Delay in Verse Xi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

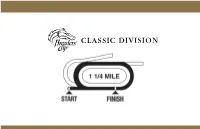

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

204 Longways Stables 204

204 Longways Stables 204 Empire Maker Pioneerof The Nile AMERICAN Star of Goshen PHAROAH Yankee Gentleman Littleprincessemma N. (USA) Exclusive Rosette Storm Cat chesnut filly 23/03/2018 Giant's Causeway ADESTE FIDELES Mariah's Storm 2011 (USA) Imagine Sadler's Wells 1998 Doff The Derby E.B.F./B.C. Nominated AMERICAN PHAROAH (2012), 9 wins at 2 and 3 years, Breeders' Cup Classic (Gr.1). Stud in 2016. Sire of FOUR WHEEL DRIVE, Breeders' Cup Juvenile Turf Sprint, Gr.2, SWEET MELANIA, Jessamine S., Gr.2, MAVEN, Prix du Bois, Gr.3, CAFE PHAROAH, Hyacinth S., L., HARVEY'S LIL GOIL, Busanda S., ANOTHER MIRACLE, Skidmore S., American Theorem, Monarch of Egypt. 1st dam ADESTE FIDELES, 1 win, pl. 3 times at 3 years in IRE. Own sister to VISCOUNT NELSON and POINT PIPER. Dam of : N., (see above), her 2nd foal. 2nd dam IMAGINE, 4 wins at 2 and 3 years in GB and IRE, Irish 1000 Guineas (Gr.1), Oaks S.(Gr.1), C. L. Weld Park S.(Gr.3), 2nd Rockfel S.(Gr.2), £382,032. Own sister to STRAWBERRY ROAN. Dam of 12 foals of racing age, 9 winners incl. : HORATIO NELSON (c., Danehill), 4 wins at 2 years in FR, IRE & GB, Prix Jean-Luc Lagardère (Gr.1), Futurity S.(Gr.2), Superlative S.(Gr.3), 2nd Dewhurst S.(Gr.1), £284,236. VISCOUNT NELSON (c., Giant's Causeway), 4 wins at 2 to 5 in IRE & UAE, Al Fahidi Fort S.(Gr.2), 2nd Champagne S.(Gr.2), 3rd Irish 2000 Guineas (Gr.1), Eclipse S.(Gr.1), £465,391. -

Minding the Gap : a Rhetorical History of the Achievement

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap Laura Elizabeth Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Laura Elizabeth, "Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3633. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3633 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MINDING THE GAP: A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Laura Jones B.S., University of Colorado, 1995 M.S., Louisiana State University, 2010 August 2013 To the students of Glen Oaks, Broadmoor, SciAcademy, McDonough 35, and Bard Early College High Schools in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana ii Acknowledgements I am happily indebted to more people than I can name, particularly members of the Baton Rouge and New Orleans communities, where countless students, parents, faculty members and school leaders have taught and inspired me since I arrived here in 2000. I am happy to call this complicated and deeply beautiful community my home. -

Minding the Body Interacting Socially Through Embodied Action

Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1112 Minding the Body Interacting socially through embodied action by Jessica Lindblom Department of Computer and Information Science Linköpings universitet SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2007 © Jessica Lindblom 2007 Cover designed by Christine Olsson ISBN 978-91-85831-48-7 ISSN 0345-7524 Printed by UniTryck, Linköping 2007 Abstract This dissertation clarifies the role and relevance of the body in social interaction and cognition from an embodied cognitive science perspective. Theories of embodied cognition have during the past two decades offered a radical shift in explanations of the human mind, from traditional computationalism which considers cognition in terms of internal symbolic representations and computational processes, to emphasizing the way cognition is shaped by the body and its sensorimotor interaction with the surrounding social and material world. This thesis develops a framework for the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition, which is based on an interdisciplinary approach that ranges historically in time and across different disciplines. It includes work in cognitive science, artificial intelligence, phenomenology, ethology, developmental psychology, neuroscience, social psychology, linguistics, communication, and gesture studies. The theoretical framework presents a thorough and integrated understanding that supports and explains the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition. It is argued that embodiment is the part and parcel of social interaction and cognition in the most general and specific ways, in which dynamically embodied actions themselves have meaning and agency. The framework is illustrated by empirical work that provides some detailed observational fieldwork on embodied actions captured in three different episodes of spontaneous social interaction in situ. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

