The Suicide Battalion and Canada's Role in World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps During the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-09-13 Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, 'War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War Chase, Jordan A.S. Chase, J. A. (2013). Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, 'War Weariness' in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28595 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/951 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Unwilling to Continue, Ordered to Advance: An Examination of the Contributing Factors Toward, and Manifestations of, ‘War Weariness’ in the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Campaign of the First World War by Jordan A.S. Chase A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2013 © Jordan A.S. Chase 2013 Abstract This thesis examines the contributing factors and manifestations of ‘war weariness’ in the Canadian Corps during the final months of the Great War. -

The British Empire on the Western Front: a Transnational Study of the 62Nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4Th Division

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-09-24 The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division Jackson, Geoffrey Jackson, G. (2013). The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28020 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1036 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division By Geoffrey Jackson A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CENTRE FOR MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER 2013 © Geoffrey Jackson 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a detailed transnational comparative analysis focusing on two military units representing notably different societies, though ones steeped in similar military and cultural traditions. This project compared and contrasted training, leadership and battlefield performance of a division from each of the British and Canadian Expeditionary Forces during the First World War. -

Eyewitness Stories of the Avion Raid

EYEWITNESS STORIES OF THE AVION RAID Jul 1936 No. 23 THE FOURTY NINER THE ADVERTISERS MAKE OUR MAGAZINE A POSSIBILITY. THEY DESERVE OUR BEST SUPPORT. Page 2 of 40 Jul 1936 No. 23 THE FOURTY NINER THE FORTY NINER - STAFF PRESIDENT: Major General, the Hon. W. A. Griesbach, C.B., C.M.G. D.S.O., K.C. EDITOR: Geo. D. Hunt. ASSISTANT EDITOR: Norman Arnold. BUSINESS MANAGER : Neville H. Jones. ADVERTISING MANAGER : Geo. E. Gleave. SUBSCRIPTIONS : 50 cents per year to cover two half yearly issues, payable in advance. A limited number of back copies are available upon application to N. Arnold, 11908 92nd street, Edmonton. Price 10c per copy. ADVERTISING RATES; May be had upon application to George E. Gleave, Post Office Building, Edmonton. Subscribers are particularly requested to notify N. Arnold of any change of address. All communications including those relating to subscriptions or advertising should be addressed to the responsible officials as indicated above. THE ADVERTISERS MAKE OUR MAGAZINE A POSSIBILITY. THEY DESERVE OUR BEST SUPPORT. Page 3 of 40 Jul 1936 No. 23 THE FOURTY NINER Table of Contents THE FORTY NINER - STAFF ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 EDITORIAL - SANCTIONS ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 THE PASSING OF KING GEORGE V. ......................................................................................................................................... -

Saskatoon's War Memorial

Hidden Histories SASKATOON’S GREAT WAR MEMORIALS A Collaborative Project between the City of Saskatoon and By Eric Story the University of Saskatchewan Community Engaged-History Collaboratorium UofS Faculty Supervisor – Dr. Keith Carlson City of Saskatoon Supervisor – Kevin Kitchen “Hidden Histories” tells the stories of these pieces of art, yet it also speaks to Saskatoon’s collective story. Although these memorials remain rooted in one specific place in the city, the stories behind these memorials are not. As the memorials grow older, new generations tell new stories about them, some based in fact, others in myth. Like tales passed from an aging grandfather to Top of the Hugh Cairns Memorial Photo by Eric Story his grandson, they change INTRODUCTION “Hidden Histories . as they are passed along, speaks of Saskatoon’s shaped by the generations story.” who inherit these stories. And so here is my chance ave you ever walked toon enlisted, 5,602 men signed to tell our generation’s story down the street and up in the city, many travelling from about the memorials. I have Hwondered, “What is neighbouring communities to ac- tried to give voice to the that statue for?” or “Why is quire a uniform and fight for king individual, and less to the that there?”? This magazine, and country. stones that commemorate them. I hope I have done “Hidden Histories: Saska- By the time the Armistice was them justice. toon’s Great War Memori- declared on 11 November 1918, als,” provides answers to a Saskatoon had undergone a pro- few of these questions. found transformation. -

