Sino-Israeli Relations: Current Reality and Future Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Ana Israel: From

China ana Israel: From Not only is the title of this book rem aspects of the evolving relations history of this partnership, see Yoram iniscent of Agnon's story From Foe to between Israel and China. In their Evron's essay Economics, Science Friend (1941 ), its topic also seems to essay, Shichor and Merhav divide and Tecbnology in the Israel-China be similar: the attempts of the Jewish these relations into four stages: Relations. state to befriend a huge and power Drought (1949-1978), Tillage (1979 Economic aspects are just one of ful enemy. The struggle bears fruit 1984), Seedtime (1985-1991) and many areas covered by From Dis only towards the end of the story, as Harvest (1992.) cord to Concord. Other essays, such the permanence of the protagonist's In actual fact, the optimistic picture as 1991: A Decisive Year, written by presence is acknowledged. described in the book has been sur Zeev Sufott (who passed away in Relations between China and Israel passed by reality, with many econ 2014), describe the development have improved greatly over the last omists forecasting that China will of diplomatic relations between 67 two decades, to such an extent that soon outdo the US as Israel's larg the two countries. Sufott details even this recent and updated col est trading partner. Thus recent years the titanic efforts that took place lection of essays inevitably fails to are a fifth phase that might be called throughout 1991, culminating in the cover some cardinal events. "The Boom". establishment of relations between China and Israel: From Discord to Suffice to say that during the first Israel and both China and India .Concord was edited by two fellow half of last year, China invested during one momentous week in members of the SJI International more than $2 billion in Israel, com 1992. -

Campdavid Article Jan 15

Evidence of Polythink?: The Israeli Delegation at Camp David 2000 Alex Mintz Yale University & Texas A&M University Shaul Mishal Tel Aviv University Nadav Morag Tel Aviv University January 2003 * The authors thank former Israeli Foreign Minister Professor Shlomo Ben- Ami, former IDF Chief of Staff, Lt. General (res.) Amnon Lipkin-Shachak, ex-Cabinet Minister Dan Meridor, former Chief of the IDF Planning Division, Major-General (res.) Shlomo Yanai, former adviser to Ehud Barak, Attorney Gilad Sher, former head of the Israeli Mossad, Dani Yatom, former Foreign Ministry Director-General, Reuven Merhav, former Deputy- Director of the Israel Security Agency, Israel Hason, and Deputy-Director of the Israeli Foreign Ministry, Dr. Oded Eran for their participation in this study. Abstract The concept of Groupthink advanced by Janis some twenty years ago (1982) and further articulated, refined and tested by Smith (1984), places a premium on conformity of group members to group views, opinions and decisions, due to peer pressure, social cohesion of the group, self-censorship and variety of other factors (Janis 1982). According to Janis (ibid), one of the consequences of Groupthink is defective or “bad” decision-making. This paper introduces the concept of Polythink, which is essentially the opposite of Groupthink: a plurality of opinions, views and perceptions of group members. We show how one can measure Polythink. We then report decision-theoretic results based on qualitative, face-to-face interviews with the actual members of the Israeli delegation to the peace negotiations at Camp David 2000, to determine whether there was evidence of group conformity and uniformity among members of the Israeli delegation that led to the collapse of the talks or whether there is evidence for Polythink. -

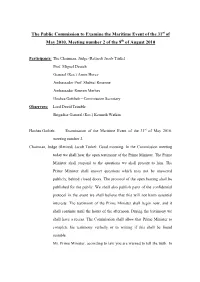

Turkel Commission Protocol

The Public Commission to Examine the Maritime Event of the 31st of May 2010, Meeting number 2 of the 9th of August 2010 Participants: The Chairman, Judge (Retired) Jacob Turkel Prof. Miguel Deutch General (Res.) Amos Horev Ambassador Prof. Shabtai Rosenne Ambassador Reuven Merhav Hoshea Gottlieb – Commission Secretary Observers: Lord David Trimble Brigadier General (Res.) Kenneth Watkin Hoshea Gotlieb: Examination of the Maritime Event of the 31st of May 2010, meeting number 2. Chairman, Judge (Retired) Jacob Turkel: Good morning. In the Commission meeting today we shall hear the open testimony of the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister shall respond to the questions we shall present to him. The Prime Minister shall answer questions which may not be answered publicly, behind closed doors. The protocol of the open hearing shall be published for the public. We shall also publish parts of the confidential protocol in the event we shall believe that this will not harm essential interests. The testimony of the Prime Minister shall begin now, and it shall continue until the hours of the afternoon. During the testimony we shall have a recess. The Commission shall allow that Prime Minister to complete his testimony verbally or in writing if this shall be found suitable. Mr. Prime Minister, according to law you are warned to tell the truth. In your testimony I shall ask you to refer to the main issues before the Commission. Did the blockade imposed on the Gaza Strip and the steps taken to enforce it comply with the rules of International Law? Afterwards, I will continue with the other main questions. -

The Evolution of Israeli-Chinese Friendship the S

The S. Daniel Abraham Center for International and Regional Studies Confucius Institute Prof. Aron Shai is the Rector (Provost) of Tel Aviv University and the incumbent of the Shoul N. Eisenberg Chair for East Asian Affairs. He is a well known authority in East Asian studies, the author of ten books and The Evolution of the editor of many others. He has published over 50 articles in academic journals. Israeli-Chinese Friendship His two recent books on the fate of foreign firms in China and the biography of Marshal Zhang Xue-Liang have been published in Hebrew, Aron Shai English and Chinese. His works on China and Israel appeared in several countries. Aron Shai also published two historical novels. Prof. Shai teaches modern history, Chinese contemporary history and political economy at Tel Aviv University. He was a Guest Professor at St. Antony's College and Mansfield College, Oxford; University of Toronto; École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris; East-Asian Institute, Columbia University, New York; New York University, and the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. Shai is a frequent visitor at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences and various institutions of higher education in China. Research Paper 7 The S. Daniel Abraham Center for International and Regional Studies Confucius Institute Aron Shai The Evolution of Israeli-Chinese Friendship The S. Daniel Abraham Center for International and Regional Studies Established in 2004 by Tel Aviv University, the S. Daniel Abraham Center for International and Regional Studies promotes collaborative, interdisciplinary scholarship and teaching on issues of global importance. Combining the activities and strengths of Tel Aviv University's professors and researchers in various disciplines, the Abraham Center aims to integrate international and regional studies at the University into informed and coherent perspectives on global affairs. -

Turkel Commission to Examine the Maritime Incident

The Public Commission Investigating the Maritime Incident of the 31st of May 2010 (Turkel Commission) Meeting number 12, of the 13th of October 2010 Participants: Chairman, Judge (ret.) Jacob Turkel Prof. Miguel Deutsch General (ret.) Amos Horev Ambassador Reuven Merhav Observers: Lord David Trimble Brig. Gen. (ret.) Kenneth Watkin Commission Coordinator, Hoshea Gottlieb Witnesses: Representatives of Betzelem: Jessica Montel, Eyal Hareuveni. Representatives of Doctors for Human Rights: Prof. Tzvi Bentowitz, Ran Yaron, Dr. Mustafa Yassin. Representatives of the Gisha organization: Adv. Tamar Feldman, Adv. Sari Beshi The Chairman, Judge (ret.) Jacob Turkel: Ms. Feldman. Who else? The Gisha organization, Adv. Sari Beshi: Adv. Sari Beshi. The Chairman, Judge (ret.) Jacob Turkel: Are you also testifying before us? The Gisha organization, Adv. Sari Beshi: I will sit beside her. The Chairman, Judge (ret.) Jacob Turkel: Good. Ms. Feldman, you are warned to state the truth, and we would like to hear you regarding the humanitarian situation in Gaza, insofar as you know, and in particular, in relation to the actions of the system for transferring cargo between the Gaza Strip, between Israel and Gaza. If you please. The Gisha organization, Adv. Tamar Feldman: Good afternoon. My name is Tamar Feldman. I am the director of the legal department at the Gisha organization. The Gisha organization in a few words, is a registered non-profit organization in Israel which was established by Adv. Sari Beshi, who is the CEO of the organization today as well, together with Prof. Kenneth Mann. The organization deals with the promotion of human rights in Israel and in the territories under Israel’s control, and mainly deals with legal and public activities whose aim is the protection of the right to freedom of movement and the various rights connected with access to resources for protected Palestinian residents who live in the territories, and particularly in Gaza. -