Ancient Skiers Book 2014

Second Edition - 2014 INTRODUCTION When I was asked if I would write the history of the Ancient Skiers, I was excited and willing. My husband, Jim, and I were a part of those early skiers during those memorable times. We had “been there and done that” and it was time to put it down on paper for future generations to enjoy. Yes, we were a part of The Ancient Skiers and it is a privilege to be able to tell you about them and the way things were. Life was different - and it was good! I met Jim on my first ski trip on the Milwaukee Ski Train to the Ski Bowl in 1938. He sat across the aisle and had the Sunday funnies - I had the cupcakes - we made a bond and he taught me to ski. We were married the next year. Jim became Certified as a ski instructor at the second certification exam put on by the Pacific Northwest Ski Association (PNSA) in 1940, at the Ski Bowl. I took the exam the next year at Paradise in 1941, to become the first woman in the United States to become a Certified Ski Instructor. Skiing has been my life, from teaching students, running a ski school, training instructors, and most of all being the Executive Secretary for the Pacific Northwest Ski Instructors Association (PNSIA) for over 16 years. I ran their Symposiums for 26 years, giving me the opportunity to work with many fine skiers from different regions as well as ski areas. Jim and I helped organize the PNSIA and served on their board for nearly 30 years. -

Mirror Lake: Beauty & History Imagine Getting Paid for Your Hobby

Lynn Lotkowictz Lynn St. Petersburg, FL MAR/APR 2021 Est. September 2004 Imagine Getting Paid Changing Lives With for Your Hobby the Red Tent Initiative –– JANAN TALAFER –– ometimes a simple synchronicity can be life-changing in ways we couldn’t dream of at the time. That’s what happened Sfor Barbara Rhode, a St. Petersburg licensed marriage and family therapist and founder of the Red Tent Women’s Initiative. Barbara had just finished reading Anita Diamant’s book, The Red Tent – a compelling fiction about the ancient tradition of women seeking comfort in each other’s company while they spent time in the “red tent.” The book reinforced Barbara’s belief that for many women, having a safe space to share their feelings and experiences was very much missing in today’s society. John and Lien Satino with their dog Mino out for a drive in the vintage Edsel –– SAMANTHA BOND RICHMAN –– magine getting paid for your hobby. Shore Acres resident John Satino does just that. He’s a car guy from way back in his childhood, hanging out in his stepdad’s garage, and later fixing cars Ineeding a lot of work, which he bought from the ‘back lot’ of the local Chevy dealership and then sold for a profit. He was changing out engines and transmissions even before he had his driver’s license in his original state of Ohio. Since 1984, his car collection has been featured in numerous television and movie productions, sometimes generating a nice daily stipend, though clearly John would collect cars with or without the added attention. -