Canada's Victoria Cross

Canada’s Victoria Cross Governor General Gouverneur général of Canada du Canada Pro Valore: Canada’s Victoria Cross 1 For more information, contact: The Chancellery of Honours Office of the Secretary to the Governor General Rideau Hall 1 Sussex Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0A1 www.gg.ca 1-800-465-6890 Directorate of Honours and Recognition National Defence Headquarters 101 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0K2 www.forces.gc.ca 1-877-741-8332 Art Direction ADM(PA) DPAPS CS08-0032 Introduction At first glance, the Victoria Cross does not appear to be an impressive decoration. Uniformly dark brown in colour, matte in finish, with a plain crimson ribbon, it pales in comparison to more colourful honours or awards in the British or Canadian Honours Systems. Yet, to reach such a conclusion would be unfortunate. Part of the esteem—even reverence—with which the Victoria Cross is held is due to its simplicity and the idea that a supreme, often fatal, act of gallantry does not require a complicated or flamboyant insignia. A simple, strong and understated design pays greater tribute. More than 1 300 Victoria Crosses have been awarded to the sailors, soldiers and airmen of British Imperial and, later, Commonwealth nations, contributing significantly to the military heritage of these countries. In truth, the impact of the award has an even greater reach given that some of the recipients were sons of other nations who enlisted with a country in the British Empire or Commonwealth and performed an act of conspicuous Pro Valore: Canada’s Victoria Cross 5 bravery. -

Teaching Guide Table of Contents

THE ROYAL CANADIAN LEGION TEACHING GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 DEFINED BY MILITARY HISTORY 3 ARMED FORCES BEFORE 1914 4 ARMED FORCES OF THE FIRST AND SECOND WORLD WARS 6 ARMED FORCES OF THE KOREAN WAR 10 CANADA AND THE GULF WAR 12 PEACEKEEPING 13 THE COLD WAR 15 AFGHANISTAN 17 ON THE HOME FRONT 19 STATISTICALLY SPEAKING 21 SIGNIFICANT Dates IN Canada’S Military History 22 THE ROYAL CANADIAN LEGION 23 CANADA AND THE VICTORIA CROSS 26 SYMBOLS OF COMMEMORATION 27 THE Poppy CAMPAIGN 31 Poppy FUND Q&A 34 STORIES, SONGS AND POEMS 35 SCHOOL ACTIVITIES 42 NATIONAL LITERARY AND POSTER CONTESTS 47 Royal CANADIAN Legion’S PILGRIMAGE OF Remembrance 50 THE LEGION IS HERE TO HELP 51 WEBSITES OF INTEREST 52 PHOTO CREDITS 53 OTHER RESOURCES D-DAY POSTER 100TH ANNIVersary NAVY poster CANADA AND THE VICTORIA CROSS POSTER (PART 1) CANADA AND THE VICTORIA CROSS POSTER (PART 2) THE ROYAL CANADIAN LEGION • TEACHING GUIDE 1 introduction This Guide to Remembrance has been created by The In addition to the information available in the guide, Royal Canadian Legion to assist primary and secondary your local branch of The Royal Canadian Legion school teachers to foster the Tradition of Remembrance can be of much assistance. There are members at the Tamongst Canada’s youth. branch who would be more than willing to share their time and experiences. It is not the intention that Remembrance be a daily practice, but there is a need to ensure that today’s The Legion’s Web Site is www.Legion.ca which youth have a fundamental understanding of what their provides Remembrance material, amplifies Legion great-grandparents, grandparents and in some cases activities, contains a Branch Locator and links to their fathers and mothers were called upon to do to other sites presenting both Remembrance and defend the freedom and democracy that we enjoy general information. -

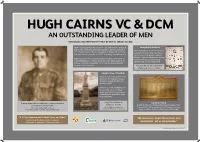

An Outstanding Leader of Men Researched and Written by Pupils of Bothal Middle School

HUGH CAIRNS VC & DCM AN OUTSTANDING LEADER OF MEN RESEARCHED AND WRITTEN BY PUPILS OF BOTHAL MIDDLE SCHOOL Hugh Cairns was born in Ashington on 4 December 1896. He went to Inseparable brothers Bothal School before his family emigrated to Saskatoon, Canada in Hugh and Albert Cairns were described as 1911. Hugh and two of his brothers (Albert & Henry) enlisted in the inseparable brothers. Albert was killed on Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1915. Only Henry survived the war. 10 September 1918 during the battle of Cambrai. Hugh was determined to avenge Hugh was sent to France and was awarded both the Victoria Cross his brother’s death and this may help and Distinguished Conduct Medal, Britain’s two highest awards for explain his heroics in November 1918. bravery. He died on 2 November 1918 from the wounds received winning his Victoria Cross. Hugh Cairns Memorial, Christ Church Anglican, Saskatoon. Photo QC-1677-3 courtesy of Saskatoon Public Library - Local History. Hugh’s love of football Hugh was a keen footballer and his team won the Saskatoon League Championship shortly before he enlisted in 1915. The Saskatoon Football Memorial is topped by a statue of Hugh Cairns and lists the 75 Saskatoon footballers who were killed in the First World War. Corporal Hugh Cairns shortly before he was promoted to Hugh Cairns Memorial, Lasting legacy Sergeant on 15 August 1918. Saskatoon, Canada Bothal Middle School memorial plaque, unveiled in 1921. Photo PH-HBS-27-2 courtesy of Photo CWM 19940079-023 courtesy of Dedicated to 128 former Bothal School pupils, including Saskatoon Public Library - Local History. -

