal to the Adaptation Fund

PROJECT PROPOSAL TO THE ADAPTATION FUND Project/Programme Category: Regular Country/ies: Djibouti Title of Project/Programme: Integrated Water and Soil Resources Management Project (Projet de gestion intégrée des ressources en eau et des sols PROGIRES) Type of Implementing Entity: Multilateral Implementing Entity Implementing Entity: International Fund for Agricultural Development Executing Entity/ies: Ministry of Agriculture, Water, Fisheries and Livestock Amount of Financing Requested: 5,339,285 (in U.S Dollars Equivalent) i Table of Contents PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION ......................................................................... 1 A. Project Background and Context ............................................................................. 1 Geography ............................................................................................... 1 Climate .................................................................................................... 2 Socio-Economic Context ............................................................................ 3 Agriculture ............................................................................................... 5 Gender .................................................................................................... 7 Climate trends and impacts ........................................................................ 9 Project Upscaling and Lessons Learned ...................................................... 19 Relationship with IFAD PGIRE Project ....................................................... -

Planning and Implementing Ecosystem Based Adaptation (Eba) in Djibouti’S Dikhil and Tadjourah Regions

5/6/2020 WbgGefportal Project Identification Form (PIF) entry – Full Sized Project – GEF - 7 Planning and implementing Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) in Djibouti’s Dikhil and Tadjourah regions Part I: Project Information GEF ID 10180 Project Type FSP Type of Trust Fund LDCF CBIT/NGI CBIT NGI Project Title Planning and implementing Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) in Djibouti’s Dikhil and Tadjourah regions Countries Djibouti Agency(ies) UNEP Other Executing Partner(s) Executing Partner Type Ministry of Habitat, Urbanism, and Environment Government GEF Focal Area Climate Change Taxonomy Biodiversity, Biomes, Climate Change, Climate Change Adaptation, Focal Areas, Sustainable Land Management, Land Degradation, Land Degradation Neutrality, Private Sector, Type of Engagement, Civil Society, Stakeholders, Communications, Gender Mainstreaming, Gender Equality, Gender results areas, Food Security in Sub-Sahara Africa, Integrated Programs, Sustainable Cities, Capacity, Knowledge and Research, Knowledge Generation, Food Security, Land Productivity, Income Generating Activities, Community-Based Natural Resource Management, Sustainable Livelihoods, Sustainable Agriculture, Improved Soil and Water Management Techniques, Ecosystem Approach, Drought Mitigation, Wetlands, Least Developed Countries, Livelihoods, Mainstreaming adaptation, Climate resilience, Community-based adaptation, Ecosystem-based Adaptation, Beneficiaries, Participation, Information Dissemination, Consultation, Behavior change, Awareness Raising, Public Campaigns, SMEs, Community Based -

Download the Project Brief

Consulting services to support IGAD with the implementation of the Regional Migration Fund Supporting migrants, refugees, and host communities in the Horn of Africa and Nile Valley region NIRAS supports the Regional Migration Fund with its aim to create economic opportunities, improve living conditions, and promote social cohesion among the high number of displaced people in the region, as well as locals affected by their arrival. The two towns of the same name - Moyale in Kenya and Moyale in Ethiopia - are located on the main transport route from Addis Ababa to Nairobi, and make up a vibrant transport, trade, and services hub. The Horn of Africa and Nile Valley region comprises FMU, which is responsible for the setup, operation, the countries of Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, So- and management of the RMF, the preparation and malia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Uganda and has a selection of specific interventions, and support to in- population of more than 250 million people. To- dividual measures at project level. gether, these eight countries have established the Tor Jorgensen trade bloc the Intergovernmental Authority on De- RMF projects take place within two investment Project Manager velopment (IGAD). Its aim is to assist and comple- windows. Investment Window 1 (IW1) aims to promo- T: +255 7456 63377 [email protected] ment Member States’ national efforts through in- te local economic development and employment creased cooperation, enhanced food security an growth, improve migrant and host community liveli- environmental protection, improved peace and hoods and strengthen social cohesion, e.g. though security and humanitarian affairs; and promotion of dialogue forums, conflict resolution mechanisms, economic cooperation and integration. -