Peace Talks on Jerusalem a Review of the Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations Concerning Jerusalem 1993-2013

The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Peace Talks on Jerusalem A Review of the Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations Concerning Jerusalem 1993-2013 Lior Lehrs The JIIS Series no. 432 Peace Talks on Jerusalem A Review of the Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations Concerning Jerusalem 1993-2013 Lior Lehrs © 2013, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St. 92186 Jerusalem http://www.jiis.org.il E-mail:[email protected] About the Author Lior Lehrs is a researcher at the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. He is a doctoral student at the Department of International Relations of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The topic of his PhD research is “Private Peace Entrepreneurs in Conflict Resolution Processes.” Recent publications include Y. Reiter and L. Lehrs, The Sheikh Jarrah Affair, Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2010; L. Lehrs, “Political Holiness: Negotiating Holy Places in Eretz Israel/Palestine, 1937-2003,” in M. Breger, Y. Reiter, and L. Hammer (eds.), Sacred Space in Israel and Palestine: Religion and Politics (London: Routledge, 2012). Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies’ Work Group: Jerusalem between management and resolution of the conflict Since 1993 a Work Group of the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies has been engaged in studying the political future of Jerusalem. The group aims to present policymakers, public-opinion shapers, and the interested public with reliable, up- to-date information about the demographic, social, and political trends in East Jerusalem and in the city as a whole, and to formulate alternatives for management of the city in the absence of a political agreement as well as alternatives for future management. -

The Geography of Sino-Israeli Relations

The Geography of Sino-Israeli Relations Binyamin Tjong-Alvares The People’s Republic of China was formally founded in October 1949, only eleven months after the state of Israel. Although situated on opposite ends of the Asian con- tinent, both nations began as poor, agrarian societies, early in their formation facing many similar challenges such as territorial threats. However, the geographic distance between the Middle Kingdom and the Holy Land, their location vis-à-vis Europe and the West, and their contrasting experience with the former colonial powers deci- sively influenced their world outlook, keeping these two countries at arm’s length for decades. The United States in particular played a decisive role as an impediment to the natural growth of a stronger relationship between these two ancient nations that have much in common. Now, as China and Israel complete the twentieth year of dip- lomatic relations, and as the Sino-Israeli relationship appears more independent from American influence than ever before, the two nations are finally poised to explore the abundance of synergies that bind them through deeper and broader interaction and a shared goal of bringing those benefits to the wider world. Historical Background The Sino-Israeli bond antedated the official establishment of either state in the wake of World War II. As early as December 1918, Chen Lu, the vice-minister of foreign affairs of the Kuomintang (KMT) government in Nanjing, endorsed the Balfour Declaration, demonstrating a clearly positive attitude of the KMT toward the Jews and Zionism. In April 1920, the Republic of China’s founding father and first president Sun Yat-sen wrote a letter in support of the Jewish resettlement of Palestine. -

