David C. Cassidy Wins 2014 Abraham Pais Prize in This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chem 103, Section F0F Unit I

Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Chem 103, Section F0F Nuclear Model of the Atom Unit I - An Overview of Chemistry Dalton’s theory proposed that atoms were indivisible particles. Lecture 4 • By the late 19th century, this aspect of Dalton’s theory was being challenged. • Work with electricity lead to the discovery of the electron, • Some observations that led to the nuclear model as a particle that carried a negative charge. for the structure of the atom • The modern view of the atomic structure and the elements • Arranging the elements into a (periodic) table 2 Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Nuclear Model of the Atom Nuclear Model of the Atom The cathode ray In 1897, J.J. Thomson (1856-1940) studies how cathode rays • Cathode rays were shown to be electrons are affected by electric and magnetic fields • This allowed him to determine the mass/charge ration of an electron Cathode rays are released by metals at the cathode 3 4 Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Lecture 4 - Observations that Led to the Nuclear Model of the Atom Nuclear Model of the Atom In 1897, J.J. Thomson (1856-1940) studies how cathode rays In 1897, J.J. Thomson (1856-1940) studies how cathode rays are affected by electric and magnetic fields are affected by electric and magnetic fields • Thomson estimated that the mass of an electron was less • Thomson received the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physics for his that 1/1000 the mass of the lightest atom, hydrogen!! work. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

Historical Background Prepared by Dr, Robin Chaplin Professor of Power Plant Engineering (Retired) University of New Brunswick

1 Historical Background prepared by Dr, Robin Chaplin Professor of Power Plant Engineering (retired) University of New Brunswick Summary: A review of the historical background for the development of nuclear energy is given to set the scene for the discussion of CANDU reactors. Table of Contents 1 Growth of Science and Technology......................................................................................... 2 2 Renowned Scientists............................................................................................................... 4 3 Significant Achievements........................................................................................................ 6 3.1 Niels Bohr........................................................................................................................ 6 3.2 James Chadwick .............................................................................................................. 6 3.3 Enrico Fermi .................................................................................................................... 6 4 Nuclear Fission........................................................................................................................ 7 5 Nuclear Energy........................................................................................................................ 7 6 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................... 8 List of Figures Figure 1 Timeline of significant discoveries -

Absolute Zero, Absolute Temperature. Absolute Zero Is the Lowest

Contents Radioactivity: The First Puzzles................................................ 1 The “Uranic Rays” of Henri Becquerel .......................................... 1 The Discovery ............................................................... 2 Is It Really Phosphorescence? .............................................. 4 What Is the Nature of the Radiation?....................................... 5 A Limited Impact on Scientists and the Public ............................ 6 Why 1896? .................................................................. 7 Was Radioactivity Discovered by Chance? ................................ 7 Polonium and Radium............................................................. 9 Marya Skłodowska .......................................................... 9 Pierre Curie .................................................................. 10 Polonium and Radium: Pierre and Marie Curie Invent Radiochemistry.. 11 Enigmas...................................................................... 14 Emanation from Thorium ......................................................... 17 Ernest Rutherford ........................................................... 17 Rutherford Studies Radioactivity: ˛-and ˇ-Rays.......................... 18 ˇ-Rays Are Electrons ....................................................... 19 Rutherford in Montreal: The Radiation of Thorium, the Exponential Decrease........................................... 19 “Induced” and “Excited” Radioactivity .................................... 20 Elster -