Water Resource Situation of the Republic of Djibouti

Water resource situation of the Republic of Djibouti Omar ASSOWE DABAR Integrating Groundwater Management within River Basins 15-17 January 2019 Nairobi, Kenya Regional Training Workshop on Integrating Groundwater Management : 15-17 January 2019, Nairobi, Kenya Introduction ❖ The Republic of Djibouti (23 000 km2) is localized in the Horn Africa. ❖70% of the population live in urban areas, 58% live in the capital (Djibouti city). ❖ Djibouti is an arid country which receives, on average, 150 mm of rain annually and has no permanent source of surface water. ❖ Access to water in Djibouti is a major challenge for the development of socio- economic activities. ❖ Harnessing surface and groundwater to improve access to drinking water for vulnerable populations is a Government priority Integrating Groundwater Management : 15-17 January 2019, Nairobi, Kenya 2 Geological situations ❑ Geological Setting ❖ The republic of Djibouti is one of several African countries located on the East African Rift System (EARS). ❖ About 90% of the geological formations are volcanic rocks and 10% are sedimentary formations. ❖ The groundwater in Djibouti is controlled by volcanic and sedimentary aquifers. Volcanic aquifers systems are mainly represented by the Dalha basalts, the stratoid basalts and the Mabla rhyolites. Dalha basalts sequence Coastal plain sediments Integrating Groundwater Management : 15-17 January 2019, Nairobi, Kenya 3 Climatological conditions ❖ The Republic of Djibouti is characterized by arid to semiarid climate. Two seasons predominate : - Cool season (winter) from October to April (20 °C and 30 °C ) - Hot season (summer) from May to September (30 °C and 45 °C) with high rate of Evapotranspiration amounting to 2000 mm per year Précipitation trends (1960 – 1990) 350 HOLL HOLL 300 250 200 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 180 Précipitation (mm) 170 DIKHIL 160 150 140 130 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 ➢ Decrease in rainfall can be observed in different location. -

Djibouti 2013

APPEL GLOBAL DJIBOUTI 2013 Crédit: Jean-Baptiste Tabone DJIBOUTI Appel global 2013 i APPEL GLOBAL DJIBOUTI 2013 Participants au Plan d’Action Humanitaire 2013 à Djibouti C CARE International, Croissant Rouge de Djibouti F FAO, FNUAP H HCR J Johanniter International O OIM, OMS, ONUSIDA P PAM, PNUD U UNICEF, UNOCHA Veuillez noter que les appels sont révisés régulièrement. La dernière version de ce document est disponible sur http ://unocha.org/cap/. Les détails complets des projets sont continuellement mis à jour, et peuvent être consultés, téléchargés et imprimés sur http://fts.unocha.org. ii APPEL GLOBAL DJIBOUTI 2013 TABLE DES MATIERES 1. RESUME ................................................................................................................................... 1 Tableau de bord humanitaire ........................................................................................................ 2 Table I: Besoins par groupe sectoriel ....................................................................................... 4 Table II: Besoins par niveau de priorité ..................................................................................... 4 Table III: Besoins par agence ..................................................................................................... 5 2. REVUE DE L’ANNEE 2012 ....................................................................................................... 6 Réalisation des objectifs stratégiques de 2012 et leçons retenues ............................................. 6 -

As of 17 April 2020, the Ministry of Health Has Confirmed 732 Cases Of

IOM Djibouti is continuing to provide assistance for stranded migrants inside and gloves) at checkpoints, border COVID-19 prevention and response the country due to border closures in crossings and medical centres. support in the form of donations, Ethiopia and Yemen. The Mission is also in discussion with the capacity building to medical staff and The Organization is working closely with Ministry of Women and Family to government officials, and awareness the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry provide COVID-19 protection services raising on proper hygiene practices for of Health and distributing hygiene and to street children in Djibouti city. migrants and host communities. protection non-food items (soap, IOM is also providing multi-sectoral disinfectant, handwashing stations, masks As of 17 April 2020, the Ministry of Health has confirmed 732 COVID-19 on the economy, on 14 April, the Ports and Free cases of COVID-19 in Djibouti and two deaths. In the Balbala Zones Authority decided to grant a 82.5% reduction in port suburb in Djibouti, Al Rahma hospital has become a new tariffs for 60 days to all Ethiopian exports. This gesture in critical epicentre of epidemic. The establishment has been put in time was welcomed by the Ethiopian Prime Minister. The quarantine since by the Ministry of Health. The Government of Government confirmed that the road corridor to Ethiopia will Djibouti has reported testing 7,486 individuals and continues to remain open. All terminal handling charges will be free for strategically target people who have potentially come into Ethiopian exporters for 60 days, as a COVID-19 solidarity contact with those who tested positive for COVID-19. -

