The Geography of Sino-Israeli Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mediterranean Coast of Israel Is a New City,Now Under

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Theses and Major Papers Marine Affairs 12-1973 The editM erranean Coast of Israel: A Planner's Approach Sophia Professorsky University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/ma_etds Part of the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Professorsky, Sophia, "The eM diterranean Coast of Israel: A Planner's Approach" (1973). Theses and Major Papers. Paper 146. This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Marine Affairs at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Major Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. l~ .' t. ,." ,: .. , ~'!lB~'MEDI'1'ERRANEAN-GQAsT ~F.~"IsMt~·;.·(Al!~.oS:-A~PROACH ::".~~========= =~.~~=~~~==b======~~==~====~==.=~=====~ " ,. ••'. '. ,_ . .. ... ..p.... "".. ,j,] , . .;~ ; , ....: ./ :' ",., , " ",' '. 'a ". .... " ' ....:. ' ' .."~".,. :.' , v : ".'. , ~ . :)(A;R:t.::·AF'~~RS'· B~NMi'»APER. '..":. " i . .: '.'-. .: " ~ . : '. ". ..." '-" .~" ~-,.,. .... .., ''-~' ' -.... , . ", ~,~~~~"ed .' bYr. SOph1a,Ji~ofes.orsJcy .. " • "..' - 01 .,.-~ ~ ".··,::.,,;$~ld~~:' ·to,,:" f;~f.... ;)J~:Uexa~d.r . -". , , . ., .."• '! , :.. '> ...; • I ~:'::':":" '. ~ ... : .....1. ' ..~fn··tr8Jti~:·'btt·,~e~Mar1ne.~a1~S·~r~~. ", .:' ~ ~ ": ",~', "-". ~_"." ,' ~~. ;.,·;·X;'::/: u-=" .. _ " -. • ',. ,~,At:·;t.he ,un:lvers:U:~; tif Rh~:<:rs1..J\d. ~ "~.; ~' ~.. ~,- -~ !:).~ ~~~ ~,: ~:, .~ ~ ~< .~ . " . -, -. ... ... ... ... , •• : ·~·J;t.1l9ston.l~~;&:I( .. t)eceiDber; 1~73.• ". .:. ' -.. /~ NOTES, ===== 1. Prior to readinq this paper, please study the map of the country (located in the back-eover pocket), in order to get acquain:t.ed with names and locations of sites mentioned here thereafter. 2.- No ~eqaJ. aspects were introduced in this essay since r - _.-~ 1 lack the professional background for feedinq in tbe information. -

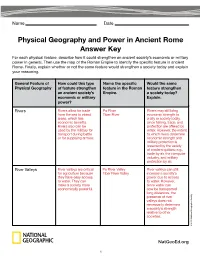

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

ARTICLES Israel's Migration Balance

ARTICLES Israel’s Migration Balance Demography, Politics, and Ideology Ian S. Lustick Abstract: As a state founded on Jewish immigration and the absorp- tion of immigration, what are the ideological and political implications for Israel of a zero or negative migration balance? By closely examining data on immigration and emigration, trends with regard to the migration balance are established. This article pays particular attention to the ways in which Israelis from different political perspectives have portrayed the question of the migration balance and to the relationship between a declining migration balance and the re-emergence of the “demographic problem” as a political, cultural, and psychological reality of enormous resonance for Jewish Israelis. Conclusions are drawn about the relation- ship between Israel’s anxious re-engagement with the demographic problem and its responses to Iran’s nuclear program, the unintended con- sequences of encouraging programs of “flexible aliyah,” and the intense debate over the conversion of non-Jewish non-Arab Israelis. KEYWORDS: aliyah, demographic problem, emigration, immigration, Israel, migration balance, yeridah, Zionism Changing Approaches to Aliyah and Yeridah Aliyah, the migration of Jews to Israel from their previous homes in the diaspora, was the central plank and raison d’être of classical Zionism. Every stream of Zionist ideology has emphasized the return of Jews to what is declared as their once and future homeland. Every Zionist political party; every institution of the Zionist movement; every Israeli government; and most Israeli political parties, from 1948 to the present, have given pride of place to their commitments to aliyah and immigrant absorption. For example, the official list of ten “policy guidelines” of Israel’s 32nd Israel Studies Review, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 2011: 33–65 © Association for Israel Studies doi: 10.3167/isr.2011.260108 34 | Ian S. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