Character List

Character List - Bomb Use this chart to help you keep track of the hundreds of names of physicists, freedom fighters, government officials, and others involved in the making of the atomic bomb. Scientists Political/Military Leaders Spies Robert Oppenheimer - Winston Churchill -- Prime Klaus Fuchs - physicist in designed atomic bomb. He was Minister of England Manhattan Project who gave accused of spying. secrets to Russia Franklin D. Roosevelt -- Albert Einstein - convinced President of the United States Harry Gold - spy and Courier U.S. government that they for Russia KGB. Narrator of the needed to research fission. Harry Truman -- President of story the United States Enrico Fermi - created first Ruth Werner - Russian spy chain reaction Joseph Stalin -- dictator of the Tell Hall -- physicist in Soviet Union Igor Korchatov -- Russian Manhattan Project who gave physicist in charge of designing Adolf Hitler -- dictator of secrets to Russia bomb Germany Haakon Chevalier - friend who Werner Reisenberg -- Leslie Groves -- Military approached Oppenheimer about German physicist in charge of leader of the Manhattan Project spying for Russia. He was designing bomb watched by the FBI, but he was not charged. Otto Hahn -- German physicist who discovered fission Other scientists involved in the Manhattan Project: Aage Niels Bohr George Kistiakowsky Joseph W. Kennedy Richard Feynman Arthur C. Wahl Frank Oppenheimer Joseph Rotblat Robert Bacher Arthur H. Compton Hans Bethe Karl T. Compton Robert Serber Charles Critchfield Harold Agnew Kenneth Bainbridge Robert Wilson Charles Thomas Harold Urey Leo James Rainwater Rudolf Pelerls Crawford Greenewalt Harold DeWolf Smyth Leo Szilard Samuel K. Allison Cyril S. Smith Herbert L. Anderson Luis Alvarez Samuel Goudsmit Edward Norris Isidor I. -

Commentary & Notes Hans Bethe

J. Natn.Sci.Foundation Sri Lanka 2005 33(1): 57-58 COMMENTARY & NOTES HANS BETHE (1906-2005) Hans Albrecht Bethe who died on 6 March 2005 within the sun is hydrogen which is available in at the age of 98, was one of the most influential tremendous volume. Near the centre of the sun, and innovative theoretical physicists of our time. hydrogen nuclei can be squeezed under enormous pressure to become the element helium. If the Bethe was born in Strasbourg, Alsace- mass of hydrogen nucleus can be written as 1, Lorraine (then part of Germany) on 2 July 1906. Bethe showed that each time four nuclei of His father was a University physiologist and his hydrogen fused together as helium, their sum was mother Jewish, the daughter of a Strasbourg not equal to 4. The helium nucleus weighs about professor of Medicine. Bethe moved to Kiel and 0.7% less, or just 3.993 units of weight. It is this Frankfurt from where he went to Munich to carry missing 0.7% that comes out as a burst of explosive out research in theoretical physics under Arnold energy. The sun is so powerful that it pumps 4 Sommerfeld, who was not only a great teacher, million tons of hydrogen into pure energy every but an inspiring research supervisor as well. second. Einstein's famous equation, E = mc2, Bethe received his doctorate in 1928, for the work provides a clue to the massive energy that reaches he did on electron diffraction. He then went to the earth from the sun, when 4 million tons of the Cavendish laboratory in Cambridge on a hydrogen are multiplied by the figure c2 (square Rockefeller Fellowship, and Rome, before of the speed of light). -

The Institute for Radium Research in Red Vienna

Trafficking Materials and Maria Rentetzi Gendered Experimental Practices Chapter 4 The Institute for Radium Research in Red Vienna As this work has now been organized after several years of tentative efforts each collaborator has his or her [emphasis mine] particular share to take in making the practical preparations necessary for an experiment. Besides each has his or her particular theme for research which he pursues and where he can count on the help from one or more of his fellow workers. Such help is freely given certain workers having spent months preparing the means required for another workers theme.1 When Hans Pettersson submitted this description of the work at the Radium 1 Institute in a report to the International Education Board in April 1928, several women physicists were already part of his research team on artificial disintegration. A number of other women explored radiophysics and radiochemistry as collaborators of the institute, formed their own research groups, and worked alongside some of the best-known male physicists in the field. More specifically, between 1919 and 1934, more than one-third of the institute's personnel were women. They were not technicians or members of the laboratory support stuff but experienced researchers or practicum students who published at the same rate as their male counterparts. Marelene Rayner-Canham and Geoffrey Rayner-Canham have already drawn our 2 attention to the fact that women clustered in radioactivity research in the early twentieth century. Identifying three different European research schools on radioactivity—the French, English, and Austro-German—the Rayner-Canhams argue that women "seemed to play a disproportionately large share in the research work in radioactivity compared to many other fields of physical science."2 Through prosopographical studies of important women in these three locations, the authors address the puzzle of why so many women were attracted to this particular field. -