Canada's Last Hundred Days in the First World War

Canada's Last Hundred Days, In The First World War. - Canada at War F... http://www.canadaatwar.ca/forums/showthread.php?t=2695 Canada at War Forums > Canada and First World War (World War I) > Battles > Canada's 100 Days User Name Remember Me? Canada's Last Hundred Days, In The First World War. Password Register FAQ Donate Members List Calendar Today's Posts Search Thread Tools Display Modes 05-21-2011, 10:35 PM Spaniard Canada's Last Hundred Days, In The First World War. The Lady From Hell! Quote: Join Date: Jan 2010 Posts: 864 Canada’s Hundred Days was a series of attacks made along the Western Front by the Canadian Corps during the Hundred Days Offensive of World War I. Reference to this period as Canada's Hundred Days is due to the substantial role the Canadian Corps of the British First Army played in causing the retreat of the German Army in a series of major battles from Amiens to Mons which along with other Allied offensives ultimately led to Germany's final defeat and surrender. Though generally referred to as the 'Hundred Days' in the English-speaking world outside of Canada, the period is more frequently recognized in Belgium and France - particularly in the areas in which the Canadians fought - as "les cent jours du Canada." During this time, the Canadian Corps fought at Amiens, Arras, the Hindenburg Line, the Canal du Nord, Bourlon Wood, Cambrai, Denain, Valenciennes and finally at Mons, on the final day of the First World War. Canadians entering the Square in Cambrai. -

Chronicles of Courage –

Chronicles of Courage Canada’s Victoria Cross Winners Compiled by Michael Braham Capt (N) (Ret’d) Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Origin of the Victoria Cross .......................................................................................................................... 6 Victoria Cross Facts ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Unusual Victoria Crosses ............................................................................................................................. 13 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Lieutenant Wallace Lloyd Algie, VC ......................................................................................................... 16 Major William George Barker, VC, MC**, DSO* ................................................................................ 18 Corporal Colin Fraser Barron, VC ............................................................................................................. 24 Lieutenant Edward Donald Bellew, VC .................................................................................................. -

Canada Made Great Contributions and Sacrifices in the First World War

real attack. On August 8, Canada led the way in with other successes along the British front, the this period and one who earned his VC in the final effort to restore peace and freedom are not an offensive that saw them advance 20 kilometres Hindenburg Line was now breached. two weeks of the war—serve as examples of the forgotten. in three days. This offensive was launched without kind of courage that many showed. a long preliminary artillery bombardment as was The German army may have been retreating but Legacy usually done (which also warned the enemy that that did not mean they stopped resisting. After On August 8, during the first day of the Battle of After more than four years of fighting, the war an attack was coming) and the Germans were further heavy fighting, Canadians helped capture Amiens, Lieutenant Jean Brillant of the was finally over. Many of Canada’s soldiers would taken totally by surprise. This breakthrough was a the town of Cambrai and by October 11 the Corps 22e Bataillon attacked and took an enemy machine serve as part of an occupation force in Germany, remarkable development and dashed enemy morale, had reached the Canal de la Sensée. This was the gun post, despite being wounded. He then led however, before finally being sent home in with the German high commander calling it “the last action taken by the Corps as a whole but the another attack that captured 15 German machine 1919. Canada’s accomplishments had earned it black day of the German Army.” individual Canadian divisions continued to fight, guns and took 150 prisoners. -

CEF Study Group Recommended Great War Websites

CEF Study Group Recommended Great War Websites - 11 November 2012 - Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group – Recommended Great War Websites – November 2012 he Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group (CEF Study Group) is an internet discussion forum dedicated to the study, exchange of information and discussion related to the Canadian T Expeditionary Force (CEF) in the Great War. The CEF Study Group forum was formed in 2004 by Neil Burns, Forum Administrator and was generally based around some of the original "Canadian Pals" from the Great War Discussion forum. In general, you will not find many websites which glorify war and conflict - the common theme is generally to accurately document this event and to provide for the remembrance of those who participated in this historic world conflict. All aspects of the Canadian Expeditionary Force is open to examination. The moderators, in alphabetical order are: Peter Broznitsky, Richard Laughton & Dwight Mercer (aka Borden Battery). Emphasis is on coordinated study, information exchange, constructive critiquing of postings and general mutual support in the research and study of the CEF. Membership is free (but donations gratefully accepted) and backgrounds range from first-time readers of history to doctoral researchers and published authors. The CEF Study Group discussion forum also has a number of members who volunteer as "Mentors" to assist new members on the discussion forum and as they start their own personal research. The objective of the CEF Study Group List of Recommended Great War Websites is to serve as a directory for the researcher. These websites have been researched and grouped into logical sections.