Prevalence of Asthma Among Young Men Residing in Urban Areas with Different Sources of Air Pollution Nili Greenberg Phd1,3, Rafael S

,0$-ǯ92/21ǯ'(&(0%(52019 ORIGINAL ARTICLES Prevalence of Asthma among Young Men Residing in Urban Areas with Different Sources of Air Pollution Nili Greenberg PhD1,3, Rafael S. Carel MD DrPH1, Jonathan Dubnov MD MPH1, Estela Derazne MSc3 and Boris A. Portnov PhD DSc2 1School of Public Health and 2Department of Natural Resources and Environment Management, University of Haifa, Israel 3Israeli Defense Forces, Medical Corps, Israel data used in different studies. Two studies by Greenberg and ABSTRACT: Background: Asthma is a common respiratory disease, which colleagues [6,7], which were based on individual data obtained is linked to air pollution. However, little is known about the for a large nation-wide cohort of young men, demonstrated effect of specific air pollution sources on asthma occurrence. higher prevalence rates of asthma in more polluted areas. Objective: To assess individual asthma risk in three urban The studies also showed a statistically significant association areas in Israel characterized by different primary sources of air between asthma risk and residential exposure to nitrogen diox- pollution: predominantly traffic-related air pollution (Tel Aviv) ide (NO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) air pollutants. However, or predominantly industrial air pollution (the Haifa bay area little is known about the effect of specific sources of air pollu- and Hadera). tion on asthma prevalence. Methods: The medical records of 13,875, 16- to 19-year-old males, who lived in the affected urban areas prior to their BACKGROUND STUDIES army recruitment and who underwent standard pre-military Air pollution from motor traffic and industries is significantly health examinations during 2012–2014, were examined. -

THE LYCIAN PEOPLE and THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography And

CHAP'IERTWO THE LYCIAN PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography and communications in Lycia1 Lycia lies on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, between Caria and Pam phylia. At the period of its smallest extent, at the time of the Persian con quest, the Lycian state covered an area comparable in size to Attica, ex tending over most of the territory of the Xanthos valley, probably as far north as Araxa, more than forty kilometres away from Xanthos, and nearly fifty from the Mediterranean; Bryce has argued that to Homer 'Lycia' meant no more than the Xanthos valley. 2 At its largest, under Perikle of Limyra (pp. 154-70), the Lycian state was comparable in size to the south ern Peloponnese (i.e. Laconia and Messenia), stretching from Phaselis in the east to Telemessos in the north-west, nearly a hundred and thirty kilo metres as the crow flies, and included a large section of southern Milyas, if not all of it (p. 20). It is separated from its neighbours by high mountains which hampered movement in antiquity. 3 This remoteness continued into modern times-when Bean first visited the area in 1946 he found a country where tractors were unknown, and: When I asked, 'What do you do in the winter?', the answer was, 'We sit'.4 Three great chains determine access to and within Lycia. In the west two spurs of the western Tauros, the Boncuk Daglan and the Baba Dag1 (this latter being ancient Mt. Kragos and Mt. Antikragos) restrict access to Ly cia to the pass between them, east of Telemessos. -