Radioactivity Redux Marjorie C

Metascience DOI 10.1007/s11016-012-9697-7 SURVEY REVIEW Radioactivity redux Marjorie C. Malley: Radioactivity: A history of a mysterious science. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, xxi+267pp, $21.95 HB Lauren Redniss: Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie, a tale of love and fallout. New York: itbooks, HarperCollins Publishers, 2011, iv+205pp, $29.99 HB Naomi Pasachoff Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2012 As readers of Metascience probably know, just as 2005 was the International Year of Physics, commemorating the centennial of Einstein’s annus mirabilis, and 2009 was the International Year of Astronomy, commemorating the 400th anniversaries of Galileo’s telescope and of Kepler’s Astronomia Nova, 2011 was the International Year of Chemistry, commemorating the 100th anniversary of Marie Curie’s Nobel Prize for Chemistry, ‘‘in recognition of her services to the advancement of chemistry by the discovery of the elements, radium and polonium, by the isolation of radium and the study of the nature and compounds of this remarkable element.’’ In 1898, Curie coined the term radioactivity to describe the properties of radium and polonium and similar substances. Neither of the two books under consideration in this review calls attention to the IYC, but, because of their link to Curie, it is perfectly appropriate that they were both published in 2011. Each book garnered more than a measure of praise, with Malley’s selected by the editors at Amazon.com and the staff of the Christian Science Monitor as one of the ‘‘nine best books of August’’ 2011, and Redniss’s becoming a finalist for the 2011 National Book Award for nonfiction. -

History of the Development of Atomic Theory READINGS.Pdf

Collaborative Learning Activity – How is it we have come to understand the inner workings of the atom? You will be split between several Groups, dependent on class size. In each group you will be responsible for a specific volume of the material. As “experts” you must be able to teach your part of the information regarding the historical development of the present-day model of the atom to others in each group. You will create a timeline of historical figures and brief sketches of each model of the atom as it evolved into what science now understands regarding the atom. The biographical information presented is important, but your main focus should be on the scientific contributions and experimentation that have guided physicists to present day understanding of the nature of the atom. Home Groups 1-6 Select Experts A - F rotate between Home Groups, Experts stay put. Activity: Step one day one. As a group, identify and illustrate the historical developments relevant to the structure of the atom as it came to be known during the period assigned to your group. Devise a plan to present to various Home Groups the following day. We will explore and highlight key developments from the ancient Greeks till now. Step two – Preparation: Finalize any of your research and Expert Graphic Organizer for presenting to Home Groups. Step three day two. Selected experts will rotate around the room and present their findings. Complete Timeline and sketches of the various models. Step four - Preparation: Complete / finalize any notes you miss. https://www.slideshare.net/mrtangextrahelp/02-a-bohr-rutherford-diagrams-and-lewis-dot-diagrams 1 Group 1 - Group 1 - Group 1 - Group 1 - Group 1 - Group 1 Do atoms exist? One of the most remarkable features of atomic theory is that even today, after hundreds of years of research, no one has yet “seen” a single atom. -

APS Membership Boosted by Student Sign-Ups Physics Newsmakers of 2013

February 2014 • Vol. 23, No. 2 Profiles in Versatility: A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN PHYSICAL SOCIETY Olympics Special Edition WWW.APS.ORG/PUBLICATIONS/APSNEWS See Page 3 APS Membership Boosted by Student Sign-ups The American Physical Society up for a free year of student mem- Physics Newsmakers of 2013 hit a new membership record in bership in the Society. APS Membership 2011-2014 2013 with students making up the In addition, the Society added 50,578 50,600 bulk of the growth. After complet- nearly 100 new early-career mem- Total ing its annual count, the APS mem- bers after a change in policy that Members The Envelope Please . bership department announced that extended membership discounts for 49,950 By Michael Lucibella the Society had reached 50,578 early-career members from three 49,300 members, an increase of 925 over to five years. “The change to five- Each year, APS News looks back last year, following a general five- year eligibility in the early career 48,650 at the headlines around the world year trend. “When we were able to category definitely helped.” Lettieri to see which physics news stories get up over 50,000 again, that was said. “That’s where a lot of our fo- 48,000 grabbed the most attention. They’re good news. That keeps us moving cus is going to be now, with stu- stories that the wider public paid in the right direction,” said Trish dents and early-career members.” 15,747 attention to and news that made a 16,000 Total Lettieri, the director of APS Mem- Student big splash. -