Strategic Assessment Vol 15, No 2

Volume 15 | No. 2 | July 2012 “Iran First” or “Syria First”: What Lies between the Iranian and Syrian Crises | Amos Yadlin Egypt after Morsi’s Victory in the Presidential Elections | Shlomo Brom Revival of the Periphery Concept in Israel’s Foreign Policy? | Yoel Guzansky and Gallia Lindenstrauss Authority and Responsibility on the Civilian Front | Meir Elran and Alex Altshuler From Vision to Reality: Tangible Steps toward a Two-State Solution | Gilead Sher A Conceptual Framework and Decision Making Model for Israel about Iran | Amos Yadlin Israel and the Palestinians: Policy Options Given the Infeasibility of Reaching a Final Status Agreement | Shlomo Brom The Uprisings in the Arab World and their Ramifications for Israel | Mark A. Heller Relations between Israel and the United States before and after the Presidential Elections | Oded Eran המכון למחקרי ביטחון לאומי THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURcITY STUDIES INCORPORATING THE JAFFEE bd CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 15 | No. 2 | July 2012 CONTENts Abstracts | 3 “Iran First” or “Syria First”: What Lies between the Iranian and Syrian Crises | 7 Amos Yadlin Egypt after Morsi’s Victory in the Presidential Elections | 19 Shlomo Brom Revival of the Periphery Concept in Israel’s Foreign Policy? | 27 Yoel Guzansky and Gallia Lindenstrauss Authority and Responsibility on the Civilian Front | 41 Meir Elran and Alex Altshuler From Vision to Reality: Tangible Steps toward a Two-State Solution | 53 Gilead Sher Findings and conclusions of INSS working groups, prepared for the 5th Annual International Conference A Conceptual Framework and Decision Making Model for Israel about Iran | 69 Amos Yadlin Israel and the Palestinians: Policy Options Given the Infeasibility of Reaching a Final Status Agreement | 75 Shlomo Brom The Uprisings in the Arab World and their Ramifications for Israel | 83 Mark A. -

The Naval Blockade of the Gaza Strip

The Public Commission to Examine the Maritime Incident of 31 May 2010 The Turkel Commission Report | Part one The Public Commission to Examine the Maritime Incident of 31 May 2010 The Turkel Commission January 2011 Report | Part one The Public Commission to Examine the Maritime Incident of 31 May 2010 Mr. Benjamin Netanyahu The Prime Minister The honorable Prime Minister, Re: Report of the Commission for Examining the Maritime Incident of May 31, 2010 - Part One Pursuant to paragraph 10 of Government resolution no. 1796 of June 14, 2010, we respectfully submit to the Government a report on the following matters: a. The security circumstances in which the naval blockade on the Gaza Strip was imposed and whether the blockade complies with the rules of international law (paragraph 4a of the Government resolution). b. Whether the actions carried out by Israel to enforce the naval blockade on May 31, 2010, complied with the rules of international law (paragraph 4b of the Government resolution). c. The actions carried out by the organizers and participants of the flotilla and their identities (paragraph 4c of the Government resolution). In the next stage, the commission will submit part two of the report, which will address the question whether the mechanism for examining and investigating complaints and claims of violations of the laws of war, as carried out by Israel in general, and as implemented with regard to the events of May 31, 2010, in particular, complies with the obligations of the State of Israel pursuant to the rules of international law. Part two of the report will also address other questions that arose from the material before the commission. -

The Israeli-Palestinian Violent C O N F R O N T a T I O N 2000-2004

The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Teddy Kollek Center for Jerusalem Studies The Israeli-Palestinian Violent Confrontation 2000-2004: From Conflict Resolution to Conflict Management Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov Ephraim Lavie Kobi Michael Daniel Bar-Tal כל הזכויות שמורות למכון ירושלים לחקר ישראל The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Teddy Kollek Center for Jerusalem Studies The Israeli-Palestinian Violent Confrontation 2000-2004: From Conflict Resolution to Conflict Management Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov Ephraim Lavie Kobi Michael Tal־Daniel Bar 2005 כל הזכויות שמורות למכון ירושלים לחקר ישראל The Teddy KoIIek Center for Jerusalem Studies Established by: The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies & The Jerusalem Foundation The JUS Research Series # 102 The Israeli-Palestinian Violent Confrontation 2000-2004: From Conflict Resolution to Conflict Management Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov Ephraim Lavie Kobi Michael Daniel Bar-Tal Translation & Editing: Ralph Mandel This publication was made possible by funds granted by The Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation The Frankel Foundation The Charles H. Revson Foundation The statements made and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. © 2005, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem Israel http://www.jiis.org.il כל הזכויות שמורות למכון ירושלים לחקר ישראל Acknowledgments This study is the product of a joint effort by a "think team" that convened at the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies between September 2003 and December 2004. I want to take this opportunity to thank all the members of the team, each separately and as a group, for the devotion, diligence, and insight they brought to the project, out of a belief in its importance and in the hope that it will contribute to the public discourse. -