Download Abstract Book

RESEARCH UPDATE Table of contents 1. Clinical Outcomes Knee Conditions Hip Conditions Lower Back Conditions Ankle Condition 2. Biomechanical Alignment and Perturbation 39 3. Specific Muscle Activation 53 4. Knee Osteoarthritis Functional Severity Classification & Gait Analysis 57 5 Additional Scientific Evidence 63 ¡ Biomechanical aspects of knee osteoarthritis and AposTherapy - Review A. Elbaz (MD), A. Mor (MD), G.Segal AposTherapy Research Group Abstract Over the past few decades, there has been growing evidence on the importance of biomechanical factors in the pathogenesis of knee osteoarthritis (OA). Knee OA is characterized by decreased neuromuscular control, instability of the knee joint and weakness of the knee musculature, all of which lead to abnormal -

Republication, Copying Or Redistribution by Any Means Is

Republication, copying or redistribution by any means is expressly prohibited without the prior written permission of The Economist The Economist April 5th 2008 A special report on Israel 1 The next generation Also in this section Fenced in Short-term safety is not providing long-term security, and sometimes works against it. Page 4 To ght, perchance to die Policing the Palestinians has eroded the soul of Israel’s people’s army. Page 6 Miracles and mirages A strong economy built on weak fundamentals. Page 7 A house of many mansions Israeli Jews are becoming more disparate but also somewhat more tolerant of each other. Page 9 Israel at 60 is as prosperous and secure as it has ever been, but its Hanging on future looks increasingly uncertain, says Gideon Licheld. Can it The settlers are regrouping from their defeat resolve its problems in time? in Gaza. Page 11 HREE years ago, in a slim volume enti- abroad, for Israel to become a fully demo- Ttled Epistle to an Israeli Jewish-Zionist cratic, non-Zionist state and grant some How the other fth lives Leader, Yehezkel Dror, a veteran Israeli form of autonomy to Arab-Israelis. The Arab-Israelis are increasingly treated as the political scientist, set out two contrasting best and brightest have emigrated, leaving enemy within. Page 12 visions of how his country might look in a waning economy. Government coali- the year 2040. tions are fractious and short-lived. The dif- In the rst, it has some 50% more peo- ferent population groups are ghettoised; A systemic problem ple, is home to two-thirds of the world’s wealth gaps yawn. -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

Research on Coastal Cliffs and Beach Erosion in Israel

RREESSEEAARRCCHH OONN CCOOAASSTTAALL CCLLIIFFFFSS AANNDD BBEEAACCHH EERROOSSIIOONN IINN IISSRRAAEELL Dov S. ROSEN Department of Marine Geology & Coastal Processes PROGRESS REPORT Report IOLR H56/2009 Haifa, September 2009 Submitted to MMMrrr... BBBeeerrrtttrrraaammm CCCOOOHHHNNN NNNOOORRRTTTHHH AAAMMMEEERRRIIICCCAAANNN FFFRRRIIIEEENNNDDDSSS OOOFFF IIIOOOLLLRRR i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OBJECTIVES The objectives of this research study are to improve our scientific understanding of the factors affecting the coastal cliffs and beach erosion along the Mediterranean coast of Israel, particularly the future onshore-offshore and alongshore dynamics of waves, currents, sea level rise and sediment transport processes. The progress of the study carried out so far is presented in this progress report. The author and the staff of the Department of Marine Geology and Coastal Processes wish to express our appreciation and thank Mr. Bertram Cohn of North American Friends of IOLR for the funding support provided. RESULTS Main results obtained so far are presented in tables and graphs. They show assessments of the maximum runup of the waves during extreme storm conditions, of the extreme waves and sea levels for return average periods of up to 100 years, results of erosion-accretion balance for the study coast during 1997-2004 period, examples of differential maps of the beach and cliff at Apolonia and near Marina Herzliya between 2002 and 2003 as well as the waterline position changes between 1997 and 2004, and examples of the numerical wave and sedimentological modeling simulations and their outcomes for the study sector – the central sector of the Mediterranean coast of Israel. PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS The work presented in this report is an ongoing study on the coastal erosion at the beach and coastal cliff of a typical coastal sector at the Mediterranean coast of Israel.