Atomic-Scientists.Pdf

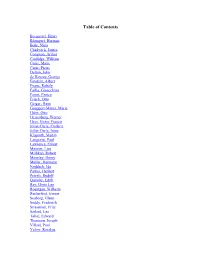

Table of Contents Becquerel, Henri Blumgart, Herman Bohr, Niels Chadwick, James Compton, Arthur Coolidge, William Curie, Marie Curie, Pierre Dalton, John de Hevesy, George Einstein, Albert Evans, Robely Failla, Gioacchino Fermi, Enrico Frisch, Otto Geiger, Hans Goeppert-Mayer, Maria Hahn, Otto Heisenberg, Werner Hess, Victor Francis Joliet-Curie, Frederic Joliet-Curie, Irene Klaproth, Martin Langevin, Paul Lawrence, Ernest Meitner, Lise Millikan, Robert Moseley, Henry Muller, Hermann Noddack, Ida Parker, Herbert Peierls, Rudolf Quimby, Edith Ray, Dixie Lee Roentgen, Wilhelm Rutherford, Ernest Seaborg, Glenn Soddy, Frederick Strassman, Fritz Szilard, Leo Teller, Edward Thomson, Joseph Villard, Paul Yalow, Rosalyn Antoine Henri Becquerel 1852 - 1908 French physicist who was an expert on fluorescence. He discovered the rays emitted from the uranium salts in pitchblende, called Becquerel rays, which led to the isolation of radium and to the beginning of modern nuclear physics. He shared the 1903 Nobel Prize for Physics with Pierre and Marie Curie for the discovery of radioactivity.1 Early Life Antoine Henri Becquerel was born in Paris, France on December 15, 1852.3 He was born into a family of scientists and scholars. His grandfather, Antoine Cesar Bequerel, invented an electrolytic method for extracting metals from their ores. His father, Alexander Edmond Becquerel, a Professor of Applied Physics, was known for his research on solar radiation and on phosphorescence.2, 3 Becquerel not only inherited their interest in science, but he also inherited the minerals and compounds studied by his father, which gave him a ready source of fluorescent materials in which to pursue his own investigations into the mysterious ways of Wilhelm Roentgen’s newly discovered phenomenon, X-rays.2 Henri received his formal, scientific education at Ecole Polytechnique in 1872 and attended the Ecole des Ponts at Chaussees from 1874-77 for his engineering training. -

The Beginning of the Nuclear Age

The Beginning of the Nuclear Age M. SHIFMAN 1 Theoretical Physics Institute, University of Minnesota 1 Introduction A few years ago I delivered a lecture course for pre-med freshmen students. It was a required calculus-based introductory course, with a huge class of nearly 200. The problem was that the majority of students had a limited exposure to physics, and, what was even worse, low interest in this subject. They had an impression that a physics course was a formal requirement and they would never need physics in their future lives. Besides, by the end of the week they were apparently tired. To remedy this problem I decided that each Friday I would break the standard succession of topics, and tell them of something physics-related but { simultaneously { entertaining. Three or four Friday lectures were devoted to why certain Hollywood movies contradict laws of Nature. After looking through fragments we discussed which particular laws were grossly violated and why. I remember that during one Friday lecture I captivated students with TV sci-fi miniseries on a catastrophic earthquake entitled 10.5, and then we talked about real-life earthquakes. Humans have been recording earthquakes for nearly 4,000 years. The deadliest one happened in China in 1556 A.D. On January 23 of that year, a powerful quake killed an estimated 830,000 people. By today's estimate its Richter scale magnitude was about 8.3. The strongest earthquake ever recorded was the 9.5-magnitude Valdivia earthquake in Chile which occurred in 1960. My remark that in passing from 9.5.