Environmental Management of Assal-Fiale Geothermal Project in Djibouti: a Comparison with Geothermal Fields in Iceland

Orkustofnun, Grensasvegur 9, Reports 2015 IS-108 Reykjavik, Iceland Number 7 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT OF ASSAL-FIALE GEOTHERMAL PROJECT IN DJIBOUTI: A COMPARISON WITH GEOTHERMAL FIELDS IN ICELAND Ali Barreh Adaweh Ministry of Energy in charge of Natural Resources Cite Ministerielle, Djibouti REPUBLIC OF DJIBOUTI [email protected] ABSTRACT The geological characteristics of the Assal rift are favourable for the development of geothermal energy in Djibouti. The Government plans to exploit the geothermal resources in the Assal region to enable public access to a reliable, renewable and affordable source of energy. The Assal-Fiale geothermal project is located on a site that has scientific, ecological and tourist importance. Using the geothermal resource is believed to be a positive way to generate electricity in the area but improper management of the resource can cause possible negative impacts on the environment. Environmental impacts assessment will help to understand and minimize negative impacts of the project and with good management can support the environmental, economic and social goals of sustainability. This report presents the possible environmental impacts of the project and their management which aims to minimize them in accordance with national and international regulations and the geothermal utilization experience gained in Iceland. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose of this study The geothermal potential in Djibouti is estimated around 1000 MWe, distributed among thirteen sites and mainly located in the Lake Assal region. The government’s plans, with its first geothermal project, are to exploit the geothermal resources in the Lake Assal region to enable public access to a reliable, renewable and affordable source of energy. -

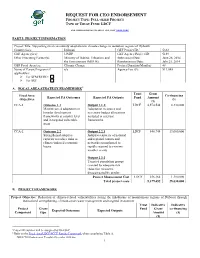

Request for Ceo Endorsement Project Type: Full-Sized Project Type of Trust Fund: Ldcf

REQUEST FOR CEO ENDORSEMENT PROJECT TYPE: FULL-SIZED PROJECT TYPE OF TRUST FUND: LDCF FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT GEF, VISIT THEGEF.ORG PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Supporting rural community adaptation to climate change in mountain regions of Djibouti Country(ies): Djibouti GEF Project ID:1 5332 GEF Agency(ies): UNDP GEF Agency Project ID: 5189 Other Executing Partner(s): Ministry of Habitat, Urbanism and Submission Date: June 26, 2014 the Environment (MHUE) Resubmission Date: July 25, 2014 GEF Focal Area (s): Climate Change Project Duration(Months) 48 Name of Parent Program (if n/a Agency Fee ($): 511,048 applicable): For SFM/REDD+ For SGP A. FOCAL AREA STRATEGY FRAMEWORK2 Trust Grant Focal Area Co-financing Expected FA Outcomes Expected FA Outputs Fund Amount Objectives ($) ($) CCA-1 Outcome 1.1 Output 1.1.1: LDCF 4,574,544 8,330,000 Mainstreamed adaptation in Adaptation measures and broader development necessary budget allocations frameworks at country level included in relevant and in targeted vulnerable frameworks areas CCA-2 Outcome 2.2 Output 2.2.1 LDCF 548,744 19,000,000 Strengthened adaptive Adaptive capacity of national capacity to reduce risks to and regional centers and climate-induced economic networks strengthened to losses rapidly respond to extreme weather events Output 2.2.2 Targeted population groups covered by adequate risk reduction measures, disaggregated by gender. Project Management Cost LDCF 256,164 1,300,000 Total project costs 5,379,452 28,630,000 B. PROJECT FRAMEWORK Project Objective: Reduction of climate-related vulnerabilities facing the inhabitants of mountainous regions of Djibouti through institutional strengthening, climate-smart water management and targeted investment Trust Indicative Indicative Project Grant Fund Grant co-financing Expected Outcomes Expected Outputs Component type Amount ($) ($) 1Project ID number will be assigned by GEFSEC. -

DEVELOPMENT of FISHING and FISHERIES in DJIBOUTI Mid

DEVELOPMENT OF FISHING AND FISHERIES IN DJIBOUTI Mid-Project Report On Resources Development Associates Technical Assistance Contract Prepared By: Paul A. DeRito Dee W. McFadden Robert W. Campbell Keith W. Cox August 1982 Resources Development Associates, P. O. Box 407, Diamond Springs, CA 95619 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report has been prepared by Resources Development Associates for the united States Agency for International Development under Contract Number AID/afr-C-1630. Paul A. DeRito, Project Manager, contributed the majority of the information related to progress of the project to date, with special emphasis on cooperative development, surveys of marketing, production and harvesting, wholesale and retail distribution, fish handling and storage, and relationship to other donor activities. Mr. Dee W. McFadden prepared sections on fishing techniques, training, and boat building. Mr. Keith W. Cox developed the oyster culture program, and Mr. Robert W. Campbell provided background information, scheduling, and editing. This project could not have progressed this far without the interest and assistance of several key persons and offices of the Government of Djibouti, foreign donors, and USAID. These persons include Mr. Mohamed Moussa Chehem (Chief of Service, Livestock and Fisheries Service, Ministry of Agriculture), Mr. E. A. Amundson (AID Affairs Officer, USAID/ Djibouti), Mr. L. Bourassa (Catholic Relief Services, Djibouti), Mr. Ibrahim Dini (Director, ACPM), Mr. L. Pairel (Coordinator, IFAD), Mr. R. Tello (Technical Advisor, FAC), and Mr. Boulesteix (Chief Technical Advisor, Livestock and Fisheries Service, MOA) • i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i ACRONYMS viii 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................•............... 1 1.1 Proj ect Goals 2 1.2 Progress to Date ..............•............. 5 1. -

12325924 03.Pdf

Projet de Renforcement de la Capacité de Transport Maritime entre Djibouti et Tadjourah Rapport de l’étude préparatoire NATURAL CONDITIONS SURVEY PACKAGE-B PREPARATORY SURVEY ON REINFORCEMENT OF MARITIME TRANSPORT AT GOLF OF TADJOURAH FINAL REPORT DJIBOUTI AND TADJOURAH PORTS REPUBLIC OF DJIBOUTI Prepared for : JICA STUDY TEAM In joint venture 1 Issue for approval O. VICAIRE J. GASSANI 12/10/2018 Rev Description Prepared Checked Approuved Date : Tableofcontents 1 Overview ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Intervention date ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Description .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Materials ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Satellite receivers................................................................................................................................................ 6 Mono Beam and Sub Bottom.............................................................................................................................. 6 ADCP................................................................................................................................................................... -

Djibouti Situation Report December 2018

DJIBOUTI SITUATION REPORT DECEMBER 2018 DJIBOUTI Refugee children in Refugee children – Humanitarian Situation Report . Addeh camp Addeh - © UNICEF/Djibouti/Duquenoy © UNICEF/Djibouti/Duquenoy Ali HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION IN NUMBERS • In response to the cyclone Sagar in May, UNICEF distributed Immediate Response WASH and dignity kits benefitting 700 affected households December 2018 (including IDPs and surrounding host community) in Damerjog, an IDP site located just outside Djibouti; 134,000 • UNICEF provided supplies (antibiotics, oral rehydration salts, and zinc) # of children affected out of benefiting an estimated 5,854 children to address the increased caseload 244,920 of pneumonia and diarrhoea linked with deteriorating community-based # of people affected health services (reduced community-based prevention, detection and (OCHA, January 2018) treatment of child illnesses in favour of secondary and tertiary care). 13,330 • UNICEF and the Red Crescent of Djibouti conducted a large-scale hygiene # of children affected out of promotion campaign with more than 25,000 people being reached on 28,778 handwashing and household water treatment practices through multiple # of refugees and asylum seekers channels (SMS, face-to-face). (UNHCR, Dec 2018) • An estimated 4,500 refugee and migrant children were enrolled in the 4,910 Read, Write and Count (RWC) second-chance education. # of refugees and asylum seekers in Djibouti-city (UNHCR, Dec. 2018) UNICEF Appeal 2018: US$ 1.641 million Funding Status: UNICEF Sector/Cluster UNICEF’s Response with