Notes and References

Notes and References INTRODUCTION 1. Michael Hudson, The Precarious Republic (Colorado: Westview Press, 1985), p.98. 2. Aaron KJieman, 'Zionist Diplomacy and Israeli Foreign Policy', The Jerusalem Quarterly, No . II , Spring 1979. 3. C.T. Onions (ed.), Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles, Vol.1 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1944). 4. Avi Shlaim , 'Israeli Interference in Internal Arab Politics: The Case of Lebanon', in Giacomo Luciani and Ghassan Salame (eds), The Politics ofArab Integration (London: Croom Helm, 1988), p.232. 1 THE IDEA OF AN ALLIANCE: ISRAELI-MARONITE RELATIONS, 1920s-48 1. Avi Shlaim, Collusion across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), p.235. 2. Le Pere Pierre Raphael, Le CUre du Liban dans l'Histoire (Beirut: Imprimerie Gedeen, 1924). 3. Itamar Rabinovich, The War for Lebanon. 1970-1985, revised edition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), p.21. 4. Hudson, The Precarious Republic, p.44. 5. Ibid, p.94. 6. Iliya Harik, Politics and Changein a Traditional Society: Lebanon 1711- 1845 (princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968), p.128. 7. Interview with Fuad Abu Nader, Beirut, 4 July 1995. 8. Rabinovich, p.21. 9. Interview with Fuad Abu Nader, Beirut, 4 July 1995. 10. Interview with Yossi Olmert, Tel Aviv, 9 November 1993. 11. Treaty of 26 March 1920, S2519907, Central Zionist Archives (CZA). See also Benny Morris, 'Israel and the Lebanese Phalange: The Birth of a Relationship 1948-1951', Studies in Zionism,Vol. 5, No.1, 1984, p. 129. See also Laura Zittrain Eisenberg, 'Desperate Diplomacy: The Zionist-Maronite Treaty of 1946', Studies in Zionism, Vol. -

Turkel Commission Protocol

The Public Commission For Examining The Naval Incident Of 31 May 2 010 (The Turkel Commission) Session Number Three, On 10.08.2010 Participants: The Chairman Justice (Ret.) Jacob Turkel Prof. Miguel Deutch General (Ret.) Amos Horev Amb. Shabtai Rosenne Amb. Reuven Merhav Observers: Lord David Trimble Brigadier General (Ret.) Kenneth Watkin The Secretary to the Commission Hoshea Gottlieb Witness: Defense Minister Ehud Barak Hosea Gottlieb, Secretary to the Commission: The Public Commission for Examining the Naval Incident of 31 May 2010, Session Number Three The Chairman, Justice (Ret.) Jacob Turkel: Good morning, in today's session of the commission we will hear the public testimony of the defense minister. The defense minister will respond to questions directed to him. What cannot be heard publicly, the defense minister will respond, should he so desire, behind closed doors. The protocols of the open deliberation will be made public. To the extent that we believe that it will not damage vital interests, we will also publicize parts of the protocol from the confidential deliberation. The testimony of the defense minister will commence now, and will continue up to the afternoon hours. During the deliberation we will go out for recess. To the extent that it will be considered proper, the commission will allow the defense minister to complete his testimony orally or in writing. Here I want to note, that a supplement will be apparently be needed simply for the reason that we received the materials from the defense ministry only last night. And of course we could not read this by now.