Verse WISCONSIN

issue 106 www.versewisconsin.org July 2011 Verse WISCONSIN Founded by linda Aschbrenner AS FREE VERSE 1998 “I think I became FEATURES funny by mistake.” MY BAREFOOT RANK BY DAVID GRAHAM —Denise Duhamel REVISING YOUR POEMS BY MICHAEL KRIESEL KARLA HUSTON INTERVIEWS “The truth is that oblivion DENISE DUHAMEL is not just commonplace for poets, but practically POETRY BY ERUM AHMED % IDELLA ANACKER % ANTLER % CHRISTOPHER AUSTIN % SUZANNE BERGEN % GERALD BERTSCH the rule. To harbor % AMY BILLONE %DAVID BLACKEY % JOHN L. CAMPBELL % ambitions for any other ANTONIA CLARK % CATHRYN COFELL % BARB CRANFORD % CX DILLHUNT % DENISE DUHAMEL % P.R. DYJAK % R. VIRGIL ELLIS fate is almost by definition % THOMAS J. ERICKSON % CASEY FRANCIS % JIM GIESE % SARA to be deluded.” GREENSLIT % JOHN GREY % KENNETH P. GURNEY % RICHARD HEDDERMAN % CHARLES HUGHES % CLINT JENSEN % HENK —David Graham JOUBERT % CLAIRE KEYES % JACKIE LANGETIEG % ESTELLA LAUTER % JOHN LEHMAN % QUINCY LEHR % DAVID LURIE % AMIT MAJMUDAR% JESSE MANSER % LINDA BACK MCKAY % RICK MCMONAGLE % MARY MERCIER % RICHARD MERELMAN % RICHARD MOYER % NORMAL % MAURICE OLIVER % HELEN PADWAY “In my brain’s basement, % NANCY PETULLA % CHARLES PORTOLANO % ESTER PRUDLO a reference librarian sits at % CASEY QUINN % CHRISTINE REDMAN-WALDEYER % JAMES REITTER % HARLAN RICHARDS % CHARLES RIES % MARYBETH a gray, metal, government RUA-LARSEN % CHUCK RYBAK % JANE SATTERFIELD % G. A. desk. When I’m writing, SCHEINOHA % JUDITH SEPSEY % JOHN SIME % KATE SONTAG % BARRY SPACKS % MARC SWAN % RICHARD SWANSON % TIMOTHY she hands me whatever old WALSH % MARIE SHEPPARD WILLIAMS % MARILYN WINDAU % image or line I need, when I need it. ” —Michael Kriesel $8 ? ? THANKS TO THESE DONORS! UP TO $100 Editors’ Notes ANTLER Writing is, at heart, a solitary act. -

CREATING BLUE OCEAN STRATEGY for AIR INDUS (PVT) Ltd

CREATING BLUE OCEAN STRATEGY FOR AIR INDUS (PVT) Ltd. CREATING... NOT COMPETING University of Management & Technology Creating Blue Ocean Strategy for Air Indus (PVT) Ltd. 2 PREFACE This project is done to accomplish the requirement for completion of my practicum for final semester of BS (Aviation Management) at University of Management & Technology. After screening out on ample of subject matters, I ultimately decided to go with topic "Creating a Blue Ocean Strategy for Air Indus (PVT) Ltd." as my study compels me to think that there is a strong need of incorporating Blue Ocean Strategy in Aviation industry in Pakistan. The topic was appreciated by my supervisor & I started to work on it with keen determination & hard work. I was bestowed with abundant of information through different sources that included reading & research material. Due to time constraints & mental & academic limitations, much is yet to be explored as I only did a small effort to put forward this maiden project done for aviation industry of Pakistan with respect to topic of Blue Ocean Strategy in airlines. I'm hopeful & positively looking forward for more contributions to this piece of work. I hope this incessant utilization of time & continuous efforts would turn into a continuous marathon of improvement until it reaches to summit of its perfect successions In sha Allah. Sobia Fayyaz ID: 12003001-030 Final Project, Bs Aviation Management, 2012-2016 Department of Aviation University of Management & Technology, Lahore. Dated 30 May, 2016 University of Management & Technology Creating Blue Ocean Strategy for Air Indus (PVT) Ltd. 3 Creating Blue Ocean Strategy for Air Indus (PVT) Ltd. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2012 Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics Joel P. MacClellan University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation MacClellan, Joel P., "Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1433 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Joel P. MacClellan entitled "Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Philosophy. John Nolt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jon Garthoff, David Reidy, Dan Simberloff Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) MINDING NATURE: A DEFENSE OF A SENTIOCENTRIC APPROACH TO ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Joel Patrick MacClellan August 2012 ii The sedge is wither’d from the lake, And no birds sing. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour.